|

|

Reminiscences of Orson Avery Stearns, 1843-1926 Articles by the Rogue Valley pioneer. Click here and here for more on Sam Colver. Reminiscences of Pioneer Days and

Early Settlers

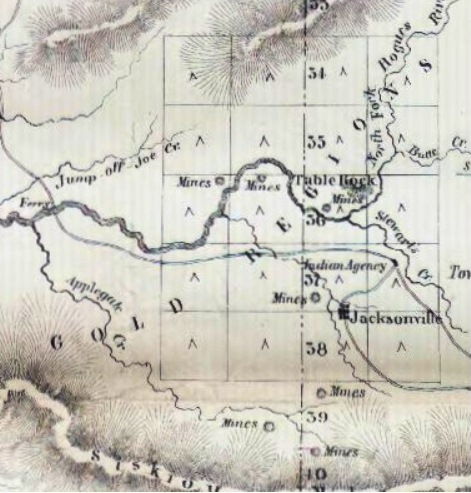

of Phoenix and Vicinity and A Brief Sketch of the Life and Character of Samuel Colver by Orson Avery Stearns 1843-1926 Including Six Letters of Transmittal to Mrs. Effie Taylor, Medford, Oregon From O. A. StearnsIn undertaking the task of recalling the early days of pioneer life, it must be remembered that nearly seventy years have elapsed since the first settlement of Rogue River Valley, and while the writer hereof was some two years behind the first settlers, [and] was little more than ten years old when in October 1853 his parents took up a donation land claim on Wagner Creek [and] his firsthand knowledge of incidents and events connected with the early events connected with the early events commenced, that many other people whose recollections have been printed and may in some ways differ from those here recorded, it does not necessarily follow that either their statements are at fault or that mine are the only true ones. People differ in their point of view, and while some have keener perception than others, their memories may not have equal capacity for retaining early impressions, for time does not equally deal with the faculties of all, as some have greater powers of retention of incidents than others, either by reason of greater vitality or from association of other incidents that tend to greater fixity of expression. It should not be forgotten that the writer does not claim infallibility in his reminiscence, but simply records here his remembrances as he can recall them and in a feeble way convey them to paper in his own way. He would further ask the reader to overlook the frequent repetition of the personal pronoun, as it seems indispensable that much of this narrative should be a recital of his own and relatives' experiences. With this lengthy introduction and apology, and the further explanation that it seems best to divide this article in chapters conformably with the various periods and subjects narrated, I will close.  A. A. Skinner's Indian agency marked on an 1854 map It should be remembered that the provisional government of the territory enacted a law in ____ as an inducement to settlement of the Oregon Country, which then embraced both Oregon and Washington territories and part of Idaho and Montana, giving to every settler one section of land, if said settler was married, and one-half section to a bachelor. By the terms of this law, the amount of land was cut in half after the year 1852, therefore emigrants settling in the valley after that time were restricted to amount of land, hence the variance between the earlier and later donation land claims. I believe the families of the two Colver brothers remained in the Willamette Valley until 1853, as up to that year there was a very sparse settlement, and the facilities for procuring provisions was so limited and prices so prohibitive that it would have been almost impossible to maintain a family. Believe there had been a few small fields of grain and vegetable gardens raised in 1852, but am not sure of that. When my father's family came in, in October 1852, it was difficult to obtain seed wheat at $10 per bushel, and everything else was correspondingly high. My father traded Jacob Wagner a two-horse wagon worth $200 for 100 hills of potatoes, and dug them himself. Flour was selling at $33 per hundred, and the sacks would stand alone after the flour was emptied out, the flour having been packed across the Coast Mountains from Scottsburg during the rainy season, uncovered, until wet in from ½ to 2 inches in depth, which hardened into a stiff dough and molded. All kinds of groceries were scarce and very high. The sugar we could get came in fifty-pound mats; it was more like sand as it was an ashy grey color and full of all kinds of filth. It was made in China, with the usual contempt for cleanliness that was characteristic of the coolie. My mother understood how to refine the sugar, after which it resembled nice clean yellow maple sugar, but was reduced in weight fully one-fourth in the process. For coffee, parched corn, peas and sometimes carrots or parsnips were used. Some people used browned bread crumbs, making what was termed crust coffee. The merchants those days carried but little clothing except miners' supplies, and people had to resort to picking up castaway clothing from the streets of Jacksonville, where it was the custom of the miners and gamblers to throw their old or soiled clothing after purchasing new, and a large part of these castaway garments were simply soiled, and after washing nearly good as new. As no children's clothing or footwear were obtainable, nor material for the making of them, the mothers of families were forced to make the clothing for their own and children's wear.

My father made lasts for the footwear of all the family except for

himself, and my mother made the shoes for the family, the uppers from

castaway boots picked up in the streets of Jacksonville in front of the

stores, the soles made from harness or saddle leathers picked up here

and there. All flour sacks were carefully washed and used to make

underwear, pillow cases, sheets, &c.

On account of the high price and poor quality of the flour, potatoes and squashes were added to make it go farther, and often the adulterant was a perceptible improvement to the quality of the bread. A few wild plums were to be had along the streams, and elderberries quite plentiful. They were largely used both as sauces, pies and dried for winter use, while some made a very fine wine out of them for use in case of sickness. After the harvest of 1854, the amount of flour from outside was largely supplemented by boiled wheat, and coarse meal made by grinding wheat or corn in large coffee mills bought for that purpose. As wild game was quite plentiful, and after the first winter beef was plentiful and of excellent quality, the fare of the settlers was much improved. There is a diversity of opinion as to the building of the first sawmill. I have always been of the impression that the sawmill on Wagner Creek, built by Granville Naylor and Lockwood Little and a Dr.____, was the first, and that of Milton Little [Milton Lindley?] of Gassburg second, but some claim that the sawmill built by the Emery brothers at Ashland was first. However, all three of these mills were erected very early and were running in 1854. Neither of them could saw much more in a day than two good whipsawyers. They used to claim they could either of them saw from 500 to 1000 feet in twenty-four hours, and they were always behind [in] their orders. The early settlers had to split or hew out puncheons for their doors, floors and other parts requiring lumber in their houses' construction. Most of the early houses were built of round logs with the bark on; some were hewn on the inside, a few hewn on both sides. All were chinked by putting in split pieces from shingle or shake bolts, and plastered over with mud. Chimneys and fireplaces [were] built of rough stone with split slats and mud for chimneys. Windows were very rare except for a hole cut through the logs and covered by cloth, usually an empty flour sack. Many of the first cabins had earthen floors, some rough slabs from the mills, with the sawed side up and the edges trimmed to fit by an ax. Mrs. Effie Taylor Chapter 2

The first school house was built by the settlers living near what is

now Talent.

It was of rough logs, with cloth-covered windows on two sides. Its

floor was of slabs, benches of slabs, with legs of round sticks

inserted in auger holes, no backs. The desks were simply rough plank

tables. It was erected on the bank of Bear Creek about one-fourth of a

mile from the farm of Jacob Wagner (now Talent). There being no school

districts yet established, it was started as a subscription school and

the name of Eden given to the school. The first teacher was Miss Mary

Hoffman, and her school consisted of the children of the surrounding

country for several miles in every direction, many of the pupils being

older than the teacher. The schoolbooks consisted of books brought

across the plains from near a dozen different states, and were as

varied as were the pupils. Scarcely any two families had the same

series of schoolbooks, and the organizing of classes was a very

difficult matter. Reading, writing and arithmetic were about all the

branches taught.

