|

|

The Lupton Massacre A list of white participants in the massacre, as compiled from various sources. Most are identified by only one source, making this list unreliable: Allen

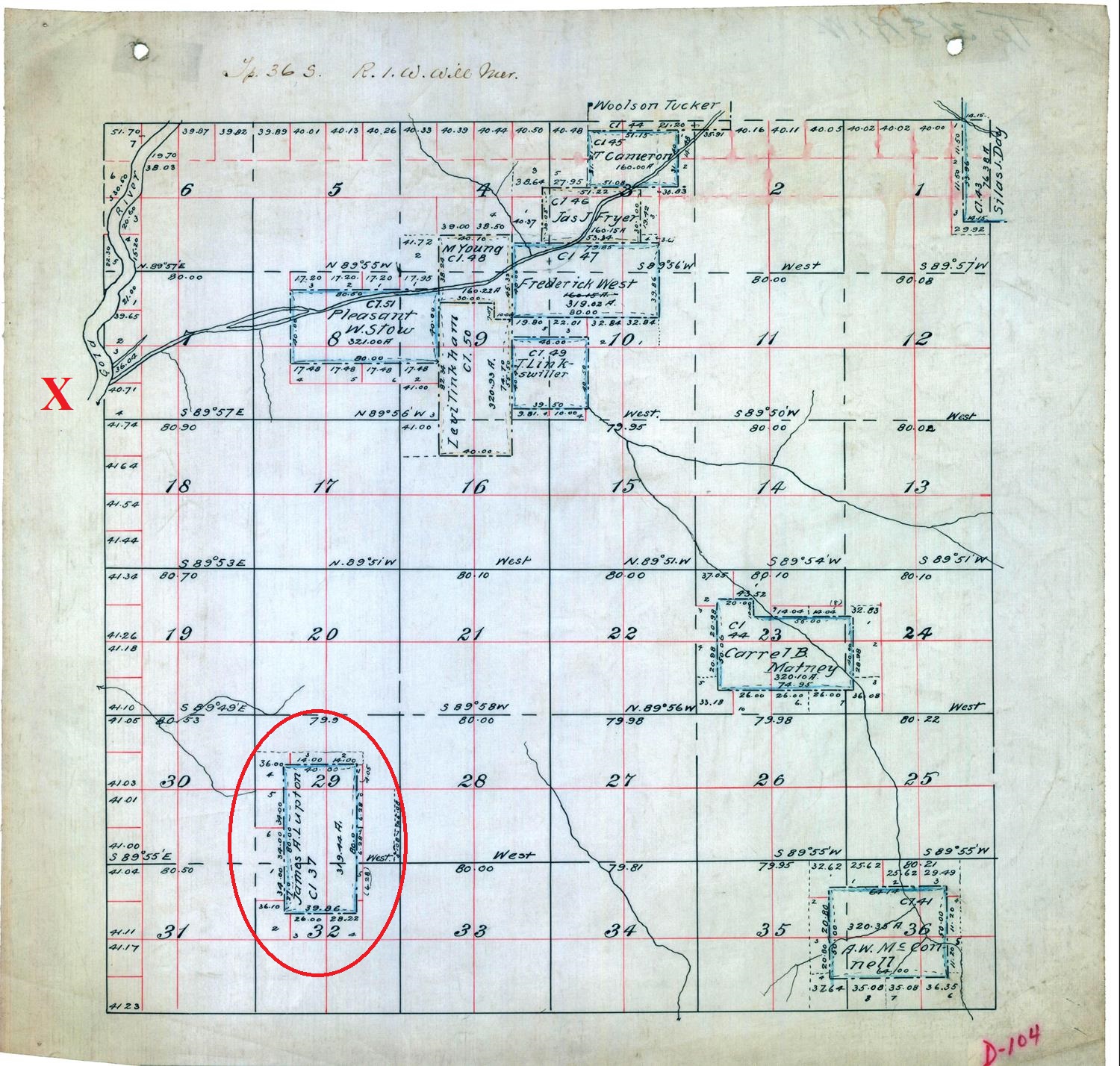

James Firman Anderson Angus "Hank" Brown James Bruce Cotes [Jerome B. Coates?] Patrick Dunn Asa Fordyce R. R. Gates Burrel B. Griffin John Hailey T. Smiley Harris Captain/Colonel Hays/Hayes ("of Phoenix") J. Herriford/Hereford Claton Heuston John K. Jones James A. Lupton J. W. Miller J. N. T. Miller John F. Miller John S. Miller Newcomb Jonathan A. Pedigo E. C. Pelton George Ross George Shepherd/Sheppard James William Walker Giles Wells William White Captain Robert L. Williams M. M. Williams R. M. Wooden John Bennett Wrisley  James Lupton's Donation Land Claim is circled; an "X" marks the approximate location of the Indian village at the mouth of Little Butte Creek. Lupton's property was centered between today's Crater Lake Highway, McLoughlin Drive, Vilas Road and Gregory Road, south of White City. -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

THE ROGUE RIVER WAR--ITS CAUSES.--The Yreka Union, of the 5th ult., says: "On Thursday last (November 1st), a party of sixteen men, under Mr. Tupper, of Shasta Valley, fell in with a large body of Indians in the mountains dividing the waters of the Klamath and Shasta rivers. After a brief engagement, and losing one man, the whites were compelled to retreat." We learn from reliable persons that the true version of the case is that a party of Shastas, numbering twelve warriors, have resided near the Mountain House upwards of eighteen months, engaged in hunting; that during that time they have never molested the stock or other property of any of the farmers in that vicinity. Mr. Tupper and his party camped one night near the Mountain House, and "staked out" an old pack horse; in the morning the horse was gone, and, of course, "the Indians must have stolen him." Mr. Tupper and party waited until near daylight of the following day, and then stole upon the camp of the unsuspecting Indians and commenced firing upon them; the Indians aroused, gained their arms, and whipped the valiant party, who most ingloriously fled back to their camp, where they found their old horse, who had, in feeding, pulled up his stob, but had never been two hundred yards from the camp. The news of the fight spread through the country, and troops were ordered out from Forts Lane, Jones, and the Reservation, after the Indians. A few days before the above occurrence, the Indians on the Reservation--a most miserable location, known in the Indian language as the "starving land"--obtained written permits from the agent to go up the river to catch salmon. They encamped near the house of a farmer named Wilson. While there, Wilson accidentally killed an ox, and having no use for it, he gave it to them. While engaged in cutting up and drying it, Lieut. Sweitzer, U.S. Army, who had been ordered out against the Shastas, came to them and advised them to return forthwith to the Reservation, as they might be mistaken for hostiles. They packed up and started back, getting within a few miles of the agent's house that night--the young and able-bodied men going on to the sweat houses, leaving the squaws, children, and old men to go in the next day with the packs. On the day before, while they were engaged in cutting up the ox given them by Mr. Wilson, who had gone off visiting, some foolish fellow passed, and "seeing what was going on, made his escape," and reported that "the Indians had killed Wilson, and were slaughtering his cattle in his yard." The alarm was sounded, a Maj. Lupton raised a company of ninety men, pursued after and surrounded the camp of squaws; they fired a volley into the camp, when the Indians fled into the chaparral, and returned the fire from guns, bows and arrows, some two hours, when one of Lupton's company espied a squaw, with whom he had lived on terms of intimacy, and called to her to come to him. She obeyed, and produced the written permits from the agent, and also assured the company that the ox had been given them by Mr. Wilson, and referred to him for the truth of her statement. She was directed to tell the others to come out that "they should not be hurt, that it was a mistake." The Indians, trusting to the faith of the white man, came forth, when they were surrounded, and twenty-one women and children, and three old men were ruthlessly shot down, the remainder making their escape. Lupton was shot by an arrow in the hands of one of the squaws, and mortally wounded; when dying, he wanted to know of the surgeon of the post, who was in attendance upon him, "if he didn't think it was d----d hard for him to be killed by an Indian in that manner." The above particulars we have obtained from various sources, and are satisfied that they are literally correct, and that the Rogue River war is attributable to these causes alone. Humboldt Times, Union, California, December 1, 1855, page 2 -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

