|

|

Zany  Zany Ganung 2

May 1861 Thursday

I heard that old Joe Lane is expected in Jacksonville to preach secesian to night but I guess there are to many union loving men to allow him to proclaim his treasen here in the valley they tried to hoist a palmeto flag in Jacksonville but it was soon torn down. Expluribus gloria Diary of Welborn Beeson

Mrs. Zany Ganung was born in Madison County, Ohio, February 15, 1818, and emigrated from Illinois to Oregon in 1847. "Southern Oregon Pioneers," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, July 15, 1882, page 3 In Search of: Zany Ganung

One of Jacksonville's favorite legends

is the

familiar story of Zany Ganung and the rebel flag; the story is retold

and embellished every time a Jackson County history mentions the Civil

War. The legend, as it has come down to us, distilled by 130 years of

retelling, was once again retold earlier this year in the Table Rock

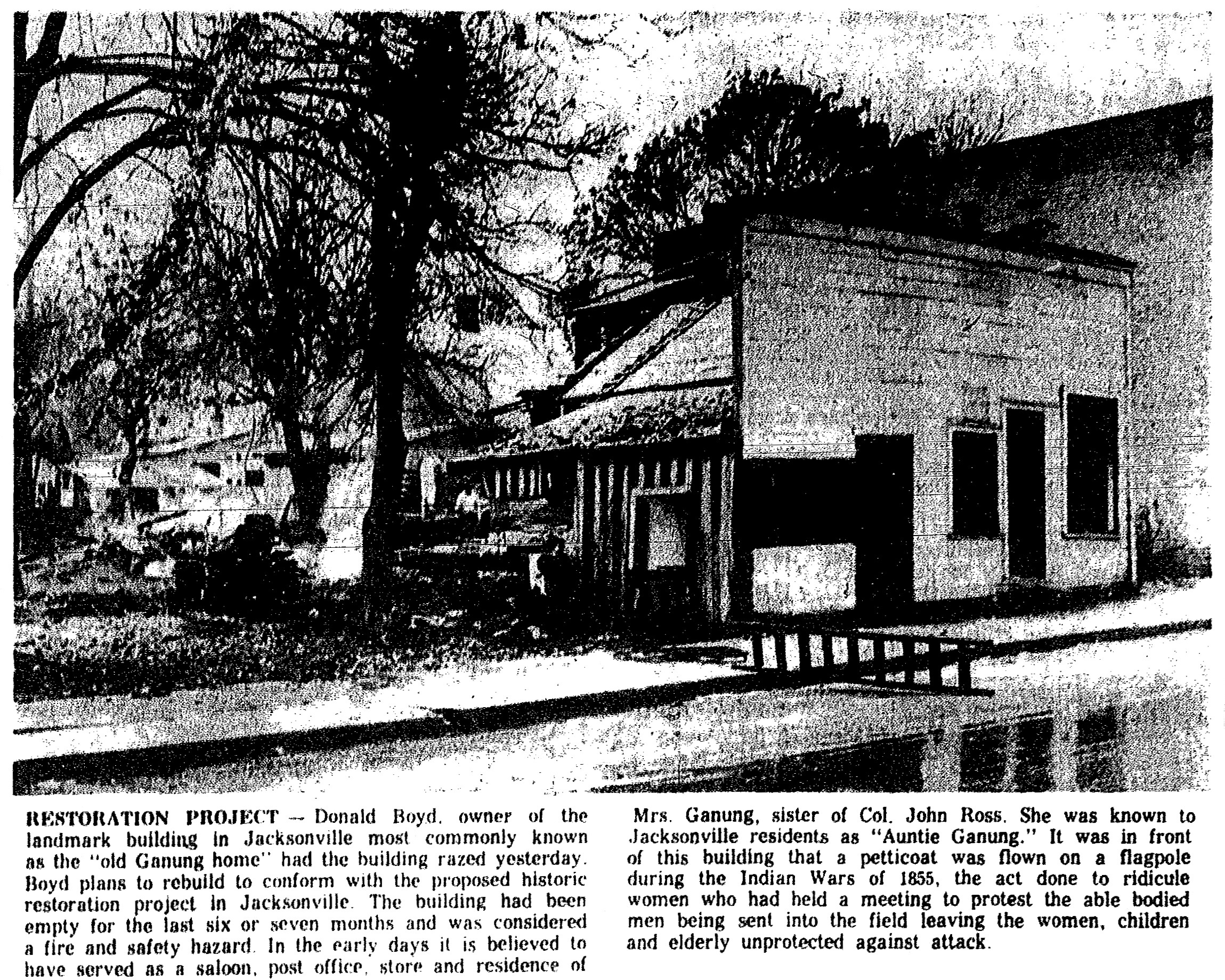

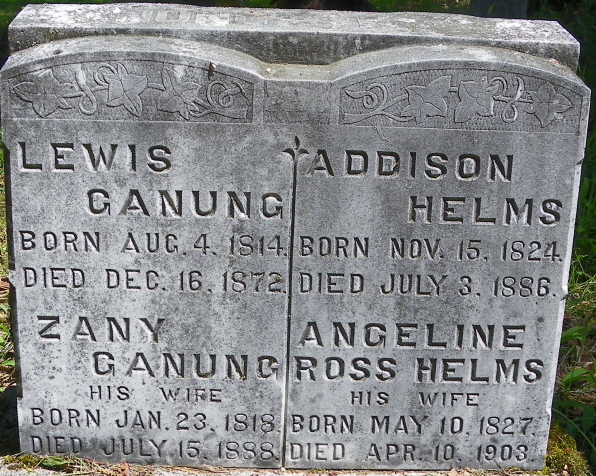

Sentinel:by Ben Truwe Local legend in Jacksonville includes the tale of Zany Ganung, who awoke one morning* to find a Confederate* flag flying over the town. She promptly got her hands on a hatchet* and chopped down the offensive emblem. Southern Oregon clearly included more Confederate sympathizers than was common in other parts of the state*(1) The most embellished version of the legend--with the addition of amazingly little factual material--was published twenty-five years ago by Francis D. Haines, Jr. in his Jacksonville: Biography of a Gold Camp: There is one famous story of Jacksonville and the Civil War. It is the story of how "Aunty" Ganung lowered the Confederate* flag that flew for a time on California Street in downtown Jacksonville. As we have seen, Jackson County was heavily Democrat.* There was a large body of opinion in the summer of 1861 that endorsed the idea of recognizing the Confederate States as an independent nation.* (Colonel T'Vault endorsed the idea as a precedent for establishing a Pacific Republic, but he doesn't count.) . . . The only positive action of a Southern conspiracy in the region occurred in Jacksonville one night, apparently in 1861. Someone ran a Confederate* flag (design unknown)* up a flagpole in downtown Jacksonville and tied the halyards. Dawn revealed this emblem of armed revolt against the United States. And there it stayed, fluttering in southern Oregon's balmy breezes. "Aunty" Ganung, wife of a local physician,* Dr. Louis* Ganung, could brook this insult to her native land no longer Since the men of the community were not manly enough to take action, she determined to do so herself. Arming herself with a revolver and an ax,* Aunty sallied forth to the fray. Her brother, Colonel John Ross, never went forth against the Indians with more grim determination than Aunty displayed on this occasion. Looking neither to the right nor to the left, she marched down* California Street to the flag pole that bore the offending emblem of sedition and rebellion. Arriving at the pole, she hefted her ax,* put down the revolver and set to work. An ax was not altogether an unfamiliar implement in the hands of Aunty Ganung. If the doctor were away for a time on a difficult case, someone had to chop the wood for fires. Vigorous blows of the trusty blade soon brought the pole crashing* to the ground, dropping the flag in the dust of California Street. It was an appropriate location for it. The determined patriot then removed the banner from the halyards, wadded it up and rolled it in her apron. Without a glance at the bystanders, she picked up her revolver, shouldered her ax and set out for home with the air of one who has labored long and well for the right and is conscious of a job well done. It was not "chivalry" that prevented an attack on Aunty during her labor of patriotism.* Whatever doubts the onlookers may have had of her marksmanship with the revolver, they had absolutely no doubts as to her willingness to use it. And there were no doubts at all concerning her marksmanship with the ax or her equal determination to utilize it on any obstacle in the course that she had ordained for herself that morning. No banner of sedition and slavery ever waved again in Jacksonville during the Civil War nor was the flagpole ever replaced.* The pointed stump remained a noted monument to Aunty's patriotism for many years until a small boy, playing, fell to the ground and fatally pierced his skull on the point of the famous stump.*(2) My own interest in the Zany Ganung story was seized when I stumbled across this version, as related by Ranger Lee Port of the Applegate Ranger District forty-six years ago, in 1945: The first brick building in Oregon was built by David,* the brother* of Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy. He was one of the partners, Maurey [sic] and Davis. They came to mine, and were working in red clay and decided to go into the brick business.* They also ran a store and remained in business until the Civil War, when Maurey left for a time. When he returned he found the Confederacy* flag flying in front of the store*. He said he would cut it down, and Davis said he'd shoot the man who tried it. Finally a woman cut the pole down. All of this started a row and both left--David to join the Confederacy* and Maury to join the Union.