Believe I can give a pretty correct roll of the scholars, who ranged in age from seven to twenty-three years of age. They were Welborn Beeson; Joseph, Samuel, John and Robert Robison; Oscar, Orson and Newell Stearns; Theresa Stearns; Thomas, Martha and James Reams; Martha, Abi, Donna, Hiram and Solon Colver; Elizabeth and Nancy Anderson; Calvin Wagner; Mary, Nancy and Joseph Scott; Mary, Robert, Daniel, John and William Grey; Lewellyn Colver, and I am not sure but there were two or three others. Lew Colver was then about seven years old and rode to school on a little white pony. The teacher was a very good disciplinarian and, though very pleasant and sociable outside school hours, was quite strict in enforcement of discipline, almost entirely by moral suasion. At intermissions she joked and laughed with the other girls as though one of them. I remember one instance where she had received a love letter written entirely [Chinook] jargon, which she and the other girls were immensely tickled over, but which she was very careful not to let the other girls see the signature to. There were during the next few years four other terms of three months each taught in the log school house, though the attendance was never as large, nearly all the older pupils dropping out. The Rev. John Grey was the next teacher, and a more thoroughly disliked pedagogue it never was my misfortune to attend. He always rode to school on an old bay mare, with his children, five in number, trailing along behind or driven in front of him. On reaching the school house he would dismount, unsaddle and, giving his steed into the charge of one of his boys with instructions to take her down near the creek and stake her out where was good grass, would take his saddle and sheepskin blanket and spread on his stool, and there he would remain nearly the entire day, making all pupils and classes come up to his throne to recite their lessons; and woe to the laggard in recitation or who failed in any way to please him, for he generally kept a heavy ruler by his side, which he frequently used. He was particularly severe with his son John, who was a twin of William. John was in looks the image of his father, being dark and with very black hair and eyes, with a furtive look like a hunted animal. He could never recite his lessons through fear of his father, who would scowl at him fiercely when he came up to recite and upon the slightest mistake would hit him on the side of his head with the book he happened to have in hand, knocking him to one side, then hitting him on the other side and frequently continuing the performance until tired out. No wonder John Grey grew up to be a profligate and ne'er-do-well. He died in the Klamath poor farm several years ago. Henry Church was the third teacher in Eden school house. He was a tuberculous person and of a variable disposition. Quite capable, but his unfortunate disposition prevented him from having that esteem and confidence of his pupils that is necessary for success in teaching. A Mr. Reddick was the fourth teacher. He was a bachelor who had located a homestead just southeast of the Rockafellow place on Bear Creek. He did not amount to much as a teacher. A Mr. McCauley was the fifth and last teacher who held the position of tutor to the Edenites. He was a fairly good man and tolerably fair teacher who simply took up the vocation to fill a jobless space in life, and with no special desire to excel in the profession. The school house in Gassburg was built sometime in the late 'fifties. It stood about the same place now occupied by the Phoenix church. It was [a] lumber building, box and batten construction, I think, with fairly good homemade furniture. It was about 18x32 feet in dimensions and faced the east. It was lighted by three or four windows on north and south sides. The first school taught there, to the best of my recollection, was by Orange Jacobs, and he taught several successive terms. Many of the pupils who attended the Eden school attended the Gassburg school, besides many others living farther down the valley. Charles Hoxie; Al, Rose, Nettie Gore; Sarah Jane Arundell and a younger sister whose name I cannot recall [possibly Mary Jane]; William Burns; Wm. and Lucinda Williams; Doc & William Griffin; John, James, Nancy & (another younger sister) Justus; George & Alec Gridley; Lucinda and Ben Davenport; Lucinda Low; Wm. Belle; and a younger sister of the Hamlins. Several others whose names I cannot now recall were among Jacobs' pupils at one or more terms. I believe James Neil also attended one or more terms of his school. Lucinda Davenport married Jacobs at the end of his first term. One incident that might have had a tragical ending occurred during the second term. The Griffin and Justus pupils lived on the west several miles and frequently came and went away from school together. One morning upon reaching the school house a little before school time we were astonished to see the elder Justus pacing before the school house with a cocked revolver in his hand while Doc Griffin and a number of the other pupils from the same neighborhood stood by listening to the old man's tirade against Griffin, in which he repeatedly threatened to blow Griffin's head off for kissing or attempting to kiss Nancy Justus while on the way home from school the previous day. O. Jacobs soon arrived and prevailed upon the old man to defer his warlike intentions to some other time and place. Never heard of any sequel to the affair, though many of the boys agreed that any fellow who would kiss Nancy Justus deserved to be shot, for she was as homely and ungainly a creature as I ever saw, and as ugly in disposition as in looks. She afterwards married the two Ball brothers; not at the same time, but in rather rapid succession, both of them dying very suddenly and mysteriously after a short matrimonial experience. After Jacobs quit teaching and went to practicing law, a Professor John Rogers opened up school in the Colver Hall. He was a graduate and professor in Yale College, who left the East at the discovery of gold and had been drifting over the Coast for a number of years, and I presume had about reached the bottom of his purse. His school was an immediate success, his method of teaching new and unique. He seemed to have a mastery of every science and had [a] method of his own to classify and teach them. He encouraged studying out loud in school and elsewhere, claiming that pupils who were as absorbed in their studies as they should be would not be disturbed by the recitals of others. He encouraged mass rehearsals and had all the little scholars talking and quoting Latin phrases. Whenever there were visitors--and there were many--he would ask some of his younger scholars the Latin names of various animals and other objects and would smile and rub his hands gleefully upon their giving the correct answers in chorus. Your mother, my sister and one or two other girls were his prize repeaters, and he had them drilled to perfection as performers. He encouraged his pupils to take up many advanced studies for which they had no preparatory knowledge, and he frequently changed from one study to another so that his pupils had a smattering knowledge of many subjects rather than a thorough knowledge of a few. He was very punctilious and polite, and drilled his pupils in politeness. He even encouraged school parties on occasions when there was no school and gave them lessons in deportment, but always insisted on ending all parties as early as 12 M[idnight? meridian?]. He was quite religious, opening school with prayer when he insisted on bowed heads and closed eyes, his own being always open and watching vigilantly for any infraction of the rules by his pupils. His devotional exercises were taken standing, and once in a while his voice would cease while his firm and rapid strides carried him to some part of the room when one would hear some noise as of a person being lifted up and violently reseated. When the steps returned . . . the invocation was resumed in the place left off without a perceptible change of voice and concluded in [the] usual manner. At times he would be very nervous and hard to please, as though under a strain; at other times full of smiles and good nature. He taught one full year's term and part of another when his pupils had gradually dwindled and until he had so few that he dismissed school entirely. Soon after his school ended the cause of his nervousness and instability was discovered in the garret just above the platform where his desk stood, to which a small trapdoor gave him easy access. There were found several empty whisky bottles. It was also learned that in his accustomed early morning rambles he was wont to visit the store of McManus, who always kept a barrel of whisky on tap and who gave the professor his morning invigorator under the pledge of silence. After the discovery of the bottles and the departure of the professor, McManus told a joke he had on the professor. He had emptied one barrel of his liquor and, removing it, had placed in its place a barrel of very strong vinegar. He was out in his woodshed to get a load of wood to fill up his stove one day, leaving the professor standing by his fire when, coming suddenly into the back door, he saw the professor in the act of emptying a full glass of the supposed whisky down his throat. The choking and gagging that followed was terrible to see and hear but could not restrain Mc from a fit of laughter almost as paralyzing as the dose of vinegar to the professor. The latter it seems had been in the habit of helping himself to the liquor so temptingly displayed, and had heard Mc coming and hastily drew and swallowed the liquid for fear of being caught in the act, not knowing of the change in barrels. Mc said the prof. looked like a dog caught sucking eggs. As my attendance at the first term of Rogers' school was my last term of schooling, the names of succeeding teachers in Gassburg are only partially known. I think a Mr. Burhans taught the next term there, and a Sylvester Price I think taught there one term. I will add that while attending the Jacobs school myself my brothers and several other boys kept bachelor's hall ["batched it"] in a cabin about one hundred and fifty yards east of the school house. And for most of the time while attending the Rogers school my mother kept house for us in a hewed-log house just west of the blockhouse, in which the Davenports formerly lived. Dr. Timothy Davenport, with his wife, spent several winters in there prior to 1864, and finally Aunt Sally and Ben went back to Silverton to live. There were many old settlers living in the village when I entered the volunteer service in the fall of 1864. Many of them had died or moved away during the intervening years before I was again familiar with the happenings there. In the next chapter I will take up the early history of the village and relate the incident that gave the name of Gassburg to the place, as I was a personal observer of that incident. Chapter 3

