|

|

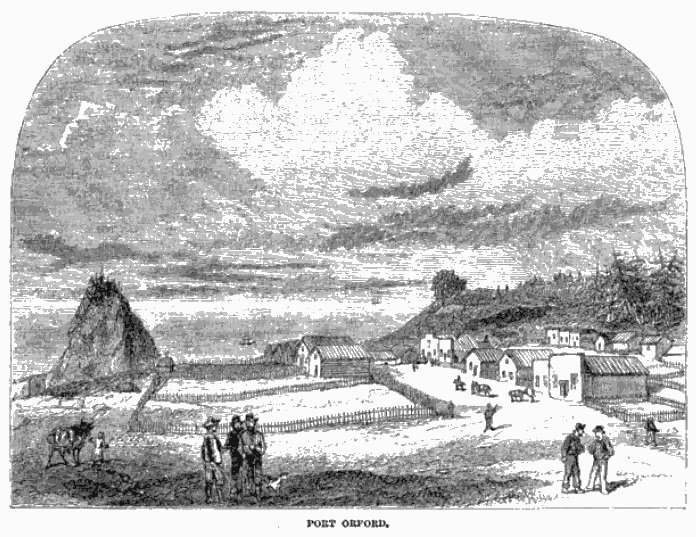

Port Orford 1856 and the massacre at Gold Beach. See also the 1880 account printed in the Marshfield Coast Mail.  October 1856 Harper's Monthly Port

Orford O.T. Oct. 28 1855.

The disturbed state of affairs

in regard to the frequent depredations that are now being committed by

the Indians in Rogue River Valley renders a short communication from

this place necessary. No fears are apprehended, however, from the

Indians in this vicinity, while they are vigilantly watched by our

present efficient and energetic Indian agent, Capt. Benj. Wright, who

is ever watchful and indefatigable in the close observation of the high

responsible duties of his office. The depredations thus far committed

have been all between what is called big bend on Rogue

River and the ferry at the crossing of the Oregon trail leading to

Jacksonville.The Indians living in this vicinity named have declared open war against the whites, and thus far they have killed every white man within their reach. Some friendly Indians who have left the band report something over thirty white men have been murdered, and all their effects have fallen into the hands of the belligerents, comprising animals, gold dust and coin, amounting in all to over one hundred thousand dollars. A company of volunteers is now ready to march from this place, and another from the mouth of Rogue River. The two companies will act in concert with the one from this place. In addition to the white men murdered, a company of Chinamen, numbering seventy men, have also been murdered. More anon. CLINTON.

Daily Alta California, San

Francisco, November 1, 1855, page 1We the undersigned residents of and near the mouth of Rogue River would hereby petition his excellency Geo. L. Curry, the hon. Governor of Oregon Territory, through our representative, William Tichenor, that his excellency would authorize the organization of a volunteer company at the mouth of aforesaid Rogue River and also grant an order for arms of the military post at Port Orford or at any other point at which they can be obtained with facility for a supply of arms for said company. The reasons the undersigned would give for the prayer is that a number of families residing here are compelled to resort to a fort for protection from the hostilities of the Indians above, the murders committed and their defiant threats made and sent to us here, and further, inasmuch as we live in a Territory and a laboring and poor community, think that the government is in duty bound to grant means and facilities for the protection of its citizens, and as many have suffered in the defense of the country also that five or six of our most respectable citizens have within a few days past been massacred (as reported by the Indians). In view of this state of things we humbly pray his excellency the Governor to grant an order in answer to our prayer, and unto whom we will ever be obedient to his orders, and a further request is made to his excellency that "Simon Lundy" be commissioned "Captain," "Enoch Huntley" be commissioned "1st Lieutenant," and "Edward Flaherty" be commissioned "2nd Lieutenant," gentlemen in whom we have full confidence, and a further resolution is that the Captain receipt for all arms so that they may be preserved and subject to the order of the government at any time. Gold

Beach, Mouth of Rogue River, October 30th, 1855.

Oregon State Archives, Military

Records 89A-12, Petitions 1855-1856, folder 29/18 The

signature pages are missing.Gold

Beach Jany. 28 / 56

To

Major ReynoldsChief in Command of Regular Force at Port Orford, O.T. We the undersigned would most respectfully represent to you the deplorable state of most of the residents of this beach, being threatened with an attack by that band of Indians recently encamped at the "Big Meadows." Our best information is that they are between us and the "Great Bend" with the expectation of making an almost immediate attack. We are greatly deficient in guns, so much so that but a small proportion of our numbers are supplied. We have used due diligence through one of our merchants to procure them by sending to San Francisco, but to this time have been unsuccessful. We would therefore very respectfully solicit that you cause to be forwarded to our relief from twenty to thirty guns with cartridges such as you in your judgment think we require.

To his excellency Geo. L. Curry, Governor of the Territory of Oregon The petition of the undersigned residents of and near the mouth of Rogue River, in the County of Curry, respectfully sheweth [sic] that we have been for a long time past menaced by the threatening attitude of the Indians in our vicinity; that we are now for the second time compelled to fortify ourselves for mutual defense; that there are not in this county sufficient arms and ammunition to supply one half of the citizens; that a number of our citizens have been for near three months absent from their homes for the purpose of watching and keeping in check the hostile Indians who are making their way here from the seat of war in Rogue River Valley; that no more men could be spared from here without leaving unprotected the settlement and the families in our midst; that the hostile Indians are fast approaching the Coast with the express determination to exterminate the whites-- And we would further respectfully represent that within a few days past the said hostile Indians did murder two of our citizens who were peaceably passing up the river; and this murder was committed within eighteen miles of the mouth of the river; and we have ascertained that the Indians in our immediate vicinity are aware of the approach of said hostile Indians from Rogue River Valley and prepared to join them. We therefore feeling the responsibility we are under to our country and also to those under our protection, and wishing to meet and punish those hostile Indians who are driven to this side of the mountains by the citizens and soldiers of Rogue River Valley, most respectfully petition your excellency to send us immediate assistance in men, arms and ammunitions. All of which is respectfully submitted. Mouth of Rogue River Jany. 29th 1856 Names

VOLUNTEERS.--For some days past there has been quite an active demand in this city for volunteers to fill up the companies authorized to be raised by Governor Curry. We are told that eight or ten men enlisted with Capt. O'Neil from Althouse. Capt. J. M. Poland of Company K, 2nd Regiment O.M.V., before leaving, requested us to inform persons wishing to join his company to report to him at the camp, mouth of Rogue River, where the company was expected to be mustered into service, perhaps as early as the 22nd inst. Crescent City Herald, February 20, 1856, page 2 (Extracts) Port