(3) Wow, what a story! If only half of it is true, this event has everything; it's almost cinematic: famous personalities, threats of mayhem, acts of bravery, even a gory denouement. And the farther back I go for source material, the more interesting it gets. It shouldn't be hard to research--one quick trip to the Southern Oregon Historical Society research library should clear everything up. So began a months-long library odyssey in an attempt to refute or substantiate every "fact" asserted in over a dozen versions of the Zany Ganung story. That first trip to the library turned up what was then the oldest known account of Zany's story, in her obituary, prepared by the Southern Oregon Pioneer Association, a mere twenty-seven years after the fact: Mrs. Zana Ganung, relict of Dr. Lewis Ganung, died at her residence in Jacksonville July 14th, 1888 at 1 OClock P.M. of Nervous disability, aged 70 years, 4 months and 29 days--The deceased was the twin Sister of General John E. Ross, and was born in Madison County, Ohio, February 15, 1818--With her parents she removed to Fountain County, Indiana in 1828--And to Cook County, Illinois in 1833--She was married to Dr. Lewis Ganung in Geneva, Illinois in 1840. After a few years' sojourn in Iowa, she crossed the Plains* with her husband to Oregon in 1853. . . . In disposition she was gentle, and unassuming, prominent in her religious character, with a strict consciousness, combined with a quiet hopeful cheerfulness. She was one of the excellent of earth, worthy to live, but ready, and willing to die--In the early days of Jacksonville Auntie Ganung, as she was familiarly called, was a general benefactress--The latch string of her Cabin door always hung on the outside--As the emigration dragged into our midst dust-stained travel worn, and foot store--Auntie was always among the first to extend the hand of Friendship, and give them kindly welcome; we have known her to divide her last morsel among the sick and destitute; kindness seemed to be the greater part of her make-up, the toddling infant never passed her door without a kind word, and a smile of welcome . . . .Well do we remember the day when Auntie Ganung put her ax on her shoulder, her revolver in her belt, and faced hundreds of angry men, demanded and rescued our National Flag from desecration*--The immortal name of Barbara Fritchy of historic fame was no more daring a deed, or showed a more Patriotic Spirit than did Auntie Ganung on that memorable day.(4) Uh-oh. What happened to the part about chopping down a rebel flag? It was beginning to become apparent that substantiating a 130-year-old legend wasn't going to be easy. Little more is known of Zany than was recorded in her obituary. The Ross family records her given name as Mary; Zany (formally Zana) was a family nickname she adopted describing a headstrong character still evident in Ross family women.(25) The Ganungs had lived in Salem before moving to Jacksonville; Zany operated a millinery shop in partnership with the wife of lawyer (later General) Eli M. Barnum(26) In the only newspaper story mentioning Zany written before 1932, Zany and Mrs. Barnum are listed as passengers on the maiden voyage of the steamer Gazelle on the Willamette River, a pleasure excursion attended by "the beauty and the chivalry of Salem, Takenah and Corvallis."(27) After adjournment of a general meeting of the passengers, "a spirited Women's Rights meeting was convened. . . . The meeting passed off with great eclat and the speeches were vehemently cheered."(28) Perhaps coincidentally, a women's meeting of a different nature was also convened in Jacksonville after Zany's arrival in Southern Oregon. When local wags ridiculed the meeting [what meeting?] by hoisting a petticoat on the town flagpole, two unidentified women, armed with pistols and an ax, braved a crowd of men to retrieve it.(29) It's tempting to assume that, with what we know of her character, Zany was involved in all of this. Certainly the events described in her obituary seem to be a confabulation of what has become known as the Petticoat War with the rebel flag incident. At any rate, it's pretty safe to assume that if Zany wasn't the instigator of the earlier event, she probably wished she had been. And we can be pretty sure that when Zany saw a rebel flag in Jacksonville six years later, she drew upon the knowledge of the earlier incident. The editor of Jacksonville's Oregon Sentinel, until only weeks previously a Copperhead paper, did not mention the flag incident. But on May 19, 1861, he did print this short notice; "LIBERTY POLE.--A new liberty pole is to be raised in a few days to take the place of the one on California street, opposite the United States Hotel. We understand that a nice flag has been ordered from San Francisco, with which to ornament it."(8) And then on June 6: "FLAG STAFF.--A new flag-staff was raised during the week on the corner of California and Third Street, and from it floats that beautiful banner, the emblem of our Country's greatness."(9) But despite the many volumes of Oregon histories and hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles written, no account of the rebel flag incident was recorded until 1932, when the Medford Mail Tribune published the following brief article: Rattlesnake Flag Over Jacksonville Briefly June 11, 1931 there appeared in the Oregonian the following: "'At Jacksonville, southern Oregon, there are two flags raised--the glorious old stars and stripes and the palmetto and rattlesnake flag' said the Oregonian on June 11, seventy years ago." This reminded some of the older residents of the old mining town of that day seventy years ago when a whole community held itself tense and waiting from daylight until late afternoon. It was never known whence the flag of the Confederacy came nor by whose hand the pole was erected and the flag flown, but there it was at daybreak across the street from where "Amy's Place" has been now for so long.