|

|

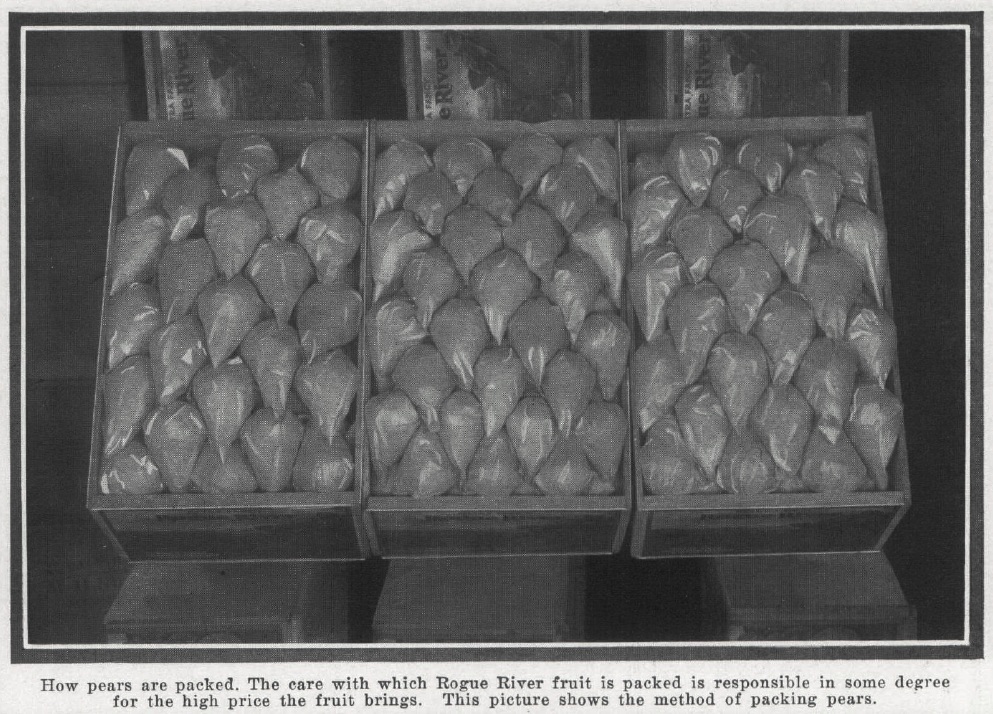

Fruit Packing It wasn't so much the fruit that

made

the Rogue Valley famous, it was the packing.

Also see the page on orchard history. For a page abou pack trains, see the Freighting page.  From a 1909 Medford booster booklet. APPLES.--Our market is abundantly supplied with fall apples, which are selling slowly at from 5 to 7 cts. per pound. Most of them reach us in bad condition, and we would suggest to our Willamette friends that in the future, if they would prepare their fruit in the same manner as they would for San Francisco, they would receive ample remuneration for their extra labor and expenditure. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, October 19, 1861, page 3

. . . one of our leading commission merchants

recently made a fruitless trip as far as Rogue River Valley in search

of fruit. Though he found plenty of men who expected to have fruit to

sell this fall, he was unable to convince them that it must come to

market in an attractive form. They could not see why they should be

required to buy new boxes, when they could get all the old barrels and

soap boxes they wanted for nothing, not even when they were informed

that to do so would add more to the value of the fruit than the cost of

the boxes.

West Shore, Portland, May 1884, page 125 First Shipment of Oregon Pears

Over the Northern Pacific. Portland News.

The

Bartlett and other varieties of pears raised in California find a ready

sale in the eastern markets. Several companies are engaged in packing

and shipping them, and they find the business profitable. The method

adopted is to wrap the fruit in tissue paper as soon as it is taken

from the trees. To do this properly and quickly requires considerable

practice. The pears are then placed in twenty-five-pound boxes which

are provided with holes to freely admit the air and then put aboard of

the cars. These cars are attached to the express trains and hurried to

their eastern destinations as fast as possible. The packers usually buy

the fruit on the tree in the orchard and pluck it before it is ripe in

order that it may not spoil while en route. The shippers can afford to

pay a high price per carload, and still realize a handsome profit.

Oregon raises Bartlett pears, the like of which cannot be found

elsewhere. With the opening of the Northern Pacific Railroad there

comes a chance to dispose of the surplus fruit to the people of the

East. It is an opportunity which should be immediately taken advantage

of. One commission merchant, F. H. Page, has had the foresight to see

the possibilities in this direction, and yesterday he sent the first

lot of 100 boxes of Oregon-raised Bartlett pears to the East via the

Northern Pacific Railroad. By so doing he has made himself the pioneer

in a business which is destined to be one of great importance to the

people of this section.