List

of letters remaining at the Oregon City post office as of March 31,

1851 is provided by F. S. Holland, postmaster: …James

A. Lupton…

Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, April 4, 1851. Reprinted in Julie Kidd, ed., Oregon Newspapers Abstracts, Vol. 1, Portland 2001, page 197 Camp

on Rickreall Creek

My Dear

FriendOregon Territory Dec 25 of 51 Sir I avail myself of this opportunity of writing you before I leave this place. The gold fever has broke out afresh in this country, which I presume you have had some account of. The new discovery made last winter is on the Klamath River, the dividing line between Oregon and California. The gold is said to be found in great abundance. I have seen some of the gold, which is very coarse, and the prospect is so flattering I have been induced to embark in the enterprise. I raised a company to proceed immediately to the mines, and I am happy indeed to have the honor to inform you that I have been selected by the unanimous consent of the company to conduct while prosecuting the journey. I expect to arrive at the place of our destination about [the] middle of March. The intermediate country through which we have to pass is infested by hostile Indians, who attack the emigrant at every point. It appears that they are determined never to allow any emigrants to pass unmolested, but we are fully prepared at [all] points. This is the first time that I have had the opportunity of seeing the great Willamette Valley. I assure you that it is a very rich and fertile country. It fully meets my expectation. It is well watered, has plenty of prairies, and for all farming purposes I have never in all my travels have seen a country better adapted for agriculture than this. With your permission, I will inform you of what I have been doing. Last spring I re-engaged in the government service at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River as an assistant in the construction of the barracks. I was afterwards appointed by the chief quartermaster of this department as his agent to conduct the transporting of goods and all necessary supplies for a fort at the Dalles of the Columbia River. In this capacity I have been acting until recently, the pay being tolerable good, two hundred and fifty dollars per month. I have left this situation for uncertainty in the gold mines; whether I shall make anything by the operation or not remains for the future to decide. I have made a great many good and influential friends since I came into this country. I have not, among all the officers composing the Rifle Regiment, one enemy. I was very glad to hear from your family by the letter which I received from Mrs. Holmes. You will receive for yourself and family the assurance of my most distinguished consideration. Southern Oregon Historical Society MS 377 Camp

on Rickreall

Dear SisterI have at last returned from the mines, but have not brought much of the oro with me. I still have [a] small share of it. I am about returning to the mines, and in fact I will leave tomorrow to try my luck once more. I done pretty well when I was in the mines; I made about seven hundred dollars in about two months; that is what I call doing tolerably well. The gold mines has been very rich, and it is reported that new diggings has been discovered on Rogue River which is said to be very extensive. This place is in Oregon near its southern boundary. The miners have had several battles with Indians in that section of country in which several persons on both sides has been killed. It is necessary for persons traveling through that country to go in large parties to ensure safety. A majority of those who were engaged in the mines at [the] time I was there made a considerable of money. The average was about ten dollars per day, but some made twice as much and even three times as much. I have seen men take out a hundred and fifty dollars in one day. All the money that I made was made in speculation and not by digging. I built the first house in Shasta Valley. Since that time there has been a large city built, the name of which is Shasta City, and when I tell you this town of fifty houses or more, and a thousand tents, was built in less than two months from the time I put up the first house, which was only a few days after the discovery of Shasta mines. Give my compliments to Mr. Holmes and say to Gen. Lane as elected delegate to Congress from this Territory. You spoke to me about going home, but I cannot go as long as I can make a living here so easily. I can make as much here in [a] week as I could in the States in two months. Last summer I made in five months fourteen hundred and fifty dollars doing nothing, and that clear of all expenses. This you may think is an exaggeration, but it is not. It is the fact. But that it takes a good deal to support a person here is also a fact. Please send me some newspapers and oblige yours To Mrs. Holmes Southern Oregon Historical Society MS 377 In 1852 [John M., A. W. and Silas Wolford] moved from Ohio to Polk County, Iowa, and in the spring of 1853 started across the plains, in company with A. Ireland and Joseph Stevenson, coming by way of Humboldt River and Klamath Lake to the Rogue River Valley in Oregon. There was then considerable trouble with the Indians, and at Alkali Valley they joined Major Lupton's company and came to Jacksonville, spent but a short time there and then moved on to the North Umpqua. Not being satisfied there, they came to Cottonwood and engaged in mining until the fall of 1854. Harry Laurenz Wells, History of Siskiyou County, California, 1881, page 134 They succeeded in raising about 30 men, some of them from disbanded Company A, Captain Harris commander, which fought and defeated the Indians at Table Rock on the day of the massacre of the Wagoner family. A young man by the name of S. A. Mowder, clerking in Captain Harris' store in Sterlingville, accompanied the expedition. "Battle of the Cabins," Sunday Oregonian, Portland, April 15, 1900, page 32 1853

SUNDAY, JUNE

12. This is Sunday morning. I attend to my domestic duties, which are a

thousand and one, arrange my hair and sit down with my Bible to read.

But am interrupted by Mr. [Alexander

J.?] McIntyre and Lupton; they take dinner with us

and go to Constants'.MONDAY, NOVEMBER 21. Monday morning. It has ceased to rain last night and some prospect for fair weather. Maj. Lupton has just brought some thirteen chickens here and offered them for twenty dollars, and so we have concluded to take them. Oscar Osburn Winther, Rose Dodge Galey, eds., "Mrs. Butler's 1853 Diary of Rogue River Valley," Oregon Historical Quarterly, December 1940 On the morning of the first Sunday in June, 1853, Major James A. Lupton and myself, while on our way to Jacksonville via the Table Rock trail, leading over the mountains from Umpqua Valley, having camped the night before on Trail Creek, a tributary of Rogue River, rode into an Indian ambush on the north side of the river, a short distance above Thompson's Ferry. We had taken a trail leading to the river about two or three miles above the ferry, instead of the right one leading direct to it. On entering a clump of willows on the river's bank we found themselves confronted by a band of about 40 Indians in war paint, armed in part with guns and pistols, others having bows and arrows, which in close quarters are more effective weapons in a fight than the guns used at that time. Major Lupton, as he was generally called, was not an Army officer, but came to Oregon in 1849 as wagon master for the rifle regiment. He was at this time engaged in the business of packing. We were partners, and a more honorable, upright and energetic man it has never been my fortune to know. He was brave to rashness. He was just ahead of me on the trail, and as he halted I noticed he reached for his pistol in the holster of his saddle. I spurred my horse to his side, and putting my hand on his arm told him not to shoot, immediately addressing the chief, who was standing in front of us but a few paces off, in Chinook, asking him what was the matter, and how far it was to the ferry. This, of course, after saying to him, "How do you do?" To none of these inquiries did he reply, but stood sullen and motionless. Lupton still held his revolver in hand, ready for action, but not raising it, awaiting the outcome of my talk with the chief, who proved to be "Cutface Jack," chief of a wild band of upper Rogue River Indians. Knowing enough of Indians to feel certain that they were lying in wait for a larger party than two persons, and having heard that a raid was contemplated by a company of white men to their country to rescue a white woman who was supposed to be held a prisoner among them, I immediately decided that the proper thing to do was to assume that it was that party, not us, they desired to intercept. I kept close watch of the chief as he proceeded to question me in turn, knowing it was of the utmost importance to understand every word he uttered, as well as to make him understand me, which was a task not easily performed, as neither of us were proficient linguists in the Chinook jargon. He asked who we were, what we wanted, and where we were going. I told him we were from the Willamette Valley, had come across the mountains the day before, and had camped for the night a few miles back, giving him the exact spot, which I divined that he well knew, as I did not think that we could approach so near a party of hostile Indians without their knowledge. He was satisfied with my answers, and immediately came forward and gave me his hand to shake. He did not offer it to the Major, as he regarded me as chief, for I had done the talking. This was well, as the Major told me afterwards that he would have refused it, as he expected at any moment to have use for his right hand in handling his pistol. From a sign made by the chief the warriors all dispersed into the bushes, and we passed on to the ferry without further molestation. My companion, initiated by the occurrence, proposed going back and taking a few shots at them, as he said, just to teach them better than interfere with white men. When we arrived at the ferry, Thompson informed us that "Cutface Jack" and his party were looking for a company of volunteers under Captain Lamerick, who a couple of days before had captured four of their party, and while holding them prisoners as hostages for the release of the supposed white woman, who was believed to be held a prisoner by their tribe, two of them in trying to escape in the night had been shot and killed, the other two escaping to the Indian camp with the news. Cutface Jack had rallied his band of warriors and was on the warpath, and he was trying to intercept Lamerick's party on their return from their trip up the river. Instead of this, he informed us, they had returned to Jacksonville by a more southerly route, and thus had eluded the ambush of Cutface Jack which we fell into. We arranged with Thompson to send a man with some trusty Indians back to move our camp to his ferry, as he had a squaw for a wife, and was on good terms with the Indians. We felt that the camp would be safe under his care. The next day was election day, Jacksonville polling a very large vote. Having cut and stacked a lot of hay and built a cabin across Bear Creek from Jacksonville, about 12 miles distant, in what was conceded to be exclusively Indian country, as no settlers had located across the creek in that vicinity, Lupton had gone on the plains to buy cattle from the immigrants, and after I had completed the preparations he desired me to make, I started on horseback for Marysville, on what was to me most important business, seeing the person who later became the partner of my life. . . .