(19) No one ventured to remove it for fear of starting a little civil war of its own in this little western town; men spoke in whispers and many came to look at it and wonder by whose hand it had been raised. It so happened that Dr. Ganuny [sic], and wife who was known to all as Zany Ganuny, had spent the night and most of the day with a very sick patient. Late in the afternoon, tired and exhausted, Zany returned to her home for a brief rest and saw for the first time this strange flag floating in the breeze across the street and almost opposite her own door. She is described by those who knew her as a large dignified woman, unusually good looking and always wearing a crisp cap with perky lavender ribbons in it. Without word to anyone she entered her home, to appear shortly with a hatchet in her hand. Looking neither to right nor left she crossed the street and began to chop the pole down. Many watched her, but no one spoke, and as the pole began to sway Mr. Love stepped forward and held the pole to keep it from falling on her. As soon as she had severed the pole Zany Ganuny untied the flag, crossed the street, entered her house,closed the door and burned the flag. The end of the pole left in the ground remained here for years until the unfortunate accident which resulted in the death of Henry Overback [sic], after which it too was removed.(20) This article is the father and grandfather of all versions of the Zany Ganung legend. The clipping in the files of the Southern Oregon Genealogical Society credits its source as Alice Hanley, as told to reporter Jane Snedicor. Alice Hanley wasn't old enough to have been an eyewitness, but I can find nothing else to discredit this account of the events of that day in Jacksonville. {The misspellings are simple transcription errors.) The language (unlike later versions) is precise as to where the flagpole and the doctor's office were, the physical description of Zany itself, the name of a man who stepped forward to help her. Nothing more is known of Zany's actions on that day. I have found four other early accounts of the rebel flag in Jacksonville; none of them mentions Zany or even the fate of the rebel flag. The 1861 Oregonian article, referred to by the Mail Tribune, in its entirety: THE PALMETTO FLAG IN SOUTHERN OREGON.--A friend writes us: "I have just returned from Southern Oregon. While in Jacksonville I saw two flags raised--the glorious old Stars and Stripes, and the palmetto and rattlesnake flag. About the palmetto flagstaff there were a few staggering drunken men, who were hardly sensible of what they were about, and who were put up to do what they did by others who were in the shade; while the flagstaff of the Union was surrounded by a large crowd of intelligent and well-appearing citizens, and a goodly number of ladies. The ladies raised the flag, and as it spread to the breeze, there went up such a shout as never was before heard in Southern Oregon. Union is the strong prevailing sentiment here. There are but few Laneites who would glory in the downfall of this great Republic."(21) On May 8, 1861, an unnamed Jackson County correspondent wrote to the Oregon City Oregon Argus: The vagabond ruffian class have been hoisting the flag of mutiny in Scott's Valley and Jacksonville. The disunion flag was raised in the latter place by a band of which Charley Williams (the man who killed Butterfield) is the leader, and who is now under bonds to answer an indictment for murder. The good citizens of the town tore down the treasonable flag as soon as it was discovered, for it was put up in the night.(23) After the turn of the century, J. S. Howard, first mayor* and self-styled "Father of Medford," wrote: John [sic] T. Glenn conducted a store in Jacksonville at that time. His clerk was a Copperhead. When news of the war was confirmed, the clerk ran up a flag of secession, over his employer's store. Again excitement reached fever heat, as the report quickly reached the miners in the hills. Soon, however, miners in their rough garb and with grim visages came rushing down from every canyon and claim until about 800 of them had reached the town, intent upon making short work of the rebel bunting, when suddenly the flag of the secessionists disappeared.(22) History is written by the victors. The only surviving rebel account of that day is preserved in an unpublished 1931 master's thesis: At one time during the early days of the Civil War southern Democrats gained control in Jacksonville. Although this lasted but a short time, the pro-slavery men proudly boasted that for a time the Stars and Bars* floated over Jacksonville as a southern city.(24) In the years since the codification of the legend with the 1932 Mail Tribune "Ganuny" article, there have been well over a dozen Zany Ganung/flag versions in print, all derived solely from that article and the author's imagination. The storyteller's imperative to embellish and the journalist's imperative to paraphrase have created several enduring contradictions and inaccuracies: And what of poor Henry Overbeck, the "small boy" who was playing and "pierced his skull" years later on Zany's handiwork? It seems that the "playing" may be the only accurate part of this sequel to the Zany Ganung story. Henry was nearly seventeen and a half when he died (10); the Sentinel reports his death as follows: MELANCHOLLY ACCIDENT.