WE KNOW HOW TO PACK APPLES.Ashland Tidings, August 15, 1884, page 1 Oregon Fruits Going East.

Eastern

buyers and dealers in fruit find that the demand for Oregon fruit has

increased amazingly. The leading commission houses of Portland have

been filling orders by the carload right along during the entire

season. F. H. Page on Saturday sent a carload, another leaves this

morning, a third tomorrow, and orders for like quantities still remain

to be filled. At present the White Doyenne pear is claimed to be the

favorite. Each pear is wrapped in soft paper and laid carefully in the

box in layers. The boxes when filled are put in a device that clamps

the ends of the lid, when a slat is laid on top and then the top, and

all are solidly nailed. Each box contains forty pounds, and 500 boxes

make a carload. These shipments are going direct to St. Paul and

Chicago. It takes the fruit about six days to go to the former and

eight days to the latter place. Mr. Page's packing rooms is a beehive

of industry and presents an interesting and instructive sight to the

visitor.--[Portland

News, August 31.

Ashland Tidings, September 11, 1885, page 1 "Another drawback to the green fruit business is that, with but few exceptions, it is impossible to get a carload of any particular kind of fruit in one orchard. The fruit producer should confine his product to a few choice varieties in order to make the business a paying one." Fruit dealer H. E. Battin, "Fruit Trade in Oregon," Ashland Tidings, January 8, 1886, page 1 Packing Apples.

Rogue River Courier,

Grants Pass, October 22, 1886, page 4

"Handle apples as you would handle eggs" is good advice. Old flour

barrels, unless carefully washed and dried, will impart a musty flavor

to the fruit before midwinter, especially if the air in the cellar is

moist. The first apples which are put in market barrels should be

"faced." The facing consists in placing two or three layers on the

lower head with stems down; that is, with stems pointing toward the

head. Clean, bright apples of ordinary size should be selected for this

purpose. The rest of the apples may be poured into the barrel. This

pouring, if properly done, will not injure the apples. Eggs can be

poured. Use a basket with a swinging handle, one which can be lowered

into the barrel and turned while there, and hold the apples with the

hand so that they will not pour out too rapidly. Two or three times

during the filling shake the barrel gently to settle the apples firmly.

Face the upper head in the same manner as the lower one. It is

desirable not to head up the barrel at once. Cover with boards to keep

out the rain, and let the barrels stand open four or five days. It is

not, however, always possible to cover the barrels, in which case they

maybe headed up at once and turned down on their sides. In this

condition they will shed water.--[American

Agriculturist.

The picking season had already begun at the time of our visit, and in the orchards were heaps of apples and pears waiting to be packed for shipment. In some of the gardens we found wonderfully high berry bushes laden with fruit. Contrasted with some other Western scenes, the country about Ashland seemed delightfully tame and natural and subdued. There was exquisite blending of colors, and the orchards, with their long rows of trees and apple heaps, made a lovely picture. Edwards Roberts, "A Western Summer," The Evening Post, New York City, July 19, 1887, page 3 Fruit Boxes.

We

are prepared to furnish any quantity of extra fine fruit boxes, of any

style or weight desired, at prices that defy competition. Our boxes are

all made of thoroughly seasoned sugar and yellow pine; they are

brighter, lighter and stronger than any other box made on the northwest

coast. Box ends stamped with desired brands. With our extensive box

factory, just erected at Merlin, we are prepared to fill large orders

on short notice. Prices, laid down at all points, furnished on

application.

SUGAR PINE DOOR & LUMBER CO. Grants Pass, Or. Ashland Tidings, July 27, 1888, page 3 During the past season immense quantities of apples were sold on the ground to California companies, who sent experienced packers into the orchards, packed the fruit and labeled the boxes "Mountain fruit, grown in the foothills of California." "The Rogue River Valley," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, April 18, 1889, page 1 Fruit Boxes.

Before buying boxes get prices from the Sugar Pine Door &

Lumber

Co. at Grants Pass. They will sell peach boxes at 4½ cents,

and

all other boxes in proportion.Ashland Tidings, July 31, 1891, page 3 Advertising Oregon.