Orford, 10 o'clock night

General:February 24th 1856 I have just returned from a meeting of the citizens called together by the startling intelligence from Rogue River. The volunteers, having moved down from the Big Bend, were camped near the spot on which we rested last before leaving the treaty ground--a part of them only were in camp; the balance were at the mouth of Rogue River. At the dawn of day on the 22nd inst. the camp was surprised and every man killed, as now believed, but two, one escaping to the mouth and one to Port Orford on foot through the hills--arriving here tonight. The one who came in (Charles Foster) escaped by crawling into the thicket and there remaining until dark, and there had an opportunity to witness unperceived much that transpired: He states that he saw the Tututnis engaged in it, who sacked their camp. The party were estimated by him to number 300. Ben Wright is supposed--with Capt. Poland and others--to be amongst the killed. Ben and Poland had gone over to Maguire's house (our warehouse). He had word from the Mikonotunnes that the notorious Eneas (half-breed) was at their camp & that they wished him to come and take him away, and he was on that business. Foster distinctly heard the yelling and the conflict of arms in the direction of the house at the time of the attack and murder of the camp. * * * My opinion is that Wright is killed. * * * Every ranch but Lundy's has been sacked and burned, and all still as death. * * * Dr. White saw many of the bodies lying on the beach (bodies of white men) and went by Geisel's ranch and found the house burned and the inhabitants killed. * * * Our town is in the greatest excitement. We are fortifying, and our garrison being too weak to render aid to Rogue River, the major (Reynolds) is making arrangements for protection here, & has sent Tichenor with a request that all abandon R. River and ship to Port Orford. * * * Many strange Indians have made their appearance, well armed, & have actually committed many depredations. * * * We build a fort tomorrow, in which all are engaged in good earnest--all have enrolled themselves for self-protection, and a night patrol is set. * * * Yours in haste R. W. Dunbar. Frames 506-508, National Archives Microfilm Publications Microcopy No. 234 Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs 1824-81, Reel 609 Oregon Superintendency, 1856. Writing from Port Orford in February of 1856, R. W. Dunbar gave a vivid picture of what could happen and what was happening: "I have just returned from a meeting of the citizens called together by the startling intelligence from the Rogue River. The volunteers, having moved down from the Big Bend, were camped near the spot on which we rested last night before leaving the treaty ground. A part of them only were in camp; the balance were at the mouth of the Rogue. At the dawn on the 22nd instant the camp was surprised and every man killed, as now believed, but two. "Every ranch but Sandy's has been sacked and burned, and all still as death. Dr. White saw many of the bodies (of white men) lying on the beach and went by Geisel's ranch and found the house burned and the inhabitants killed. "Our town is in the greatest excitement. We are fortifying, and our garrison being too weak to render aid to Rogue River, Major Reynolds is making arrangements for protection here, and has sent Tichenor with a request that all abandon Rogue River and ship to Port Orford. "We build a fort tomorrow, in which all are engaged in good earnest. All have enrolled themselves for self-protection, and a night patrol is set." Stewart H. Holbrook, "Northwest Hysteria . . . the Indian Wars," Oregonian, Portland, February 21, 1937, page 59 Fort

Orford O.T.

Capt.,February 24th 1856 I have the honor to enclose a copy of a letter this day received from the actg. Indian agent at the mouth of Rogue River, containing information of the outbreak of the lower Rogue River Indians, and the murder of the Indian agent Mr. Wright by the last steamer I notified you of the appearance of the hostile Indians among the tribes bordering on the settlement at the mouth of Rogue River, and that I had sent Lieut. Chandler with the agent to bring down to the mouth of the river, all those who were friendly, which was effected in all apparent good faith on the part of the Indians. Mr. Wright returned about this time and was perfectly satisfied as to the friendly disposition of these Indians and that they seemed [to] adhere to their agreement with Genl. Palmer to move on the Reserve this summer, and I supposed myself that could they be kept from intercourse with the hostile Indians they would remain friendly, and was consequently very anxious to assist Mr. McGuire in effecting this. That the present outbreak is extreme and serious in this quarter there is not the slightest doubt involving all the Indians on Rogue River and some of the coast Indians. One of the men (Mr. Foster) from the scene of the attack has reached this place, and represents the number of persons killed or missing at 21 or 22, and the Indians engaged at between two and three hundred. The following is the list of whites missing from the mouth of Rogue River and vicinity. Benj. Wright, Indian agent, Capt. J. M. Poland, B. Castle, H. Lawrence, E. Nelson, Guy Holcomb, McCluskey, Joseph _____, John Chadwick, _____ missing, Joseph Wagoner, Pat McCulloch, Warner, Mr. Tullus, _____ Seaman, _____ Smith, Geisel and family, _____ Bostman, Jas. Crouch and brothers, _____ Johnson, _____ Martin. I will state that I do not deem it prudent to accede to the request of Mr. McGuire to divide this small command between the two places and wrote to him to say that if they were unable to maintain their position at the mouth of the river, they must concentrate here. We have no animals here fit to move even this small command had it been expedient. I will send a copy of this letter to the comdg. office at Vancouver by the str. as she goes up, also one to Genl. Palmer. I

am sir

To Capt. D. R. JonesVery respectfully your obt. servt. John F. Reynolds Capt. Brvt. Maj. 3 Arty. Comdg. A.A.G. Hd. Qrs. Dep. of the Pacific Benicia Cal. NARA M2, Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 14; Letters Received, 1856, enclosure to No. 89. From our Extra of Monday.

Arrival of the Schooner Gold Beach. Indian Hostilities at the Mouth of Rogue River--The Indians at Gold Beach District in Arms--Their Descent upon the Settlement 4 Miles Above the Mouth--Some 20 of the Settlers and their Families Killed--The South Side of the Settlement in Flames--130 Whites Fortified on the North Side. EXPECTED FIGHT WITH THE INDIANS, NUMBERING OVER 300.

Yesterday (Sunday) morning, as we were favored with the perusal of a

letter written by Robert Smith, a settler up the coast, to Mr. Miller,

living in the neighborhood of Whaleshead, informing the latter that on

the 22nd inst., while Wm. Hensley and Mr. Nolan were driving some

horses towards Rogue River, two shots were fired at them by Pistol

River Indians. Mr. Hensley had two of his fingers shot off, besides

receiving several buckshot wounds in his face. The horses fell into the

hands of the Indians.

The letter contains also a request to urge forward from Crescent City any volunteers that may have been enlisted. ----

From F. H.

Pratt, Esqr., a resident at the mouth of Rogue River, who arrived last

night in the schooner Gold

Beach, we receive the startling news that the Indians in

that district have united with a party of the hostile Indians above and

commenced a war of extermination against the white settlers.The station at Big Bend, some 15 miles up the river, having been abandoned several weeks previous, the Indians made a sudden attack on Saturday morning, Feb. 23rd upon the farms, about four miles above the mouth, where some ten or twelve men of Capt. Poland's company of volunteers were encamped, the remainder of the company being absent, attending a ball on the 22nd, at the mouth of Rogue River. The fight is stated to have lasted nearly the whole of Saturday, and but few of the whites escaped to tell the story. The farmers were all killed. It is supposed there are now about 300 hostile Indians in the field, including those from Grave and Galice Creek and the Big Meadows. They are led by a Canada Indian named Enos, who was formerly a favorite guide for Col. Fremont in his expeditions. LIST

OF KILLED.

Crescent

City Herald, February 27, 1856, page 2

The inhabitants at the mouth of Rogue River have all moved to the north side of the river, where formerly, under the apprehension of a sudden attack, a fort had been erected; they number about 130 men, having less than a hundred guns amongst them. The schooner Gold Beach left yesterday (Sunday) morning at half past five o'clock, and it is supposed that a fight commenced at daylight, as there was a party going to cross to the south side of the river, where they expected to find the whole body of Indians. At sunrise everything on the south side was in flames. The stores of Coburn & Warwick, F. H. Pratt and W. A. Upton were probably all destroyed. Mr. Pratt states that according to the census taken last spring, there are 335 warriors in the district. They were all engaged in the fight, except the Chetcos and Pistol River Indians, who number about 80. The number of Indians from above or out of the district is between 50 and 60. Upon the death of the Sub-Indian Agent, Capt. Ben. Wright, Mr. J. McGuire assumed the duties of Sub-Indian Agent. A boat was dispatched as early as Saturday evening to Port Orford to inform Maj. Reynolds, in command of that post, of the occurrences. As a matter of reference for those not acquainted with the localities, we give the following table of distances up the beach:

Letter from Oregon.

(Through the kindness of one of our patrons, we are permitted to copy the following letter from his brother in Oregon.) Fort Orford, O.T.,

Feb. 29, 1856.