--On Wednesday evening, as Henry E., the only son of Dr. A. B. Overbeck, of this town, was pushing his father's sulky before him, on California Street, he accidentally ran it against the post at the Express Saloon corner, and so great was the force of the rebound that one of the shafts struck him on the side and inflicted injuries from which he died on the subsequent evening. The young man was respected for his quiet deportment and manly qualities, and had he been spared, would have been a useful member of the community. The blow is a severe one to the bereaved family upon whom it fell so suddenly.(11) Nothing more is known. Was it youthful exuberance that led a seventeen-year-old propelling a sulky down the main street of town at a speed fast enough to cause his death? We'll never know. "The post" that the sulky struck could have been the remains of a flagpole planted five years before, but its location in front of the Express saloon conflicts with the eyewitness who insists that Zany's flagpole was across the street from her husband's office. It could have been a hitching [post that Henry struck; it could have been the thick protective post at the corner, or it could have been the remains of the flagpole that flew the Union flag--the intersection of California and Third Street was often referred to as the "town square." Overbeck family lore recounts that Henry's death was caused by "running into a well in J'ville on Halloween."(5) While the date is definitely off, there were two wells at that intersection. Since the Overbeck family left Oregon long before the codification of the Ganung legend in the 1930s, their version of Henry's death is untainted by the legend-making machinery and should not be ignored. Perhaps the Overbecks are right, Henry pushed the sulky into a wellhead instead of a post, and it was the newspaper that got its facts confused. It wouldn't be the first time. The fate of the rebel flagpole is a tangle. It seems that if a flagpole had been raised one evening and survived less than one day in May before being chopped down, it should have been fairly easy to remove the stump from its hole--yet a photo in the SOHS archives does show a useless pole across the street from Zany's house in front of P. J. Ryan's store. That stump appears to be about two feet in height, probably too short (and, of course, in the wrong location) for the Overbeck story. Unpublished accounts of an unnamed "small boy's" death say that he fell from a wagon onto to the stump.(7) It's conceivable that a child could have met his death this way, but if so, the event is unrecorded (or at any rate, so far undiscovered) in the newspapers of the day. *Probably incorrect.  The Ganung house, December 31, 1965 Medford Mail Tribune. The newspaper has conflated the Petticoat War story with the rattlesnake flag story. 1. Paul Richardson, "Why Didn't We Celebrate?" Table Rock Sentinel, Vol 12, No. 1 (January/ February 1992), page 14. 2. Francis D. Haines, Jr., Jacksonville: Biography of a Gold Camp, Gandee Printing Center, Inc., Medford, Oregon 1967), pages 67-68. 3. Applegate Ranger District Notes on Historical Events (As Related by Ranger Lee Port), Medford, Oregon, February 6, 1945. 4. Southern Oregon Pioneer Association Records, Resolution on deaths of members, Vol. I, pages 114-116. Dated June 13, 1888 (error for September 13). 5. Unpublished notes of a July 1975 interview with Emma Bee Mundy (daughter of Amelia Elizabeth Overbeck, Henry's sister), Southern Oregon Historical Society vertical file. 6. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1884. 7. Interview with Carol Harbison, Southern Oregon Historical Society, February 1992. 8. Oregon Sentinel, May 19, 1861. 9. Oregon Sentinel, June 6, 1861. 10. 1860 Census of Jackson County, Oregon, Ruby Lacy and Lida Childers, 1990. 11. Oregon Sentinel, June 16, 1866. 12. Missing citation 13. "Death of Col. R. E. Maury," Medford Mail, February 23, 1906. 14. Mary L. Hanley, unpublished letter to Mrs. Robert C. Smith, August 28 ,1961. 15. "Death of Col. R. E. Maury," op cit. 16. Plat of Town of Jacksonville, G. Sherman, Surveyor, 1852. Notations on the copy in the possession of the Southern Oregon Historical Society. 18. Bert Webber, Historic Jacksonville: Alive and Well, Webb Research Group, 1990, map, pages 10-11. 19. Amy's Place occupied 120 East California Street. 20. Medford Mail Tribune, February 9, 1932, page 7 21. The Weekly Oregonian, Portland, Oregon, June 15, 1861, page 1. 22. "Thrills of Early Days Experienced by 'Father of Medford' Revealed," Medford Mail Tribune, undated, 1932. Howard's asserted that the flag "disappeared" seems as incredible as his estimation of the crowd at 800. He could be describing the flag's disappearance from the viewpoint of a person in the back of a crowd. He could possibly, in garbled syntax, be saying that the flag disappeared before the crowd arrived. 