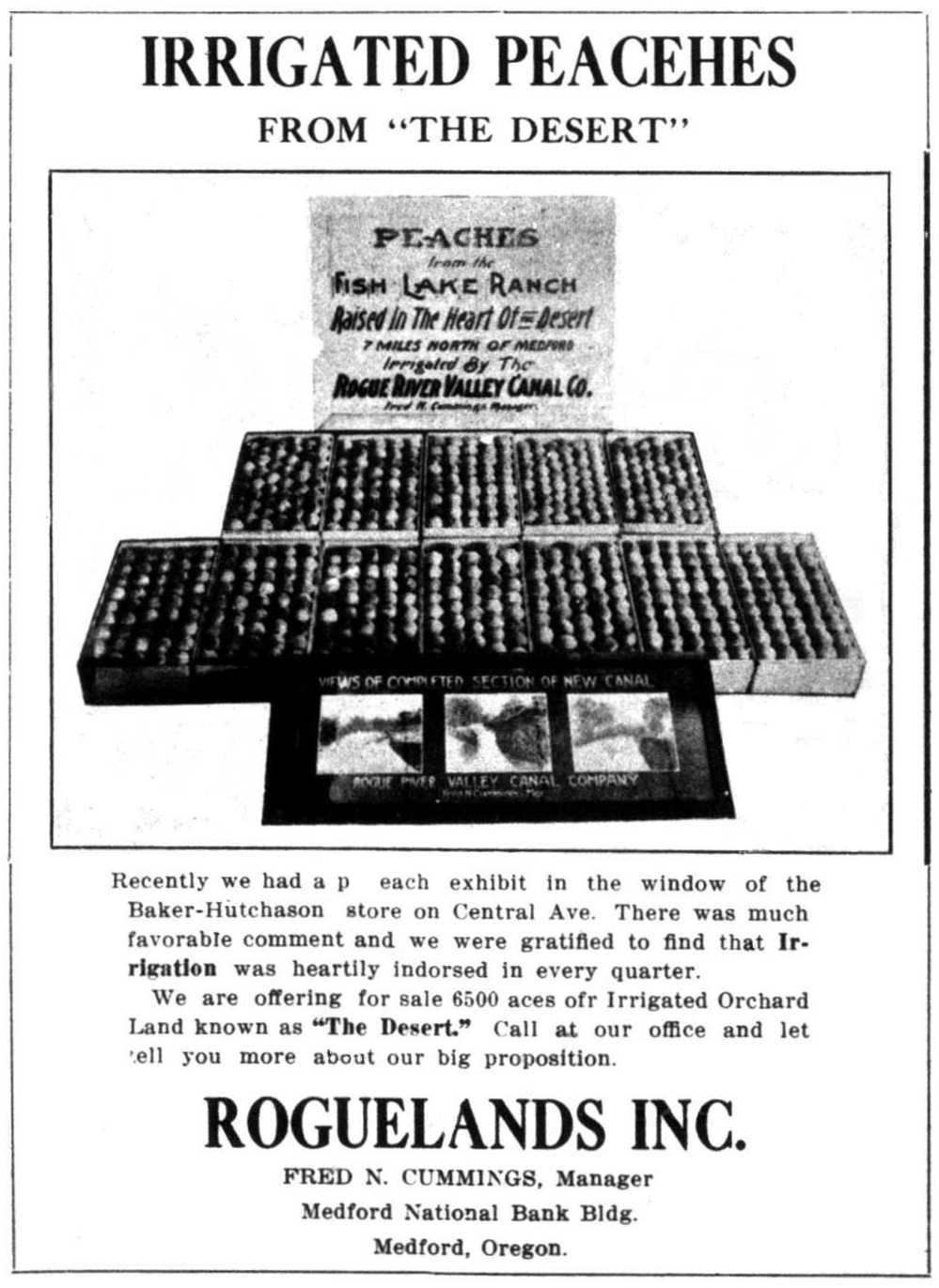

People who are fortunate enough to obtain peaches from the "Peachblow

Paradise Orchards" of Max Pracht this year will be fully apprised of

the celestial character of the fruit, no matter in how distant a clime

it may be unpacked and eaten. Mr. Pracht has just had nearly 100,000

peach wrappers printed, each bearing in blue ink on white paper his

orchard trademark designed by himself. It advertises the climate of

southern Oregon, the city of Ashland, the orchard business of Mr.

Pracht, and there will be no danger of retail dealers in Oregon,

Washington, Montana or elsewhere selling his peaches as "California

fruit." Neither will there be any likelihood of any scrubby peaches

being shipped in those wrappers. Mr. Pracht's method of paying the

strictest attention to the details of selection, packing and marketing,

proves its value from the fact that he is able to ask and receive for

his peaches 25 percent above the market price. The farmers of the state

should have their attention called to this fact, and much good to

Oregon would undoubtedly result if his example were to be generally

followed. One of the most striking instances of the injustice he seeks

to correct by advertising is the fact that Rogue River apples,

pronounced by connoisseurs the finest by long odds on the coast, are

shipped to eastern markets branded "California fruit," says the Oregonian.