Dear Brother:--In my last letter I

expressed our

fears of an Indian outbreak in this district unless reinforcements

arrived so as to enable us to keep the friendly and hostile Indians

separated. The former were induced to move further down the river,

whence it was intended to remove them to the Indian reserve set apart

for that purpose, as soon as possible. And they expressed their perfect

willingness to go. The hostile bands retired, with their women and

children, up the Illinois, a tributary of Rogue River, and we hoped

that ere they were prepared to make a descent on this district, we

should be sufficiently reinforced to repel them.Captain Poland, whom I spoke of in my last as having assisted Lieut. Chandler of Fort Orford in bringing down the Big Bend Indians, was authorized by the Governor to organize his company and fill it up to 60 men. This he was endeavoring to do, his headquarters being within four miles of the mouth of Rogue River, where all the settlers of the southern part of the district had concentrated. In consequence of the excitement in the northern part of the district, the detachment of regulars were obliged to leave the mouth of Rogue River to the charge of Capt. Poland's company and our excellent Indian agent, Ben Wright. We of course placed little reliance upon the professions of the Indians in that neighborhood, unless we could get the anticipated reinforcements. But [we] were not prepared for the enormity of their treachery as developed on the evening of the 22nd and morning of the 23rd inst. when the volunteers and straggling settlers near the mouth of Rogue River were fallen upon by the Indians of that neighborhood, assisted by the hostile bands from above, and, so far as heard from, 26 men killed. At a ranch half way between this and Rogue River were four men; two of these were killed, the others made a most marvelous escape, one reaching the settlers' fort at the mouth of the river, and the other this place. These two, and one of the volunteers, are all of those attacked who escaped being killed. Among the missing are Capt. Poland and the Indian agent, Ben Wright--two of the best and bravest men in the country. Poor. W. has died a martyr in his untiring efforts to keep peace among the Indians--and has always treated them justly. But the savage, when aroused, knows no mercy--and deep, hellish revenge and treachery are the motive powers of all their actions. The scenes of the last week are enough to erase every spark of sympathy for the Indian race from the bosoms of honorable men. For the last few days we have been in hourly expectation of an attack on this place and the mouth of Rogue River, for the Indians have an idea that if they can wipe out the few settlers and troops at these two points, it will rid this section of the palefaces altogether. All communication by land between the two places is cut off. But yesterday, ten men left in a rowboat for Rogue River, and we will probably hear from them today. I would add that about two-thirds of the Indians of this district have already joined the enemy, and the others will do so also, unless Col. Wright sends us reinforcements from upper Oregon. We are cut off from all communication from other settlements, except by the mail steamer, which is due here every two weeks, but rarely stops in winter. She passed here day before yesterday on her upward trip, and would not have stopped had she not caught fire and been compelled to make this as the nearest port. It served her right. I wish she would catch fire every time she neglects touching here when the weather is so favorable. The Indians are led by Aeneas, a Canadian Indian who, from his constant association with the army and emigrants as guide, is thoroughly acquainted with all our habits and with every part of this country. Before it was known that he had turned traitor, he had succeeded in obtaining large quantities of ammunition from the merchants at the mouth of Rogue River, under the pretense of carrying it to the troops at Big Bend. He was with those men who were killed a few weeks ago, and pretended to have made a narrow escape, whereas he was the accomplice in their massacre. By the late massacre the enemy obtained some 35 guns. They are consequently better armed than the whites. We have everything to fear from this demon. And he has probably already attacked the fort at the mouth of Rogue River. For all yesterday and today, dark columns of smoke have been seen rising up to heaven--showing that the savage torch is at work. Through a spyglass the fort can still be seen standing. As there are about a hundred men in it, they will probably hold out until the arrival of reinforcements. It is impossible for us to succor them, as our force consists of only thirty-odd men, who will have enough to do in keeping the enemy from the large supply of commissary and ordnance stores at this place, also to protect the distressed citizens now concentrated at Port Orford, who are much fewer in number than those at Rogue River. You may rest assured we are constantly on the qui vive, especially as the enemy can approach to our very doors unperceived, through the thick forest that bounds our fort on the north and east. In a few days, however, we will have some of this dense growth down, and will be able to give Mr. Redskin a warm reception. March 1st.

Two brave fellows managed to reach here

this morning

from Rogue River. They represent things there to be in fully as bad a

condition as anticipated. The Indians have made several attacks on the

fort within the last few days--have burnt and destroyed all the houses

and other property in the neighborhood, and it is said the woods are

alive with them. All the hostile bands from upper Rogue River are

there, together with the six or seven bands who joined them from this

district. The citizens, however, are strongly posted on the sand beach

a mile or two from any timber, and will doubtless be able to hold out

till the steamer returns from the Columbia River, when, if

reinforcements have not arrived, they will be taken to Crescent City,

California, by the steamer.The boat which left here day before yesterday was capsized on attempting to land at Rogue River, and eight of the ten men in it met a watery grave. Government will be compelled to send some thousand men here ere these savages can be properly chastised. If she has not enough regulars, we must have more volunteers. Something must be done, and quickly. The expressman says that two more of the volunteers made their way into Rogue River, but were nearly dead from severe wounds. All of the 1,300 Indians in this district who have not yet joined the enemy have come within a few miles of this fort, and express great friendship. But we are satisfied from all the information we can glean that this is a part of their general plan, and that so soon as the enemy arrive they intend to join them. It would probably serve them right were we to pounce upon and kill every man of them. But this is not politic--not humane. Perhaps the best and only thing to be done, under the circumstances, is to let them alone, and should reinforcements arrive in time, they may be deterred from joining the enemy. I have no time to enter into the detail of the origin of the war. You will see from letters to you previous to any outbreak that the Indians have had much to complain of, but so far as those in this district are concerned, they have been kindly and justly treated, so long as the late Indian agent Ben Wright was in office. And yet the rascals pounced upon him as the first victim. Treachery is so predominant a trait in the Indian character that it alloys all others, and now, after more or less intercourse with different tribes for the last six years, I have come to the determination never to rely upon an Indian's good faith, unless circumstances or his passions enjoin him to keep it. My love to all. Your Brother

Fredonia

Censor, Fredonia, New York, April 30, 1856, page 2LATEST FROM THE SOUTH.

Umpqua Correspondence of the Statesman. Deer

Creek, March 12, 1856.

Friend Bush:--An express arrived here through the mountains last night

from Port Orford with the news that one hundred men or more were

surrounded in their entrenchment at the mouth of Rogue River by the

Indians, without any chance of retreat, that the Indians already there

number between three and four hundred. A whaleboat left Port Orford for

the purpose of communicating with the whites, but was swamped in trying

to land, and as fast as the crew came ashore they were killed by the

Indians, only two making their escape.

Capt. Tichenor tried to approach them with his schooner Nelly but could not on account of the winds. It was said when my informant left that these men had but about four days provision. This man says there are about eighty men at Port Orford including 30 U.S. troops. They have erected a fort by setting up planks about six inches apart and filling the space with earth. The people at Port Orford think they can stand a siege but expect the town will be burnt. A rumor tonight says that the Coquille and Coos Bay bands have left for the mountains with the intention of joining the hostile Indians. If this be true all the property along the coast as far as the mouth of the Umpqua will be destroyed, as it is said the people at Coos Bay have no arms, what few they had being sent down the coast. The messenger who brought this news here went south this morning to see Gen. Lamerick, hoping he would be able to send some men to the relief of the people on the coast. Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 18, 1856, page 2 Port Orford Correspondence of the

Statesman.

Port

Orford, Feb. 25, 1856.

Editor Statesman--The

Indian difficulties so long threatening, and so repeatedly sounded in

our ears along the valley of Rogue River, have now in reality touched

our vicinity. Our neighbors at the mouth of Rogue River, and those

residing on the coast between this and that place, have met with an

atrocious and melancholy fate. News by express, and also by one or two

persons who escaped barely with their lives, after intense fatigue and

hunger, was brought here that the Indians, comprising all or nearly all

the different bands at the mouth of the river, attacked the whites at

seven different points all within ten or twelve hours' time, and

extending along the coast some ten or twelve miles. The company of

volunteers organized under the proclamation of the governor, now

encamped at the mouth of Rogue River for the purpose of filling up

their company, and our Indian agent B. Wright, who it is greatly feared

has also shared a similar fate, who was also on the ground, and not the

slightest fears were entertained of any difficulty from the Indians,

and quite a number of the volunteers were absent from the camp at the

time of the attack, and it is not yet ascertained how many were absent

from camp or how many were killed. We forbear mentioning names of

persons who we suppose are killed, but we can without doubt record the

names of Lorenzo Warner of Livonia, Livingston County, N.Y., Nelson

Seamans of Cedarville, Herkimer Co., N.Y., John Geisel, his wife and

five children, all their buildings burned and every mark of

civilization destroyed.

The excitement is intense, and should we record every report we should extend our communication beyond a creditable length. At a subsequent time, and when the excitement passes off and a full statement of facts can be authentically ascertained, I will report in full. Yours truly, JAS. C. FRANKLIN. Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 18, 1856, page 2 IMPORTANT NEWS FROM PORT ORFORD.