23. Oregon Argus, Oregon City, Oregon, June 1, 1861, page 1. Charley Williams is described as a "notorious gambler . . . who, in a fit of passion, killed another man at Dardanelles with a stool." (Fidler Scrapbook, Southern Oregon Historical Society, page 13) Williams is also credited with the first contribution to the building fund for the Jacksonville Methodist Church in 1853: " . . . Williams, in order to test the preacher's sense of duty, spoke up and said: 'All right, I'll lay a ten in the pot on this faro deal, and if it wins you take it all.' [Ad.] Helms then said: 'And if it loses, . . . . it shall be yours anyway.' It was a winter, Helms handed Royal [omission] and twenty. . . ." (W. M. Colvig, Forty-Fourth Annual Reunion, Oregon Pioneer Association, page 344) 24. Interview with Joe Wetterer, quoted in "History of Jackson County, Oregon," unpublished master's thesis of William Pierce Tucker, 1931, page 180. 25. Telephone interview with John Deuel, Ross family descendant, May 4, 1992. 26. Oregon Statesman, Salem, Oregon (advertisement), June 21-July 12, 1853. 27. Oregon Statesman, March 28, 1854, page 2 28. Ibid. 29. "The serious and bloody war that bad Indians and worse whites precipitated on the settlements of Rogue river valley this year [1855] did not retard permanently the material progress and prosperity of 'Jacksonville, nor did it diminish its population in any perceptible degree. Many of the single men, 'the boys,' in the old time vernacular, and many also who were heads of families, not caring for the causes of the conflict, shouldered their rifles in defense of their neighbors, abandoning profitable pursuits, many of them to catch Indian bullets, and by bravery and determination pushed the savages to unconditional peace. While they were in the field their places were filled by panic-stricken settlers, who flocked to the towns for safety, and whose presence was rather advantageous than otherwise. The community, especially the female portion, were in a state of continual dread, fearing a night attack by the Indians, but the volunteers were keeping the savages so busy in the field that no extra precaution against surprise was thought necessary. This apparent neglect aroused much comment among the women, and at last the excitement among them reached fever heat and forced them into a ridiculous position. A timid old man named Holman, with more imagination than courage, averred that he saw an Indian skulking through the brush at the outskirts of town, but among the men his story was generally discredited. Playing on the fears of the weaker sex, the old man induced them to call an indignation meeting in the methodist church, in order to arouse the men to the necessary of greater vigilance. A chairwoman and secretary were elected, but before the meeting proceeded to business, the men, to whom they looked for protection, were invited to step outside, and informed that the meeting was strictly a woman's one. Poor old Holman was hustled out with the rest, and this somewhat unkind treatment of the stronger sex was received by them with cheers and laughter and not taken seriously to heart. Meanwhile the ladies held a boisterous secret session. Resolutions denouncing apathy and lack of vigilance were passed, and the meeting adjourned with a general feeling that a well merited rebuke had been administered. That night some wags, lacking in due respect for the ladies, hoisted a petticoat at half-mast on the flag pole in front of the express office. The exposure of this piece of feminine apparel in so conspicuous a way was like flaunting a red flag in the face of a Spanish bull. It was not the red encasement of the famous scold, Zantippe, but a modest-looking garment, possibly intended as a flag of truce; but the act was misinterpreted as a declaration of war, and it was met with the spirit of incensed and outraged femininity. Knots of angry women gathered and discussed the situation, and two, whose ire knew no bounds, marched to the foot of the pole, armed with Allen "pepper boxes"--a fire-arm most dangerous to the holder--one with an ax, and fully determined to haul down the obnoxious garment. Men gathered round them, some in bad temper, and a word or blow might have created a bloody riot. One of the women demanded that the men haul down their colors, forgetting that a petticoat is an oriflamme that always arouses a man's chivalry. There was no response. Again the demand was made, and a vigorous blow from her ax made the pole quiver. At this juncture Dr. Brooks stepped forward and agreed to haul down the hateful bit of apparel, and the women marched off in triumph, firing their little guns in the air, totally regardless of the feelings of the poor men whom they had forced to an inglorious surrender. The end of the war was not reached, however, for the next morning an immense pine tree on the bank of Daisy Creek was adorned with a male and a female effigy, the latter in a gorgeous silk dress, and occupying a subordinate position in mid-air, taken to be indicative of man's superiority. This was a master stroke of aggressive strategy. There was no woman strong enough to chop the tree down, none bold enough to climb it, and no woodman could be found who dared bury his ax in the sacred trunk. The storms came, the winter winds whistled and moaned through the leaves of the pine, and still the effigies swung and swayed to and fro, as evidence that the weaker sex was fairly out-generaled."--A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, Portland, Oregon, 1884, pages 367-368. 30. Historic American Buildings Survey No. ORE-66, U.S. Department of the Interior, Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, page 38 -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