Democratic Times, Jacksonville, August 18, 1893, page 3 A Fruit Farm that Pays.

The

fruit farm of J. H. Stewart, situated halfway between Phoenix and

Medford, about ten miles north of Ashland, presents an attractive scene

of busy industry this week. The great Bartlett pear orchard of 60 acres

planted by Mr. Stewart six or eight years ago is beginning to yield its

generous returns for the intelligent and vigilant labor and care

expended upon it, and the first crop of consequence is now being picked

and shipped.

Page & Son, of Portland, have bought the entire crop at 1½ per pound. Mr. Stewart picks the pears and delivers them in boxes to Page & Son at the packing house on the farm. Here they are wrapped and boxed by Page's people, after which Mr. Stewart delivers them to the cars. Twenty-seven women and girls are employed packing the fruit, and about as many men are at work picking, boxing and hauling; so the farm, as remarked at first, is a busy camp at present. The crop is picked and shipped at the rate of a carload a day, and will make from twelve to fifteen carloads bringing Mr. Stewart about $4,000. The girls are paid by Page & Son 4 cents per box for wrapping and packing the pears. They are camped in tents on the farm. The orchard is an object lesson to people interested in fruit growing in Southern Oregon. The trees are free from the scale, and the fruit is free from the grub of the codling moth. Capt. Teel and R. S. Barclay, of Ashland, visited the orchard last Monday, and George W. Crowson, of this place, and Mr. Sheffield of Portland were there Tuesday. They advise everyone who may be inclined to grow discouraged over the fruit business, on account of the orchard pests that have appeared within the past few years, to go and see the clean trees and fruit of Stewart's orchard. It shows that an orchard may be kept free of the San Jose scale, and that apples and pears may be saved from damage of the codling moth. The Tidings will have more information in a future issue concerning Mr. Stewart's successful orchard management. Ashland Tidings, September 1, 1893, page 3 Nearly thirty females have been employed at Hon. J. H. Stewart's farm near Phoenix the past few weeks, in wrapping and packing Bartlett pears for the eastern and northwestern markets. The product of the entire orchard of sixty acres has been purchased by F. H. Page & Son at 1½ cents per pound and is of the finest quality. As about fifteen carloads will be shipped, Mr. Stewart will receive about $4000 gross for his pears. He is one of the most prominent, painstaking and intelligent horticulturists on the coast, and well merits his success "Here and There," Democratic Times, September 8, 1893, page 3 F. H. Page, of the firm of Page & Sons, Portland, was a visitor in Medford yesterday, after having spent several weeks' vacation on the fishing grounds of the Klamath country. Mr. Page has the distinction of being the first [fruit] shipper from the Rogue River Valley [H. E. Battin & Co. preceded Page & Sons.], and his reminiscences of old times are replete with interest. The first car of pears came from the old Stewart orchard, now the famous Burrell property. This was in 1889 or 1890, Mr. Page is not certain which. [Fruit was shipped by the carload from the Rogue Valley in 1884, the year the railroad arrived.] In order to make the pack worthy of the quality of the fruit, which was destined to astonish the New York and other markets and create a standard which has never been equaled by any other fruit section, Mr. Page brought a force of ten or twelve people from Portland to sort and pack the pears, wrap and box them in fancy style, and personally supervised the work. The result was so satisfactory that the banner price of 80 cents per box gross was paid to the grower. Nothing but the very best fruit was packed, Mr. Page stating that thousands of boxes of pears and apples were annually thrown away, and yet worthy of being considered first-class stuff in the desire to confine strictly to fancy grades. "Early Days of Fruit Shipping," Medford Mail Tribune, July 27, 1910, page 4 The remainder of the article is transcribed here. Southern Oregon Pears Are All

Right

From the

Rural Northwest.

The statement recently appeared in one of the leading newspapers of this state that Oregon-grown Bartlett pears do not stand shipment well unless packed before they are fully grown. Although this statement was made by a gentleman who ought to know what he is talking about, the Rural Northwest is not inclined to accept it as a fact. A great many of the pears which were grown in Oregon this year would not stand shipment well for the simple reason that the trees had not been properly sprayed with the Bordeaux mixture and in consequence the fruit was attacked by fungus and made ready to rot on the slightest provocation. No such fruit should ever be shipped out of the state. On the other hand, the Medford Mail reports that returns have been received from the several carloads of pears shipped from that place and that in every instance they were reported to have reached their destination in splendid shape. Messrs. Stewart and Weeks & Orr, the orchardists who raised these pears, have the reputation of caring for their trees in the most thorough manner, and they did not have to pick their pears before they were grown to make them keep, even when they were shipped to New York. Medford Mail, October 27, 1893, page 1 Medford Apples at Chicago.