At the time of

the beginning of the growth of the hamlet (as it might be termed) of

Gassburg, say about the period of 1855 to 1860, the settlement of the

region from Ashland down to what is now Central Point was almost

exclusively confined to donation claimants, mainly bachelors, usually

in pairs, with occasionally a family. Most of these donation claims

were taken in 1853. A few, including the claims of Samuel and Hiram

Colver, were taken up in 1851 to '52. The Myers brothers located

adjoining claims on [the] east side of Bear Creek in '53; adjoining

them on the north were the Rhinehart brothers, bachelors David and

Ezra, who were joined several years later by another brother. On the

Myers' south was a family by the name of Fisk, who later sold out and

went to northern California. Below Fisks', on Bear Creek, was the two

half-sections of Woolen & White, also bachelors. On the north

of

Woolen's was the two partnership claims of Peter Smith & ____

Thrash (afterwards bought by the Patterson family), then between these

claims and Bear Creek was the Wills claim, occupied for many years by

William (Bill) Smith, who jumped the claim of Wills when the latter was

shot by the Indians in 1853, and whose brother contested for and

finally obtained title thereto. Then there was the claim of D. P.

Britton, who was a young bachelor, for two or three years, but who

finally went to the Willamette Valley and ran away with another man's

wife down there, and lived thereafter on his farm and raised, together

with a family already started, quite a family whose descendants, many

of them (all girls), still reside in the valley. Next was the claim of

Henry Amerman, of one-half section, taken prior to 1853, extending

from Bear Creek eastward nearly to the mountain, where a canyon of

considerable extent ran up into the range, which was early occupied by

a Norwegian family by name of Canuteson. North of Amerman the two

Oatman brothers took a half section each, as they were both men with

families. Harrison B. and Harvey were their names, but they did not

remain on their farms many years, as farming was too strenuous work for

them, and they early moved to Gassburg, where Harrison started the

second store there and Harvey built a hotel which he ran in connection

with a saloon and billiard hall. A stable across the road was for many

years the stage barn for the Oregon and Cal. Stage Company, and Oatman

was host for the traveling public.

Continuing the enumeration of early settlers, down the valley N.W. from the Oatman claims which adjoined the Saml. Colver place on the north was a family by name of Quigley, whose place adjoined the high cliff of rocks to the east, and gave to the cliffs the name of Quigley Rocks for many years. Then came Wm. Mathes, the Rev. John Grey, the Scott family and a son-in-law whose name I do not now recall. The Pinkham brothers, Ed & Joe; the latter married Grey's eldest daughter, Mary (I think her name was). All these later named people were located in a sort of group north of the crossing of Bear Creek, the Grey and Scott children forming quite a percentage of the earlier schools. Randle was the name of widow Scott's son-in-law. They lived over there many years, and Randal I believe died there. He was a victim of phys (phthisic, I think they used to spell it). It is now called asthma. Having enumerated all the early settlers on the north of Bear Creek from the Myers place down as far as Wm. Mathes' place, I will now return up to the Woolen south line and give the names of as many on the south and west side of the creek as I can recall. The first was an old bachelor by name Dingman, who sold to O. Coolidge in 1861. Next (on the creek) [were] two bachelors, one whose name I have forgotten, the other was one of the schoolteachers later in the old log school house; his name was Reddick. Then the claims of Wm., Albert and George Rockafellow, whose claims were in the south of [the] junction of Wagner and Bear creeks. Jacob Wagner came next, who was supposed to be a partner of J. M. McCall, as they held down a half section land, though bachelors, for a number of years, McCall later giving way to James Thornton, who built upon and proved up on the south quarter-section. Up Wagner Creek in order named was John Beeson, John Robison, David Stearns, Lockwood Little and Granville Naylor, who built the first sawmill thereabouts if not in the entire valley. All these last-named were located on Wagner Creek. To the west and extending to and embracing Anderson Creek were, first, James Downing on a creek flowing into Wagner Creek and named after the locator of the claim. Then the Anderson brothers E. K. (Joe) and Firman, whose half-section extended from the John Beeson farm westward to the foothills. I will here state these lands were unsurveyed until 1865, and there was some confusion resulted in arranging the claims as originally taken to conform to the subsequent surveys. Owing to this confusion many claimants managed to smuggle in quite a lot of unclaimed lands and hold them until children of theirs came of age, when they took up the lands so smuggled and acquiring title thereto retained the same in the family. Adjoining the Anderson claim on the north and west was the claim of Woodford Reams, whose claim also touched the west line of Hiram Colver on the west. Then the claims of the Coleman brothers, Dad Little &c. Returning to Bear Creek and south of Hiram Colver's claim was the claim of two more bachelors, Nelson Smith and another bachelor who did not remain there and whose name I have forgotten. This is the place where the county poor farm is now located. It was purchased from the donation claimants by James Amerman sometime about 1858 or 1859 and occupied by him until his death in the '70s I think, when his widow married Col. Stone, who had charge of the same until it was sold to the county, I believe. Hiram Colver's house was just a little ways below on another note, later owned by a Mr. Harvey. There was just two houses between Wagner's and Gassburg up to 1855. The grist mill was commissioned in 1854 by S. M. Wait before the outbreak of the Indian war of 1855, and I think the sawmill of Milton Lindley was built about the same time. All that portion of Samuel Colver's farm west of the main road was then open pine timber with a scattering of oak and laurel trees. It was nice large saw timber and close by the mill. A few years sufficed to cut down all the saw timber, and the once wide-open forest soon became a forest of young pine and other trees, with a mass of rotting treetops and limbs, the refuse of the wasteful method of logging where only the straight limbless bodies of the trees were used. I remember well that from 1858 to 1861, the young growth was only tall enough to partially conceal the mass of waste tree trunks and limbs left by the loggers, and [at] the very last term of school that I attended in the old school house that stood at or near the present church, there used to be a contest among the boys to see who could run and jump over the highest young pines. About the time of the outbreak of the Indian war or just before, Sam. Colver and John Davenport commenced to build the blockhouse. They intended it to serve as a hotel and a store for general merchandise when completed, as also to serve as a rendezvous for settlers during Indian troubles. It was sometime during the early autumn of 1855 that the Indians, having met quite serious defeat on Rogue River, had scattered out and were attacking outlying scattered settlements that notices were sent out for all scattered settlers to concentrate at best available points for protection, as nearly all able-bodied young men were in the various militia organizations pursuing the campaign against the Indians, leaving only men with families to hold the entire settlement against possible surprise and attack. Most all families within a radius of six miles gathered at the site of the blockhouse then under construction, making quite a village of tents and wagons. Many of the men engaged in the work on the blockhouse as Lindley's mill was busy sawing out the 4x4 timbers. We remained there several weeks,with many coming and going. As Mr. Wait had quite a force of men working on his mill, the sawmill was being run night and day to furnish material for both mill and blockhouse, and several new industries sprang up, so there was quite a population. In the evenings, after the day's work was over, there was usually a huge campfire burning in a central location, and all the young people and many of the old used to gather around the fire, sing songs, dance and tell stories until bedtime. Among all this concourse, while there were quite a number of young men and bachelors, there was only one young marriageable woman. Her name was Kate Clayton, who was employed by Mrs. Wait to help her cook for the men employed on the mill. She was a girl about twenty and one of the most fluent talkers I ever met. As every young girl fourteen years of age was then considered a young lady and usually had a dozen or more admirers, Miss Kate, from her position as almost sole attraction of that assembly, always had every available male congregated in her immediate neighborhood. From her ability to carry on an animated conversation to a half-dozen or more admirers at once, as well as her prompt and witty repartee, she had been given the sobriquet "Gassy Kate," the term "gass" or "gassy" being recent slang for talk or talkative, or, as the dictionary would define it, "light, frivolous conversation." One evening soon after our arrival in camp, the usual campfire company was gathered around the fire, Kate as usual in the position of presiding goddess, while gathered around her in rapt admiration were her usual numerous admirers, among them Hobart Taylor, Dave Geiger, Jimmie Hays, ____ Black (given name forgotten), who had a very decided lisp. One of the men, during a lull in the talk, casting his eyes around the multitude of gathering tents, remarked, "I say! This is getting to be quite a town; we ought to give it a name." "I think tho too," said Black, "and I move we call it Gathville after Gathy Kate!" "Oh no!" said Hobart Taylor, "that sounds too small and insignificant. I move we call it Gassburg. That sounds more important." "Second the motion for Gassburg" came from a dozen or more at once. And Gassburg it became from thence forward, for over twenty years. Soon after the Indian war was over, in 1855 or '56, when a mail route was established between Portland and Sacramento a post office was established in a small office across the road from the grist mill, with S. M. Wait postmaster, and he took his fire insurance plate "Phoenix" as the name for the post office, but that did not serve as the name of the town for over a generation or more, and I have a very distinct recollection of all the above from actual personal knowledge. The village received no permanent increase as the result of the Indian scare, but soon after the war was over the discovery of gold in the '49 and Davenport diggings gave it a start. Chapter 4

