|

|

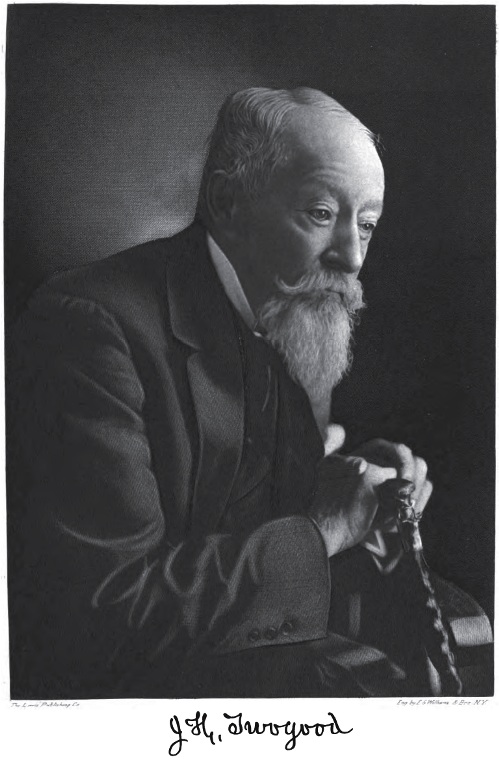

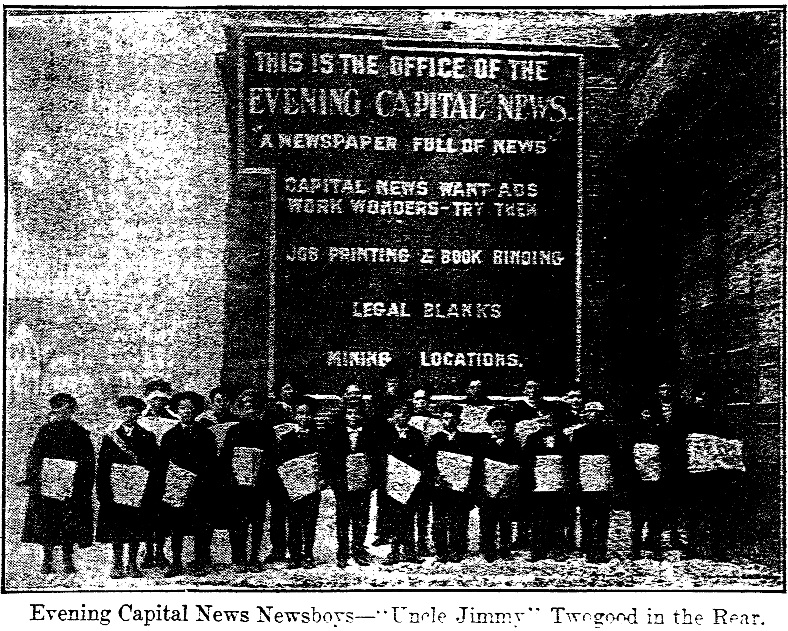

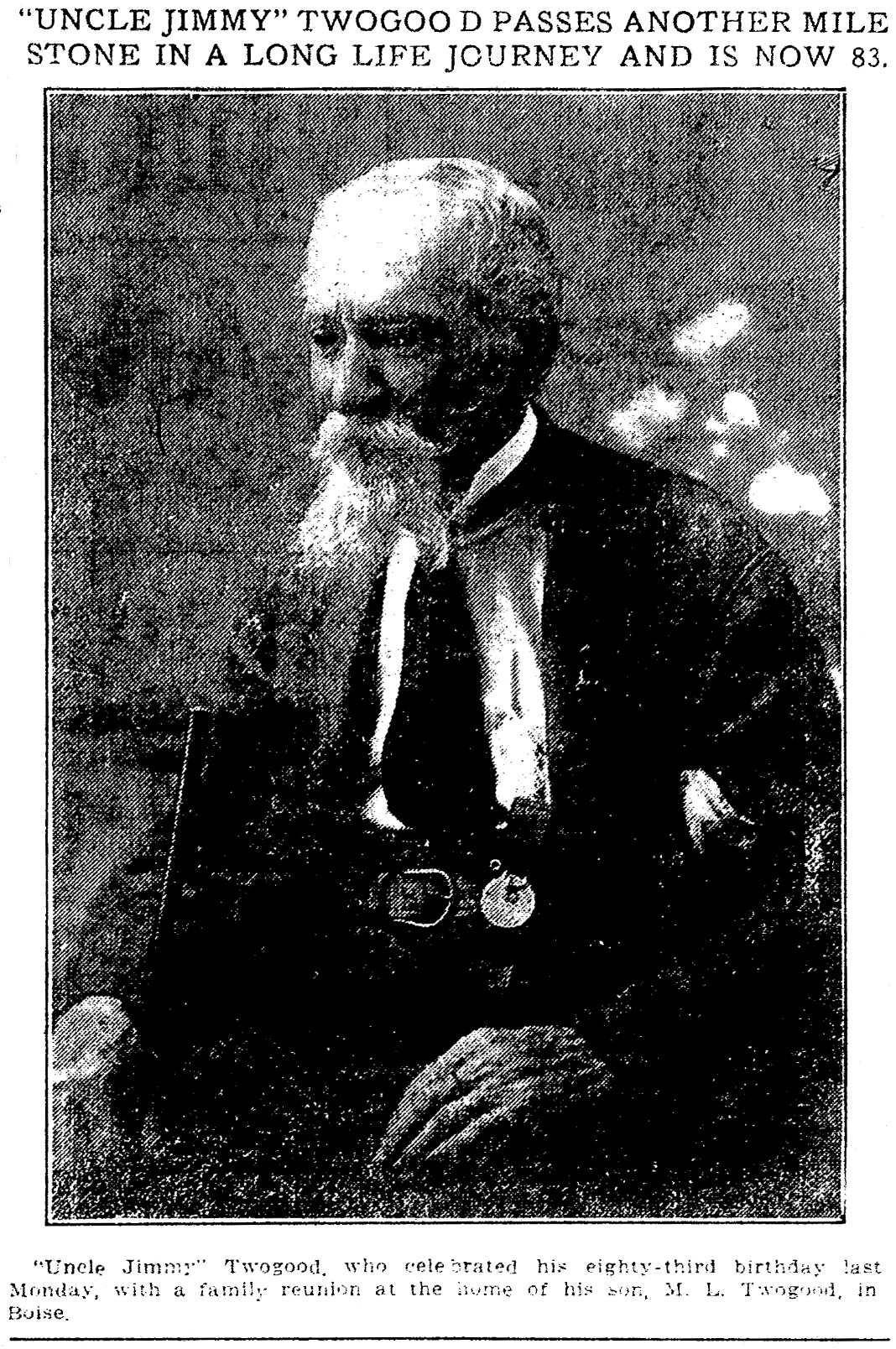

Jimmy Twogood and the Brand of Cain Extracts relating to his years in Southern Oregon, 1851-circa 1865, from James Henry Twogood's writings. In vaguely chronological order of events:  James H. Twogood, known to hundreds of admiring citizens of Boise and elsewhere as "Uncle Jimmy Twogood," was a native of New York, born near Troy, July 12, 1826. The eight children of William Twogood and wife are named as follows: Orestes B., who was a soldier in the First Wisconsin Infantry, became captain of his company, and after the battle of Stone River, where he had suffered much from exposure, was taken sick and died at his home, December 17, 1863; Helen, who died in infancy; Emily, who is still living and the wife of the late Merritt L. Satterlee, of Chicago; James H.; Elizabeth, still living, wife of the late [Stoughton] P. Jones of Jacksonville, Oregon; Sarah, also living, the wife of the late Colonel Alfred Chapin of Rockford, Illinois, Colonel Chapin having been a prominent soldier of the Civil War; Belle, who is the wife of the late J. F. Hervey, of Chicago; and William L., now of Los Angeles. The late James H. Twogood was eleven years of age when the family came west to Illinois, and with the exception of such education as he obtained in the primitive district schools of his locality he was chiefly educated in the city of Chicago during the five years' residence of his parents in that city. He also learned the harness maker's trade there and followed that as an occupation for a number of years. During the middle forties he was a member of the volunteer fire department of Chicago, and was active and well known in the citizenship of Chicago when the population comprised only a few thousand people. He was a young man of twenty-four when the lure of the West seized him and he came out into the then little known regions of Oregon. His introduction to this country may be described in his own words, as follows: "A younger brother and I crossed the plains in 1851 with a good four-horse rig of our own, landing in Oregon City August 20, but in trying to assist some of our more unfortunate friends, lost wagon, harness, all our clothing and a kit of saddler's tools. This changed the whole course of my life; could not go to work at my trade as I expected to do, so went to the mines in Southern Oregon." In the records of the War Department at Washington might be found a detailed account of his many adventures, hairbreadth escapes and losses incident to the Oregon Indian wars that devastated that country up to 1855. That phase of his life, however interesting in itself, must be only alluded to here. He was an enlisted volunteer, and took an active part in some of the fierce battles in which the Indians were put to rout, and after which they gave the early settlers but little trouble. He was a prospector and settler in the Grave Creek region of Oregon, and the Grave Creek Indians were considered the most hostile tribe in the entire country, and a large part of the war centered over that section. Shortly after the close of the Indian wars, Mr. Twogood returned to Rockford, Illinois, where he remained a few years. He then came again to the West and in 1870 located in Boise, from that time forward making this city his home. He saw Boise grow from a village of a few hundred people to the city of its present proportions. He took great pride in Boise, and this civic pride increased with his declining years. The late Mr. Twogood married Miss Permelia Custer of Pennsylvania. Mrs. Twogood died on January 2, 1911, and it was this break in their long and happy companionship which hastened the decline of Mr. Twogood. The two surviving children of their marriage are Merritt L. Twogood, and Mrs. Robert Loring, of Boise, formerly Miss Carrie T. Twogood. Excerpted from Hiram T. French, History of Idaho: A Narrative Account of Its Historical Progress, 1914, page 770. A TALE OF OLD TIMES