---- Capt. Ben Wright, Indian Agent, Killed. ---- TWELVE MEN ATTACKED--10 KILLED! ---- THE INDIANS 300 STRONG! All Well Armed with Rifles and Revolvers. ---- The Settlements Burned and People Murdered. ---- PORT ORFORD WITHOUT DEFENSES, AND THE PEOPLE AT THE MERCY OF THE SAVAGES!! ----

(The following letter from Hon. R. W. Dunbar, Collector of the

Port at Port Orford, contains sad and startling news, and his

statements may be relied upon as correct.)

Dear Waterman--Our town was thrown into the greatest excitement this evening by the arrival of one of the volunteers of the company, who until recently were in a blockhouse at the Big Bend of Rogue River, but who, since the murder by the Indians at the mouth of Illinois Creek of two men employed in transporting supplies for the company, had removed to within four miles of the mouth of Rogue River, where grass, water and supplies could be had and until the company could receive expected reinforcements to fit them to make a demonstration upon the enemy. On the morning of the 22nd inst., while a part of the men were absent from camp, leaving only twelve men--at dawn of day they were attacked by an overwhelming force of the enemy, and as is supposed, all but two of them killed. Mr. Foster, one of the survivors, states that as soon as their condition became known, he advised the men to separate and take to the woods; they did so, and when closely pressed, "the bullets flying thick as hail," he threw himself into a thicket, crawling close to the ground--he occupied a favorable position to witness much that transpired--saw the Indians in five different detachments, led by a fellow called Aenas, a Klickitat. He supposed they numbered three hundred--the Indians were all well armed, with rifles and Colt's revolvers. While hunting the brush very near him, one of the men was discovered and fired upon by some twenty shots as he attempted to run; this drew their attention from himself, and he escaped notice, lying still until night enabled him to get away under cover. He kept in the brush and woods as far as "Euchre Creek," midway between Port Orford and Rogue River, on the beach trail. All the ranches at Euchre were burned; no one could be seen by him as it was night--he took to the hills again, arriving here this evening. A small schooner had been dispatched from the mouth of Rogue River and arrived the same evening, confirming the news. The other volunteer spoken of as one of the two had made his way to the mouth of the river and gives a similar statement that of Mr. Foster and supposed that he was the only one left of the whole camp. Dr. White of Rogue River was at "Euchre Creek Ranch" when the savages made a descent upon it on the 22nd inst. at 5 o'clock p.m. They killed Mr. Warner and Mr. Seamon; Mr. Smith, a sick man, made his escape to the woods, where he remained forty-eight hours without food. Dr. White also escaped in the thick brush towards Rogue River, and reports that Mr. Geisel, family and two men were killed at his ranch by the Indians, and it is supposed that every ranch near Rogue River is sacked, the people surprised and killed. The captain of the volunteer (John Poland) had gone the evening before the attack was made on the attack with the Indian agent, Capt. Ben. Wright, across the river. An Indian had come into camp and told that Aenas was in the camp of the Mikonotunnes, and that they wanted Wright to come and take him away, as they did not want him there. Wright, knowing him to be the great leader, was anxious for his capture, and was thus led into the snare evidently laid for him. Mr. Wright has been deceived as to the friendship of the Indians in his district towards the whites. In the fight on the 22nd inst. (for some of the volunteers did give battle, though overpowered by numbers), and in the sacking of the camp after all was over, many of the pretended friendly bands were distinguished gloating on the spoils! The settlers at the mouth of the river are in danger, and hourly expecting an attack. Our town is weak--we build a fort tomorrow, preparatory to meet the enemy, whose approach is step by step. The garrison here is illy prepared to render aid, being scarcely more than able to protect the public property--the command numbers about twenty-four men. We are certain that the Indian Agent Ben. Wright is killed, and satisfied now that all the coast bands will be drawn into the general war which is upon us; the unchecked successes of the hostile Indians has put them in possession of arms and munitions enough to arm all the unarmed Indians on this coast and make them equal man for man with the whites. Unless the regular army come to our relief, I fear that the settlers on this coast will be cleaned out in a short time. We shall make the best defense we can with the means at our command, although nearly all the arms and munitions in this quarter seems to be in the hands of the enemy; how it is, I know not, unless it be by conquest--there is, I fear, gross blame somewhere. The settlers north as far as Coquille are all in town for protection; it is a painful sight to contemplate, to see them compelled to abandon everything to the merciless savage--drag their women and children through rains, and all the inclemencies of a disagreeable winter at so great a sacrifice, and to know that there is no relief. Whatever may have been the origin or cause of this war, here are innocent parties, good and peaceable citizens, struggling against the vicissitudes of this country, exposed to the scalping knife, of savage warfare, or compelled to abandon the results of many hard months' toil. How long will the government withhold her protection to these defenseless people? We have not the men to meet the combined Indian forces of the south, now reinforced by the coast bands; and our position is such that at best we cannot expect to hold out for a great length of time. We have no further news from Rogue River up to [the] 26th. Great anxiety is felt, but we care not leave our post.

In haste, yours,

P.S. I would say that the coast Indians

above us

north, and those at Coquille, have as yet committed no act of

violence

R. W.

D.R. W. DUNBAR. Oregon Weekly Times, Portland, March 8, 1856, page 2 This letter was reprinted, without a signature, in the Table Rock Sentinel of March 22, page 3. FROM

CRESCENT CITY.

The Crescent

City Herald of

March 5th says that the inhabitants of that town were dreadfully

frightened by the news of the attack of the Indians on the settlement

at the mouth of the Rogue River. On Friday morning, before daylight,

news came of a threatened attack of the Indians on the town; the women

and children were gathered in the brick store in anticipation of a

descent, and remained there until daybreak. Shortly after some friendly

Indians arrived, and reported that the apprehensions of the inhabitants

arose from a party of Mexicans with mules approaching the city.Daily Union, Washington, D.C., April 18, 1856, page 2 (From

the Democratic Standard.)

HORRIBLE INDIAN MASSACRE. Seventeen Persons Killed by Indians Near the Mouth of Rogue River, Among Whom Were Ben. Wright and Capt. Poland.

From Judge Pratt, who came up on the Republic, we

have obtained the following details of the massacre of whites near the

mouth of Rogue River. Judge Pratt was furnished with these particulars

by Maj. Reynolds, the officer in command of the few troops stationed at

Port Orford, and who came on board the steamer while lying at that port.