TOWN IMPROVEMENTS.--Already Sachs Bros. have torn away the old woolen fabric formerly occupied by Dr. Ganung from the lot purchased by them on California Street, next door to Love & Bilger's, and commenced excavation for the foundation of the large brick store they purpose to build. It will be twenty-five and a half feet front by seventy-five feet depth, put up in substantial, fireproof manner. The fine two-story frame building of McLaughlin & Klippel, on Third Street, is nearly completed, and is one of the most showy-looking houses in town. Small tenements and additions are being built in various quarters, and the place gives a daily evidence of enterprise and advancement. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, May 18, 1861, page 3 THE PALMETTO FLAG IN SOUTHERN OREGON.--A friend writes us: "I have just returned from Southern Oregon. While in Jacksonville I saw two flags raised--the glorious old Stars and Stripes, and the palmetto and rattlesnake flag. About the palmetto flagstaff there were a few staggering drunken men, who were hardly sensible of what they were about, and who were put up to do what they did by others who were in the shade; while the flagstaff of the Union was surrounded by a large crowd of intelligent and well-appearing citizens, and a goodly number of ladies. The ladies raised the flag, and as it spread to the breeze, there went up such a shout as never was before heard in Southern Oregon. Union is the strong prevailing sentiment here. There are but few Laneites who would glory in the downfall of this great Republic." Morning Oregonian, Portland, June 11, 1861, page 2 THE OREGONIAN "SOLD."--We see by the Oregonian of the 15th inst., that a traveling impostor had informed the editor of that paper that he saw, while in Jacksonville, a Union and also a palmetto flag raised. The only foundation for this is that on the 1st of May last the Germans of our town erected a maypole and placed on it an American flag. As regards the secession flagstaff, there never has, nor never will be, anything of the kind erected in this town. It is true, about six or seven weeks since, some of "the boys," with the idea of getting up a little excitement, one night hung up a pine tree rag on a rope stretched across the main street, which, at the break of day, was, without opposition, very properly torn down, and has not since been seen nor scarcely thought of. The opinion appears to be current in some of the northern counties of this state that a majority of the citizens of Jackson County are in favor of a recognition by the federal government of the Jeff. Davis Confederacy. We know this is not so. There may be a corporal's guard of disunionists in the county, who profess to believe that it will be "political suicide" for Oregon to continue her connection with what they term the "abolition government," but, thank God! this class of politicians is now "played out," and can never rally in sufficient numbers to do any harm. Though the people of Jackson have not been as demonstrative as those of some other sections, we have good reasons to believe that they are as patriotically attached to the Union and the ever-glorious Stars and Stripes. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, June 22, 1861, page 2