We got tired of hauling the best of the winter wheat to Chicago, 80

miles away, and exchanging it for groceries at 50 cents per bushel. We

only had coffee then on Sunday mornings. Good farm hands received $12 a

month, although I have worked for as low as $8. In May, 1842, I rented

a ranch on shares and moved back to Chicago.Being a Reminiscent Article by James H. Twogood Formerly of Jacksonville. (By James H. Twogood.) The Chicago Daily Journal was established in 1844. At that time it was the leading journal of the state. Dick and Charley Wilson were the proprietors in 1848. I became acquainted with Charley, who was several years the younger. At that time he was a very diffident, bashful young man, and so awkward in company that he did not know how to hold his hands. I persuaded him to attend J. B. Robinson's balls, which were given at the City Hall, a brick building located in the middle of State Street, between Lake and Randolph. The lower floor was rented for market and the upper floor at the south end was used by the city council. The north end was used as a big dance hall. The music was furnished by Putnam's quadrille orchestra. In 1883-84 Robinson ran a theater in Boise where the capitol building now stands. Well, after a good deal of persuasion I finally succeeded in getting Wilson to attend Robinson's balls. It did not take long to "thaw'' him out and to get that refrigerator expression off his face, and it soon got out so that he could speak to a real live woman! It was in November 1841 that I drove a team to the ratification of William Henry Harrison's log cabin convention at Rockford, Ill. The war with Mexico commenced to brew in 1849 but there was nothing doing but "growl'' until Zachary Taylor got to the Rio Grande, opposite Matamoros, March 28, 1846. In April, 1847, I enlisted with four other boys from our shop. Mother said, "No!'' Two of the boys returned in 1850, and I was always sorry that I did not go, and then from there on to California. Today I might have been a rich man or perhaps lying six feet under ground--you can't generally sometimes tell! After Zachary Taylor established his dental parlors in Old Mexico it did not take him long to extract all the venomous teeth in sight. With that job done he thought he would take a run up north and see if all the folks were "to home.'' He found them and got himself in trouble--they made him President. Taylor beat both Cass and Van Buren, and of course his election had to be celebrated in due style. Dick Wilson had succeeded in getting a young cannon [i.e., a small cannon] and dragged it out on the public square, which was bounded by Clark, Washington, LaSalle and Rudolph streets. Wilson got very much excited. He was making that gun pop for all there was in it and more, too, and it rattled like a Gatling gun. I remember he had off his hat, coat and vest and his face was begrimed with sweat and powder. He was perfectly frantic, just as though the existence of the nation depended on that gun. In his excitement the perspiration was oozing out of every pore and running into his eyes so that he could hardly see. He seemed to entirely lose sight of the fact that the gun was getting hotter and needed swabbing out. It took four persons to work this cannon after it was unlimbered--the powder boy passed the "noise,'' Wilson rammed it home, the man behind the gun primed and when the man with the long slim rod--red on one end--brought it into requisition, there was something doing. At this juncture Mr. Wilson rammed a cartridge home and there was an explosion immediately. The ramrod went off, likewise one of Mr. Wilson's arms. Although standing within 30 feet I could not tell if the gun was touched off before giving Mr. Wilson time to withdraw the rod or if it was premature. I met Mr. Wilson many times after that on Lake Street carrying an empty sleeve. Mr. Wilson's heart and soul was in the work of being an old-line Whig. You seldom ever met a more nervy man than Dick. His last words were: "Keep her a-going boys,'' and he fell in a dead faint. It was a horrible sight and one that I will never forget. I would say to the old-timers that Zack Taylor's career was cut short. He was inaugurated March 4, 1849, and died July 9, 1850. William Henry Harrison served from March 4 to April 7, 1841. I called on Charley Wilson April 9, 1851. The next day my brother, O. B. and I started out west to find sunset and gold. I told Charley that I would let him hear from me en route, and the following is a copy of the first letter, which was reprinted in a home paper. Who of you readers can produce a clipping from a newspaper that you wrote nearly 57 years ago--more than the average man's lifetime? There are but few of the early timers of 1837 left in Chicago. The following is the clipping referred to, exactly as it appeared in the paper to which I sent it: Correspondence of the Chicago Journal. Iowa City, April 21st, 1851.

Friend Wilson:--We arrived safe in this great metropolis today en route

for Oregon. We came via Rockford and thence down Rock River on the east

side. We found good roads and as good a farming country as need be, all

the way down to its mouth. We crossed the Mississippi River at Rock

Island, and stopped at Davenport. It is quite a stirring little place

and built up mostly of brick, as is also Stevenson on the opposite side

of the river. There is more Germans here, according to the population,

than there is in Chicago. Moline is a very flourishing little town,

situated three miles above Rock Island. It's quite a manufacturing

place. There were two men lodged in jail at Davenport, a few days

since, for passing counterfeit tens on the Wisconsin Fire and Marine

Insurance Co. They had passed some three hundred dollars. Corn is worth

25 cents per bushel; oats 30 cents, and wheat 50. We did not see any

good winter wheat until we got below Dixon on Rock River. There is a

little in this state but not very good. We have met with but one Oregon

team on the way, and that was an ox team in a miserable condition.

There is but few teams on the road and those are mostly cattle. We have

four good horses, a light wagon, and our baggage does not exceed ten

hundred. We have no difficulty in driving 30 or 40 miles per day. We

have been one week on the road and think in one more we will be able to

make the bluffs, although we have a good many rivers and small streams

to cross, but so far they all have good bridges or ferries. Cedar River

between here and Muscatine is two-thirds as large as Rock River, and

Iowa River at this place is about the same size. There is some 30 or 40

Californians encamped just below here, from Wisconsin. This being the

last point in the settlements, I shall not have another chance to write

until we reach the bluffs, when I will write you again.Yours &c., J.H.T.

Jacksonville Post, March 21, 1908, page 3HE FOUND SOME CHANGES.

But No Wonder; He Hadn't Seen Portland Since 1851.

Portland

has changed considerably in 49 years, according to J. H. Twogood, a

retired mining man of Boise, Idaho, who is here attending the carnival.

He had not visited Portland since he left here in 1851, and could

locate none of the landmarks he expected to find. "Portland was only a

slab town then," he said yesterday, "and the schooners used to dump

their goods on the river bank, to be taken to Oregon City later on by

tug. Oregon City was the place then. But what a change! It seems like

awakening from a 50-year sleep, to find myself in a giant metropolis,

where at that time the woods were too dense for even a man to walk

through."

Mr. Twogood left Chicago April 10, 1851, and traveled as far as Elgin on the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad, the only line out of Chicago. At Elgin he boarded Frink & Walker's stage to Rockford, where he met a brother-in-law with a four-horse team, and it took 30 days more to drive to the Missouri River crossing. After a toilsome journey he reached Oregon City, August 20. O. B. Twogood, the brother, started a hardware business at Oregon City, but returned to the States via the Isthmus of Panama in 1857. J. H. Twogood afterward located the Grave Creek ranch, which was on the route of a pack train between Oregon and California. When the Indian war broke out in Southern Oregon in 1855 this ranch became the headquarters for the Southern Battalion, and was known as Fort Leland. He says most of the participants in that war have joined the silent majority ere this. Mr. Twogood is still in good health and spirits, and is liable to see a good many years of the new century if he remains in the Northwest, where the mild climate and happy surroundings render getting old a slow process. Morning Oregonian, Portland, September 8, 1900, page 12 - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Twogood & Harkness ad, May 12, 1855 Umpqua Weekly Gazette The following is the clipping referred to, exactly as it appeared in the paper to which I sent it: Correspondence of

the Chicago Journal

From an Oregon-Bound Emigrant.

Iowa

City, April 21st, 1851.

Friend Wilson:--We arrived safe in this great metropolis today en route

for Oregon. We came via Rockford and thence down Rock River on the east

side. We found good roads and as good a farming country as need be, all

the way down to its mouth. We crossed the Mississippi at Rock Island,

and stopped at Davenport. It is quite a stirring little place and built

up mostly of brick, as is also Stevenson on the opposite side of the

river. We have met with but one Oregon team on the way, and that was an

ox team in a miserable condition. There is but few teams on the road,

and those are mostly cattle. We have four good horses, a light wagon,

and our baggage does not exceed ten hundred. We have no difficulty in

driving 30 or 40 miles per day. We have been one week on the road and

think in one more we will be able to make the bluffs, although we have

a good many rivers and small streams to cross, but so far they have all

been good bridges or ferries. There is some 30 or 40 Californians

encamped just below here, from Wisconsin. This being the last point on

the settlements, I shall not have another chance to write until we

reach the Bluffs, when I will write you again.

Yours &c.,

J. H.

T.

James H. Twogood,

"Tells of Early Days in Chicago," Evening Capital News, Boise,

Idaho,

March

7, 1908, page 16 The complete article was

reprinted in the Jacksonville Post, March 21,

1908, page 3

I crossed the plains in 1851 and landed at Portland, where there was a wharf and a dozen log cabins. I was entitled to a quarter section of land from the government, but there was nothing there. I could not wait, but Judge Denny, captain of our company, could, and a few years later located a half section, of what is now Seattle. J. H. Twogood, "First Ball Given by Fire Department of Boise in 1876," Evening Capital News, Boise, Idaho, February 25, 1908, page 8 From Cow Creek the road is dry, but mountainous and rugged, to Grave Creek, eight miles, which has a valley sufficient for one or two claims, and a log hut is erected, but not occupied at present. This creek has its name from the circumstance of a woman, from an emigrant company, having been buried here a few years ago. Its Indian name is Ah-pel-pah. Nathaniel Coe, "Umpqua and Rogue River Valleys," Oregonian, Portland, July 3, 1852, page 2 Extermination of the Grave Creek

Indians.