The number of

the inhabitants of the village at the close of the Indian war in 1856

was approximately 75 or 80. There was the flouring mill owned by S. M.

Wait, the sawmill of Milton Lindley at the extreme north end of the

village, a carpenter and wagon shop by John Seiter, later owned by ____

Aspenwall, a tannery owned by Geiger bros. David and Wm.--am not

certain as to given name of last--a saddle and harness shop by Jimmy

Hays and Joe

Dies, a drug store by Dr. Colwell, a blacksmith shop by

Milton Smith, and there may have been one or two more small industries.

Grandpa Colver had come there with Grandma in the meantime, and Grandpa

had built a brick store which was rented to a Jew by the name of Samuel

Redlich, afterwards associated with another Jew, constituting the firm

of Goldsmith and Redlich. About the time of the gold discovery H. B.

Oatman built another brick store, a part of which was occupied as a

saloon and billiard hall.

Several different parties kept store in it, and I think several restaurants sprang up, some of them of very short life. During the years prior to the gold strike the popular amusements consisted principally of dancing parties, held generally in the Oatman hotel, but occasionally in the Colver hall, where also were held traveling shows and public gatherings of various kinds. There was organized a temperance society called The Sons & Daughters of Temperance, which had quite a membership from '54 until about '59. Quite a large number of the young men and women belonged, especially young men of the steadier and better class, such as the Geiger bros., Jimmy Hays, Hobart Taylor and others. There was also quite a number of young men who worked around at various businesses, who were quite active in all the amusements of the place. These men and the larger boys of the school used to play town ball (the predecessor of baseball) in the public road just south of the Colver house and barn, or between there and the brick store. Also we played "prisoner base," which developed many good runners. Among the most active of these men were the Bishop brothers, Dan & Wallace, Ab. Giddings, John Coleman, Wm. Griffin, Wm. Burns (Big Bill we always called him, to distinguish him from his half brother, or rather his stepmother's son, whose name was Wm. Williams). There were many others whose names I do not now recall. Of other citizens of the town who were well known, though not in the athletic field, were several who took an active part in the debating society that was organized and maintained during the period that O. Jacobs taught school, and lived for several years thereafter. Among the big guns of the club as orators and logicians were Jim Davenport, O. Jacobs, Sam Colver, Dr. Minear and Mr. Arundell, who lived on his donation claim north of the Thurber claim (which was afterwards the Rose farm). To these seasoned debaters was occasionally added one or more of the Geiger boys, Charley Hoxie (who was a pupil of Jacobs) and James Neil, who also attended the last of Jacobs' school. Occasionally some of Jacobs' younger pupils were persuaded to attempt to defend some very abstruse questions such as "Resolved: That pursuit is more satisfying than possession" or "That the works of art are superior to the works of nature" and many other old and oft-debated subjects. But as a rule, us younger orators would just merely succeed in stammering out a very weak and incoherent apology for not having prepared ourselves, and sit down much relieved. No small part of the social activities of the village was that played by the matrons of the place. No ball or social party could be a success without their active aid. The few budding young women were so entirely monopolized by the bachelors of various ages and qualities that the growing boys and young men would have been entirely left out in the cold had not the matrons taken pity on our forlorn condition and sought us out as partners in the dances, where we usually congregated to gnash our teeth in impotent fury at the bearded men who were swinging our girl sweethearts around as though they belonged to them. I remember very distinctly the first time I ventured onto the ballroom floor to dance. I was fifteen years old and as bashful and self-conscious as a lad of that age ever was, and was ever hanging around where a public dance was being held--not to dance, I was too timid to venture on the floor--but to nourish my jealous feelings over seeing the girl on whom my puppyhood love had been fixed, but who had informed me after three years of constant devotion that I was too young for her any longer, that she was "a grown woman." But yet, not having recovered sufficiently to look for and love another, I was watching through green haze to see some other fellows usurp her favors. There was a cotillion being formed when Hanna McCumber, a matron of 35 or 40, and quite buxom, came to where I was standing, caught me by the arm and pulled me out on the floor, saying, "I know you want to dance, but you never will unless someone drags you out." After looking around I found the three other ladies on the floor were matrons of my acquaintance, and as they all assured me that they would see me safe around, my stage fright in a manner left me, and by the time we had went through the first figure my assurance began to return, and after the three figures were danced I was confident that I could go through all right. The matrons who assisted through my maiden dance were Aunt Huldah Colver, Mrs. Estes, Mrs. Burns and Aunt Hannah McCumber (afterwards Jones, as her third husband). Her first husband's name was Gilson, at least she had a son who went by the name of George Gilson. McCumber, her second husband, was never much known, as he seldom ever visited her, only once at Gassburg so far as I know. He was a seafaring man, spending most of his time on long voyages and leaving his wife to amuse herself as best she could. He was a large, very dark man with bushy black hair and beard and eyes [and] wore a pair of large earrings, was a truly piratical-looking man who one could easily visualize as capable of ordering his hapless prisoners "to walk the plank." Aunt Hannah, as she was called, was one of the well-known Hoxie pioneer family, sister of George, James and Charles Hoxie. They came from the New England states near New Bedford, I think, and the father was an old sea captain. What became of McCumber after his visit to his wife as related above was never known, but it is related that several sums of money came to the post office directed to Hannah McCumber, which she refused to receive. And some time later she obtained a divorce and married a Mr. Jones from Hornbrook, Cal., who was supposed to possess some property. Whether Aunt Hannah died in the little town I know not, as I lost record of many when I entered the service. Of the other matrons, Mrs. Estes, who came there with her husband and son Logan about 8 or ten. He went north on the gold craze of 1861 or '62, and I heard nothing more of him. [omission--due to Stearns' editing of Hannah McCumber's story, as mentioned in the next letter below] excitements of that excitable era, and left her to support herself and son, which she did by sewing The Dr. Minear of whom I spoke as one of the debating chiefs, who practiced for a number of years and also kept a drug store for a while, was one of her permanent boarders. Mrs. Burns was the wife of J. P. Burns, who lived east of the road and north of the Lindley mill and I think died there. His son by a former marriage was nearly the same age as Tom Reams, while Mrs. Burns' two children by a former husband, William & Lucinda, were just about a year older than Lew & Belle Colver with whom they were almost inseparable chums until death and marriage separated them. The girls were each called Sis by the parents and associates, so it was common to refer to them as the two sisses. Two other girls whom I should have mentioned as attending the school of early day[s] were Sarah Blue and Belle Livingstone. The latter was not a permanent resident of Gassburg, her people living near Table Rock on Rogue River. The former lived in the village with her parents. A brother, Johnny I think they called him, attended school later on. Sarah Blue later married a man by the name of Edward, a pretty good man. Belle Livingstone married a man who was later convicted of stealing stock and fled the country. She followed him up, and their whereabouts I never learned. An incident happened in the early part of the gold period that was rather amusing though somewhat tragic. An unmarried woman of about thirty-five who had settled into the community from no one knew where and who did all kinds of domestic work for a living, and who had with her a son of about 16 who went by the name of Frank Merrill, was married after a very brief courtship to a cobbler who had but recently set up shop in the village. This man went by the name of Bowers. Did not have any particular recommendation in the way of good looks or pleasing personality; he simply seemed to have dropped in there from somewhere, and