The narrative will be better understood by first stating that Ben. Wright had been sent by Gen. Palmer down the coast with authority to collect the friendly Indians about the mouth of Rogue River and cause them to be removed up the coast to Coos, so as to be separated from the contamination of the hostile tribes dwelling higher up the river. At the mouth of Rogue River is a settlement of whites embracing about 30 persons. About 4 miles up the river and on the south side was a house, the residence of a white by the name of McGuire, who had been acting as an Indian agent. Opposite on the north side is an Indian village of the Tututnis. This tribe, together with the Shasta, coast, Mikonotunnes, and a few other small tribes living in the vicinity, were regarded as friendly Indians; while the Galice Creek, Applegate and Cow Creek tribes living father from the coast were known to be hostile, and to have made endeavors to induce these coast Indians to join them against the whites. One Eneas, a half breed, is the leader of the hostile bands in that section. The mouth of Rogue River is about 30 miles below Port Orford. On the 22nd Feb., Ben. Wright and Capt. Poland, with about 40 troops, had been collecting these Indians at [the] Tututni village preparatory to proceeding with them up the coast. On that night about 25 of the troops left their arms with their comrades and went down to the mouth of the river to attend a ball. Wright and Poland went over to McGuire's house to remain during the night. The remainder of the force, 15 in number, lodged in camp on the north side of the river near the Indian village. About 2 o'clock in the morning of the 23rd, the soldiers in camp were awakened by the noise of a scuffle over the river at McGuire's house. They heard no shots fired, and the darkness prevented their being able to see the nature of the trouble. They remained awake, proceeded to prepare their breakfast, and were ready to partake of it just at the first dawn of day. A Mr. Foster, who escaped and reached Port Orford on the 24th, says that as he was about drinking his coffee a volley of musketry was fired into camp, one ball knocking his cup from his hand. He immediately rose up, and by the light of the camp fire observed that the Indians were in their midst in great numbers. He immediately took to the brush, and succeeded in secreting himself under a log about 300 yards distant from camp. The Indians fired several shots after he left camp, and when daylight had fully appeared, they yelled and whooped and danced like demons. They came several times close upon him as he lay concealed. He recognized among them Eneas the half breed, whom he knew, and understanding their language, he heard them say that they had killed and had found the bodies of 13 of those in camp. The other one besides himself who had escaped he knew not nor where he could be found. He was enabled to move his position undiscovered, so as to see that McGuire's house had been burned, and this led him to suppose that the scuffle which was heard there in the night was the act of butchering the inmates by the Indians, and that they had done this without firing a gun to avoid alarming the soldiers in camp. Ben. Wright, Capt. Poland and three others were the occupants of the house that night. Foster remained in his hiding place till the [night] of the 23rd, when supposing that the Indians had proceeded directly to the settlement at the mouth of the river, he left his retreat and made all haste for Port Orford, where he arrived on the 24th. The other person who escaped the massacre also lay concealed until the night of the 23rd, and then proceeded immediately to the mouth of the river and gave the alarm. The citizens sent a small schooner, which was lying in port, immediately to Port Orford for assistance. This craft arrived there before Foster and apprised Maj. Reynolds of the massacre. The Major, having only about 30 men at his command, was unable to render the aid asked for. But Capt. Tichenor and a few of the settlers at Port Orford returned immediately with the schooner. The fate of the settlement was not known on the 27th when the Republic left Port Orford. The crippled condition of the Republic, in consequence of a fire on board, and the excited state of her passengers, rendered it impossible for her captain to aid Maj. Reynolds, and hence the Major sent up a requisition to Ft. Vancouver for a company of troops. The Indians engaged in this massacre are said by Foster to have been the Galice Creek, Applegate, Cow Creek hostile bands combined with the coast Indians who have been hitherto friendly. When the steamer left Port Orford, Maj. Reynolds was fortifying that post. The Oregon Argus, Oregon City, March 8, 1856, page 2 Memoranda.

The P.M. steamship Republic,

Isham,

comd'g., left San Francisco Feb. 23rd; at 5½ p.m., on the

night of the

24th, experienced a heavy gale from N.N.W., which lasted 36 hours; on

the 27th, off Port Orford, the ship was discovered to be on fire over

the boiler, but through the exertions of the officers, assisted by the

passengers and crew, it was soon extinguished, and the ship's course

altered for Port Orford, where we arrived in safety; upon examination

the ship was found to be but slightly damaged; at midnight left Port

Orford, shaping out course for Columbia River, the bar of which we

crossed on the morning of the 29th, and arrived at Astoria at

10½

a.m.,; landed mail, freight and passengers, but owing to the ebb tide,

we were detained about four hours; touched at St. Helens, and arrived

at Fort Vancouver at noon on March 1st; left again on the 4th inst., at

11 a.m., with Company G, 4th Infantry, composed of 80 men, under the

command of Capt. C. C. Augur and Lieut. Macfeely; arrived at Astoria at

1:20 p.m., on 5th inst., but owing to the state of the bar, we were

detained three days; left at 11 a.m. on the 8th, and crossed the bar at

2 p.m.; arrived at Port Orford at 6½ p.m. on the 9th inst.,

landed the

troops and left at 11½ p.m. for Crescent City, where we

arrived on the

morning of the 10th, at 10½; left at 2½ p.m. and

arrived at Trinidad at

8 p.m.; left at 11½ p.m. and arrived off the Heads at 4 p.m.

on the

12th.

"Two Weeks Later from Oregon," Daily Alta California, San Francisco, March 13, 1856, page 2 We were just handed the following letter by Mr. William Wright, from Mr. Dunbar, Collector of Customs, detailing the particulars of the murder of his son, Capt. Benj. Wright, by the Indians in Oregon. Port

Orford, March 5, 1856.

C. W. Wright, Esq.--Sir, It is my painful duty to inform you of the

death of Capt. Benj. Wright, sub-Indian agent of this vicinity. He had

been among the Indians under him for several days, arranging matters

with them, and giving them advice. Indian hostilities had been

committed in Oregon to an alarming extent. It was feared that as they

were not far from us--very near to some of the bands in his

district--that they would frighten or persuade some of the peaceable

Indians to join them. He had always confidence that he could control

all his Indians, thus he went among them; though the war party was

known to be in the vicinity, no danger was apprehended. On the 22nd day

of February he was solicited by some of his own Indians to come (or go)

amongst them on business; he did so in company with Captain John Poland

of the volunteers. They slept in a house on the south bank of Rogue

River. At about 3 o'clock on the morning of the 23rd inst., he was

surrounded, having been betrayed by his own Indians, and awakened only

to be butchered, he and his companions. It is reported by Indians that

Ben was called to the door and then grappled and killed by a blow from

a hatchet and then cut to pieces. I was necessary that they should make

no noise at the time as there was a small force of volunteers a short

distance off; after his death the company of volunteers were surprised

and cut to pieces. Those before supposed peaceable joined the war party

and made a descent upon the settlers, murdering all, laying waste to

their improvements, and as far as we can learn from this to the

California line, at the mouth of rogue River, everything was destroyed

but the picket fort, and the few there in the fort surrounded and

hemmed in and have no communication. The whole country is in a state of

war, and we are all forted up and hourly expect an attack. We are too

weak to go to fight the Indians as they are strong in force, and so

many of our people have been cut off, while their unchecked success has

drawn to these the support of all the bands on this coast. Our only

hope now is in the U.S. sending us aid; whether we will have our wishes

and only hopes realized, I know not. Mr. Wright's effects are in my

charge.Your

friend,

Richmond Palladium, Richmond,

Indiana, April 24, 1856, page

2R. W. DUNBAR Collector of Customs. An Indian Agent Killed.

We learn,

says the Philadelphia North

American

of Saturday, by a private letter from Port Orford, Oregon, that Capt.

Ben Wright, sub-Indian agent of that district, was murdered by the

Indians on the morning of the 23rd

of [February].

He was, we believe, a Philadelphian. He died in the performance of his

official duties. As the hostilities of the Indians had assumed an

alarming character in Southern Oregon, and some of the warlike Indians

are not far from the Port Orford settlements, it was feared that the

peaceable Indians might be persuaded or intimidated into joining the

savage army. Capt. Wright has always had great confidence in his power

to control the Indians, and under the influence of this he went amongst

the tribe of his charge, apprehending no danger, notwithstanding that a

war party was known to be in the vicinity to which he went. On the 23rd

of February, having been solicited by some of his own Indians to go

among them on business, he went in company with Capt. John Poland, of

the volunteers. They slept in a house on the south bank of the Rogue

River. At about three o'clock on the morning of the 23rd of [February],

the house was surrounded, and Capt. Wright and his companions were

murdered by the hostile savages to which his own professedly peaceful

Indians had betrayed them. Some of the Indians say that Capt. Wright

was called to the door, grappled and killed by a blow from a hatchet,

and then cut to pieces. There was a small force of volunteers a short

distance off, but the work was done so noiselessly that they heard

nothing of it, but were themselves immediately after surprised and cut

to pieces.After this bloody massacre, the treacherous friendly Indians joined the war party in open revolt. They at once made a descent upon the settlements, laying waste all before them between Port Orford and the California line, and murdering all the whites encountered on their way. At the mouth of Rogue River, everything was destroyed except the picket fort, in which the few survivors had assembled. There they were hemmed in by the savages, the communications all cut off, and at the date of the letter alluded to, March 5th, the whole country was in a state of war. The writer, R. W. Dunbar, Collector of the Customs at Port Orford, says: "We are all forted up and hourly expecting an attack. We are too weak to go out to fight the Indians, so many of our people having been cut off. The unchecked success of the Indians has drawn to their support all the bands on this coast. Our only hope is in the United States government sending us aid." Port Orford, from whence the letter was sent, is a town on the southern coast of Oregon Territory, located at the head of Tichenor Bay, which is a small sheet of water setting in from the ocean, above Rogue River. The Indians north of Port Orford bear the designation of Quatomahs. Those immediately south of it are called Euchres, while on Rogue River there is another tribe called Tututnis. All these tribes are now hostile. Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, Buffalo, New York, April 30, 1856, page 2

THE ROGUE RIVER WAR.--Through the politeness of Dr.