Messrs. Adams and McCormick, who arrived here a day or two since, give

us the following information relative to the Grave Creek Indians. They

state that two weeks last Wednesday [on August 17] four

Indians were got into Mr.

Bates' house, but as yet the women and three others had not come in.

The whites waited till the rest of the Indians came up. Mr. Owens was

there with a guard to protect the U.S. mail. When the other Indians

came in Mr. J. H. McCormick was ordered to take charge of the armed

white men, four in number, outside. It was ordered that no firing be

done till near enough to make sure shots. The chief and three others

were in Bates' house, in charge of Mr. Charles Adams. Mr. McCormick's

attack was to be the signal for Adams inside. When the outside signal

was given Adams shot a noted Indian named John. Mr. Thomas Frazelle

shot at the chief, wounding him. The chief sprang at him with a shovel,

aiming at his head, but was warded off, giving a dangerous wound in the

hand. The chief then gathered in and threw him, when Adams put two

balls through him and he expired. Capt. Owens came in, when an Indian

sprang upon and threw him. While down Mr. Adams put two balls through

him and he expired. In the melee Owens received two balls through his

hat.

The question then arose whether the squaws and children should be put to death. Through Messrs. Adams and McCormick's exertions they were unharmed. The only one left of the male race of this tribe is a young lad some eight or ten years old, a very bright and intelligent boy, whom they brought to this place with them. Oregon Weekly Times, Portland, September 10, 1853, page 2 Camping in Early and Latter Days.

EDITORS PRESS:--At the present time no doubt thousands on this coast

are planning for their annual trip to the mountains for a season of camp

or outdoor life; and just now it may not be out of place to review some

of the probable reasons that have led to this pleasant and healthful

mode of recreation. This brings vividly to my mind when on the evening

of March 15, 1852, the writer at the age of 22 boarded a passing

steamer at Madison, Ind., and sailed down the beautiful and placid Ohio,

and up the turbid Mississippi, and Missouri, to St. Joseph; there to

prepare and start on the long and perilous trip across the plains with

ox teams. One hundred and ten days were spent on this long and tedious

journey. My companion (Robt. Gordon) and the writer were provided with

a small tent, buffalo robe for bed, and blankets for covering. This was

our first experience in camp life, and up to this time failed to find

any pleasure in it.On reaching the then village of Portland, Oregon, we had another little experience in traveling 300 miles on foot to the new El Dorado that had just opened for the miner in Southern Oregon. As we traveled up the beautiful Willamette Valley, we enjoyed all the comforts of our eastern homes, but as we passed through the Umpqua Valley, the settlers were farther apart and we did not always find a house to stop at overnight, but would have to go supperless to bed on the bare ground with a stone for a pillow. I will mention here that we spent one night in the Umpqua Valley with Uncle Jesse Applegate, an old pioneer of Oregon who crossed the plains in '45 or '46. [It was 1843.] A Pioneer

Hostelry.

On reaching Grave Creek in the Rogue River country, we had our first

experience in a public inn of the miner type. It was built of round logs

about 10x12, one side of which was taken up with a counter made of

split boards, behind which a goodly stock of the ardent was kept and

dealt out at 25 cents a drink. On inquiry we were told that we could

have both meals and lodgings, but we failed to see where either was to

come from. Finally we discovered the kitchen under a spreading oak,

where bread was baked in a frying pan, and served with bacon, Chile

beans and coffee for 75 cts. a meal.We enjoyed our supper, but could not yet see where we could find rest for our weary limbs after a long day's march on foot; but when the hour arrived to retire for the night, we ventured to ask to be shown to our rooms, when the proprietor [A. S. Bates], who stood behind the counter, reached us a grizzly bear skin and a pair of blankets, and told us to make our beds right where we stood--on the ground (his hotel had no floor).… Outdoor Life.

It may be said we were now pretty well initiated

into the new order of things, but the next three years spent in the

mines, and in the war with the Rogue River Indians in 1853, and again in

1855, gave us a rougher experience yet. But perhaps enough has been

said to call to the minds of thousands of our old pioneers on this coast

a similar experience. One would suppose after such privations and

hardships one would be cured of all love for outdoor life, but such is

not the case. It has become, as it were, second nature with us, and as

often as the springtime comes around, so often we long for the

privilege of a tented season among the dells of our beautiful evergreen

mountains.John Mavity, Pacific Rural Press, San Francisco, May 17, 1884, page 490 Capt. Owen, with a company, succeeded in decoying five Indians into Bates' house, on Grave Creek, under the pretense of having a talk, and, after disarming and tying, shot them. This act, together with the killing of a defenseless Indian at the "rancherie" on Grave Creek, are believed to be all accomplished by that company during the war. "Affairs in the South," Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, September 27, 1853, page 2 Mongo, a half-breed, and Thos. Prewell, were killed and a third man wounded by the Indians near Long's ferry, on Rogue River, on Sunday last, while upon the same day the house of Mr. Raymond, near Jumpoff Joe, was burnt to the ground, consuming with it a great quantity of flour and groceries. Two other houses in the same neighborhood were also burnt. These outrages were in retaliation for the killing of seven Indians in the house of Mr. Bates, on Grave Creek. Letter from Camp Alden dated September 2, Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, September 27, 1853, page 2 At Grave Creek [in September 1853] I stopped to feed my horse and get something to eat. There was a house there, called the "Bates House," after the man who kept it. It was a rough wooden structure without a floor, and had an immense clapboard funnel at one end, which served as a chimney. There was no house or settlement within ten or twelve miles or more of it. There I found Captain J. K. Lamerick, in command of a company of volunteers. It seems he had been sent there by General Lane after the fight at Battle Creek, on account of the murder of some Indians there, of which he and others gave me the following account: Bates and some others had induced a small party of peaceable Indians, who belonged in that vicinity, to enter into an engagement to remain at peace with the whites during the war which was going on at some distance from them, and by way of ratification of this treaty, invited them to partake of a feast in an unoccupied log house just across the road from the "Bates House," and while they were partaking, unarmed, of this proffered hospitality, the door was suddenly fastened upon them, and they were deliberately shot down through the cracks between the logs by their treacherous hosts. Nearby, and probably a quarter of a mile this side of the creek, I was shown a large round hole into which the bodies of these murdered Indians had been unceremoniously tumbled. I did not see them, for they were covered with fresh earth. Doubtless this is the grave which Col. Nesmith saw as he came along some days later with his company on the way south, and which I think he mistook for the old grave of Miss Crowley. At least this is how these Indians came to their death. There was no fight there, or thereabout, with any Indians, and never had been. Fitzgerald and his dragoons were not there; and he did not even come to this country until the summer of 1855. About this same time, these same parties by some device captured an Indian chief and his boy, and agreed with the boy that if he would go into the mountains and hunt down an Indian chief who had refused to come in and treat with them, and bring in his head, they would liberate his father, otherwise they said they would kill him. The filial young savage, for his father's sake, undertook the task, and taking his rifle went alone upon the trail of the old chief, and in due time returned with his head a la Judith, which Bates hung by the hair to the roof-tree of his house, as an Indian trophy, where I saw it with my own eyes. But this was not all. Instead of liberating the captive, they killed both him and his son. Bates left the country soon after, and went, as I understood, to South America. The place passed into the hands of Mr. James Twogood, who afterward in partnership with Mr. Harkness made it a famous resting place for man and beast. Matthew P. Deady, Transactions of the Oregon Pioneer Association, 1883, "Southern Oregon Names and Events," pages 23 and 24  Grave Creek House Early Settlement of Southern

Oregon

In

the early 'fifties James H. Twogood kept a tavern or travelers' eating

and lodging house on Cow Creek, Jump-Off Joe, or somewhere on the

Oregon and California trail in Southern Oregon. His place and the one

at Dutchtown, now Aurora, near Oregon City, were considered the best

eating places between Portland and Sacramento. But "Jimmy" got tired of

running a hotel and went east more than 40 years ago and was living in

Illinois in 1868 when we attended the Republican National Convention at

Chicago. He was then lamenting because he had left "God's Country" for

cold, hot, too-wet and too-dry Illinois and had got so poor that he

could not go back to Oregon. We as a member of the Oregon delegation

got him a seat in the convention. Since then he has come back as far as

Idaho, where he now resides and has for some years. Some time ago he

sent some writings of his in the Boise

Evening News

of nearly a year ago, and also a communication concerning Southern

Oregon, to a friend in Eugene, Harry Huff, and requested that the

papers and the communication be handed to me, which has been done after

[a] long delay. But as the communication does not relate to recent news

and is historical we print it below as a contribution to early history:

I clip the above from the Medford, Oregon Tribune. Mr. Parker has written me since and wants to know if I know anything about Josephine Leland. My reply is, most emphatically, NO. And furthermore, there never was a person in existence by that name in Southern Oregon. Now, as I blazed the first tree for a settlement on Grave Creek in '51 and lived [there] until September '66, went through the Indian war there in 1853, another in 1855-6, I think I ought to know. And it's possible that I am the last one left of the '51 settlers. Crossed the plains after leaving Chicago, April 10, traveled days through Iowa without seeing a log cabin, got to Kanesville May 10, bought supplies, crossed the Missouri River, drove out 5 miles to camp, expecting to meet the Hadleys. They were gone. We started early next morning and drove 25 miles in 6 hours. My brother and I had [a] good rig. Wagon made by Peter Schutler, who belonged to my fire company [in Chicago. We had] two engines in 1845; here at Loop Fork [of the Platte River] we organized. Judge Denny, founder of Seattle, was made captain; H. G. Hadley and Aaron Rose, lieutenants, O. B. [Twogood], secretary. Thirty horse teams in train, no sickness in train of course; had to stand guard every night. Only one man shot by Indians, Mell Hadley, at Salmon Falls, Snake River. Bullet went in just below right nipple and came out close to his backbone. We laid by five days for him to die. Wouldn't die, so we took him through, landing at Oregon City, August 20. This was then the principal business center of Oregon Territory. Nothing at Portland but a wharf and a few log cabins. Brother and I lost everything by trying to help others through; wagon, harness, three years' clothing and my kit of harness tools, so I could not get a job. Sam Hadley and I rigged up with a tent and two months' provisions and started for mines that we heard of in Southern Oregon. We wended our way up through the Willamette Valley, which was very sparsely settled, via Salem, Albany, Marysville (now Corvallis) and up the Long Tom to Richardson's place; then to Eugene Skinner's place, where we found he had located section land, gift from Uncle Sam. Had log house and barn. Today it is Eugene. A few miles farther on we found where H. G. Hadley had located a half-section. We camped here three days; went to a log house, thence on over the [Calapooia] mountain, crossing the North Umpqua at Winchester. Five miles farther on we found Aaron Rose and family, our friends we left in Grand Ronde Valley. Ten miles farther on we found Jesse Roberts' place; thence on up to Myrtle Creek; crossed South Umpqua and up to north end of big canyon. Here we found Joseph Knott and family had located ranch in August. Then there was hardly a passable pack trail, worse than the Ohio Maumee Swamp we drove through in September 1836; 12 miles took two days. Knott's place was the last settlement. We got through [the] big canyon some way and camped down on Cow Creek; thence over mountains to Wolf Creek and over steep hills to Grave Creek. Here we nooned. Found beautiful little valley, good grass right beside the road, good mountain stream, pure water; this from the fact people dare not camp there for fear of Indians. We crossed over next divide and were in the Rogue River Valley. Crossing Jump-Off Joe and Louse Creek, [after] 20 miles we came to Ben Halstead's ferry, crossed and on down the south side of the Rogue River 7 miles. We found where James N. Vannoy, Jim Tuft & Co. had located a ferry. Tuft, in after years [a] banker at Grants Pass, now across the river, which reminds me that I must be the last one left of the old times of 1851. Traveling up Applegate, we crossed over into the Illinois Valley and up that stream until we came to Sam Fry's horse corral. This place must have been a little north of a place that was located in after years called Kerbyville. Here we met Hardy Elliff and Judge Mofford. The judge was killed here in Boise about 1864-5. It would seem there was a company of prospectors from Eureka [that] got over the Siskiyou Mountains some way in August 1851. We came by good places; went on west 40 miles and found gold in two creeks. Josephine Rollins was with the company. One they called Canyon and the other Josephine Creek. And this is where the Josephine corner [of the "Josephine Leland" name] is. Next morning we packed our two horses and led them over the mountain to Josephine. We found miners there who showed us a good place to camp among the fragrant firs. We unpacked our horses, put everything on them we did not want and turned them loose; of course they went back to camp. The horse is a very intelligent animal--next to man. And there are dogs that seem to possess almost human intelligence. Hadley and I pitched our tent on Josephine [Creek]; mined ten days, found we were not onto our job, got tired, sold our provender for $80 in gold dust and retraced our tracks via Vannoy's Ferry to [the] canyon. Here Hadley and I split the blanket, he taking the tent his wife made for us in Portland, going down the South Umpqua five or six miles below Myrtle Creek and took up a ranch. I stopped at Canyon, afterwards named [Canyon] Ville. Levy Knott had located a ranch at the south end of [the] canyon. I went to work for him and helped to build the first log cabin south of Canyon until you got to Rogue River. Halstead's and Vannoy's were the only cabins in Rogue River Valley at that time. We got the house up, and I hired out for cook at $50 per month. As a chef [I] was not much of a success, but could "bile" water without scorching it; also fry bacon and venison; make good salt-rising biscuit, bake it in [a] frying pan, make good coffee. No vegetables then except chili beans. $1 per meal. Travelers only too glad to get it, no kick coming; especially travelers that were out all day in heavy rain and wanted to get in the dry before a big blazing fire in a fireplace, 6 foot wide; get good toddy under their jacket of good old bourbon that had been shipped around the Horn, then packed 150 miles until it was well shook up and all the headache extracted. As everybody had to pack their blankets those days, we did not charge for lodging. After getting thawed out and imbibing of a few [decanters] of the elixir of life they would get congenial and tell of their trips in crossing the plains, the happiest days of their lives. In November Sam Huch (from Chicago) and I leased the house. It was here that I met Barney E. Simmons. Barney was a Yorker but moved to Michigan when a baby. He enlisted in 1897 for the Mexican War under Zack Taylor; went to California in '49 and drifted up into Oregon. Barney and I went out and located Grave Creek Ranch, and as I blazed the first tree for a settler and made it my home for 16 years I think, Mr. Parker, [I] am [a] pretty reliable authority about the first settlers, and would seriously object to having any monument there, as Josephine Leland, as Leland [i.e., Martha Leland Crowley] died before Josephine [Rollins] saw that country. The above statement, Mr. Parker, is in the main correct. But the hanging of 3 to 6 Indians on the limbs of the old oak tree is quite erroneous, as there never was a person hung on Grave Creek to my certain knowledge. J.

H. TWOGOOD.

P.S.

Josephine County was taken off Jackson County by act of

Legislature in the winter of 1854. Bill drawn up by Major Lupton, who

was shot by an Indian arrow at Table Rock, first outbreak of Indians

Sunday morning, Oct. 9, 1855. He lived but a few hours. Major Lupton's

bill not only created Josephine County, but changed the name of Grave

Creek to Leland, in honor of [Martha] Leland Crowley and Josephine for

Josephine Rollins, so you see Josephine Leland, as the

Johnny-came-latelies have it, would hardly go down with an old mossback.

Undated circa 1908 Oregon State Journal clipping, W. W. Fidler scrapbook, MS208 box 2 SOHS Early Days in Southern Oregon

By James H. Twogood

When

my brother, O.B., and I crossed the plains in 1851 there was no

settlement west of the Missouri River until we reached the great

Columbia River, where Dr. Whitman and family had started a mission to

try to civilize the treacherous red man, as early as 1836. We had a

rough trip over the Cascades, arriving in Oregon City August 20, 1851,

and losing everything we had trying to help others. At this time Oregon

City was the commercial center from whence all goods went south to the

Willamette and Umpqua valleys. Losing my tools, I could get no work,

and times were dull and money scarce. There was no Portland then, only

one paper. There was nothing doing anywhere in the Northwest.