without knowing his given name he was dubbed Joe Bowers, from the catchy song of that title. Either because it was embarrassing to the lady to remain without any other than her maiden name or as a desire to have a home of her own, which the newly arrived shoemaker doubtless promised her, a match was speedily formed between the two and immediately, to celebrate the event, Bowers got beastly drunk and conducted himself in so shameful a manner that a party of indignant citizens waited upon him, tossed him in his blankets awhile, then dumped him into the millrace nearby, and so effectually did they scare the fellow that he folded the robes of night around him and departed into the unknown. The newly made bride did not grieve for long, but soon after married another shoemaker, an old miner and bachelor whose claim adjoined that of Sam Colver's on the south & west. He was always known as Dad Little, and his wife as Aunt Lillie. She made an excellent wife and neighbor, and in spite of her earlier mistakes lived to be respected by all who knew her. There were many changes in the years between 1855 when the blockhouse was built and the commencement of the Civil War. Martha Colver married a man by the name of Cisley, who was a sort of horse trader and sport, a good dancer, and quite popular with the girls. Hiram Colver was very much opposed to the match, not only because he thought Martha was entirely too young, I think only 15, but because he did not think Cisley was a very desirable son-in-law. But Aunt Maria doubtless thought it a pretty good match, besides it would leave her a less number of girls to look after, so the two were made one in the old log house. Uncle Hi in the meantime shouldered his rifle and went up Wagner Creek hunting, thus silently manifesting his disapproval of the entire affair. He only lived a very few years after the marriage. Martha Reams married another sporty man about the same time, Ed Askley, who took her up to the northern mines with him. She did not remain long up north, but soon returned without her charming partner. What was the trouble she kept to herself and several years later married a bachelor, a German by name Joseph Rapp, who though quite a number of years her senior was a quiet, industrious and thrifty fellow, who bought the Thornton place on Wagner Creek, where he followed gardening with good success up to the time of his death some fifteen or twenty years ago, leaving his widow and a son Fred, who still owns the place with some added lands. Martha, after several years of widowhood and invalidism, passed away some few years ago. Mary Scott, who was of about the same age as the two Marthas, married a horse trader and horse racer named Johnson, who died a few years later leaving one son, Calvin. Some time later she was courted by one Dan Hopkins, a bachelor of a speculative disposition, who later left her to become a mother without the forms of marriage. Her son by him is yet living and has always borne the name of Al Hopkins. Mary soon afterwards married George Baily, a very insignificant young fellow whose principal accomplishments were the consumption of whisky and tobacco, though he did work a little sometimes. He bought a place on Jenny Creek formerly owned by James Purves, and here they lived for many years, keeping travelers and making and selling sugar pine shingles and shakes. Here they reared quite a large family until, worn out by hard work and the discouragements of a hard and prosaic existence, she passed over into the beyond, which could not prove worse than she had found life here. About the year 1859 or '60, Uncle Sam Colver went back to Texas to dispose of some land he acquired there during his adventuresome younger days, after selling which he went up into Canada and invested in some French Canadian and other breeds of horses, coming across the plains with them in 1860. He had some thirty or more of fine mares, and some five or six stallions of various breeds, among them the Norman heavy draft horse, the "Coeur de Leon" or Lionheart, a Blackhawk trotter, an iron grey and one or two others, but losing his most valuable animal, one that cost him, so he said, $2500 on the chair. He also brought with him several fine mules, one pair of very large ones he called Jack and Barney pulled his camp outfit across the plains driven by a man he hired in the East for one year for $300. John Wagner was the man's name, and he was one of the most faithful and industrious hired men I ever saw and was the mainstay of Colver's for many years or as long as Uncle Sam would pay him enough to keep him. It was soon after his return from Canada that Uncle Sam saw a chance to make some money by taking a lot of horses and mules up to the northern mines and running a saddle and pack train from the mines to the nearest source of supply. Leaving Wagner in charge of his farm, he took quite a bunch of animals up to the mines where he operated a saddle train for the greater part of a year conveying miners to and from the mines, and sometimes carrying gold out. As there was a very dangerous gang of outlaws infesting that region at that time who, when not running the many gambling dens that infested every mining camp, were waylaying miners who were going out of the country to invest their gold, or they would swoop down on isolated claims and hold up the miners, rob their cabins or sluiceboxes, steal horses, and commit all kinds of deviltry. Uncle Sam was knocked down and robbed at one time, the robbers leaving him for dead, but he was only stunned and managed to crawl to safety. He returned home shortly after, but if he brought any money with him I never heard of it. A vigilance committee later hung or drove away most of the outlaws, some of whom were even elected to protect the people, but joined the gang for profit. One of the men hung there was a former resident of Gassburg, Alexander Carter by name. He was one of two brothers who used to do most of the fiddling in the early-day dances. George, the elder, a medium-sized man about 35 or 40 years old, married Lucinda Low shortly before the John Day mining excitement, which took away many young men besides the Carter brothers. Alex Carter was a fine-looking man, standing six-feet-four, slender and straight, was handsome and a veritable Beau Brummel among the ladies. He had courted Lucinda Sterling, who lived with her mother and two brothers west of Gassburg, but later in the village itself. The elder Sterling, Jim, was a prospector and miner, not at home much. A younger brother, I do not remember his name, nor what became of him. A man by the name of Al Lee cut Alex Carter out and married Lucinda, which seemed to make him more reckless than ever. He was always fond of liquor, and followed bartending and gambling mostly, but no one of his former friends, and they were many, for despite his wildness he seemed to be good-hearted and was sociable and pleasant, ever dreamed of his undertaking the life of a highwayman. Lucinda Carter, after her husband went up north, joined the church during a great revival at a protracted meeting in Gassburg, which was conducted by Rev. Stratton, a very eloquent Methodist divine from Eugene, and both during the continuance of the meeting and for some time afterwards was a very frequent visitor to the house where his convert lived, and less than a year afterwards there was a scandal and a church trial of the Rev. Stratton (who, by the way, had a wife and family in Eugene), but as usual in such trials, the preacher was exonerated, or whitewashed, while the woman carried the perfect image of the reverend Stratton in her arms. The husband never returned, and after a few years she moved away, as did her father's family. I do not think the Davenports, excepting John, made Gassburg their continuous home, as Tim, or the doctor, with his wife and child had a farm at Silverton in the Willamette Valley, and came up to Gassburg to spend the winters for several years. Ben Davenport, with his mother and sister, used to live just a little ways west and north of Colver's, and Ben went to school to Jacobs until after his sister Lucinda married him. I do not remember whether Aunt Sally Davenport lived in the village up to the time of her death or not. I rather think she and Ben went down to Silverton, and that she died there. Florinda, Tim's first wife, spent several winters in Gassburg and was a very frequent and welcome visitor at my father's house. Ora, their only child at that time, was about four or five years old. Homer and another boy were born afterwards, and I never saw the younger one, nor Homer, until the L[illegible] Fair. Mrs. Effie Taylor Chapter 4

In 1860 there

was quite an influx of people to the town of Phoenix, for that fall

came the tribes of Barneburg, Lavenburg and Furry, as well as several

others, who became permanent residents, besides many more who were

simply some of the flotsam and jetsam of the floating population who

come and go with the tide of prosperity or adversity, and whose

presence or absence never create much of an impression upon the society

in a community.