[Returning to the Rogue

Valley in early September 1853,] Lupton

came in from the plains with a lot of stock, and was surprised to find

even the arrangements he had left at the camp were not disturbed. Half

a dozen pack covers, a hatchet and some nails were taken, but were

brought back by order of little Chief John.When locating on the place,

I made a treaty with this Indian, paying him for the use of the land

from which to cut hay, and for the stock to range, naming specifically

that the hogs were to have right to camas and acorns. The hay was

hauled to Jacksonville the following summer and sold, as the winter was

mild and it was not needed for the stock.

Lupton later became sole owner of this property, and after living there two years was killed by the Indians in a battle at the mouth of Butte Creek. He was leading a company of volunteers, and while charging in the brush was pierced through the body by an arrow from an Indian bow. The Indian was lying on his back and sprung his bow with his feet--a very effectual way, as great force can thus be given to the bow to speed the arrow. Smiley Harris, who was a well-known character of Jacksonville many years ago, has been granted a pension. He is a veteran of the Mexican War and resides in Idaho. "Local Notes," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, March 25, 1901, page 3 Hard copy at SOHS. On the morning of the first Sunday in June 1853, Major James A. Lupton and myself, while on our way to Jacksonville, via the Table Rock trail, leading over the mountains from Umpqua Valley, with a drove of hogs which we were taking to the Rogue River Valley to feed on camas, the feed for hogs at that season of the year--we were also looking for a place to cut hay--and having camped the night before on Trail Creek, a tributary of Rogue River, rode into an Indian ambush on the north side of the river, a short distance above Thompson's Ferry [later Bybee Ferry--where Table Rock Road now crosses the Rogue River]. We had taken a trail leading to the river about two or three miles above the ferry, instead of the right one leading direct to it. On entering a clump of willows on the river's bank we found ourselves confronted by a band of about 40 Indians in war paint, armed in part with guns and pistols, others having bows and arrows, which in close quarters are more effective weapons in a fight than the guns used at that time. Major Lupton, as he was generally called, was not an army officer, but came to Oregon in 1849 as wagon master for the rifle regiment. He was at that time engaged in the business of packing. We were partners, and a more honorable, upright and energetic man it has never been my fortune to know. He was brave to rashness. He was just ahead of me on the trail, and as he halted I noticed he reached for his pistol in the holster of his saddle. I spurred my horse to his side, and putting my hand on his arm told him not to shoot, immediately addressing the chief, who was standing in front of us a few paces off, in Chinook, asking him what was the matter, and how far it was to the ferry. This, of course, after saying to him, "How do you do?" To none of these inquiries did he reply, but stood sullen and motionless. Lupton still held his revolver in hand, ready for action, but not raising it, awaiting the outcome of my talk with the chief, who proved to be "Cutface Jack," chief of a wild band of Upper Rogue River Indians. Knowing enough of Indians to feel certain that they were lying in wait for a larger party than two persons, and having heard that a raid was contemplated by a company of white men to their country to rescue a white woman who was supposed to be held a prisoner among them, I immediately decided that the proper thing to do was to assume that it was that party, not us, they desired to intercept. I kept close watch of the chief as he proceeded to question me in turn, knowing it was of the utmost importance to understand every word he uttered, as well as to make him understand me, which was a task not easily performed, as neither of us were proficient linguists in the Chinook jargon. He asked who we were, what we wanted, and where we were going. I told him we were from the Willamette Valley, had come across the mountains the day before and had camped for the night a few miles back, giving him the exact spot, which I divined that he well knew, as I did not think that we could approach so near a party of hostile Indians without their knowledge. He was satisfied with my answers, and immediately came forward and gave me his hand to shake. He did not offer it to the Major, as he regarded me as chief, for I had done the talking. This was well, as the Major told me afterwards that he would have refused it, as he expected at any moment to have use for his right hand in handling his pistol. Upon a sign made by the chief, the warriors all disappeared into the bushes, and we passed on to the ferry without further molestation. My companion, irritated by the occurrence, proposed going back and taking a few shots at them, as he said, just to teach them better than to interfere with white men. When we arrived at the ferry, Thompson informed us that ''Cutface Jack" and his party were looking for a company of volunteers under Captain Lamerick, who a couple of days before had captured four of their party, and while holding them prisoners as hostages for the release of the supposed white woman, who was believed to be held a prisoner by their tribe, two of them in trying to escape in the night had been shot and killed, the other two escaping to the Indian camp with the news. "Cutface Jack" had rallied his band of warriors and was on the warpath, and he was trying to intercept Lamerick's party on their return from their trip up the river. Instead of this, he informed us, they had returned to Jacksonville by a more southerly route, and thus had eluded the ambush of "Cutface Jack" which we fell into. We arranged with Thompson to send a man with some trusty Indians back to move our camp to his ferry. As he had a squaw for a wife and was on good terms with the Indians we felt that the camp would be safe under his care. The next day was election day, Jacksonville polling a very large vote. Having cut and stacked a lot of hay and built a cabin across Bear Creek from Jacksonville, about 12 miles distant, in what was conceded to be exclusively Indian country, as no settlers had located across the creek in that vicinity, Lupton had gone on the plains to buy cattle from the immigrants, and after I had completed the preparations he desired me to make, I started on horseback for Marysville, on what was to me most important business, seeing the person who later became the partner of my life. . . . [After the 1853 Rogue River Indian War] Lupton came in from the plains with a lot of stock and was surprised to find even the arrangements at the camp were not disturbed. Half a dozen pack covers, half a dozen lash ropes, a hatchet and some nails were taken, but were brought back by order of little Chief John. When locating on the place I made a treaty with this Indian, paying him for the use of the land from which to cut hay and for the stock to range, naming specifically that the hogs were to have right to camas and acorns. The hay was hauled to Jacksonville the following summer and sold; as the winter was mild and it was not needed for the stock. Lupton later became sole owner of this property, and, after living there two years, was killed by the Indians in a battle at the mouth of Butte Creek. He was leading a company of volunteers, and while charging in the brush was pierced through the body by an arrow from an Indian bow. The Indian was lying on his back and sprang his bow with his feet--a very effectual way, as great force can thus be given to the bow to speed the arrow. George E. Cole, Early Oregon: Jottings of Personal Recollections of a Pioneer of 1850, 1905, pages 48-63 Southern Oregon Pioneer Association Records, Resolution on Deaths of Members, volume 2, page 4, 1892, Southern Oregon Historical Society MS 517 On the first Sunday in June, 1853, [George E. Cole], with Major Lupton, rode into an Indian ambush a few miles above Table Rock, which proved to be Cut-Face Jack's wild band of Upper Rogue Rivers. Having met the redoubtable chief on a former occasion, by dint of good talking--i.e., by satisfying Jack that they were not the "Bostons'' he wanted--they were permitted to continue on their journey to Jacksonville, their point of destination. Julian Hawthorne, ed., History of Washington, Vol. I, New York 1893, page 365 James A. Lupton, 28 1854 Jackson County census Jackson

Co. O.T.