Holton,

who arrived on the Republic from the fort at the

mouth of Rogue River, via Port Orford, we learn that in attempting to

open a communication between Port Orford and that place, by sea, a

whaleboat was capsized, containing eight men from Port Orford, six of

whom were drowned; the other two succeeded in getting into the fort.

At the time the doctor left (6th inst.), they had succeeded in redeeming Mrs. Geisel, daughter and infant about six weeks old--her husband and three sons having been killed in the attack of the 22d February. On the 2d inst., five white men and one negro left the fort for the purpose of securing some potatoes that were not destroyed by the fire at the mouth of the river, [and] although well armed, [they] were cut off and every man killed, since which time no persons have ventured to leave the fort, forty men being kept on guard day and night. The whole number of persons in the fort being 26 men (five wounded), 7 women and 12 children. The Democrat, Defiance,

Ohio, May 3, 1856, page 2

Port

Orford, March 8, 1856.

Friend

Bush--By the steamship Republic,

which

touched here on her trip up some eight days since, we gave a short

account of the awful massacre that has taken place at or near the mouth

of Rogue River, and now we have only a few moments to add other and

nonetheless melancholy events.Shortly after the outbreak, a whaleboat set out from this place for the scene of horror, for the purpose of keeping a communication with the fort at the mouth of Rogue River, and on going ashore at or near the fort, the boat capsized and six men were drowned. We have not time to give a detailed account of the massacre, as the steamer is now in the harbor, but will give a list of those killed, viz.--Benjamin Wright, our much esteemed and efficient Indian agent, John Poland, captain of the volunteers, Pat. McCullough, Pat. McCluskey, John Idles, Henry Lawrence, Barney Castle, Guy C. Holcomb, Joseph Wilkinson, Joseph Wagoner, E. W. Howe, J. H. Braun, John Geisel and four children, his wife and daughter taken prisoners, but since exchanged. Martin Reed, Geo. Reed, a negro, name unknown, Lorenzo Warner, Samuel Hendrick. Those were killed in the first attack. Since that the following: Henry Bullen, L. W. Oliver, Dan Richardson, Adolph Schmoldt and Geo. Trickey, to which we add the names of those drowned, viz.--H. C. Gerow, merchant, and formerly of N.Y., John O'Brien, miner, Sylvester Long, farmer, William Thompson, boatman, Richard Gay, do., and Felix McCue. Efficient and energetic measures have been adopted by Maj. Reynolds, commander of the military fort, for a sure defense, and the citizens have also erected a fort and formed themselves into a company for the purpose of cooperating with the regulars. Yours, &c. JAS. C. FRANKLIN. Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 18, 1856, page 2 Drowned, in Rogue River, Oregon, on Thursday, Feb. 28, by the upsetting of a boat, Mr. Hiram C. Gerow, late of Williamsburg, L.I., aged 41 years. "Died," New York Herald, April 22, 1856, page 5 Lewellyn W. Oliver, son of Benjamin Oliver of Bath, was killed by the Indians at the mouth of Rogue River in Oregon, on the 25th of February. Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Bangor, Maine, May 23, 1856, page 2 . . . we have numerous interesting letters from our correspondents, among which we select those of Mr. Franklin and Mr. R. H. Smith, U.S. Postmaster at Port Orford, as containing the most news. The former may be found in another column, and from the latter we make some extracts below. Mr. Clarke Smith, brother of the writer, reported killed by the Indians in the Rogue River massacre, has fortunately escaped, having taken to the woods and made his way after incredible suffering to Port Orford. Port

Orford, O.T., March 8, 1856.

Since my last letter to your paper our vicinity has been the scene of

the most distressing occurrences, the particulars of which I forwarded

you by the last steamer. The Indians here are now under the

surveillance of Major Reynolds, at the barracks, where they are kept

inside the government reserve and fed. They are given to understand

that in the event of their being found outside the reserve they are to

be shot down. They are carefully but humanely kept, and no

communication allowed with any strange Indians from among the hostile

tribes of the interior.We live in our block fort at night. The quarters are also fenced in and the log houses turned into forts. The late melancholy occurrence, by which we lost six citizens by drowning, adds to the general depression of feeling. The Port Orford Indians have given up their arms. The "Sixes" tribe have also come in and given up all they said they had. But their statements are not credited. There are above us by the lagoon about one hundred men and two hundred squaws and children. Major Reynolds is feeding them. More troops are expected when the steamer arrives. We expect the town will be burned up every night. An invoice of two or three dozen rifles would find an immediate and profitable sale. [no signature]

"Highly

Interesting from Port Orford," Daily Alta California, San

Francisco, March 20, 1856, page

2LETTER FROM PORT ORFORD.

THE INDIAN DIFFICULTIES THERE--PARTICULARS OF THE ROGUE RIVER AFFAIR-- SIX PERSONS DROWNED--SUBSEQUENT MOVEMENTS OF THE INDIANS, ETC.

(The following

letter containing fuller particulars of the affair at Rogue River is

sent to us from Port Orford with the request of many of the citizens

that we should publish it. A portion of the news it contains has been

previously published.)

Port Orford, O.T.,

March 8, 1856.

Necessity calls upon me at this moment

to record one

of the most atrocious outbreaks of the Indians that has ever occurred

in this country and the cause of which yet remains a mystery.

Difficulties of a serious and disastrous character have for several

months past been enacted in other parts of Oregon, but none have reach

our vicinity until recently. On receiving the proclamation of the

Governor for volunteers, an effort was at once made to raise a company,

and after being partially completed it was detailed for service. A tour

was taken through the Indian country by the volunteers, who were

accompanied by a detachment of U.S. troops from this place. After being

absent a few days the troops returned to their quarters, and the

volunteers repaired to the mouth of Rogue River, or near that point,

for the purpose of filling up their company. This occurred about the

first of February, and from this date up to the 22nd ult. no hostile

feeling was perceptible among any of the band of Indians residing in

the vicinity of the volunteers' encampment, and the agent had the most

explicit confidence in their integrity and sincerity of motives. But

treachery, the ruling character of the Indian, could not be secreted

any longer, and on the evening of Feb. 22 gave vent to its ruling

passion. On that evening, the Mikonotunne chief sent word to Capt.

Benj.