Fred and Wm. Barneburg had been among the early donation claimants on the east side of Bear Creek near the Taylor and Mathes claims. They had come to the country in the rush to the Cal. gold mines and later located claims here, leaving their families mostly in Missouri, I think. In 1859 they went back after them, and in 1860 brought them across the plains to Gassburg. There was the old lady, the mother, and besides the families of Fred and William there was John, a tailor by trade, with his family; the unmarried brothers Aaron and Peter (a cripple) and I do not know if there were not an unmarried sister or two, besides Mrs. Lavenburg and Mrs. Furry. There was Uncle Dan Lavenburg, and a nephew Augustus Lavenburg, and possibly more whom I have forgotten. John started a tailor shop; Dan started a restaurant and notions shop selling beer and, maybe, something else. His wife, Aunt Lizzie they called her, was a famous cook and started a boarding house which soon became famous as the best between Portland and San Francisco. It was not long before the stage passengers took their meals there, as Harve Oatman's wife died about that time and there was no one to keep up the hotel. Mrs. Oatman left a young baby and three boys older; the eldest, Bertie, being then about 8 years old. Frank and Homer came next in order, and Elmer the baby was raised by the Root family, who came into the valley about the same time as the Barneburgs and rented the Wagner place. Mr. Root was a singing master, and his entire family were musical. The eldest daughter married a tinner by the name of Reeser soon after reaching the valley. Annie, the next daughter, married Ole Gunnison, a carpenter, a few years afterwards. Charlie, the youngest, was about the age of Lewellyn Colver, and was a very nice, pleasant fellow. He took up a claim next to that of Lew C.'s and mine in the Klamath country, batching with us for a year or more when he contracted tuberculosis and died in about a year without completing any title to his land, and as none of his people cared to take it up, it was occupied by another party. Charley Root was in love with one of the Shook girls, a family who came into the valley in 1860 and who rented the Hiram Colver farm. There was quite a family of them, John, Mary, Newton, Hattie, Rhoda, David, Will, Peter and Ada. They went out to the Klamath country and located in 1869, and three of the boys and the youngest girl live there yet. Mary, the oldest girl, married James Sutton, who was a former editor of the Jacksonville Sentinel. Hattie married a man by the name of Parker [whose] residence was in Washington Territory or state. Rhoda went to Jacksonville to work for some Jewish family, took up with a Jew, went bad and followed the life of the red light district. Peter died at about 20 years of age. Dave and Will never married, and John married a dressmaker in Portland, when he was past 40, and his wife was nearly as old. Each thought the other had money, and each was resentful when undeceived. They led a cat-and-dog life; she finally left him after getting some hold on his property when they had a lawsuit over it, which is unsettled as yet. Newton came over into the valley here some thirty-five years ago and married one of the Payne girls, who was a widow. After a few years they separated and both remarried. Newt, as he is generally called, owns some property here in Ashland and lives here now. Al, Lee and family lived in Gassburg for a number of years not far from where Dan Lavenburgs lived; they afterwards went over to Siskiyou Co. where he owned and operated a mine on Greenhorn Creek for a number of years. The Davenports were living in Gassburg when Olive Oatman was rescued from the Indians, and she lived with her relatives there for a time. She and Florinda, Tim's wife, were great chums, and Olive gave Mrs. D. and several other women friends exhibitions of her swimming prowess in Bear Creek, teaching some of them swimming lessons there. I do not remember whether Aunt Sally D. died in Gassburg, or whether she died after going down to Silverton with the Dr. and his family. The Davenports were cousins of Uncle Sam Colver's I have always understood, but whether related on Grandfather or Grandmother Colver's side I either never knew or have forgotten. Grandma Colver was a Currey, and a nephew of hers, George B. Currey, who, by the way, was the colonel of the 1st Oregon Infantry, after serving as captain of a company of the first Ogn. Cavalry, used frequently to visit the Colvers in Gassburg. George B. was quite a politician, and occupied several prominent positions in the state government at various times. Tim Davenport was a well-known figure in Oregon and, though no politician, was a very able and wise councilor in all matters of public policy. He was a member of the legislature several times and always took a leading part in shaping legislation and in discerning and opposing graft and trickery in legislative matters. He was clerk of the State Land Board for a number of years, and selected much state land that inured to the state under various acts. Being a practical surveyor, his work was accurate, and very valuable in such matters. While living in Gassburg he taught a class in shorthand for a while, just to put in his time. I was a boy of about 15 years when I first became acquainted with him, and he seemed to take quite a liking to me. Knowing that I was desirous of obtaining a college education and, perhaps, realizing how impossible of attainment it was for me there, he offered to give me the opportunity if I would live with him, help him on the farm winters, and attending school. In the summers he would pay me big wages assisting him in his surveying contracts, and send me to college as soon as I was far enough advanced to go. That was a very fine offer, but situated as I was, my older and younger brother left home being both dissatisfied with farm work and farm life, had I accepted his offer it would have been disastrous to my father's business, besides I could not accept without the consent of my parents. All the above is personal, and unrelated to the narrative, but I mention it to explain that my friendship for the Davenport family had a very stable foundation, and the fact that the Dr. and I were fast friends and frequent correspondents up to near the time of his death will not be surprising. Meanwhile the Civil War was drawing near, and the news of the firing on Fort Sumter sent a thrill of anger through the hearts of all true patriots, and the necessity of prompt action on the part of all true patriots required that this remote part of the great nation do its part in the defense of the Union. Remote as we were from Washington, with no communication except by way of vessel by way of Panama, or around the Horn, it took from six weeks to two months for news to reach us, and much might happen in that time. Although our frontiers were occupied by hostile Indians who were only held in subjection by the military forces stationed at the various frontier posts, the necessity of having all available troops sent to the front necessitated the raising of volunteers to replace the regulars now guarding us, that they might assist in putting down the rebellion. A call was immediately issued for the raising of a full regiment of cavalry, and Jackson County was required to furnish one company. Recruiting offices were opened, and the erection of log barracks for their accommodation was commenced in the early fall of 1861. The site selected for the camp was in the woods about a mile southwest of the town of Gassburg, on Coleman Creek. In a short time the log barracks, stables for the horses, officers' quarters and storehouses were completed, for as fast as volunteers were recruited they were set to work. As soon as the barracks were habitable the cleaning of the ground for drilling purposes followed, and it became a busy place. Gassburg simply rushed into the proportions and activity of a small city, as all the material and subsistence required to maintain a full company of cavalry with their horses and everything pertaining thereto was of necessity purchased there. The shoeing of all the horses and teams kept the blacksmiths and shops busy. Milt Smith had been joined the fall before or that spring by O. T. Brown, who just came across the plains from Wisconsin, and he was a good smith and tireless worker, though