We heard of real gold mines at Yreka and in Southern Oregon. Sam Hadley and I had a slight attack of the yellow fever. We rigged up a tent, and with two pack and two saddle horses started south to the new Eldorado. Traveling up the valley we found it very sparsely settled. Many sections of good land could be taken up by immigrants, lived on five years and it was a donation from our dear old Uncle Sam. In the valley we came to Eugene Skinner's place, where he had taken up a section of land. He had a log house and barn, and part of his yard was fenced, where he raised garden truck. Today Eugene is a big city with an opera house. We then traveled south over the the Calapooia Mountains, up the creek to the North Umpqua. Here we ferried to Winchester, which was then the county seat of Douglas County, a town of one log house. The county reached from the Siskiyou Mountains on the south to Calapooia on the north, 300 miles, and from the Pacific Ocean on the west to the Rocky Mountains on the east, enough territory to form 15 or 20 states like New "Jersey." Five miles farther south we found Deer Creek, likewise Aaron Rose and family, who were our traveling companions when we crossed the plains. Rose had located a half-section donation claim, which today is the present site of the town of Roseburg, the county seat of Douglas County, but the same territory is now carved up into a dozen counties. Traveling up the South Umpqua River 28 miles we came to the mouth of the big canyon, over a horrible road of 12 miles on the old immigrant trail. I do not see how it was possible for people to go over those roads with wagons. In 1852 I saw a man start over that road through the canyon with two yoke of oxen and a good wagon, and at the end of two days he got through with only the front wheels. Here we found Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Knott, who crossed the plains in 1850 from Ottumwa, Ia., and had located a ranch, built a log tavern, and called it Canyonville. They had three grown children, Levi, Jack and Libby, whom Vince Davis called "Sis." She married Bob Ladd, a very wealthy banker in Portland. The rest of them crossed the great divide years ago, and I am the only one left. After getting through the canyon we traveled down Cow Creek seven miles, then crossed over the mountains and on to Grave Creek, where we found a beautiful little valley with a gigantic oak tree and a grave right beside the road. Clover grew to the height of six inches, and it was an ideal camping ground. Did we camp there? I should say not. No one would dare to camp there on account of the Indians. It was considered the most dangerous point on the road. On south seven miles we crossed Jump-off Joe and Louse creeks and came to the Rogue River. Here we found Ben Halstead had established the first ferry on the trail between Oregon and California. We crossed here and went down seven miles and found James N. Vannoy, Jim Tuft & Co. had taken up a splendid ranch and put in a ferry. Both were as good men in principle as ever lived, and both are now dead. From here we traveled up the Applegate into the Illinois Valley, which we followed up to a point where Kerbyville now stands. We struck off north [sic] and found Sam Fry, who was running a horse corral. It seems as though a small company of California miners, during the month of August 1851, left Yreka and traveled north in search of gold. They traveled on the old Hudson Bay trapper trail over the Siskiyou, down Bear Creek, and right by Jackson Creek, where there were good diggings, and on to the Illinois Valley. Here they went north over pretty steep mountains and found gold in two different creeks. One they named Canyon Creek and the other Josephine, in honor of a young lady who was a member of the party. This was the first gold found in Oregon. Afterwards Sailor Diggings, Althouse and many other good diggings were struck. I was with the Joe Knott party in February 1852, and we were the first white men to ever make the trip up Galice Creek, where we found good diggings. Halstead and Vannoy had the only two log cabins in the Rogue River Valley in 1851. It seems to me like a fairy tale when I read about a fruit ranch being sold there for $168,000, and land near Medford producing $500 worth of fruit per acre. Early Settlement in Southern Oregon. It was in the fall of 1851 or early spring of 1852 that gold was first discovered in the Rogue River Valley. It was found on a little creek in paying quantities by a man named Jackson, who called it Jackson Creek, close to where Jacksonville, the seat of Jackson County, is located today. [Today the discovery of gold is credited to Clugage and Pool, following the directions of a man in the employ of Alonzo Skinner. The Jackson name was taken in honor of Andrew Jackson.] Sterling Creek was located by Mr. Sterling later. That proved rich and built up Jacksonville. In 1851 there was no sickness on the plains, but in 1852 there was a big immigration, and people died by the hundreds of cholera, all owing to the fact of their not taking the precaution of providing themselves with a bottle of Perry Davis' painkiller. In Chicago during the summer of 1849, when the epidemic was raging, there were 30 deaths in one day. I was taken with the cramps one day; I took a big jolt of Perry Davis' painkiller, laid down on a lounge and went to sleep and waked up in the evening feeling as frisky as a young colt. In the spring of 1852 a big immigration from the Willamette Valley went out to what is today called Josephine County. There was no county then, no sheriff or tax collectors, but a happy, happy people. The valley and villages settled up very rapidly, many coming up from around Portland and that section--Dave Birdseye, Colonel W. G. T'Vault, Captain Angel, the Millers and many whose names I have forgotten. C. C. Beekman is the only one left whom I know of from Yreka. My dear, good friend, a banker today, rode the first pony express from Yreka to Jacksonville. [Note that Beekman's express predated, and was unrelated to, the famous 1860-61 Pony Express that terminated in Sacramento.] It was about 1859 that another great mining excitement broke out, away up north in the Frazer River country. It fairly set people crazy. They flocked up there by thousands, by steamer from 'Frisco, and by the California and Oregon state route. The stages were loaded to the guards every trip. At Grave Creek house, a dinner station 40 miles north of Jacksonville, we used to cater to 10 or 12 passengers every day. Alex Rossi, a pioneer of Boise, came to California in the early days. He was a natural-born mechanic and good surveyor. He drifted north in 1853, crossing over the Siskiyou Mountains. At the foot of the mountain he found a town called Ashland. It was here, I think, that a Mr. Thomas, a big, jolly, 200-pound German, built the first flouring mill in Rogue River Valley. He was an old friend of John Krall, a well-known pioneer of Boise. Mr. Rossi went to work for Mr. Thomas and stayed until October 1, 1855. Then he again drifted north and came down to the Grave Creek house, stayed all night with us and started for Salem. In the meantime the Indians in the Rogue River Valley, under Chiefs Joe and Sam, had been committing depredations, robbing and killing white men. About October 8 the citizens of Jacksonville commenced to talk of the matter of retaliation. About October 8 they raised a company of volunteers and started for the Indian headquarters at Table Rock, near Fort Lane, which was established by General Joe Lane during the Indian war of 1853. This volunteer company was under command of my good friend Major Lupton. They attacked the Indians Sunday morning, October 9. Quite a number of the whites were wounded, and Major Lupton was shot through with an arrow that proved fatal. Hon. John Hailey, one of our most honored pioneers of this city [i.e., Boise, Idaho], helped extract the arrow. That fight gave the Indians a start, and the whole tribe came rushing down Rogue River, killing and burning everything before them. They caught me with a pack train down at Galice Creek, and I did not get home for three days, but that is another long story for the future. Suffice to say, this precipitated the biggest Indian war ever known on the Pacific coast, reaching from California on the south to British possessions on the north and where Idaho now stands on the east. When Mr. Rossi reached Salem we had a full-fledged Indian war on our hands. Here he met Governor George L. curry, who insisted upon mustering him into the service. As war had been declared, he was assigned to the quartermaster's department as clerk and remained in the office until the close of the war in June 1856, when all the Rogue River and Umpqua Indians were gathered up and transported to the Siletz Indian Reservation in the Willamette Valley, where they were placed under command of Lieutenant U.S. Grant. My thinker is getting decidedly defective, but I want to live long enough to write up the big Indian war of 1855-56 from its beginning on October 9, 1855 to its close in June 1856. It was the biggest war on the Pacific coast, and incidentally, about that time I had a thrilling ride for life. There were several hundred white men killed and wounded and quite a number of women. I guess I am the only one left who can write up his war from the southern part, as our place at that time was in the center, and was headquarters for the southern battalion and was known as Fort Leland. My thinker is beginning to desert me at the age of 84, but if the lamp holds out I will write up one more piece, "A Ride for Life," which I will illustrate with cuts of my penknife, as illustrations are a fad and no newspaper or magazine article is complete without them. It was in the summer of 1850 that James A. Pinney, in company with his father, left Iowa and crossed the plains to California. Later Mr. Pinney drifted up into Southern Oregon, Jacksonville, just as the Rogue River country began to settle up. He ran a pack train to Crescent City, on the coast, for some time. In the summer of 1854 he joined a volunteer company of 90 men and 50 packs under the command of Captain Jesse Walker, B. F. Dowell and others, to go out on the plains to escort in emigrants. They started out east via Klamath and Goose lakes and through the Modoc country, were out all summer and helped many people who were short on rations, and saved many a family from [being] massacred by the treacherous redskins. Jackson sent out a second train with provisions, the most humane expedition ever gotten up by the good people of Southern Oregon. For his summer's work Mr. Pinney received the munificent sum of $50 from the territory. In the early spring of 1863 J. A. Pinney, Uncle Dick Tregaskus and Ruf Johnson left Jackson for the north with three pack trains of 20 mules each--60 mules and a bell horse. As this was the biggest train ever on the road, it created quite an excitement through the Umpqua and Willamette valleys. Arriving at Portland, they all shipped on the steamer for the upper country. At Umatilla they loaded with general merchandise for the basin country. Mr. Pinney stopped at Idaho City, started building stores, of which he built three, and sent his train back after more goods. Abridged from The Jacksonville Post, serialized beginning November 19, 1910, page 1 A shorter version was printed in the Medford Mail Tribune on November 20, 1910, but it was indifferently edited, and contains numerous small differences. It also appeared in the Rogue River Courier of November 18 and the Jacksonville Post of November 19. HOW JOSEPHINE RECEIVED ITS NAME

To the Tribune:

I recently saw an item in the Tribune,

a

narrative telling how Josephine County and Leland derived their names.

It is quite amusing to me how people get mixed up that were not johnny

on the spot.

With them it is only hearsay. I think I am absolutely the only living man that can give anything like a true version of the affair. George H. Parker of Grants Pass, Or. writes me that they want to place a monument over the old grave to preserve its history. Crossing the Plains.

We crossed the plains, my brother, O. B. Twogood, and myself, in 1851,

with 30 teams. Judge Denny, who located Seattle, was captain. We

crossed the Missouri May 10, landed at Oregon City August 20. We lost

everything we had in trying to help others. Not finding work, Sam

Hadley and I rigged up and started for the mines that we heard had been

struck in southwest Oregon. We traveled through the Willamette that was

very sparsely settled and went 250 miles or as far as Deer Creek. There

we found Aaron Rose and family of our county. We purchased a squatter

right and little shack, 10x12. This is now the city of Roseburg.Squatted at Roseburg.

From there we went south five miles, where we found Jesse Roberts,

thence to the mouth of the big canyon, Joe Knott's place, the last

house on the road. We went on to Grave Creek 30 miles farther and found

a nice little valley and good grass. Going 20 miles further south, we

found Ben Halstead's log cabin and ferry boat. We crossed and went down

the south side of Rogue River seven miles to Vannoy's ferry. J. W.

Vannoy and James Tuft had located a ranch there. They were the only two

cabins in the Rogue River Valley.Ascended the Applegate.

Passing up Applegate we passed over the divide and into the Illinois

Valley, some 20 or 30 miles. Here on the north side we found a camp.

Sam Frey was there with a horse corral, where he herded miners' horses.

There we first met Hardy Elliff, Mrs. J. E. Enyart's father. We also

met Judge Morford and partner with a pack train. The judge was killed

in Boise, Idaho in 1864.The next day we passed over the mountain to some creeks, where gold was found. Hadley and I struck camp, pitched our tent and worked ten days, when we concluded we were not cut out for miners. We retraced our steps to Canyonville. Built First Log Cabin.

Hadley went ten miles down the South Umpqua and took up a ranch. Leroy

Knott helped him build the first real log cabin south of Canyonville.

It was then I met Barney Simmons. He and I went 17 miles south and

located the Grave Creek Ranch. I blazed the first tree for settlement

there. A company of prospectors came over the Siskiyou Mountains in

August of 1851. They went down Rogue River and into the Illinois

Valley, then over a mountain, where they found two creeks with gold in

them. There was a Miss Josephine Rollins in the party, so they named

one creek Josephine, the other Canyon. I have been told [erroneously]

since that the young lady was Miss Leland Crowley and was with Jesse

Applegate's train in '45 or '46, the first wagon train that ever came

into Oregon from the south. They did not make more than five miles a

day.War with Indians.