The Jacksonville Sentinel

says

that no palmetto flag has been raised in Jacksonville, and that there

is not a corporal's guard of disunionists in the county. Glad to hear

it.

Oregonian, Portland, June 26, 1861, page 2 LIBERTY POLE.--A new liberty pole is to be raised in a few days to take the place of the one on California Street, opposite the United States Hotel. We understand that a nice flag has been ordered from San Francisco, with which to ornament it. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, June 29, 1861, page 3 FLAG-STAFF.--A new flag-staff was raised during the week on the corner of California and Third street, and from it floats that beautiful banner, the emblem of our country's greatness. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, July 6, 1861, page 3 On motion of Mr. Davis, John S. Love was appointed and authorized to contract for and purchase of Mrs. Ganung a town lot in Jacksonville, and to pay three hundred dollars for said lot, and to draw the draft upon the Town Treasurer for that amount & report at the next meeting of the Board. July 23, 1861, Jacksonville Town Trustees' Minutes John S. Love, who was appointed to negotiate for the purchase of a lot of Mrs. Ganung, reported verbally that lot No. [omission] can be purchased for the sum of three hundred dollars, and he was continued that committee, with authority from the Board to conclude the purchase & procure a deed for the same. July 27, 1861, Jacksonville Town Trustees' Minutes INTERESTING DOCUMENT.

Some time since, there resided in this town one C. Lee, a blatant

secessionist, who, with others, endeavored to secretly organize a

company to join the Confederate army. These sweet-scented scoundrels

had a "chummy" who was a soldier at Fort Churchill and on the strength

of his acquaintance, and under pretense of loyalty, the crowd bummed

around the Fort, eating government rations, until the chummy was

drummed out of the service. This broke up the nest, and the last that

was heard of Lee, he was in the Boise country. Before leaving Gold

Hill, Lee deposited his pocketbook and papers with a citizen of this

place. That citizen, having retired from business, overhauled the

papers to sec if there was anything among them worth preserving,

when he came across the following interesting document, and handed it

to us as a literary curiosity. It is drawn up with great pains,

interlarded with ornamental chirography, German text, and all that sort

of thing, looking like a burlesque on the Declaration of Independence.

We publish it verbatim--giving

all possible publicity to the record of Messrs. M. Kelly, C. Lee and M.