Below is a letter received by Mr. J. H. Stewart from

the World's Fair superintendent of horticulture for Oregon:

J. H. Stewart, Medford, Oregon. Dear Sir:--We received the shipment of fruit from you on the 10th inst. and found it in prime condition--in fact it was packed perfectly and could come in none other than good shape. Your variety was very good, and size, quality and color cannot be equaled anywhere. The judges of the department say, and do not hesitate to say, your Jonathan, Hoover, Baldwin, Monmouth and others were the finest they have ever seen. In this instance it is a matter of sixty or seventy years experience in fruit, and it is a feather in the cap of apple culture in Oregon to be the subject of such favorable comment. We are far in advance of all competitors in all fruits, and it is through the efforts and enterprise of our growers that enables me to make this statement. I wish to thank you and the people of Oregon for their kind endeavors to assist me here. With great consideration, I am yours truly, JAY

GUY LEWIS.

Medford Mail,

October 27, 1893, page 2

C. W. Skeel ad, August 11, 1893 Medford Mail The ninth annual meeting of the state horticultural society was called to order Tuesday morning of this week by president Cardwell at the A.O.U.W. temple in Portland. . . . Max Pracht, of Ashland whose peaches "beat the world" at the world's fair, read an interesting and practical paper on the subject of "Horticulture for Profit; or, Fancy Fruit, Fancy Packages, Fancy Prices," showing from his experience the advantage it was to the fruit growers to establish a reputation by sorting his fruit, being honest with the commission merchants with whom he deals and then making elaborate use of printer's ink. By packing choice fruit in fancy boxes a fancy price could be commanded. Such boxes were expensive but the appearance of fruit wrapped in white paper and packed in them, ornamented with blue labels, were such a temptation to housekeepers that they could not resist purchasing them. "State Horticulturists," Corvallis Gazette, January 12, 1894, page 1 A great many apples of inferior quality are being shipped to eastern points from this valley, which is likely to result in much injury to our reputation as a fruit-growing section, as some of them are likely to be represented as of standard grade. Nothing but a first-class article of fruit should be shipped from southern Oregon. "Local Notes," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, January 29, 1894, page 3 DEPENDS

ON THE PACKING.

G. W. Barnett, of

Chicago, president of the international league of commission merchants,

says that the future of the fruit industry in this country [i.e., in Jackson County]

is in the hands of the packers. "You have the fruits, and it only

depends upon your own actions as to how great your profits shall be."

We should put nothing in our boxes that we would be ashamed of in St.

Paul and Chicago. Mr. Barnett called attention to the fact that we

should learn by the experience of others as well as of ourselves; it is

the fool who learns nothing except by his own experience."Farmer's Column," Medford Mail, March 9, 1894, page 4 At the fruit house apples with a mere speck on each can be bought for twenty cents per bushel. Reese P. Kendall, "He Writes of Medford and Her People," Medford Mail, March 30, 1894, page 1 Messrs. Weeks & Orr are among our most prominent orchardists, and in these gentlemen are recognized such growers as not only grow and pack fruit in such manner as will profit themselves but their products and work being such that will redound to the good of the entire valley. They have had returns from four carloads of Bartlett pears sent to Chicago, and these returns are very flattering. "They were in excellent shape, well packed and the fruit a good seller"--is the language used. Mr. Orr states that they take special care in packing and have had the same packers employed for eight years. "News of the City," Medford Mail, September 27, 1895, page 5 SUCCESSFUL FRUIT GROWER.

High Prices Paid in New York for Fruit Shipped by J. H. Stewart.

The Fruit Trade

Journal, published

in New York, has the following to say of fruit shipped from Medford,

Oregon, by Mr. J. H. Stewart, the former well-known fruit grower of

Quincy:

Mr. J. H. Stewart, of Rogue River, furnished a car of Beurre Clairgeau pears and astonished New Yorkers when sold. Lately he furnished Page & Son a car of Winter Nelis pears that were sold in New York for fabulous prices, because they were large and very fine. He had cultivated and packed them so that they reached New York in the best shape; discarded all small or inferior fruit, and sent only the best. The result was that they sold for double the price a car brought that were average pears, and not packed well. That car was very heavy, much heavier loaded than the average, selling for over $2,000. They paid for size, cleanliness and excellence. J. H. Stewart sprays his trees, and his pears and apples have no insects, no fungus, no blight; are extra large and extra fine. Such fruit goes on the tables of the "nobs," and they pay extra to have the best. The man who can command that trade will make money where merely ordinary fruit will hardly pay at all. Excellence will always pay in fruit growing. The Quincy Morning Whig, Illinois, February 5, 1896, page 3 The Fruit Industry.