During the Rogue River Indian War of 1853, commonly known as General

Joe Lane's war, my partner, Gale, and a Spaniard from Spain were shot

in bed one night and the house burned at Cow Creek; afterwards six out

of ten Grave Creek Indians were massacred in the Grave Creek House by

Captain Owens' company of volunteers of Jacksonville. Indians were

planted in the same graves they helped to open. They remained "good

Indians" after that.During the war of February '56, my partner, M. D. Harkness, went to carry a message to General [John] K. Lamerick 30 miles down the Meadows. The Indians waylaid him, shot him in the groin and he fell from his horse. The Indians came up, stripped off every rag of clothing, scalped and cut him up in pieces, while yet alive. Whigs Win First Election.

It was in 1854, the month of June, I think, when the first election was

held in Jackson County. The Whigs carried it. M. Lupton and John T.

Miller were elected to the legislature. Lupton introduced the bill

creating Josephine County and changed the name of Grave Creek to

Leland. So you see, Mr. Parker, the name of Josephine Leland would not

look well in history, as Leland Crowley was dead before Josephine

Rollins was in that part of the country.J. H. TWOGOOD.

Medford

Daily Tribune, December 18, 1908, page 4THANKS.--Many years have passed since we were more agreeably surprised than one morning this week. We went into our sanctum and found a keg of cider from Jimmy Twogood, proprietor of the Grave Creek House, with directions to keep it corked tight in order that the "Devil" may be kept out. This precaution was unnecessary, as the Good Templars have got that personage; but we propose to get in even if the devil follows. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, March 10, 1866, page 2 Born.

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville,

March 24, 1866, page

2

At Leland, Josephine Co., Oregon, March 18th, 1866, to the wife of J.

H. Twogood, a son.

DIED:

In

Rockford, Ill. Jan. 30th, at

the residence of Mrs. S. H. Chapin, Leland Custer, youngest son of

James H. and Permelia A. Twogood, late of Leland, Josephine County,

Oregon, aged 10 months and 12 days.Morning Oregonian, Portland, March 25, 1867, page 2 UNCLE JIMMIE TWOGOOD WRITES

Tells of Pioneer Friends in Rogue River Valley, Recalled by the Death of Mrs. Kenney, nee T'Vault.

BOISE,

Idaho, Nov. 26, 1911.--To the Editor: I was very much surprised awhile

back to notice the death of my dear old friend Mrs. Kenney (nee Lib

T'Vault). It was in the month of August 1851 that I first met Col.

T'Vault in Oregon City. At that time General Joe Lane, Delezen Smith,

J. M. Shepard and his brother-in-law were called the "wheel horses of

the Democrat Party" and ran things to suit themselves, but it didn't

last.

It was the spring of 1852 that Col. T'Vault moved out south to the Rogue River Valley and took up a ranch 10 miles north of Jacksonville and called the place where they had the post office Dardanelles. Gold was struck there afterward by Ish, Johnny MacLothlin, Henry Klippel, August Brown and others. In the Indian war of 1853, Doc Rose and John R. Hardin were waylaid and killed near there. Hardin had married Amanda Gall of Galls Creek; [his] widow married Hawkins Shelton of Roseburg, lived neighbors to me here many years. Both are gone now. Of my dear old friends the T'Vaults, the old gentleman and his wife, Lizy, Sainty and George are all gone now, as are Col. John E. Ross, whom I knew in Chicago in the '40s; Mike Hanley, Wagoner, Foudray and hundreds of others. Dave Linn and John Hailey of Boise, Joe Pinkham and James H. Pinney are all that are left. At the rate the pioneers are passing away, I soon will be all alone. I am approaching my 86th birthday. My oldest sister, Mrs. M. L. Satterlee, of 2704 Michigan Avenue, had 150 guests at her 91st birthday party, which was on October 16. Joe Pinkham is manager of the Boise assay office. John Hailey and wife, nee Miss Burrel Griffin, and Jim Griffin that ran the pack train to Crescent City and who is now proprietor of the Pinney theater, which cost $100,000, are all 10 years younger than myself, and are all in good health and vigorous. The weather in Boise is ideal; warm, clear, sunshiny days, no storms or wind yet. It is next to Rogue River Valley, which has the best climate on the coast.--J. H. Twogood. Medford Mail Tribune, December 5, 1911, page 2 Reprinted from the Jacksonville Post of December 2.

At

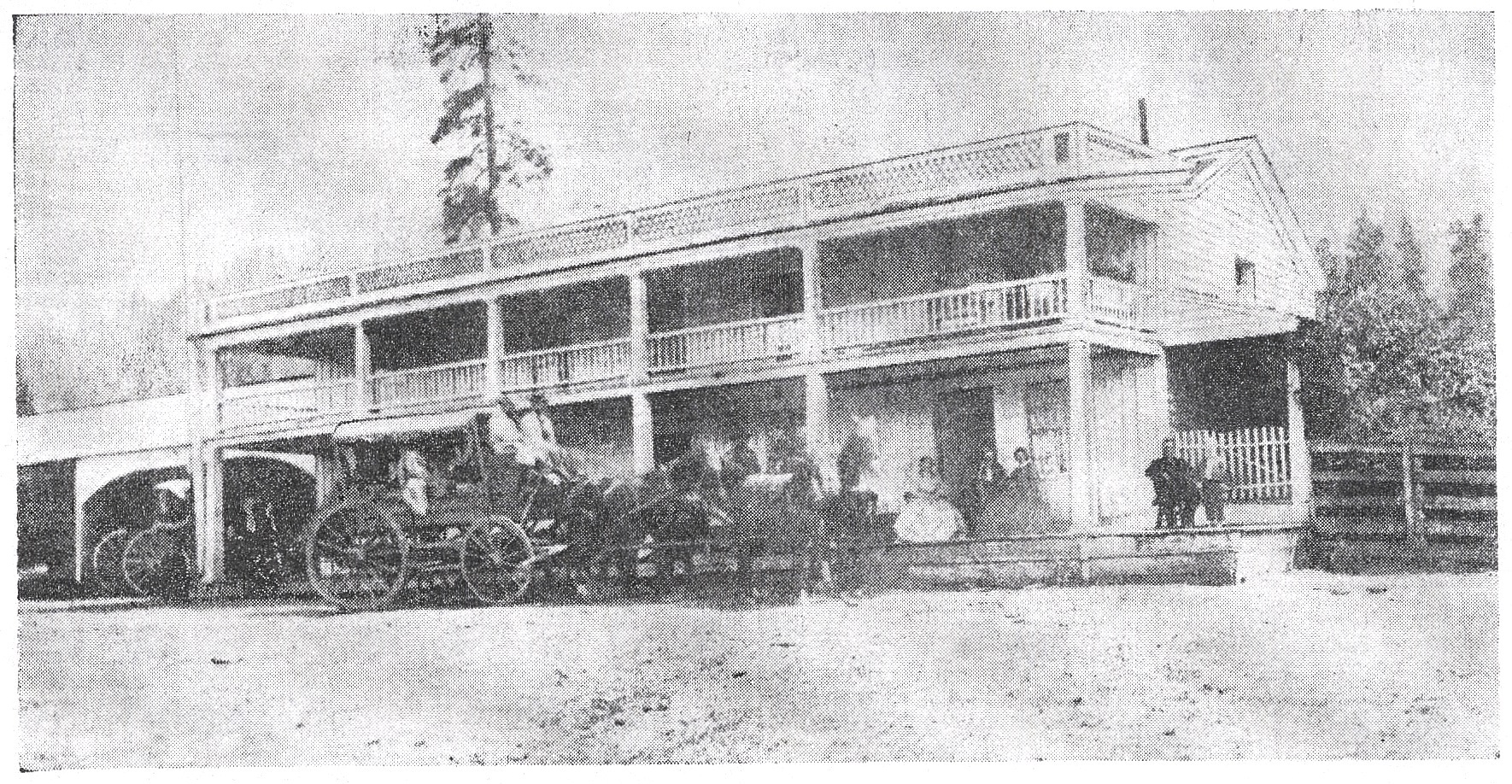

Grave Creek [in 1851] we found a yet-unfinished log house, and several

lion-hearted, iron-handed, hawk-eyed backwoods chevaliers, who

boastfully defied all the Indians in Southern Oregon, not one of whom

should ever again walk over that spot of ground in any other than a

friendly manner. Well was the promise kept. A few years later, when the

savages murdered the settlers, and burned their homes in all the

country round, Grave Creek station stood intact, defiant, safe. In

after years when the Oregon and California stage line was established,

Grave Creek was made a station and rose to greater celebrity than any

other stopping place on the route. The esprit de corps of

the establishment--if the application may be made--was one of the

proprietors, Jimmy Twogood, a man anxious to make money out of the

establishment--knowing how to do it and doing it. He was much respected

by those who knew him, and many of his odd, though seldom senseless,

expressions may still be remembered by those who fortune it was to seek

food and shelter at his Grave Creek hotel. Before placing the stage

teams upon the route a man was sent along the line to designate the

stations and prepare quarters and food for teams and passengers. The

Grave Creek house was a candidate for one of the stations. The agent

noted the apparent sterility of the surrounding country and did not

think it a proper site, because he thought that feed for the teams

could not be raised in the vicinity, and the cost of hauling from other

sections would be considerable. But Jimmy was tenacious, and held that

his place was better adapted for a way station than any other place

within twenty-five miles of it. He was a great stutterer, and when

talking it was his invariable rule to raise his right foot upon the

toes and perform a perpendicular vibration with the heel, at the same

time rapidly slapping his right thigh with the open hand.