Wright, Indian agent, to "come and take away Eneas,

for he was a bad Indian." This Eneas is a Canadian Indian and has been

in Oregon for several years, and talks several different languages.He had professed great friendship for the whites, but sometime during the month of January he deserted the cause of the whites and joined the belligerent band of Indians. Capt. Wright returned the message with a request that Eneas should come and see him, or meet him at a certain place, to which Capt. Wright, accompanied by John Poland, captain of the volunteers, repaired. These communications were exchanged on the afternoon of February 22nd, and at the same time the Indians, some twelve miles distant, attacked the ranch of Mr. J. C. Smith. The Indians came to the house about 5 o'clock p.m., in their usual friendly and peaceable manner, and requested Mr. Warner to go a short distance from the house and look at an otter skin, but he had not gone more than thirty yards from the house before he was shot dead, without any chance of defense. Mr. Smith's attention was about the same moment attracted by the approach of some fifteen or twenty Indians from a different direction from which Mr. Warner had gone. Mr. Smith at once discovered the belligerent appearance of the Indians, and immediately closed the door and prepared for their reception. Mr. Smith and Dr. White (the only occupants) defended the house for thirty or forty minutes, during which time the Indians kept up a continual shooting at the house, and then it was set on fire, and Messrs. Smith and White were compelled to avail themselves of the chances of escape, which they effected amidst continual bad shooting of the Indians. Mr. Smith directed his course for this place, at which he arrived on Monday following, after suffering intense fatigue and hunger, and Dr. White sought the fort at the mouth of Rogue River, at which he arrived on the following day. From thence the Indians commenced their inhuman and atrocious work and directed their course towards Rogue River, killing all the inhabitants except two females, who they retained in capture, and burning every building that fell in their course. Early in the evening of the same day, Capt. Benjamin Wright, our worthy and efficient Indian agent, and John Poland, of the volunteers, who had according to an agreement above spoken of assembled at a specific place on the south side of Rogue River for the purpose of an interview with Eneas, the Canadian Indian, but sad to tell, they were both massacred as it is supposed by the same Eneas and his band of demons. On the following morning, at daylight, the volunteers were attacked by the combined forces of all the Indians occupying the vicinity of the mouth of Rogue River, and in fact extending some thirty or forty miles up the river. The volunteers were taken wholly by surprise, from the fact that they were among their friends, as they supposed, and several of the company were absent on business for the company, soliciting enlistments &c. Of the volunteers who were present, only four made their escape. Mr. Charles Foster was pursued some distance and finally secreted himself in a small thicket, in which he remained during the day and watched the infernal rejoicings of the Indians over the inhuman and atrocious victory which they had achieved. He witnessed their dancing and division of the property which they had taken. The volunteers were divided in what is called two messes; one was camped in the open air, and the other in a house. Mr. Foster was in the mess which was camped in the open air, and the first camp attacked, and from where he was secreted he could witness the entire attack on the house. The men who were encamped in the house fired several shots, and from the fact that it is well known that those who occupied the house were good marksmen, several Indians were killed. Mr. Foster judged the Indians to number over three hundred who made the attack, and who continued firing at the house about one hour, and their firing ceased in the house, the goods were then removed, and the house set on fire. Mr. Foster remained secreted until after dark, and then set out for this place, at which he arrived on the following evening. Mr. J. K. Vincent, Mr. Elijah Meservey, and Mr. E. A. Wilson, slightly wounded, also escaped by secreting themselves for six consecutive days, and the Indians were during the whole time all around them, and not unfrequently coming within speaking distance, but finally they made their escape to the fort. Following is a list of those killed, including volunteers and citizens: Benjamin Wright, Indian agent; John Poland, capt. volunteers; Pat McCullough, Pat McCluskey, John Jolles, Henry Lawrence, Barney Castle, Guy C. Holcomb, Jos. Wilkinson, Jos. Wagoner, E. W. Howe, J. H. Braun, John Geisel and four children; his wife and daughter, thirteen years of age, taken captives; Martin Reid, George Read, Lorenzo Warren, Samuel Hedrick, Nelson Seamans, and a negro, name not known. There are a few more who are missing, and it is supposed that they are also killed, but hoping that they may yet make their appearance we forbear giving their names, but will as soon as their destiny is known. In addition to this we are compelled to record another misfortune, which is in ratio nonetheless melancholy. On receiving the sad intelligence from Rogue River, expresses were sent out in every direction to solicit all the whites to convene at this place immediately for the purpose of building a fort, and making other and all necessary arrangements for a sure defense, and all the friendly Indians had been gathered in and their arms secured. A whaleboat set out for Rogue River to learn the result of the outbreak, and keep up a communication between the two places. The party consisted of eight persons, via: H. C. Guerin, merchant, and formerly of New York; John O'Brien, miner; Sylvester Long, farmer; Richard Gray, boatman; Felix McCue, miner; William Thompson, boatman; Henry S. DeFremery, farmer, and Capt. Davis, miner, and on going ashore at the landing opposite the Rogue River fort the boat capsized, and all were drowned except Henry S. DeFremery and Capt. Davis. This said intelligence was brought up on Friday evening by Robert Forsyth and Mr. McGuire, who literally ran the gantlet and arrived safe at our place. By this express we learn that the Indians, numbering from three to five hundred, were encamped within one mile from the fort at Rogue River, but the whites are so situated that scouting parties are daily cutting off and adding to the list of Indians killed. All the Indians, or nearly all, between this and the Coquille River have been convened by order of the commanding officer at this place and their arms secured, yet we are here on the lookout day and night, anticipating an attack. Yours &c.

Daily Alta California, San

Francisco, March 20, 1856, page

2Clinton. LATEST FROM THE SOUTH.

Umpqua Correspondence of the Statesman. Deer

Creek, March 12, 1856.

Friend Bush:--An express arrived here through the mountains last night

from Port Orford with the news that one hundred men or more were surrounded

in their entrenchment

at the mouth of Rogue River by the Indians, without any chance of

retreat. That the Indians already there number between three and four

hundred. A whaleboat left Port Orford for the purpose of communicating

with the whites, but was swamped in trying to land, and as fast as the

crew came ashore they were killed by the Indians, only two making their

escape.

Capt. Tichenor tried to approach them with his schooner Nelly but could not on account of the winds. It was said when my informant left that these men had but about four days' provision. This man says there are about eighty men at Port Orford including 30 U.S. troops. They have erected a fort by setting up planks about six inches apart and filling the space with earth. The people at Port Orford think they can stand a siege, but expect the town will be burnt. A rumor tonight says that the Coquille and Coos Bay bands have left for the mountains with the intention of joining the hostile Indians. If this be true all the property along the coast as far as the mouth of the Umpqua will be destroyed, as it is said the people at Coos Bay have no arms, what few they had being sent down the coast. The messenger who brought this news here went south this morning to see Gen. Lamerick, hoping he would be able to send some men to the relief of the people on the coast. Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 18, 1856, page 2 Indian War at Port Orford--Letter

from Mr. Dunbar.

Port

Orford, March 4th, 1856.

Editor Times--Since

writing to you under date 24th Feb'y., other developments have taken

place. Up to the 28th Feb'y., no news had been received from Rogue

River; we were satisfied that all communication was cut off between us

and them. With a glass we could see that everything that they could

reach was being burned and destroyed by the savages, without our being

able to render assistance. Anxious to know the fate of the remnant of

our friends there, on the morning of the 28th ultimo

a company of eight resolute spirits, good men, took a boat and supplies

for twenty-four hours, and with the north wind sailed down. In trying

to land opposite the fort, the boat became unmanageable in the surf,

capsized, drowning six out of the eight men, with the loss of all their

arms and some ammunition for the fort. Capt. Davis of Coquille and Mr.

DeFremery swam ashore; H. C. Gerow, boatman, William Thompson, sailor,

Felix McCue, John O'Bryan, miner, and Mr. Long, farmer, were drowned.

The Indians tried, after the bodies came ashore, to rob and mutilate

them, in which three Indians were shot, and compelled to abandon the

spoils. The whole country is filled with the war party--having got the

assistance of all the coast bands between this and the California line.

The night after the sad accident, two men run the gantlet, came through the lines of the enemy, and reached this town in safety on the following morning, and report in addition to the above, that on the 24th the Indians in force appeared before the fort and made an attack, but were repulsed by the whites with the loss of several Indians, and no damage done to the fort. They, however, pillaged and burned all the buildings, on both sides of the river, and retain possession of the field. Mrs. Geisel, and little daughter eleven or twelve years old, spoken of in the former communication, were taken prisoners and hurried off into the mountains, instead of being killed. This news was brought to the fort by a volunteer escaping into the brush, by whom they passed on their road, after a day had elapsed. One or two wounded volunteers made their way to the fort and confirm the death of Capt. John Poland of the volunteers and Capt. Ben Wright, sub-Indian agent. Mr. Wright had to the last full confidence in his Indians, who evidently laid the plan for his murder. Capt. Poland and Capt. Wright were on their way to Port Orford with papers relative to the organization of the company, and Capt. Wright had been amongst his Indians, and believed them all right; but their plan was to put an end to him--they sent back after him and urged him to come back, when he was five or six miles on his way. From an Indian, the manner of his death is learned to have been by going to the house where Capt. Poland and himself slept, called him to the door on pretense, when a dozen at once grappled him by the arms, hair and body, and as it was necessary to kill him without noise, he was struck in the head with a hatchet, then cut in pieces with knives. Capt. Poland had a desperate struggle with the Indians--wounded some of them badly. He is said to have nearly cut off the hand of the 2nd chief of the Tututnis; this is, however, Indian intelligence, but is believed. Major Reynolds, in command of the fort, or garrison of the U.S. troops, has rendered every aid in his power to the citizens and for the protection of this place. Every part of the garrison is being fortified to protect the stores, etc. Soon as the death of the Indian agent was known here, Maj. R. at once took charge of the Indian Department of this district and set about bringing in all the bands not already implicated in the outrages below, desirous to keep them from taking part, and to gain time for help to arrive. He had the Coquille, Sixes Rivers, Elk River and Port Orford bands put on the military reservation, and is now furnishing them provisions. The great object is, if possible, to prevent communication between these and the war party at Rogue River; how long it can be done I know not--I fear not long enough to get reinforcements of troops. Pickets are kept at night. On two occasions they fired upon Indian spies in the night, from below. I close at half-past ten to attend a call to picket guard. Your friend, R. W. DUNBAR. Oregon Weekly Times, Portland, March 22, 1856, page 1 FORT

MINER, GOLD BEACH,

At a meeting of the citizens and volunteers held this day the

undersigned were appointed a committee this day to draft and present to

our fellow citizen, Mr. Charles Brown, a testimonial of the high

appreciation of this community for his brave and gallant conduct during

the negotiations for the release of Miss Mary Geisel from the Indians.