Dear Sister,July 3rd of 54 I received your [letter] a few days ago, and was glad to hear from you. You told me that you had heard from sister Elizabeth but did not tell me where abouts in New Jersey she was. If I knowed where she was I should write her. I have received four or five letters from you since last fall, and have answered them partly--I am living on a farm and have been for the last year. I am making a living, and that is about all. I had in a fair crop this year, but it will not be more than half a crop at last. I had thought of coming (I was going to say home!!) to St. Charles this coming year, but I shall not be able. Times have been very hard in this section of country the last year, but I think will improve in a short time. This is the first year there has been any wheat raised for market. There will be considerable for sale this fall. There is a great deal of money taken out of the mines in this vicinity, [but] at the same time it has been taken out of the country. Consequently, not much of it [is] in circulation in this valley. Next year we'll be able to raise as much wheat as will be consumed at home and be able to keep a large amount of money in circulation, which we now send off in exchange for flour-- This valley is rich in soil and the hills and mountains around it is rich in mineral wealth--new diggins in several places have been discovered in the vicinity of this valley within the last month, which are said to be very rich. The country in this vicinity is not half prospected as yet, and I am inclined to believe there will be new diggins discovered for many years to come. This is truly a golden country--still there is here [nothing] but the glittering dust to keep me. Society is very poor indeed. Families that were not second-rate in the States are here set up as the bong tong, and are considered the upper "Ten." You can see young ladies put on all the airs (which they are by no means master of) which would lead a person to believe they were accomplished and polished ladies, but when examined they are of the very coarsest texture. Their manners are coarse and blunt, and all they can say is yes or no. The young men are of a better class. This country is one of the best places in [the] world for ascertaining what a man is. A man who has been in this country for the term of three years and has not made anything, you can put him down as not fit for anything. There may be exceptions, but very few. Industry and economy, with a tolerable share of good health and a moderate share of good luck in the course of three years will place a man in very easy circumstances. I

am

Southern Oregon Historical

Society MS 377Your affectionate brother J. A. Lupton Jackson

Co. O.T.

Dear SisterFebr. 30 of 55 I received your letter a few days ago, the date of which I have now forgot. I was very glad to hear from you and shall be happy to hear often of you and your family. I am a very poor hand to write. I would much rather receive than write letters; at the same time I will endeavor to write oftener. I receive occasionally a newspaper, for which I am very much obliged to you for, and shall send some in exchange. I was very sorry to hear of the situation [of] Sister Elizabeth. She is certainly an object of pity. I feel sorry from the very bottom of my heart for her. I should be very glad to have her with me, and if I could find out where she lives I would write her, and if she desired to come and live with me I would assist her in getting to this place. I am very sorry to hear that your patience is exhausted with her. You should remember that she has not been so fortunate as ourselves. She is a poor, unfortunate woman and deserves our sympathy. She has not the knowledge that will enable her to overcome and bear with patience the many trials and difficulties which she has to encounter. She may have got a worthless husband, and if so he will not provide for her as abundantly as he should. To be neglected by a husband is something very trying; to be alone in this world without anyone to advise with or protect us is very bad, but to have one whom we depend upon and placed all our affections with the expectation of meeting with a reciprocal feeling and then to be neglected and disappointed is something truly trying and mortifying. Such a one truly deserves our sympathy. I hope you will bear with patience the trouble she may give you. I have not had a letter from her at all, but would be very glad to have a communication from her so that I might know where to write to her. I would do so often, and shall write her at Washington City. I hope you will write her often and console her as much as possible. I should like very much to have John here with me. As to poor Father, I presume he is dead. It cannot be possible he is alive at this time. It would give me a great deal of pleasure to have seen him once more, but it cannot be possible in the ordinary course of events that he is alive at this present time, and [I] therefore will never enjoy the pleasure of seeing him again. When I think how we all have been separated from one another almost from infancy, I cannot help shedding tears. I am so completely overcome that I am compelled to stop--I could weep for days if it would alter the matter any. There are persons in the house [i.e., he is not alone as he writes] and I feel ashamed. I could not control my feelings. But when in imagination I contemplate a family reared among strangers, without anyone to guide, direct and assist them, depending altogether upon the kindness of strangers [against] "the cold mercy of the world," I seem to contemplate one which should excite the sympathy of all kind and generous hearts. I cannot think about it without being so overcome as to feel my heart ready to burst. You that is blessed with a family, remember the great responsibility that rests upon you; raise your children in the fear and love of God, and they will love and respect you. Be careful of their education. Give them an early education and give them a good one. It will be a passport for them through life, an introduction to society; it will be a source of consolation in the hour of adversity, a solace in trouble; with a good education they will be able to wend their way through life in a manner that will do honor to their parents and credit to themselves. Their careers in after days depend wholly upon the principles you instill into their youthful minds. Therefore you cannot be too careful. Treat them kindly; you do not know how soon you may be taken from them, and they left to battle with the storms and difficulties that beset their path through life. God grant that you and your husband may live long to enjoy the happiness which your children will afford you, a blessing which I most sincerely wish both of you. I do not belong to that fortunate portion of the human family who has a companion who can cheer him in the hour of adversity or share his prosperity. I have no one to disclose my secrets to, no one to cheer me in the hour of despondency, no one to smooth my fevered brow on the couch of sickness, no one to lament my absence, or to smile at my return, no one to give me those heaven-born smiles which should make a man feel his greatness and cheer him on in the paths of rectitude and moral worth. This is a blessing which I do not enjoy. You spoke to me of one Miss Powell, or at least of a lady you thought would suit me. I am afraid you do not know what my ideas are of a lady or what constitutes a lady. My notion about women has changed considerable since I came to this country. I find but few ladies in this country but what are destitute of those qualities which I think are requisite to make a lady, and I am beginning to think that ladies are scarce in every country. I do not think I shall be able to go and see you for a year or two. I intend to leave just as soon as I can get my business in a condition so that I can do so. Times are very hard at present in this country, as well as in the States, owing to a dry winter. The miners have been in want of water all winter. Times would be very good if we had plenty of water. There is hardly enough of money in the country for common business purposes. They still continue to discover new mines. The late discoveries are very rich. I forgot to tell you what kind of a lady would suit me. I want an intelligent, well-polished, refined in manners, fine education, a fine signer, plays well on the piano and other instruments, a good, amiable disposition, kind and affectionate, one who would make a home happy, one who would appear well in society. This is the kind I want, none other will suit. Write soon, and if you can find out any about Father, John or Elizabeth let me know it all. Give Mr. Holmes my best regards. I

am very respectfully

To Mrs. M. HolmesYour affectionate brother J. A. Lupton Southern Oregon Historical Society MS 377 1855 Apr 25 Wednesday. We plowed for corn. Mr Rockfellow's Mule took sick and he brought it up for Father to cure. It is some better this evening. Major Lupton came to visit us this evening he is going to stay all night. 1855 Apr 26 Thursday. the Major stayed all night. We plowed for corn. It has been a fine day Diary of Welborn Beeson Dear Sister, I received your letter of August 6 inst. I am very glad to hear from you, and also from Elizabeth. At the same time, I am very sorry to hear of her misfortune. You informed me that she was in Potts [sic] County, Pennsylvania, but I am at a loss to know at what particular place. I will write her immediately but when you write me again, you will please inform me at what place in Potts County, so that I may be enabled to send directly to her. I am pleased to hear that your family are all well, but you discourage me very much when you say that you know quite a number of polished ladies, and that I cannot get any of them. I sent Mr. Holmes a number of newspapers. If you have seen them, and have examined them closely you will perceive the position I occupy before my countrymen, and if the position I [omission] is worth nothing, then I am not entitled to a polished lady. You will perceive by examining those papers that I am a member of the Legislature of this Territory, and when we consider that there is as much talent in this county as there is in the county of St. Charles, and having it arrayed against me in my election, there is a strong probability that I occupy an honorable position before my fellow countrymen. And if so am I not entitled to an accomplished companion. If I am not, then there is no use in one spending half of the nights in endeavoring to acquire knowledge or of acting honorably with my fellow man--one thing certain, when I marry, I shall marry none but her who I think will be intelligent enough to appreciate true worth. I do not think any the less of a person because they are not accomplished, or because they do not suit me--but I do not place my affection on them. I have seen many a lady who would make a man an affectionate wife, and who were worthy of a man who possesses those qualities which go to make a great and good man. Yet they did not suit me. If you could see some letters which I have received from a lady in St. Louis, you would think I am not forgotten and also that I know some who possess the elements of a refined and polished lady--if you think that I would suit the Polish lady which you speak of, you may say to her that I intend returning in a short time if not sooner, and if she cannot do any better, she had better wait and try her luck. I am rather partial to the Poles, and especially for those Polanders who endeavored to cast off the yoke of oppression and elevate themselves and their country to that proud position which the God of nature intended they should occupy--my heart beats with love for that country which adopted those glorious principles of human rights that we find in the Polish constitution-- I

am your affectionate brother

Southern

Oregon Historical Society MS 377 Written shortly before

Lupton's death

on October 8, 1855. He had been elected to the Legislature on June 4.J. A. Lupton From Southern Oregon.