a small man. He and Smith took the contract to shoe the government stock, and it kept them busy from daylight until dark, weekdays and Sundays. Meanwhile Brown took the ague [malaria], which was then the prevailing disease all along Bear Creek every summer and fall. Still, never stopping to rest except when he shook so hard he could not drive a shoe nail, Brown worked until by spring when the cavalry left he was almost a physical wreck. The raising of the company of cavalry in the valley sadly depleted the number of young men in the community, as well as to change the political complexion of the vote. Jackson County for a few years had become quite a strong Republican county, but after the departure of the volunteers, followed almost immediately by a large influx of Missouri bushwhackers who had been chased out of Missouri when Price's army was defeated and scattered the first year of the war, it was for many years Democratic. [This assertion is contested.] Among the young men who enlisted in the first cavalry from Gassburg that I now recall were the following: Hobart Taylor, Jas. Hoxie, Jas. Kimball, Robert Grey, Gus. Lavenburg, Felix & Joseph Peppoon (newcomers) and, I think, John Van Dyke, [and] several others whose names I have forgotten. As the mines were still booming, one or two other businesses that started up during the recruiting of the cavalry still kept up. Henry Mensor, a Jew merchant of Jacksonville, put a stock of goods into the Oatman brick, and Patrick McManus put up a store farther south. S. M. Wait had sold his grist mill to a big German who formerly had a donation claim east of Manzanita [the Central Point area] on The Desert, as it was called [the White City area]. This man's name was Wm. Hess, and quite a character too. Lew Colver used to tell a story of him which was rather funny as well as characteristic of the man. He had purchased some half dozen or more of geese, which swam around in the millrace between the mill and the road, and the owner was very proud of them, calling the attention of his many patrons to his new venture. Someone called his attention to the similarity of the looks of all his flock and suggested that he had been cheated, as they were all ganders. "Huh! Guess I know," quoth Hess, and proceeded to point them out to his critic in the following words: "Now, him been a goose and him been a goose, and she been a gander, and she been a gander," designating a different one every time. But he was much disappointed to find later that his flock did not increase. I forgot to mention a Dr. Hargrave, or Hargrove, who came to Gassburg soon after the flouring mill was built and remained some little time. Mrs. Wait was his eldest daughter, and he had another unmarried daughter, Laura by name, who later married Pat McManus. They afterwards moved to Yreka, where he was engaged in the mercantile business with a McConnell under the cognomen of McConnell and McManus. The head of the farm married the youngest daughter of a pioneer family, Giles Wells; her name was Elizabeth, I think, though she was always known as Bid or Biddy Wells. While I have it in mind I will relate an escapade of hers in Gassburg, wherein the Jew Redlich was the victim. This Redlich was a confirmed ladykiller. He was a slight, waspish-formed fellow, about five feet and a half high, light-complected with a mop of very curly light-brown hair, thick lips which, had his complexion and hair been dark, would have stamped him as of Ethiopian origin. He was a confirmed guitar player and often accompanied his playing with love songs sung in a very melodious and plaintive manner, at the same time rolling his protruding eyes around as though in the throes of colic. He was always very attentive to the ladies, and for years was the steady beau of Donna Colver. In fact, everybody expected them to be married, but from some cause (probably racial and religious) they were not. One day quite a number of young ladies, among them Bid Wells, visited his store when he was engaged in his musical solos, presumably to do some shopping. They got to joking and cutting up when something was said about Samuel's failure to get married, when Biddy remarked that she could not imagine how any woman could think of marrying a trifling little whiffit like him. Redlich spunked up at that and asserted that though he was not as large as some, he was more of a man physically than many larger men. "Pshaw!" said Biddy. "I'll bet I could dust your back for you myself." "I'll bet you can't," said he. "How much will you bet!" said she. "I'll bet you a new silk dress against the price of it," said he. "Done," said she. So they shut the store door against intrusion, and with only the other girls as audience they had their contest. Biddy went away with a new silk dress. How much the other girls got to keep the matter quiet I never learned. But it eventually leaked out, and whether that was the cause of the Jew leaving the country I do not know, but he left the country shortly afterwards and I never heard of his returning. I do know, however, that he would never knowingly meet any of his former acquaintances in San Francisco, where he lived later, because after the war I was in the city when I recognized him when I passed him on the street, and following behind him to a hotel found his name in the register. I left my card with the request that he call on me or give a date when it would be convenient for me to call on him, but never heard from him though I called at the hotel again to learn if he had left any word for me. Another family I had forgotten, or overlooked: They came into the country about 1860, first renting a place across Bear Creek, later moving into the Burg, where Uncle Billy, as he was called, followed shoemaking and mending. His family consisted of himself and wife and four children, one girl and three boys, ranging from 16 to ten years of age. The oldest, Wm. Henry, was a member of the [Siskiyou] Mountain Rangers, a home guard company to which Lew C. and myself belonged in 1863 & 4 and afterwards, also joined the 1st Oregon Infantry, to which we and any other boys of the valley belonged. The Roberts family moved out to the Klamath country in 1869 and located next to the Shooks in Alkali Valley. The girl married James Callahan, a stockman of that valley, and raised a large family, most of whom still live in the Klamath country. James Callahan was sent to the insane asylum many years ago and died there. His widow too is dead, as also the entire family. The boys were all worthless and dissolute characters, and died violent deaths. Quite a number of people who, though not permanent residents, were occasional residents of Gassburg, working in the mines during the winters while there was water for sluicing and at various occupations during the dry part of the year. Among them were Dennis Crawley, and his mining partner Charles Boxley. The latter went to school one or two terms to O. Jacobs. Crawley was sent to the insane asylum about 1860 or '64 and was discharged from there in 1865, going out to Klamath late in 1867, where he stopped over winter with Lew. Colver and myself, where we were joined in January by Charles Root. Dennis died in the asylum some fifteen or twenty years later, having had a recurrence of his insanity or simply another acute phase of it, as I do not believe he was at any time perfectly sane after his first commitment. The Goddards and several others who resided at or near the Burg came into the valley sometime about 1861 to 1863. The Allens, who settled near the Colemans and whose daughter Maria later married John Coleman. A Mr. Ball--given name forgotten--with his two sons, Alfred P. and Rufus, came there about the same time, and Mr. B. took over the tannery that Geiger and others had established, and ran it for many years. He was a Yankee, and a very queer character. He was a small, skinny man, with little beady black eyes, a hawk's beak of a nose, hatchet faced, and a wrinkled leather (russet) colored skin. He was a very pious hypocrite, and notoriously unreliable. About that time came also the elder Thurbers, the father and mother of John, Jack Thurber, or Jack of clubs as he was called. Your mother later came into possession of his donation claim, and was living there when she died. The Thurbers were Vermont Yankees, and all of them original characters. Mrs. Effie L. Taylor Chapter 5