We therefore offer the following preamble and resolutions:March 7th, 1856. Whereas, the Indians did, on the night of the 22nd ultimo, enter the house of John Geisel, and did in the most shocking manner murder the said Geisel and three children; and, Whereas, the Indians did then take and carry away the widow of said Geisel and infant three weeks old, and a daughter of thirteen years; and, Whereas negotiations were yesterday opened with the Indians for the release of Mrs. Geisel and her children by means of an exchange of prisoners, which resulted in the release of Mrs. Geisel and her infant child, who were safely returned into this fort, and, Whereas, the Indians with their usual treachery did then refuse to give up Miss Mary Geisel as they had agreed to do; and, Whereas, the said Charles Brown did at this point voluntarily leave the fort and go unarmed at the imminent risk of his life, into a large band of hostile and armed Indians, which gallant act was repeated until he succeeded by skillful negotiations in effecting the release of the said maiden, whom he led in triumph into the fort, Therefore Resolved, by this community, that we hereby tender our warmest thanks to our fellow citizen, Mr. Charles Brown, for his brave, humane and gallant conduct on the above occasion. Resolved, That in thus voluntarily risking his life without solicitation, and without the hope of pecuniary reward for the noble purpose of releasing said maiden from captivity, Mr. Charles Brown has won for himself a high place among those whose names shall live when marble monuments shall have crumbled into dust. Resolved, That while the deeds of the conqueror are handed down to posterity, we claim a place in history for the name of Charles Brown, who, actuated by no mercenary motive, performed an act of true bravery and self-sacrificing intrepidity which stands side by side with the gallant acts of our country. Resolved, That as soon as possible this community will present to the said Charles Brown some more solid testimonial of our regard for his distinguished services above recorded. Resolved, That all the newspapers on the coast are requested to give this an insertion. Wm.

J. Berry,

Crescent

City Herald, May 21, 1856, page 2Alex. Sutherland, O. W. Weaver, Committee. Exciting Times in Oregon.

Our old friend Robert W. Dunbar, Esq., is having a hard time of it in

Oregon, with the Indians. He is Collector at the port of Port

Orford and thus writes to the Oregon

Times. After

giving a good deal of news of murders, &c., by the Indians, he

says:"Our town is weak--we build a Fort tomorrow, preparatory to meet the enemy, whose approach is step by step. "The garrison here is illy prepared to render aid, being scarcely more than able to protect the public property--the command numbers about twenty-five men. We are certain that the Indian Agent, Ben Wright, is killed, and satisfied now that all the coast bands will be drawn into the general war which is upon us; the unchecked successes of the hostile Indians has put them in possession of arms and munitions enough to arm all the unarmed Indians on this coast, and make them equal man for man with the whites. "Unless the regular army come to our relief, I fear that the settlers on this coast will be cleaned out in a short time. We shall make the best defense we can with the means at our command, although nearly all the arms and munitions in this quarter seems to be in the hands of the enemy; how it is, I know not, unless it be by conquest--there is, I fear, gross blame somewhere. The settlers North as far as Coquille are all in town for protection; it is a painful sight to contemplate, to see them compelled to abandon everything to the merciless savage--drag their women and children through rains, and all the inclemencies of a disagreeable winter at so great a sacrifice, and to know there is no relief. Whatever may have been the origin or cause of this war, here are innocent parties, good and peaceable citizens, struggling against the vicissitudes of this country, exposed to the scalping knife of savage warfare, or compelled to abandon the results of many hard months' toil. "How long will the government withhold her protection to these defenseless people? We have not the men to meet the combined Indian forces of the South, now reinforced by the coast bands, and our position is such that at best we cannot expect to hold out for a great length of time. "We have no further news from Rogue River up to 26th. Great anxiety is felt, but we dare not leave our post. "In

haste,

yours.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville,

Indiana, May 30, 1856, page 2"R. W. DUNBAR." The following letter was written by Mrs. William Tichenor to her son Jacob, who was in school in the Willamette Valley. The letter was sent to us by Mary Boice Capps. Port

Orford March 17, 1856

My Dear Son:I should have written to you immediately after your father returned from Salem, but owing to the great Indian excitement here and your father leaving home again in less than a week was why I did not write. . . . Now, my boy, I must tell you something about the Indian troubles here. About three weeks ago the Rogue River Indians commenced their hostilities. They have joined the hostile tribes and have destroyed everything at Rogue River, killed a good many of your acquaintance. About one hundred men, nine women and several children saved themselves by getting into a fort which they had prepared which is the only thing standing; it is in Prattsville on the bluff. We have had no news from there for more than a week, when two men ventured out at the risk of their lives by night and arrived here in safety. They say if they keep their position at the fort they are safe. The Indians have made several attempts but did not succeed, but several were killed each time. Troops were sent for immediately, who arrived here by steamer. There were over a hundred started from here yesterday for that place. Ben Wright was killed at [the] Tututnis' village where he had collected the Indians from the mouth of the river and all about to prevent communication with the hostile Indians as he thought. Most of the volunteers were killed who had been staying at Big Bend all winter but were with Ben Wright at the time. I cannot tell the number. Mr. Warner was killed at his house and house burnt and Mr. Seaman was killed; he was there at the time hunting. Mr. Geisel and two sons were killed. His wife and daughters were taken prisoners, but they have succeeded in getting them. They are now at the fort. Mr. Lundry came with the schooner immediately to save himself and it and brought the news. Your father returned with him the same night with a message from the Major to Rogue River if he could not go in the river to go to Crescent City. He could not go in the river on account of the many Indians at the mouth, so he went to Crescent City and sent his schooner to San Francisco with a message. There was a hundred and fifty troops landed at Crescent City by the last steamer. Your father is their guide through the mountains. Don't be uneasy about us, for we have a good fort here up on the hill where the old fort was, and we all go there every night. The Port Orford Indians appear friendly. They have collected them all together the other side of the garrison from Coquille down and taken their arms. Your little sister often speaks of you and would like to see you and then she takes a peep at your daguerreotype. Your father intended writing to you but was called away in such a hurry. I must stop and get ready to go to the fort, for it is almost night. . . . Get your uncle to please read this to you if he can make it out. Do not be uneasy about us. We will try and come soon, for I cannot stay in Oregon. Your

affectionate [mother] Nellie E. Tichenor

P.S.

About two weeks ago eight men started to go to Rogue River in a

whaleboat to learn the conclusion of things there. As there is no

safety in traveling by land and in attempting to go ashore the boat

capsized in the surf and six of them were drowned. One of the drowned

was Mr. Gerow, Sylvester Long, old Dick the boatman and little Billy.

The others I did not learn their names.Curry County Echoes, Curry Historical Society, January 1989, page 7 Port Orford Correspondence of the

Statesman.

Port

Orford, March 23, 1856.

Editor Statesman--The

steamer is now due from San Francisco, and we avail ourselves of this

opportunity of communicating such intelligence as we have received from

the seat of war, and such other matter which may be of interest to the

readers of the Statesman.