Forest Dale,

Jackson County,

Editor of the Oregonian:--I

have but little news to send you this week. The trial of Oldham for the

murder of Dr. Alexander is over, and has resulted in an acquittal.

There has been another stampede of Indians from the reserve, and the

troops are in the field endeavoring to persuade their naughty pets to

return to their friends, in order that the "fatted calf" may be killed,

and that there may be much rejoicing thereat.Southern Oregon, Aug. 25, 1855. The Indians engaged in the late bloody tragedy on the Klamath are still at large, and the probability is that they will be suffered to go unpunished, unless the citizens of northern California shall rise in their might and with their own hands inflict the punishment these "red devils" so richly deserve. Thousands of dollars have already been expended by her citizens in an honest endeavor to avenge the death of so many of their friends and comrades; they traced the perpetrators of these foul deeds through the mountains to the reserve in this valley, whither the guilty had fled for protection, which was immediately offered them by the military at Fort Lane, and, as a matter of course, the pursuing party was compelled to return without having accomplished their designs. In the event, however, that the Indians are not soon given up, the volunteers who enlisted in this cause at the commencement will return with the requisite reinforcement, and will, with renewed vigor, prosecute the object of their mission to the bitter end, and, if necessary, assistance will be rendered them by citizens of this valley, notwithstanding we are compelled in a measure to obey the mandates of "a secret political organization" known as "Durhams," whose chief has proclaimed to the world that no expedition against their particular favorites--the Indians--shall receive the sanction of his office, or, in other words, the sanction of the executive of this Territory. Those of our citizens who are so often compelled to act on the defensive, and to make the rifle their constant companion, who have lost relatives and friends, and perhaps the fruits of years of toil, can best judge of the position in which we are placed by such manifestations on the part of those in power in Oregon. The same line of policy should be adopted here with regard to Indians that is pursued by our companions on the other side of the Siskiyou--viz.: to commence a war of extermination, which would at once compel the military to keep the Indians garrisoned, and if the government is particularly desirous of propagating the species, would also compel them to furnish the Indians such nourishment as in such cases is required. Note--Since writing the above, information has arrived that the Indians have robbed several houses on Applegate Creek, twelve miles from Jacksonville. Oregonian, Portland, September 8, 1855, page 2

I approve [of] your course in not consenting to

surrender those Indians into the hands of the "volunteers." The laws of

the country clearly indicate a different mode of disposing of such

cases. Besides, some of those suspected may not be guilty, and their

delivery into the hands of a mob (and such I apprehend the "volunteers"

were in the view of the law) would have been equivalent to shooting

them down. If the perpetrators of the atrocious deed, they deserve

death, but an excited and enraged population are illy qualified to

discriminate between the innocent and the guilty, and however deserved

the punishment, all experience proves that executions without the forms

of law are not only without salutary effect, but of [a] positively

injurious tendency.

It cannot be too strongly impressed upon the Indians that their only security against violence and wrong from reckless whites is to remain quietly on the reservation, that if they leave it and mingle with the vagabond Indians infesting the region adjacent to the boundary between Oregon and California, or at any time give countenance and protection to any fleeing to the reservation to escape detection and punishment, and that their security, happiness and prosperity as individuals and as a people rests upon their upright and peaceful deportment and prompt surrender of all among them guilty of violence, robbery or theft. Prescient letter of Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer to Rogue River Indian agent George H. Ambrose, September 19, 1855; Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1872, Reel 5; Letter Book D, pages 289-292. It is true Indian difficulties may occur, but in this valley it is not likely without some of us are very anxious for it. During the past six months peace has not been interrupted for one hour in the upper R.R. Valley. One or two men have been killed in the valleys or mountains towards the coast. As many have been killed or wounded in the same time in drunken brawls between whites. Yet during all this time you have labored over the signature of "Clarendon" and otherwise to make the impression that there has been continual skirmishing and fighting with the Indians in Rogue River Valley and "Forest Dale." This is unjustifiable; persons at a distance are deterred from coming to the mines; emigration is turned away in some other direction, and the settlers are kept in a continual alarm and uneasiness. "Anti-Humbug," letter dated September 22, 1855, Oregon Statesman, Corvallis, October 13, 1855, page 1 Letter from the South.

About the middle of the week Major L.

came into town

and addressed the citizens, informing them that it was determined to

organize several companies and attack the Indians at different points,

so that none should escape. He also said that the Indians were in great

commotion at seeing the settlers driving their cattle and moving their

families away from their encampments. "I have been among them," added

the Major, "and pacified them with the assurance that we were not going

to war with them,"

and he then coolly proposed to massacre them while off their guard. . .

.Forest Dale,

Jackson Co., O.T.

Friend Dyer:--I have but little news to send you this week. Business is

somewhat dull, though apparently improving. Farmers are busily engaged

marketing their wheat and other products, and our merchants are laying

in their winter supply of goods. The miners in this vicinity are

preparing for a good winter's work--an abundance of water being

anticipated.Sept. 28th, 1855. Three excellent flouring mills are in active operation in this valley, and a large portion of the flour manufactured is being sent to Yreka and sold or placed in storage. The past has proved an exceedingly prolific harvest, paying but a small remuneration however to the farmer, on account of the low prices for which he is compelled to sell his produce. A young man by the name of Thomas Low, some few days since, caught his foot in the gearing of a threshing machine and so fractured the leg as to render amputation necessary. The operation was performed by Dr. C. B. Brooks of Jacksonville, under whose judicious treatment the patient is doing well. A zealous opposition to the chastisement of Indians who have, and still are, committing depredations upon the citizens of this section of country in the settlements and on the highway is manifest on the part of several official dignitaries residing south of the California mountains, all of whom belong to the Durham herd. It is the opinion here that every one of the correspondents of the Oregon Statesman, and its echo the Umpqua Gazette, aside from the conductors of those sheets, are office holders. Such being the case, it seems to be a candid observer that no other evidence is required to establish the fact that a mutual sympathy does exist between the Indians here and the so-called Democracy of this Territory, especially as these communications have been freely endorsed by the leading stars of that secret political organization, known as the Salem clique. To the impartial reader, however, let these matters be submitted; one thing is certain, that the depredations which the Indians are constantly committing has created a violent antipathy against the entire Indian race in the minds of the majority of the citizens of both Southern Oregon and Northern California which cannot easily be eradicated, and these feelings are kept alive by the Indians visiting, whenever their own safety will admit it, the relatives of those who have suffered from their hostilities, and boasting of the tortures they have inflicted on their relatives and friends. Notwithstanding the oft-repeated declarations made by the Indian sympathizers, as heralded forth to the world through their hireling presses, that the utmost harmony exists between the two races, a system of warfare has been carried on by the Indians here that has within the last five months in this section of country alone brought no lesser number than twenty-two of our citizens to an untimely grave. To make up this number I am compelled to note the massacres which have occurred during the present week. On Tuesday last, as a small party of men with teams were crossing the Siskiyou Mountain on the road to Yreka, they were attacked by Indians, and two of their number, Calvin Field and John Cunningham, killed. The Indians also killed thirteen head of oxen on the spot, drove off several more, and carried away a considerable quantity of merchandise. This was not enough, however, to satisfy their savage thirst for blood, for on the following day they succeeded in killing another citizen, making the third [death], and wounding the fourth. Who is to be the next victim time alone can tell; occurrences of this kind have become so numerous within the past few months that I cannot but believe that the extirpation of every Indian tribe infesting this section of country particularly is a sacrifice due to the glory of God and the security of the lives and property of our citizens. CLARENDON.