In the fall of

1864, President Lincoln issued his last call for volunteers--three

hundred thousand men, and Oregon was called upon to furnish her quota,

which was fixed at one regiment of infantry and enough cavalry to fill

the depleted ranks of the First Cavalry, most of whom had been

discharged by reason of expiration of their terms of enlistment.

Jackson, Josephine, Coos and Curry counties were assigned the raising of one full company of infantry, and Franklin B. Sprague, the miller in Hess' mill, undertook the recruiting of them with the assistance of I. D. Applegate, who had been in command of the Mountain Rangers, a militia company to which Loui Colver and many others, as also myself, had belonged for nearly two years. Mr. Sprague asked me to join his company and assist him in the recruiting office in Jacksonville, but as I had a wood contract yet uncompleted for Uncle Sam Colver it was necessary to get his consent to leaving it unfinished, which was readily granted, and on the 17th day of November I entered the service, being the first to enroll in the company. On the 19th, three other men enlisted, men returning from the northern mines, having their blanket rolls on their backs. I was detailed to escort the recruits out to Camp Baker, about 8 miles distant over the old hill road by Hamlin's farm. A Lieutenant McGuire of the 1st Cavalry had been sent out to take charge of the old camp and drill the recruits. He had moved into one of the cabins a few days before, and had but a meager outfit for batching, very few supplies of any kind to commence with. I left Jacksonville about 3 o'clock P.M. with my recruits pretty well ginned up, to walk over a rough road eight miles to Camp Baker. What with the bad roads and erratic movements of my recruits, on account of an overload of spirits, it was well after dark when we reached McGuire's headquarters. As there was no bedding for me, and the four had to spread their blankets on the floor, I trudged on to Gassburg and put up at Colver's. That was my introduction to military service, and while I shall not attempt to give a history of that service but just an introductory to that part connected with the old village and those of its inhabitants who went out on the frontier to guard it against Indians, as also to account for some of them since. I have in my possession a roster containing the names of all who joined Sprague's company, and a very brief indication of their careers as far as known. There were 81 names on the enlistment rolls, of whom four only remain alive as far as [is] known. After spending a week or two in the recruiting service, Captn. I. D. Applegate was cheated out of the promised lieutenancy and Harrison B. Oatman was given the commission against the protests of the entire company, most of whom knew and disliked him, a feeling that was fully justified by his subsequent military career. No plausible reason has ever been given for shelving Applegate. Only two plausible excuses or reasons could be conjectured. One, that Oatman was a Mason, as were nearly every state official who had influence in the state. The other that Oatman was indebted to quite a few prominent citizens in Jackson County, and having no position that gave promise of his being able to liquidate in the near future, a military commission promised to place him in a position where he might favor his many creditors in securing future contracts to furnish government supplies, while Applegate was a man of strict honesty and unapproachable in the matter of bribery or favoritism, and his appointment would not benefit them. Oatman did nothing to help raise the company and never could drill it. My brother Newell and cousin Alonzo Williams, to whom I turned over my rental of my father's farm that I might enter the service, also enlisted during the winter leaving the farm without a tenant, and my father had to rent it during the entire time we were in the service. Sometime in January 1865, Uncle Sam Colver came to me and said that Loui was crazy to enlist, and if I would promise to act as "big brother" to him he would consent to his joining the company. Of course I felt very highly flattered by his request, as it showed me that he held me in good esteem, and I trust my promise was faithfully kept. As our company contained many neighborhood boys, some of them pretty wild, and the drilling did not occupy as much of their time as it ought, many of the neighborhood hen roosts and pig pens suffered from night visits of foragers. No one was ever arrested or punished, though the tables in several of the mess houses were loaded with food not issued by the commissary. One man in our company, Stephen T. Hallack by name, would never eat of the foraged provisions and used to remonstrate with the boys against the practice of foraging with great vigor and sincerity. He was a quiet man of about forty years of age, a native of New England, a sincere Christian and of strong convictions. He had a mining claim near Colemans, and had been in that neighborhood several years and was well liked. He met a sad death the winter of 1865 and '66 returning from the valley where he had been on furlough, and froze to death in sight of the fort the morning of April 1st. His was the only death in our company during the nearly three years of our service. I wrote up a full account of this sad tragedy and have the newspaper clipping containing it. Our company marched over the mountain to Fort Klamath by way of Green Spring Mountain in May 1865, arriving there the first day of June. Soon after our arrival Captain Sprague received permission from Maj. Rhinehart, our post commander, to hunt for a more feasible wagon route from the valley than the one opened in 1863 by way of Rancheria Prairie and Mt. McLoughlin when Col. Drew went over to establish the post, as that was almost impassible for wagons, and a vast amount of army stores and supplies had to be transported over there each year. Sprague secured the permission and, securing the services of John Mathes of Butte Creek, they put in about two weeks exploring the range from McLoughlin northeasterly and finally located the route from the Rogue River road near Union Creek across by the Annie Creek gap to Wood River (the present road). Upon making his report of the success of his explorations, Sprague received authority to take twenty or more of his company with provisions, team and tools and open up the road upon the route selected. This was accomplished in about six weeks. When the road was nearly done, orders came for Sprague to take forty men of his company and forty of "C" Company of the First Cavalry with equipment and proceed to Steens Mountain, about two hundred and fifty miles eastward in the Paiute Indian country, to meet there another company of our regiment and build Camp Alvord as a base of operations against the hostile Indians of that region. As Sprague was desirous of having all his men who accompanied him to voluntarily offer to go, he had me go with him out to the road camp to get a list of the boys out there who would volunteer. It was while we were at the road camp that we learned of his discovery of the lake now known as Crater by two of the road crew who were hunting deer a few days before. We found at the road camp a party of four Jacksonville men, having come out to see the new road, and as they wanted to see the lake, they went with us on our return to the fort when, following the instructions given us by the discoverers, we visited the lake, and myself and one of the civilian party ventured down to the water, being the first human beings to reach its waters. As I was the first to reach the water, it was conceded to be my privilege to name the lake which, at the suggestion of Capt. Sprague, I called Lake Majesty. And that was the name by which it was known for several years, or until James Sutton and a party from Jacksonville several years later paid it a visit and, having a canvas boat, visited the island, ascended to its top and finding the depression therein renamed the lake Crater Lake after his return to Jacksonville, where he was editing the Oregon Sentinel, and in which he gave a glowing account of his trip. The lake, no doubt, had been seen before, but never located definitely, nor even a blaze on a tree to indicate its having been visited by white men previous to its discovery by members of our company. Sprague wrote an account of our visit and the name we gave it, which was the first actual location of and naming of the lake, and to the credit of Company "I" is due the addition of this one of the world's greatest scenic wonders; for, had it not been for Sprague's enterprise in searching out and building that road, the lake might have remained today as it had remained for centuries before, unknown. A few days after our return to the Fort from this trip, the boys who were opening the road finished their work and returned also, and the active work of preparing for the expedition to Steens Mountains two hundred and fifty miles out into the Paiute Indian country was under way and within one week was on the road with forty cavalry, forty infantry of our co., three or four army wagons and a train of fifty mules loaded with our equipment and supplies, together with a small herd of beef cattle for the commissary department. Your uncle L. Colver did not accompany us, preferring garrison life as quartermaster's clerk. After near three weeks of rather arduous travel and some few adventures, with no skirmishes, we reached our destination, Steens Mountain, during a terrible sandstorm that obscured the sun and rendered progress against it very difficult as well as painful, the coarse sand being driven by the force of the wind cutting one's face worse than hailstones. We found Company "G" of our regiment already on the ground, having arrived from The Dalles a few days previous, and they were occupying holes dug in the sides of the creek banks which were covered with sticks, brush and canvas to protect them from the fierce winds that seemed to prevail in that country. A very interesting chapter could be written descriptive of that country and of our work there constructing quarters for men and animals, providing forage for animals and wood for quarters, but such hardly comes within the scope of pioneer tales. I will simply add that after little more than six weeks' stay at Alvord, and just as myself and several other "noncoms" of the three companies had constructed ourselves a log house, covered with split rails, grass and mud, the officers discovered that there was not enough provisions on hand to carry the entire force through the winter, hence it was necessary to send a part of the number to the nearest garrison, which happened to be Fort Klamath. They had sent messengers to Ft. Boise and also to Fort K., but had heard nothing from either place, so they decided to start a party of 25 men each of our co. of infantry, "C' Company, and 12 men of "A" Co. Cavalry, with the 50 mules that were hired at Fort K. to transport our supplies hither, on the backward journey to Fort K. And as the supply of officers remaining at Alvord was limited to four, Sprague having returned to Fort K. nearly a month previous with dispatches and had not returned, so it was feared he had been killed by Indians, they put me in charge of the outfit, and we started back about the 10th of Sept. without a tent or shelter of any kind and only 20 days rations. It was rather a peculiar situation, myself, an infantryman, in charge of such a force of men and animals, 37 cavalry men, mounted, and 25 infantrymen to keep them company. However, we made the journey in 15 days, having experienced several rainstorms and arriving in a severe snowstorm with about a foot or more on the ground. We ate our last food the morning before we arrived, Indian dogs having raided our camp while about sixty miles up Sprague River and eating up our bacon. We found the fort almost in a turmoil over the ration and work problem, and our advent only increased the discontent which resulted in what we called the "bread riot," an account of which was published in the National Tribune last fall, and which I will send you. In my next chapter [I] will give you a brief acc[ount] of how L. Colver, Robt. Clark and myself took up claims in Klamath country, established a road and some incidents in the life and history of Uncle Sam Colver, who was more or less identified with that country for years. Mrs. Effie Taylor Chapter 6

The winter of

1865 and '66 passed at last after its rather strenuous times, and in

the spring came orders for all the cavalry at the post to proceed to

Vancouver to be mustered out of service, leaving just "I" Company with

the major in command of the post and Lieutenant Oatman in command of

the company. In little less than a month the major also was ordered

away to be mustered out, and he had scarcely gone when our Captain

Sprague, with four of our company who had been with him out at Camp

Alvord, returned to Klamath and took up the usual routine of post duty

with occasional forays out in the Indian country.