This

is the time of year when orchardists who desire a good, merchantable

quality of fruit, should carefully prune and spray their orchards. It

is a notable fact that more small, worthless fruit is grown on account

of lack of proper and sufficient pruning than from any other one cause.

Fruit pests are bad, of course, and trees must be protected against

them to bear good fruit, but no tree can bear large and fine fruit,

although it be perfectly protected from pests, with four times as many

fruit-bearing branches as it ought to have.

Those who are careful and painstaking with their orchards are constantly disparaged in the markets by those who are not. It is certainly the duty of shippers of fruit from the county to protect, as far as possible, the clean and worthy fruit raiser from the unclean and careless, by refusing to handle fruit of a small and inferior quality. The reputation of the county, as a super fruitgrowing section, cannot be maintained unless the standard is carefully kept up, and shipments closely guarded as to quality. It should not be forgotten that if intelligently prosecuted the culture of fruit is destined to be one of the important industries of the county. With proper care a large annual revenue may be confidently depended upon from this source. Experience and results will soon teach those who handle and deal in this product that it must be carefully picked and properly packed when intended for market. There is much room for improvement in the line of drying, evaporating and tastefully preparing this character of the product for market. Much depends on appearance. A case of fruit nicely put up and tastily exhibited will sell, when one of equal quality, but less attractive, will go begging for a buyer. Medford Mail, March 2, 1900, page 2 F. V. Martin, formerly with the Earl Fruit Co., of Portland, was in town the forepart of the week looking into the prospective future of the fruit of this section. He has been in Southern Oregon and reports everything O.K. in that locality and the outlook favorable for a large yield of fruit. But since his departure there has been heavy frosts, and the prospects may not be so flattering as they were. Mr. Martin is now in business for himself in connection with others and has arranged to buy, or rather, has partially purchased quite a quantity of fruit at a given price in the orchards. Mr. Martin in such deals generally paid $1 down, the balance to be paid when the fruit is accepted. It is stated that he negotiated for a crop of Bartlett pears in Southern Oregon, agreeing to pay one cent per pound for the crop picked and piled in the orchard, Mr. Martin to pack the fruit for shipment at his own expense. "Local News," Union Gazette, Corvallis, April 13, 1900, page 3 Oregon Red Apples Go Everywhere.

Hon.

J. H. Stewart has done much to establish a reputation for Oregon fruit

in almost all countries of the known world. His fruit has in years

agone been eaten in London, Liverpool, Calcutta, Hong Kong, Glasgow,

Paris, and we truthfully say, we think, in every important city in the

United States and Canada. He has established this reputation by growing

only the very choicest fruits and in packing them in the most careful

and painstaking manner. For years Mr. Stewart has packed and shipped,

each season, several hundred boxes of both pears and apples for J. J.

Valentine, president of the Wells, Fargo Express Company, these

addressed to officials of the company and to his friends in all parts

of the United States and Canada. This year Mr. Valentine's order is for

170 boxes of Winter Nelis pears and over a thousand boxes of apples.

An order is now here for the pear and part of the apple shipments.

These boxes will all be labeled and shipped, with few exceptions, one

box to an individual and go to nearly as many different cities as there

are boxes sent. An idea of the range of shipments can be gotten when we

give a list of a few of the cities to which they go, namely: Chicago;

Portland, Oregon; Portland, Me.; New York City; Galveston, Texas; St.

Paul, Minn.; New Haven, Conn.; Montreal, Canada; Englewood, N.J.;

Boston, Mass.; Washington, D.C., and hundreds of other eastern cities.

Several years ago Mr. Valentine sent to his eastern friends boxes of

California nuts, but the growers, after a time, began gouging him on

prices and flim-flamming in quality, and he switched to Oregon fruits

and for a number of years has paid his compliments in Southern Oregon

products. Mr. Stewart charges Mr. Valentine no more than the fruit will

bring elsewhere in the market, and in all his shipments no inferior or

disease-infected fruit has been packed. Nothing could more

substantially advertise Oregon than the sending of this fruit broadcast

throughout the East, and to Mr. Stewart belongs the credit for having

made it possible for us to so advertise.