"You can't raise anything here, Mr. Twogood," said the agent. "This land in sight around here is too dry and gravelly. I must find a place where they can raise something." To which Jimmy, with his usual accompaniment, replied, "W-w-we c-c-c-can r-r-r-raise s-s-s-some-th-th-th-ing h-h-hh-ere t-t-t-too!" "That is all very well, Mr. Twogood, but I'd like to know what it is that you can raise here." "W-w-w-we c-c-c-can r-r-r-raise h-h-h-hell!" The loud and prolonged run of laughter by the assembled guests which greeted this unexpected finale decided the contest in Jimmy's favor. He got the station. O. W. Olney, "Thirty-Four

Years Ago," Sunday

Oregonian, January 10, 1886, page 3

Henry Riggs, the old Mexican War veteran, stopped with me at the Grave Creek house in '52; my partner, Barney Simmons, being of the same order, they held a sort of social session. J. D. Agnew, my neighbor, was there also. That Agnew, Riggs and Boyakin are in the Missouri class is all right, but [James S.] Reynolds never. When I arrived in Boise in October of 1870 I thought I was a stranger in a strange land, but a dozen men rushed up to me and exclaimed, "Why, Jimmy Twogood, where in h--l did you come from?" I told them I had been back to the beautiful Illinois playing a freeze-out game, got froze out and was here to stay. The next day when I went to the [Idaho] Statesman office to announce our arrival, Mr. Reynolds on hearing my name, said, "Why, you were a partner of Sam and Mac Harkness. I know all about you from way back." From that time on we were great friends. James H. Twogood, "Uncle Jimmy Recalls Jim Reynolds," Idaho Statesman, Boise, May 9, 1909, page 13 I knew James Twogood when he was learning to stutter. If he happened to be coming down [the] street with a package under his right arm and met someone he wanted to talk with, he would change the package to his left so he could pat his leg with his right hand while he talked. M. E. Payne, "Boise Valley in the Days of Old," Idaho Statesman, February 19, 1911, page B8 A Journeyman Tinman Wanted;

To whom good wages

and steady employment will be given. None but a good hand need apply.

BACKUS &

TWOGOOD,

Portland, March 12.

Front

Street.Oregonian, Portland, March 19, 1853, page 3 O.W.O.,

"Our

State Capital," Sunday

Oregonian, September 30, 1888, page 1

SOME INCIDENTS IN THE

NORTHWEST

OF HALF A CENTURY AGO By James H. Twogood

One of the most

interesting events in the history of the great Northwest, which will be

well remembered by many of the pioneers, was the Rogue River Indian

War, which occurred in Oregon in 1853, and resulted in the massacre of

the Grave Creek Indians. This was commonly known as General Jo Lane's

war, a man with whom I was well acquainted, and can well term one of

God's noblemen. I can well remember when he and his bosom friend,

Delazon Smith, controlled the political complexion of Oregon. At that

time the general owned a fine ranch near Winchester on the North Umpqua

River. He was one of the early governors of Oregon and in 1861

represented that state in congress, under that president who was minus

a backbone, James Buchanan.

When the war of 1861 broke out General Lane, a born Democrat, of the state of Indiana, stood with his party, and his sympathies were with the South. Although he stood aloof, it was then and there that he made the mistake of his life. In later years he moved up on Deer Creek, where he led a hermit life until the summons came and he was called across the Great Divide. May peace follow him, as a better-hearted, nobler man never lived. *

* *

At Rogue River there was no settlement

in the spring

of '51, but soon after[wards] placer mines were discovered and people

came pouring in by the hundreds. In the spring of 1853 Jacksonville had

become quite a thrifty town. It was here that Ned Sterling found a

bonanza and named it Sterling Creek. There are some good mines in that

locality today.Early in the month of June the Siwash Indians at Jacksonville became troublesome, plundering and killing. For three years they had been somewhat upon the war path and had killed a number of settlers. A company of volunteers was organized and started after the Indians. General Jo Lane, Indian agent at Umpqua, also came up with a small company, also Captain J. W. Nesmith, from the Willamette Valley. I well remember Captain Nesmith, then a vigorous young man, who wore a flannel shirt and had his pants inside of his boots. He stuck me for 50 lbs. of bacon to be charged to the government. There was no butter in those days, and we only had a little bacon and needed that to fry venison in and to feed our neighbors, and Captain Owens and his company of volunteers, who were patrolling the road between Canyonville and Jacksonville, which was 40 miles south. Capt. A. Noon [?] had 40 men in his company, and of course we could not afford to feed them when we were obliged to keep men on the trail who were serving us for nothing. They managed to get to Grave Creek and there had 120 meals which cost them $11 each. As there was not an Indian in sight at Grave Creek from June until September, my partner, A. S. Bates, took $50 of the company's money and went out to assist General Lane. He soon came home broke. We were out over $1,200 for meals, and never were paid a cent. During that summer there were quite a number of whites killed, but a still larger number of Indians, until after General Lane was wounded in the fleshy part of his arm. He finally succeeded in negotiating a treaty with the Indians while still carrying his arm in a sling. Wharf at Portland.

In the month of August, 1851, a wharf

was built at

Portland and ships came up from San Francisco with cargoes of supplies.

They came around the Horn, and it took them 160 days to make the trip.

It was here that I first met Captain [Martin] Angel. He was running the

little tug boat Black

Hawk, which

carried most of the supplies up the Willamette River to Oregon City, a

commercial center 12 miles above Portland, which was then a mere

stopping place.Captain Angel came out in the year of '52 and located on a ranch near Jacksonville. During the war of '53 he was waylaid and killed. Colonel W. G. T'Vault, whom I knew in Oregon City in '51, came out the next year and located a ranch 10 miles north of Jacksonville, which he called Dardanelles. Doc. Rose and John R. Hardin, the latter an ex-member of the Oregon legislature, came out and settled on Galls Creek and married. Amanda Gall settled in the Boise Valley in the '60s. Rose and Hardin were guarding the road between Dardanelles and Jacksonville, and were both killed by the Indians. After Rose was killed, Mrs. Rose and her brother-in-law, Pete Miller, vacated their home and stopped at the Grave [Creek House.] No Work for Immigrants.

During the summer of '52 there was a big

immigration, and those who came to the Willamette Valley could not find

work. Times were hard, and there was no money. Hundreds of the

newcomers camped out and flocked to Southern Oregon to work in the

mines. They were driven back to the valley by a heavy snow, and we had

to feed them whether they had money or not, and the majority of them

were broke. The result was that we were soon eaten out of house and

home and all the supplies we had laid in during the fall were

exhausted. Flour went up to $1.25 per pound, but could not be bought at

any price, as there was not a pound to be had. For a month we lived on

venison and salmon straight, without even salt to flavor it.During that time a tramp named Wesley Gale came in from California. His stock in trade consisted of a pair of blankets and a fiddle. He was lame, but he seemed a jovial sort of a fellow, and Barney and I invited him to share our hospitality of salmon and venison straight, which he readily accepted. James A. Pinney and Gale were friends in 1850, and he certainly proved himself to be a noble, good man. In the spring of '53 we got him to go 10 miles north and take up a ranch at the crossing of Cow Creek. He hired an ox team to haul logs to build him a cabin and was obliged to pay $10 per day for his dray animals. We furnished him with considerable provisions and he was to open a bakery, which would have paid well. While he was there a Spaniard came along, and being lonesome Gale invited him to stay with him. In the month of June during the Indian war the Umpqua and Grave Creek Indians stole into their place and killed both of them, and then burned their house. Town Named After Gale.

The post officer a few miles above

called the place

where the cabin stood Galesville, and that name is the only thing left

by which the memory of Wesley Gale is kept fresh in the memory, as his

story is well known and the place is often visited.After Gale was killed there was not an Indian to be seen. In July a pack train went from there to Scottsburg for supplies. An Indian we called Thick-Lipped Jim was hired to ride the bell horse and help pack. He certainly was a noble specimen of humanity. He stood six feet in his bare feet, weighed 170 pounds and was a fine athlete. I was informed that he was the Indian who in April '51 stole into a white man's camp [David Dilley] while he was asleep, and stealing his gun which lay beside him, shot and killed him. Doc. Revis and Bill Ganey, the other members of the party, escaped and returned to Wolf Creek, from whence they started and took up a ranch. Shortly after this Jim visited Wolf Creek and Bill Ganey and others took him prisoner, lashed him to a horse and took him to the Grave Creek House, where they insisted on hanging [him] to a big oak tree beneath which [Martha] Leland Crowley was buried. After the crowd had taken a drink at my expense, I informed them that there would be no necktie party there while I was in command, so after some talk they started back to Wolf Creek, where poor Jim was court-martialed. The verdict was that Gale had been killed and there must be a hanging. Poor Jim was given a glass of firewater, placed on a white horse, which was led out under a tree. A rope was thrown over a limb and one end adjusted around his neck. Ganey said: "Jim ka-nika bits mika to kum ancota." [Jim, where are my bits, six a long time ago.] Jim said: "Halo nika six bits, spose nika is kum, mika potlach." [I don't have the bits, friend, but if I get it I'll give it to you.] The horse was led from under him and his body left dangling there for several days. Ever after Ganey's dunning Jim for six bits the place was known from one end of the road to the other as the Six-Bits House. Meeting with Indians.