Oregonian,

Portland, October 13, 1855, page 2From the Crescent City Herald,

Oct., 1855.

An Indian war in Rogue River Valley is now on. A volunteer force of one

hundred or one hundred and twenty-five men had been formed, and after

having completed their arrangements they proceeded on Sunday evening,

the 7th inst., to the mouth of Butte Creek in the vicinity of Fort Lane

in several parties, according to the number of rancherias, and

commanded respectively by Major Lupton, 36 men, Capt. Williams 14,

Messrs. Bruce, Miller and Hayes 11 each, Mr. Harris 18 and Mr. Newcomb

17 men. Early on Monday morning the volunteers approached the

rancherias, and the Indians first fired upon Harris' command. The fight

then became general and ended in the total defeat of the Indians, 30 of

whom, left dead on the ground, were afterwards buried by the military

from Fort Lane. Of the volunteers, 12 men were wounded; one of their

number, Major Lupton, who had received an arrow in the left breast,

died on Monday night, and another named Sheppard, wounded in the

abdomen, it is thought will not recover.Del Norte Record, Crescent City, May 20, 1893, page 1 Startling News from Rogue River.

Mr. Eber

Emery, from Rogue River Valley, has furnished us the following

startling news from the north:A party of the citizens of of Rogue River Valley, who were on the hunt for the perpetrators of the late murders on the Siskiyou Mountain, found the trail of the Indians near the scene of that bloody tragedy, and followed it across the mountains to the head of Butte Creek, a tributary of Rogue River. They then returned to the valley, procured reinforcements, and started up Butte Creek. On Saturday night, 6th inst., they came upon a large party of Indians. They came to the conclusion that the murderers were among them, and we think the conclusion a reasonable one, and that this party was there on purpose to cover the return of the murderers to the Indian Reserve at Fort Lane. The Indians were surrounded in the night, with the intention of showing them no quarter in the morning. But when daylight came, it was found that they had escaped to the Reserve. They were followed thither and again surrounded on Sunday night, and on Monday morning at daylight a deadly fire was opened upon them killing about thirty Indians, together with a few of their squaws and children. Ten whites were wounded, all slightly with the exception of Maj. J. A. Lupton, whose wounds are thought to be dangerous. Marysville Herald, Marysville, California, October 16, 1855, page 2 This is a confabulation of the tracking after the Siskiyou Massacre with the Lupton Massacre. It fails to point out that two weeks passed while the party "procured reinforcements." For

the Oregonian.

Letter from the South. Forest

Dale, Jackson Co., O.T.

Editor Oregonian.--Rogue

River Valley is again reaping the benefit arising from imported

sympathy for the "poor Indian."October 6th, 1855. The entire community here has become alarmed, and if coming events ever cast their shadows before them, then we are to have a second edition of the war of '53 and the predictions of many of our citizens fully realized. Many of the residents here are removing their families to places of safety, and are shouldering their rifles in defense of their inalienable rights--the peaceful possession of homes and firesides; even men who have heretofore sustained the policy pursued by those having authority in this Territory, with regard to Indian affairs in Southern Oregon particularly--and who have ever been on the alert to mislead the public mind relative to the many expeditions and engagements of which the Indians here have been productive--and who have even come so far as to prefer false charges against men who have taken an active part in such expeditions and engagements, have signified a willingness to espouse the cause of the white man by taking up arms against the very beings (if beings they are) whose virtue, honor, integrity and loving kindness have ever been the burden of their songs--the objects of their happiest dreams. Since the massacre of Fields, Cunningham and Warner on the 25th of September just past, I have received no positive information of the loss of any more lives, although report says that fifteen men have just been killed on Beaver Creek, on the opposite side of the Siskiyou Mountains. This does not seem incredible, as it is known that a large number of Indians are prowling about in that vicinity. On Thursday last, a party of Indians fired upon Mr. Myers and Mr. Fisk, near the residence of the former and but a short distance from the Eagle Mills, but fortunately missed both of their intended victims. On the same day another party killed several head of cattle at Vannoy's ferry on Rogue River, below the reserve, and on the following day a party of about forty miners [sic] proceeded from the Reserve to the residence of Mr. Decker, near the mouth of Butte Creek, and drove the family from the house; this I think is the third time within the last two months that Mr. Decker and family have been compelled to leave home and seek the more populous section of the settlement for protection against those government pets. On Applegate some stock has been taken, but of the amount I am not advised. Capt. Bob Williams is in that vicinity, and I expect soon to hear of the effects of his unerring rifle. A company of volunteers, under the command of Capt. A. G. Fordyce, is already in pursuit of Indians in the vicinity of Mr. McLaughlin's, and if there is anything in the general appearance of men, this company is bound to render a good account of its stewardship. The supplies for the volunteers already in the field have been raised by contributions; I predict, however, that in the event of a general war, as now seems inevitable, that the procurement of supplies will be almost an impossibility, for the coffers of our citizens have already been drained to such an extent, for like purposes, that they are wholly unable to furnish supplies without a fair remuneration, and it is generally thought that the Governor of Oregon, with his best of advisers, will report against such prices being paid, as they have done in other instances, where volunteer service has been rendered under similar circumstances. In the event that my prediction proves correct, or perhaps if otherwise we might with seeming propriety address the executive of this Territory, in the language of Jefferson to the British king, "open thy breast, sire, to liberal and extended thought." The great principles of right and wrong are legible to every reader, to peruse which requires not the aid of many councilors. If however we are to judge of the future by the past, quotations from their favorite authors will be of no avail. Political supremacy instead of principles of justice has too long been the basis of a great part of the policy pursued by the champions of Durhamism relative to Indian affairs in Southern Oregon. Oregonian, Portland, October 20, 1855, page 2 I found that Mr. Jones was disposed to the shooting plan, for he had been with the Major, and had agreed to go down the Valley and help muster a company to act in concert for a general massacre. I felt impelled to remonstrate against such injustice, and pointed out the probability of himself and some of his neighbors falling in such an encounter. I reminded him that the Indians were not only more numerous than ourselves, but that they occupied vantage ground, that when attacked above, they would naturally run down the valley and kill all before them. I begged him to remember that it is not Indian nature, but human nature, to make a desperate struggle, rather than give up life and home. But Mr. Jones mounted his horse and rode away, apparently fixed in his determination for slaughter. . . . I did not know what further measures had been taken until Sunday morning, when I was informed that a meeting of citizens had been held, that two Methodist preachers, and other leading men, had made speeches, and that the unanimous feeling was in favor of the measures which have already been set forth. Monday morning, October 8th, 1855, was the time agreed on to commence the work. As there was a Methodist quarterly meeting to assemble that day, within two hours' ride of the scene of the intended massacre, I hoped there would be heard in that religious assembly some expression of brotherly kindness and charity for the poor doomed outcasts in their immediate vicinity. Full of this hope I attended the meeting, but the services progressed with the rehearsal of "experiences" common on such occasions, until speakers became scarce, and the presiding elder exhorted all who had anything to say for the Lord to improve the time. I arose, and spoke with all the feeling, and all the power I had, in the behalf of the poor Indians. I entreated that assembly, who had gathered themselves together in the name of Christ, whose whole life and ministry was a living Gospel of Love, to put on the spirit and the power of Christ. I begged them, by every principle of humanity and justice, to inflict no wrong upon the helpless. I drew in strong colors the scenes that would inevitably follow such an attack as was meditated. I thought if there was a soul, or a heart in them, I would find it, even if it could be reached through nothing but their own selfishness. I pictured our burning houses, our murdered wives and children, our silent and desolated homes, and all the wrongs that would inevitably flow into that crimson: torrent they were about to open. In conclusion, I strongly urged them, as citizens and Christians, to raise a voice of remonstrance, or to call on the authorities for the administration of justice, and thus avert the impending calamity. No voice responded to the appeal, and the meeting closed, for no one had independence enough to speak his thoughts. But I afterward learned that there were members of that assembly who silently acknowledged its force, but the pressure of public opinion prevented open expression. I cannot resist the conviction that if the presiding elder, with his brethren of the ministry, and leading members of the Church, had taken a firm, manly, and Christian position, as advocates of the Gospel of Peace, the horrors of that week, and of the subsequent war, might have been prevented. I am confirmed in this opinion by one who became penitent for the part he had taken in those atrocities. He solemnly declared that he was led into it by the preachers. . . . During the following week all was intense excitement through the length and breadth of the valley, but the prevailing hope was, that, as the work had commenced, it would be effectual, and soon accomplished. Numerous were the reports as to individual cases, as well as the general progress of the enterprise, and it was difficult to obtain the exact details. The following is as near the truth as I could ascertain. During the night of Sunday, the main body of the assailants approached as near to the Indians, on or near the Reserve, as they could without being perceived. They were found in several ranches on the banks of the river. Three companies crept on their hands and knees through the chaparral, so as to obtain advantageous positions. With the first early dawn of morning they poured the deadly contents of their rifles through the frail tenements, under which were sleeping helpless men and women, little children, and nursing infants. Let fathers and mothers fancy themselves and their sleeping babes thus assailed, and they will realize better than I can describe the horrors of that occasion. Being thus unprepared for war, and taken by surprise, the Indians fled for shelter to the surrounding chaparral, while their assailants continued, with their revolvers, to dispatch all they could reach. They captured two or three Indian women alive, and when no man was in sight, it being something of a risk to creep after them in the brush, these women were compelled, under threats of instant death, to force out their husbands and sons and brothers, that they might be shot without danger to their destroyers. It was while thus employed that Major L., already spoken of, received an arrow from an unseen hand, which penetrated his lungs, and he fell. One of his companions was also mortally wounded by an arrow, and both of them died in the course of two or three days. Several others were slightly wounded, and thus their cowardly and outrageous proceedings were, for the time, suspended, if we except the amusement of stabbing and target-shooting at the bodies of the dead that were left on the ground. I never ascertained how it was that on this occasion the Indians used only bows and arrows. It must have been that some strategy had been used to get possession of their guns, or else they had not time to load them, for in the various reports of this affair, firearms were not mentioned in my hearing. Fort Lane, commanded by Captain Smith, was within a short distance. I cannot think of this officer but with feelings of profound respect. His proximity to the Indians, and frequent intercourse with their chiefs, afforded him facilities for knowing the nature and extent of their grievances. With the heroism of a soldier, and the magnanimity of a true man, he steadily, and to the utmost of the means at his command, resisted the popular torrent, and nobly pledged his life in protection of the weak and the defenseless. A detachment was sent from the fort to bury the dead. They reported having found twenty-eight bodies, fourteen being those of women and children. But as many dead were undoubtedly left in the thickets, and no account was taken of the wounded, many of whom would die, or of the bodies that were afterward seen floating in the river, the above must be far short of the number actually killed. Of those that escaped, eighty were received into the fort, and had there been provision, and men enough for defense, more would have been admitted. For thus leaning favorably toward the poor fugitives from slaughter, the most bitter denunciations were poured upon the head of the Captain, and for many months his name was often coupled with the most ignominious and degrading epithets. John Beeson, A Plea for the Indians, 1857, pages 46-48, 50-51. According to Beeson, Jones is the same man killed the next day at Bloody Run (page 51). GENERAL