Medford Mail, October 19, 1900, page 3  Weeks and Orr packing house 1895, March 23, 1989 Medford Mail Tribune "City Happenings," Medford Mail, November 23, 1900, page 7  There are sixteen girls employed at Olwell Bros.' packing house. They will not be able to finish the apple crop for a month. "Central Point Items," Medford Mail, November 30, 1900, page 3 J. A. Whitman loaded and shipped two carloads of fancy apples last week, direct from Medford to Liverpool, England. They were Yellow Newtowns and were an especially selected lot--dainty and choice morsels, as it were, for England's nobility. While in years agone much of the fruit of Southern Oregon has found market in foreign cities, it has not been a common occurrence for it to be shipped direct from place of lading. It is usually put through from one to three eastern commission houses before it reaches its place of consumption. "City Happenings," Medford Mail, November 30, 1900, page 7 The orchard comprises 160 acres, all in apples but 1500 trees of Winter Nelis pears. Every apple shipped from the Olwell orchard sold in London or important eastern markets comes out of the original box wrapped in paper. The box is sugar pine, marked in large letters "Oregon Apples," together with the additional private stamp of the orchardists. The bottom and sides are lined with paper. Between each layer is paper, blue in color and of cardboard variety. On top is a paper of the same kind, and the lid is sprung in place with a machine and nailed. The apples in the box are packed with such exactness that when the lid is finally nailed on there is no shifting of position by the fruit inside. For packing purposes, the apples are classified into four-tier and five-tier grades, according to size. Four-tier apples are those in which four apples exactly make a row in a tier and in which four tiers fill a box. The five-tier size takes its name for similar reasons. No apple is packed that is not absolutely perfect. The color must be right, the shape proper, and there must be no flaw or blemish that the eye can see. In the picking, 50 men are employed. During the packing season 20 girls are kept constantly busied at their duties. The packing is done in huge fruit houses, fitted with convenient tables and appliances for systematic prosecution of the work. Packing of apples for a carload does not begin until the fruit has been contracted. A telegram is received in the morning while the apples are still in bulk. At evening time the car of newly packed apples stands on the siding, to be taken way by a train within an hour or two after the process is completed. "Oregon Apples Bring Top Price," Medford Mail, January 18, 1901, page 2 Stealing Oregon Honors.

From

the Eugene Register.

A great injustice is being practiced upon our orchardists and other fruit growers year after year by Oregon cannerymen and fruit jobbers. Our fine fruits, after being canned and packed, are labeled "Choice California Fruits," and sent to the markets as products from that state. We understand that Lane County's excellent crop of Royal Anne cherries now being canned by the carload and prepared for shipment at the Eugene Cannery and Packing Company's factory are to be labeled in this manner. California is noted for her grafting tendencies in the matter of exploiting the best products of other states on the public as her own, and it is small wonder that her reputation as a fruit-producing state is widespread. The cannerymen reply in defense of their action that it is doing the fruit men a kindness in labeling their product "California fruits," claiming that it causes a very ready sale on account of California's great reputation as a fruit producer. While this may be true in a measure, how soon would Oregon attain distinction as a producer of fine fruits if the annual yield of her orchards is credited to some other state? The sooner this practice is discouraged the better it will be for Oregon fruit raisers. We should feel justly proud to stand on our own merit as a fruit-producing state. Medford Mail, July 26, 1901, page 2 OUR APPLES IN GERMANY.