It was about the first of September when

we thought

the war was over that Barney Simmons and I rode up the creek to look

after the stock. Just one mile above the house in the valley we spied

three Indians with guns. We stopped and turned back when they sang out:

"Chocco six pemica tickey florh [kloshe?] wawa." [Come, friend, I want to have a good talk with you.] We told them that if they would

lay down their arms we would consider the proposition. They hesitated a

few minutes, saying that they were good friends, had good hearts and

were not mad at the whites. We told them about Gale being killed, but

they claimed to know nothing about it and said it must have been whites

or Cow Creek Indians. We told them Jo Lane had made the treaty with the

Rogue River Indians and that war was over. They said they wanted to

come down to the house and trade with us, as they wanted flour, and

wanted to know if it would be safe. We assured them that it was, always

having made it a point never to lie to an Indian, and we did not know

at that time that we were leading them into a death trap the next day.Captain Owens was still patrolling the road, and had gone below a few days before. The next morning the whole tribe of Grave Creek Indians came down to the house, squaws, papooses and all. It seemed quite natural to have them back after they had been absent three months. They seemed highly pleased to get back to the old place once more. After a short visit three of the bucks went down the creek to the old hunting grounds after a deer. We were all chatting away, having a regular picnic and as happy as innocent clams, when Captain Owens and his company of volunteers rode up. Seeing the Indians, he immediately gave orders to surround the house. The bucks were driven into the store room and tied with ropes to the logs. The squaws and papooses were placed in a little log cabin we had built outside for a bake oven. Six bucks were in the store room and six volunteers with revolvers stood guard over them. Owens placed guards outside to watch for the three bucks coming in from the creek. There was a big pine tree 50 feet north of the house. It was four feet through and 100 feet high. At the base was a hollow, which was a desirable place for campers to build fires on a rainy night. The tree was half burned down and not safe to be left standing, so we chopped it down and the trunk was still there. Mrs. Dr. Rose and I were sitting on that log talking, when things got busy. We had supposed that when the three bucks came in from the creek they would be taken into the camp, and Captain Owens would have manhood enough about him to give them a fair trial, but it seems when at Canyonville a few tenderfeet, who had just crossed the plains, had been added to his company, and were en route for the mines. These pilgrims from the East were secreted behind the house with strict orders to take the bucks prisoners. A Tenderfoot Charge.

In a short time the bucks came back up

the creek,

each one carrying a deer on his shoulders. The tenderfeet from the

East, instead of hiding their guns and greeting the bucks in a friendly

manner and then capturing them, rushed from the hiding place, guns in

hand, and charged down on the bucks. The squaws, seeing the men, called

to the Indians, who dropped their loads and started down the trail on

the run. They had not gone 100 yards when the guards began shooting,

but having muzzle-loading rifles and pistols, did not make any fatal

shots, only hitting one Indian in the calf of the leg. He dug the

bullet out and showed it to me afterwards.When the shooting began outside, I heard the old chief inside, whose hands were tied behind him, and who was bound to the logs on [sic] the cabin, shout to his people to get away or they would all be killed. Struggling frantically himself, he succeeded in freeing his hands and grabbing a shovel which was standing close by; he struck Tom Frazelle, who was standing guard over him, a blow on the hand which knocked the pistol from his hand. Both he and the chief grabbed at it and both succeed in grabbing the gun, Tom getting it by the butt and the chief by the muzzle. A struggle took place and Tom being hard pressed pushed the muzzle to the chief's body and fired, killing the old chief almost instantly. When I heard the shooting inside the house I jumped up and ran to the place, pulled aside the blanket used for a door, but could see nothing through the dense smoke which filled the room. As soon as the smoke had cleared away I ventured in the building, but there was not an Indian left to tell the tale. In their number was Tipsien Bill, an Indian who did not know what fear meant. Give him a knife and he would tackle a grizzly bear at any time, but his life went out while tied to the wall in that small cabin. Mrs. Leland Crowley, who crossed the plains in the early '40s with Jesse Applegate, and who drove the first train into Oregon from the south, died of consumption at Graves Creek. Knowing that the Indians would dig up [her] body and rob it of all clothing, the members of the party dug a grave 10 feet in diameter and four feet deep. During the night they corralled the cattle on her grave, thinking to obliterate all trace of the burying place, but they were hardly out of sight next morning when the Indians pounced down upon the grave, dug up the body and stole all the clothing. Little did these Indians think at the time that they were digging their own graves; it crops out those we killed at the house we afterwards learned were the same band that robbed the body--planted them in the same hole. At the time I felt very badly over the affair, which I regarded as cold-blooded butchery, but in after years when the Indians again broke out and began their work of slaying and stealing, I was glad of it, for I knew it had saved the lives of many white men. Since then I have come to the conclusion that the only way to make an Indian good is to bury him beneath four feet of ground. Evening Capital News, Boise, Idaho, April 10, 1909, page B6 O. B. TWOGOOD.

(Late Backus & Twogood.)

WOULD inform the public that he has now on hand a

superior lot of COOKING

and PARLOR

stoves,

together with a good assortment of Tin, Japanned, Sheet-Iron and

Holloware which is offered at rates that will not fail to suit the

purchaser.

The public are invited to call and be convinced, at the old stand, Main St. Oregon City, Feb. 11, 1854. Oregon Spectator, Oregon City, January 27, 1855, page 4 AN EXPRESSMAN KILLED.--The Yreka Union has been informed that Mr. Harkness, one of the partners of the Grave Creek House, in company with Mr. Wagoner, of Jacksonville, O.T., was taking the express from Grave Creek to McAdams, down Rogue River, and that the Indians fired upon them, killing Mr. Harkness. One ball passed through the clothes of Mr. Wagoner, without, however, doing him any injury. Marysville Daily Herald, Marysville, California, May 17, 1856, page 3 I will cite two cases in Southern Oregon which happened in the '50s. In those times everybody "packed" a gun who was able to own one. I plead guilty to the charge myself. I was strapped to a young Colt, and nights I slept with it under my head. That was from 1851 to 1856, during the Rogue River Indian War. [James] Simeon Oldham, a sporting man from Rock Creek, Mo., crossed the plains in the early times and settled in the Willamette Valley. He went out to Yreka, Cal., in the summer of '52, with a little sorrel racehorse that he called the "Gold Digger." It was truly named, for he could dig out more gold in a quarter-mile dash in 20 seconds than most men did all summer. On his return trip the horse got lame, and he left him with me at Goose [Grave?] Creek. It was there that I first got acquainted with Oldham; as fine a man as one would wish to meet. In after years, when Southern Oregon got more thickly settled, they had a race course near Jacksonville. It was here, on this track, one spring in the '50s, that Mr. Oldham got into an altercation with Dr. Alexander, a noble, good man. Everybody was his friend. Mr. Oldham must have been under the influence of liquor, but that is no excuse. He pulled his gun and shot the doctor dead. He was tried and acquitted by a "lower court," but the brand of Cain was placed upon his brow, and, like others, he became a wanderer upon the face of the earth, and never knew what "peace on earth, good will to men" was, ever afterwards. He wandered up here to Boise in the early '60s, and then drifted over to Silver City, where a young man shot him. Simeon was a brother of J. B. Oldham, ex-sheriff of Ada County, whom all the oldtimers knew and respected as a man, although a gambler. He was as true as steel and "on the square," ever ready to extend the glad hand and share his purse with his fellow man. They don't make any kinder-hearted men than J.B., but he has gone to his long home. There was a Captain Abel George, captain of a volunteer company during the Rogue River Indian War of 1855-56. He was a fine-looking man, with a nice family, and was a neighbor of ours, living 13 miles south of us. Some time after the war he went out to Jacksonville and got full of booze, and went to Clugage & Drum's livery stable, where a colored man was getting onto his horse. George jumped on behind, in his wild, crazy fit; they both fell off, and the colored man was dead. George was tried and acquitted by a "lower court," but his life was wrecked. And there was "Ace" Abbott. In the early '50s, when I first knew him, he was a good man, but something of a bluffer. He lived south of us, in the same county, near Kerbyville. He, too, had to get his man with a gun--I think he was a colored man. Abbott was tried and turned loose by a "lower court," but his life was wrecked. Billy Abbott carried the mail on horseback, and stopped with us in the fall of '55, during the war. They all came up here [i.e., the Boise area] in '63 and settled in Garden Valley. At Placerville, one day, "Ace" got into a shooting scrape with others. When the smoke cleared away it was found that he had killed his brother, Billy. Abbott was again tried by the "lower court" and swung clear. He sent for me to come up and buy his ranch, in the winter of 1870. I went up and found two feet of snow and did not purchase it. Abbott sold it in 1871 or '72, left the country and went to Texas, where he could get rid of his troubles, as he thought, but alas! the poor deluded man found a judgment hanging over him from a higher court, that said: "Thou shalt not kill." It set him crazy--conscience would not down, so he passed in his checks, going via the double-barreled shotgun route. Oh! if men would only stop to think! JAMES

H. TWOGOOD.

Boise,

December 6, 1907.

"Thou Shalt Not Kill," Evening Capital News, Boise, Idaho, December 7, 1907, page 10 Leland Creek House.

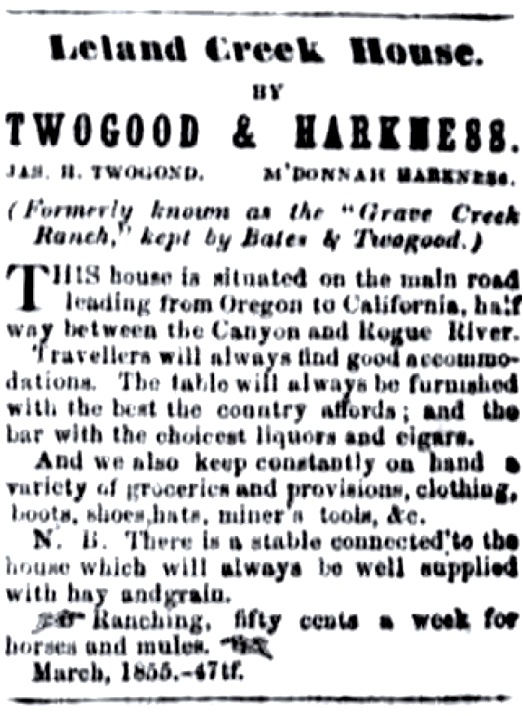

BY TWOGOOD & HARKNESS. JAS. H. TWOGOOD. M'DONNAH HARKNESS. (Formerly known as the "Grave Creek Ranch," kept by Bates & Twogood.)

THIS house is situated on the main road leading from

Oregon to California, half way between the Canyon and Rogue River.