ORDER No. 10.

Information having been received that armed parties have taken the

field in Southern Oregon, with the avowed purpose of waging a war of

extermination against the Indians in that section of the Territory and

have slaughtered, without respect to age or sex, a friendly band of

Indians upon their reservation, in despite of the authority of the

Indian agent :and the commanding officer of the United States troops

stationed there, and contrary to the peace of the Territory, it is

therefore ordered that the commanding officer of the battalion

authorized by the proclamation of the' governor of the 16th day of

October, instant, will enforce the disbanding of all armed parties not

duly enrolled into the service of the Territory by virtue of said

proclamation.TERRITORY

OF OREGON,

Headquarters, Portland, October 20, 1855. The force called into service for the suppression of Indian hostilities in the Rogue River and Umpqua valleys, and chastisement of the hostile party of Shasta, Rogue River and other Indians now menacing the settlements in Southern Oregon, is deemed entirely adequate to achieve the object of the campaign; and the utmost confidence is reposed in the citizens of that part of, the Territory that they will support and maintain the authority of the executive by cordially cooperating with the commanding officers of the territorial forces, the commanding officers of the United States troops, and the special agents of the Indian Department in Oregon. A partisan warfare against any bands of Indians within our borders or on our frontiers is pregnant only with mischief, and will be viewed with a distrust and disapprobation by every citizen who values the peace and good order of the settlements, It will receive no countenance or support from the executive authority of the Territory. By the governor: E.

M. BARNUM,

Ex.

Doc. 76, 34th Congress, 3rd session,

1857, pages 156-157Adjutant General. About thirty-two years ago, while the subscriber was on the jury during court week at Jacksonville, Oregon, a man came into the room and said: "There is a camp of redskins below here. I have put them off their guard by assuring them that the whites want peace and will not again disturb them. "Now I propose that we organize three companies to surround them and make a clean finish of the whole lot at once." A Methodist quarterly meeting was held on the day before the contemplated massacre, Elder Wilbur presided; an appeal to the moral sense of the people was made during the love feast in behalf of the Indians, which had such an effect upon Elder Wilbur that he could not rest until he got the appointment of an Indian Agency, which he held with honor and great usefulness for nearly thirty years. In answer to a letter from him I went to Salem last December. But I was too late, for I met this funeral procession in the street, and I only saw his good old face as I stood by his coffin in the church. John Beeson, "Old Events and Recent Occurrences," The Better Way, Cincinnati, May 19, 1888, page 2 There are near thirty or forty volunteers camped on Butte Creek, in search of the Indians that killed those men on the Siskiyou. They are under the impression that the Indians on the reservation are connected with that transaction, which I do not believe. I have seen no cause to alter my mind as to who committed that act. I believe it to have been done by that remnant of "Tipsu Tyee's" people, who are yet living in connection with some Shastas. When this war excitement shall have subsided a little, which I trust will be the case shortly, I will furnish you statements of what is transpiring by my mail. Letter of G. H. Ambrose to Joel Palmer, October 8, 1855; Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 13; Letters Received, 1855, No. 89 A correspondent writing from Lower Rogue River, under date of Oct. 8th, informs us that he had received news of the massacre of two white men near Wait's mill by the Indians. They also set fire to a house on Butte Creek, which was entirely consumed. Let these inhuman wretches beware of the speedy punishment which is sure to follow their fiendish depredations. The people of Southern Oregon have remained quiet under these outrages until forbearance has ceased to be a virtue, and they are now arming themselves for the purpose of giving the perpetrators the chastisement they so richly deserve. Oregonian, Portland, October 20, 1855, page 2 A battle was fought at the Buttes by the Jacksonville volunteers, in which 41 Indians were killed, and two of our men killed and nine more wounded. This was on Monday. A. G. Henry, letter of October 12, Oregon Statesman, Corvallis, October 20, 1855, page 2 Before leaving Willamette Valley old residents of the country remarked the smokiness of the atmosphere, telling us it was less smoky in 1853, when the Rogue River war was in progress. They said the mountain atmosphere was very clear when there were no fires in the mountains, and that these fires were kindled by the Indians as war signals, and they feared a general outbreak. But all seemed quiet as we passed on through the Umpqua and out by the cañon--which would be a terrible place to encounter a band of desperate red men, it being the worst pass for a wagon road I ever saw--and on through Rogue River Valley. Yet the people were apprehensive of danger as we neared Jacksonville, for the report of the attack on wagoners in California, near the Oregon line, had reached the valley, and the memory of 1853 revived. At Jacksonville the excitement was intense. The report was believed that Gen. Wool had come up from California for the purpose of prosecuting the war; that he had recommended the organization of volunteer companies, and given the soldiers at Fort Lane permission to volunteer, which they had immediately done to the number of sixty, under command of Col. Alston. At Sterling, the same day, Sunday, Oct. 7, a volunteer company was made up under command of Smiley Harris, and I came to Jacksonville toward evening. They were to meet a company from Bear River, and another from Butte Creek, and before morning attack on Butte Creek some of John's Indians--about twelve in number--who, with others to the number of twenty-five, had been stopping several days in the same place, and could be easily surrounded and cut off. John's men had long been lawless, and it was hoped they would now be destroyed. We breakfasted on Monday at Fort Lane, after a ten miles' morning ride from Jacksonville, and then learned that General Wool was not there, nor was he expected; that the volunteer companies were not authorized by the officers at the fort, and the soldiers were all there--two companies, one hundred and fourteen each. Capt. Smith, our host, pointed to eight or ten Indian women and children, who had come to the fort for protection about daybreak. The men at the fort had heard firing a little while before, and soon learned that the volunteer companies had not found the company of John's tribe, as they expected, for John's men had heard of the intended attack and gone off upon the reservation. The volunteers then went to a rancheria, containing at the time two men, and women and children to make up a dozen, fired into it, killing one old woman and slightly wounding another. [The actual toll of the Lupton massacre was much higher.] The woman killed was Sam's mother, and the company were Sam's Indians. This Sam was chief of perhaps a hundred men, whom the Shasta Indians had long tried to induce to join them against the whites, but Sam had hitherto refused. Whether this outrage would induce him to turn, Capt. Smith did not know. He thought whatever lawlessness the Indians committed, the whites were the aggressors, as in this instance. He said if John's men had been cut off it would have been unjust, for they had been peaceably fishing and drying salmon for several days, and he did not think they had hostile intentions. Sarah Pellet, letter of October 15, 1855, in New York Daily Tribune, November 14, 1855, page 6 Office