George Cayce. The names of the other citizens of South Fork of Scotts

River, in Siskiyou County, do not appear. The document is not signed,

and is probably only a copy, preserved by Mr. C. Lee, the Secretary of

the meeting. Here it is:At a meeting held by the Citizens of South Fork of Scotts River in Siskiyou County for the purpose of organizing and passing secession resolutions, Mr. M. Kelly was called to the chair, Mr. C. Lee was elected secretary, when the following resolutions were read and unanimously adopted, and Mr. M. George Cayce was called upon to address the meeting, which he did in an able and efficient manner. WHEREAS the policy adopted by President Lincoln and his confederates, is subservient (subversive?) to all laws of justice both humane and divine, and that while he and his associates had it in their power to effect a peaceable solution of our difficulties and restore peace and happiness to our distracted country, by acknowledging the independence of the confederate States he has WILLFULLY by adhering to the black Republican heresy, signed the death warrant of our free institutions, and involved our country in a civil war. Resolved That we, this fourth day of May A.D. 1861, raise the flag of the Southern confederacy, and UNANIMOUSLY SWEAR ALLEGIANCE and PROTECTION to the same. Resolved That we claim no protection from the so-called national government, but look upon the Southern confederacy as the only one under which we can exist as a free and independent people. Resolved That we the citizens of South Fork here assembled, tender to our Southern brethren, OUR LIVES, OUR FORTUNES and OUR SACRED HONOR in sustaining their constitutional rights. Gold Hill Daily News, Gold Hill, Nevada, March 3, 1865, page 2 ACCIDENT.--The Sentinel says that on Wednesday evening of last week, as Henry E., the only son of Dr. A. B. Overbeck, of Jacksonville, was pushing his father's sulky before him, on California Street, he accidentally ran it against the post at the Express Saloon corner, and so great was the rebound that one of the shafts struck him in the side and inflicted injuries from which he died on the subsequent evening. Oregon State Journal, Eugene, Oregon, June 23, 1866, page 3 DR. GANUNG, of Jacksonville, has been appointed Post Surgeon at Fort Klamath. Oregon State Journal, Eugene, Oregon, December 8, 1866, page 2 This may not have been correct. Rented Fowler house to Mrs. Ganung at $8-- per month, commenced Jany. 20/67. Pd. $8 Feby. 21st 1867. Beekman Papers box 1, vol. 25, Oregon Historical Society Research Library Coroner--L. Ganung. "Republican County Nominations," Oregon State Journal, Eugene, May 21, 1870, page 3 From the Jacksonville Times: On the 30th December, Coroner Ganung held an inquest on the body of a newly born infant found in a shallow pool of water a short distance from Maegerle's house on Evans Creek. From the evidence adduced, it appears that the mother of the child is a young woman, who attended the Christmas ball at Rock Point and danced all night and was stopping to rest at Mr. Maegerle's on her way home. The whole case presents most revolting features. "State News: Jackson County," Weekly Oregon Statesman, Salem, January 18, 1871, page 3 DISASTROUS FIRE AT JACKSONVILLE.--On Thursday evening of last week Jacksonville was visited by the most disastrous fire ever known to that place. It originated in the United States Hotel and rapidly spread, consuming a vast amount of property. The following are the losers, as given by the papers of that place: P. J. Ryan, store, $30,000; Louis Horne, hotel, $10,000; Kubli & Wilson, stable, $4,000; Mrs. Brentano, millinery store, $700; Dr. Aiken, books and instruments, $400; Hull & Nickell, Times office, $1,500; Cronemiller & Co., blacksmith shop, $2,000; James T. Glenn, dwelling house, occupied by Mrs. T'Vault, $1,000; Jacob Meyer, wheelwright, $1,000; Pat. Donegan, blacksmith shop, $1,000; Dr. Danforth, office appurtenances, about $150; Mrs. Ganung, dwelling house, etc., $1,000; James Casey, bowling alley building, $1,000; the Misses Kent lost their household goods, etc.; M. Caton saved most of his tools, as also did Cronemiller & Co., Jacob Meyer, Pat. Donegan and others, some of theirs; John Miller, John Noland, Mrs. T'Vault, Mrs. Kinney, W. Million and several others also lose considerable. Much loss was also sustained by moving goods from houses uninjured by fire. Oregon State Journal, Eugene, April 12, 1873, page 2 Mrs. Ganung's new dwelling house is being pushed forward rapidly to completion. "Local Gossip," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, April 26, 1873, page 3 A couple of good rooms can be rented at Aunty Ganung's. "Local Items," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, December 1, 1880, page 3 Some miscreant carried off a piece of the tombstone that stands at the head of the grave of the late Dr. Ganung in the Red Men's cemetery, which makes the balance utterly worthless. Such conduct cannot be too severely condemned. "Brief Reference," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, March 11, 1881, page 3 Aunty Ganung, we regret to say, has been quite an invalid of late on account of neuralgia in her face. "Local Items," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, June 11, 1881, page 3 Of the committee of ladies who managed the women's condolence meeting, and to whom, with Mrs. Dowell's aid as presiding officer, its success was attributable, are Mrs. J. McCully, Mrs. W. J. Plymale, Mrs. E. Kinney, Miss A. Ross, Mrs. Kubli, Auntie Ganung (a venerable lady in gray hair and snowy cap border whose years and grace rendered her conspicuous among the younger occupants of the platform) . . . Abigail Scott Duniway, "Southern Oregon," New Northwest, Portland, October 6, 1881, page 1 Mrs. Zany Ganung was born in Madison County, Ohio, February 15, 1818, and emigrated from Illinois to Oregon in 1847. "Southern Oregon Pioneers," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, July 15, 1882, page 3 Mysterious Disappearance.

Three weeks ago last Tuesday evening Dr. C. Lempert left this place and

has not since been seen or heard of by his friends here. On leaving his

boarding house, he notified his landlady, Aunty Ganung, as was his

custom, that he was going on Applegate to see a sick man. He was heard

conversing with someone, presumably the man who came for him, and the

two took their departure together at about eight o'clock in the

evening. He has not returned, and no news has reached town concerning

him. The authorities should take steps to ascertain his whereabouts. In

the meantime the man who accompanied him away will confer a favor on

his friends by telling what he knows about him. Should any of our

readers on Applegate or anywhere else know anything about the Dr., we

shall be pleased to hear from them.--Jacksonville Sentinel.

Lebanon Express, Lebanon, Oregon, October 7, 1887, page 3 John Ross and Elisebeth Hopwood were the first white couple to be married in Jacksonville, and the second in the county, Mrs. Cantrall recalls. . . . John and Elisebeth's daughter, Mary Louisa Ross, was the first white girl born in the city of Jacksonville. Her birthday is given as October 8, 1853, her death as May 31, 1913. Her brothers and sisters were Jane Elisebeth, Abarilla, Lewis Ganung, Adelaide, George Brown, Thomas Drew, Margaret, Minnie and John Edgar, the youngest, who was born in 1872. "Native Daughter Recalls Early Jackson County Day," October 13, 1957 Medford Mail Tribune, page B7 Plans for a delicatessen with sidewalk cafe, and for a gift shop in downtown Jacksonville, were announced today by Stuart Hinson, Circle G Ranch, Little Applegate. Hinson recently purchased buildings at 170 and 160 W. California St., as well as what is known as the Coleman Hardware Store building across the street at 125 W. California St. He said that he has razed the small white building at 160 W. California St., and that he plans to build here a brick structure to house a gift shop that will be operated by his wife. "Cafe, Gift Shop Set for Downtown Jacksonville," Medford Mail Tribune, March 4, 1969, page 9  Last revised September 12, 2022 |

|