Indian Agent,

Sir--Whilst

engaged in writing you a few lines yesterday morning, I received a

message from Capt. Smith, informing me that the volunteers had made a

descent upon a small band of Indians, camped about two miles from Fort

Lane, in which several Indians were killed. I immediately repaired to

the scene of action and found that Sambo's band of Indians had been

attacked just at the break of day, simultaneous with an attack upon

Jake's people, who were camped about one-half mile above Thompson's

ferry (better known to you by the name of Camp Alden), on the bank of

the river. Capt. Smith sent a detachment of dragoons to inform

themselves of the nature of the difficulties, and to see what had been

done; upon arriving at Sambo's camp were found two dead women; one had

died a natural death, and one had recently been shot. I learned from

Sambo that one woman was slightly wounded, and that two boys had been

wounded, each shot in the arm. They were all taken to Fort Lane and

provided for.Rogue River Valley, O.T. October 9th, 1855. We then proceeded to Jake's camp, where we found twenty-three dead bodies, and a boy who escaped said he saw two women floating down the river, and it is quite probable several more were killed whose bodies were not found. I had apprehended danger, and had so informed the Indians several days previous, and Capt. Smith had notified the Indians that if they wanted protection they had to come onto the reserve or to Fort Lane. It seems from their statements that they had concluded to go on the reserve, and had accordingly started on Sunday evening, leaving the old men and women behind to follow on Monday. In the meantime this attack was made quite early in the morning, which resulted as above stated. There were found killed eight men, four of whom were very aged, and fifteen women and children, all belonging to Jake's band. The attack was so early in the morning, it is more than probable that the women were indistinguishable from the men. Upon the part of the whites, James Lupton, the captain of the company, received a mortal wound, from the effects of which he has since died, and a young man by the name of Shepherd is supposed to be mortally wounded. Several others slightly. The night following this affair, the Indians rallied together, killed some cattle on Butte Creek, and it is supposed have since joined old man John, who I suppose had been waiting some time for a pretext to commence hostilities, only desiring the assistance of some other Indians, which this unfortunate occurrence secured to him--that of the Butte Creek at any rate--and I apprehend many disaffected Indians will join. On Monday night a young man by the name of Wm. Gwin, in the employ of the Agency, who was engaged at work on the west end of the reserve in company with some Indians, near old John's house, was killed and his body was horribly mutilated, cut across the forehead and face with an ax, apparently as he lay asleep; they then destroyed or took off what provisions and tools that were at camp. They then repaired to Mr. Jewett's ferry, killed one man who was camped at the ferry, and wounded two others. Next I heard of them at Evans' ferry, where they fired at the inmates of the house as they passed, wounding one man, supposed to be mortally. They had with them, at the time they passed, several American horses and mules which they had doubtless stolen the night previous. Mr. Birdseye lost three or four, and Dr. Miller several, Mr. Schieffelin one; they were seen by Mr. Birdseye running some mules off that morning. Old Chief Sam gathered his and Elijah's people together and protected the hands who were employed to work on that part of the reserve, as also the cattle and other property belonging to the Agency. Neither he nor his people want war, nor do I believe they can be made to fight except in self-defense. The whole populace of the country have become enraged, and intense excitement prevails everywhere, and I apprehend it will be useless to try to restrain those Indians in any way, other than to kill them off. Nor do I believe it will be safe for Sam and his people to remain here, if any other disposition can be made of them; it should by all means be attended to immediately. I doubt very much if the military will be able to afford them the requisite protection. Sam entertains the opinion that Jake's people will fight till they are all killed off; John will doubtless do the same. I hardly believe that either Limpy or George desire a war, but have no doubt many of their people will engage with those that do, and possibly they may too. Neither of them or their people are upon the reservation, nor have not been for some weeks, and should either of them be caught sight of, they will most certainly be shot. Taking all circumstances into consideration, I think it hardly possible to avert the most disastrous and terrible war that this country has ever been threatened with. Oct. 10th. Whilst waiting an opportunity to send my former communication, additional news has come to hand. After the wounding of those men at Evans' ferry, the Indians pursued the main traveled road towards the Canyon, where I learned from a company of packers who have just arrived that they saw seven dead men lying in the road in different places between Mr. Evans' ferry and Mr. Wagoner's--several trains had been robbed--and several wagons had been plundered, and I suspect every person who passed the road has been killed. I expect to have to record still sadder news before the week closes. A greater destruction of life will probably never be caused by the same number of people, or more horrid atrocities be perpetrated, than by those Shasta Indians. They are well provided with arms, both guns and revolvers, and skillful in the use of them. I do not believe more desperate or reckless men ever lived upon the earth, and I have no doubt but that they have made up their minds to fight till they die. Very

respectfully yours, &c.,

Gen. Palmer, Sup't. Ind. Affairs,G. H. AMBROSE, Indian Agent. Dayton, O.T. "Rogue River War," Pioneer and Democrat, Olympia, Washington, October 26, 1855, pages 2-3 The original letter can be found on NARA Series M2, Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 13; Letters Received, 1855, No. 93. A transcription can be found in NARA Series M2, Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1872, Reel 5; Letter Book D, pages 323-326. On the morning of the 8th, about thirty Indians, principally old men, squaws and children, were killed while sleeping in their ranches. This preceded the outbreak of the Indians (about 30 hours) and was the immediate cause of it. Lupton was shot in the breast by an arrow in the attack on the ranches on the morning of the 8th. He died of the wound in about two days. He has lately been one of the principal Indian agitators. Letter of October 11, Oregon Statesman, Corvallis, October 27, 1855, page 1 FIGHT WITH THE INDIANS.--A volunteer force of about 125 men proceeded on Sunday evening the 7th inst. to the mouth of Butte Creek, in the vicinity of Fort Lane. Early on Monday morning they approached the rancherias and were fired upon by the Indians. The fight then became general, and 40 of the Indians were killed. Maj. Lupton was killed and 12 of the volunteers wounded. "News from the North," Oregonian, Portland, October 16, 1855, page 1 An Indian War in Rogue

River Valley.

We

are indebted to Mr. Galbraith of the Crescent City Express, for the

following particulars of the opening of an Indian war in Rogue River