GRANTS

PASS, Feb. 26.--(To the

Editor.)--I have seen a letter from W. N. White, wholesale fruit

dealer, of 10 Jay Street, New York, published in The Oregonian

two weeks ago, wherein Mr. White, by implication, reflects on the

integrity of Weeks & Orr and J. A. Whitman, apple-growers and

packers, of Medford, Or., because the German authorities at Hamburg

rejected 600 boxes of apples alleged to have been grown by Weeks

&

Orr, and one lot bearing the brand of J. A. Whitman.Reply to the Statement as to Infection with San Jose Scale. Mr. White, in his letter, assumes because the Germans rejected, and assigned as a reason that the apples were infected with San Jose scale, that it must have been true. In the case of the 600 boxes bearing the brand of Weeks & Orr, I know that it was not true that any of these apples were infested with scale, and the rejection was for other reasons than scale. The Germans have but little knowledge of the San Jose scale, or if their knowledge is such that they could identify the scale their rejection and assigning that as a reason was a mere pretext. On November 28, 1901, I received a letter from Olwell Bros., of Central Point, stating that they had bought a car of apples from Weeks & Orr, and that they intended shipping them to Hamburg. They wanted me to make an inspection of the same, as they had been informed that the Germans were very strict in regard to San Jose scale, and as they were putting up a fancy pack to enter that market for the first time they were anxious to meet all quarantine regulations of Germany. I wrote Olwell Bros. that I would be at their place on December 3, and for them to have the apples carefully assorted, rejecting any apple that had the least suspicion of being infested with scale, and to have the apples intended for the German market in their assorting boxes, so that I could make a thorough inspection before wrapping and packing. On December 3 I made a most careful inspection of this lot of apples, using a strong glass, as I was determined if I found a single scale in the lot not to issue a certificate. I found the apples free of scale, as well as the worm, and issued my certificate to that effect. At that time I advised Olwell Bros. to attach the certificate of inspection to their shipping bill, which they did. As a precaution to prevent the possibility of a single infested apple being packed I tested the knowledge of the girls who did the packing as to scale, and found them experts as to its identification. I instructed each of them, as well as the foreman of the packing-room, that any apple that created a suspicion of scale in their minds to reject it. J. A Whitman, of Medford, is one of the largest packers and shippers of apples in the third district. He has been engaged in the business the past 11 years. On November 5, 1901, I made a careful inspection of his packing-house at Medford. By referring to my notes on that inspection, I find the following remarks, to wit: "Inspected several hundred boxes of apples, and found them free of scale. This packer is exercising great care in shipping clean fruit." In the case of Weeks & Orr, I personally know there was no scale in the 600 boxes. From what I know of Mr. Whitman's careful methods in packing, I cannot believe apples offered under his brand were honestly rejected by the Germans because of San Jose scale, but that scale was made the pretext. In the past we know Germany has discriminated against American meats, without any just cause. For trade reasons might not Germany use any pretext she thought best to keep our fine red apples out of her markets? A.

H. CARSON,

Morning

Oregonian, Portland, March 1, 1902, page 11Horticultural Commissioner, Third District. Careless packing of fruit is a suicidal policy. It not only hurts the individual shipper, but reverts with the force of a boomerang upon the whole community. If the practice is continued it will drive buyers away; and then the fruit men will be at the mercy of the middlemen. Most fruitgrowers in Oregon know what that means. The orchardists of the valley have made themselves independent by their own enterprise, and cannot afford to sacrifice that independence through the carelessness of a few people in not properly packing their fruit. In some parts of Oregon the fruit-raisers give all of their profits to the middlemen. They are little more than slaves toiling for their masters. Many of their farms are mortgaged. They can hardly call their souls their own. Their product is hawked about from one commission merchant to another until in despair they sell it for whatever they can get; and, worse still, even when the demand is good, and they figure on getting a living price, the deft manipulations of the middlemen exact full tribute from the luckless producers. The fruit is reported as having arrived at the market in bad shape, or some other of the many excuses used by the commission men in keeping their slaves' noses to the grindstone. In contrast to such a picture the true independence of the farmers of the Rogue River Valley is a birthright of priceless value. Democratic Times, Jacksonville, May 15, 1902, page 2 BARTLETT PEAR HARVEST ON.

Medford Crop Will Be Larger Than Last Year and of Fine Quality.

MEDFORD,

Or., Aug. 18.--(Special.)--The Bartlett pear harvesting began here in

earnest this morning. The pears are in excellent condition, and the

growers expect a much heavier yield than last year. The pear crop is

one which necessitates much care in handling and dispatch in its

shipment to market. The Bartlett trees are picked over three times

during the harvesting season, thus ensuring the best grades as to size.

The fruit is gathered quite green, and each pear is nicely wrapped in

paper, and is ripened during the period of shipping and being placed on

the market.

Large crews of men are at work in the orchards of Weeks & Orr, Gordon Voorhies and E. J. DeHart, and at the packing house of J. A. Whitman, the buyer. It is estimated that 45 to 50 carloads of Bartlett pears will be shipped from Medford this season. Morning Oregonian, Portland, August 19, 1902, page 4 The cost for picking, packing, wrapping, etc.--that is from the tree to the car where the station or siding is near the orchard--is from 25 to 30 cents per box. The paper alone for one year's crop will cost about $1,000, boxes $1,000 and nails $150. This will give some idea of the cost of a large commercial orchard. Pickers are paid $1 per day and board. Picking season lasts for about three weeks, and from 40 to 80 pickers are employed--50 being the average. The packing is done by girls. They employ about 16 who are experienced. It takes about two years to become an expert packer; some never can become expert in that line. The apples are picked off the trees by hand, placed in what are called orchard boxes and hauled to the packing house on long racks with springs under them, 60 to 70 boxes being hauled at each load, and they are stacked up. The red varieties are run through a polisher and are assorted into two sizes. The polisher is made by fastening brushes on a wheel, there being a circular strip upon which brushes are also fastened, all being attached to springs. The wheel is revolved quite rapidly, the apples passing through between the brushes on the wheel and those attached to the circular strip, which gives them a glossy appearance. The imperfect apples are set aside. The perfect apples are then wrapped in fruit paper, each piece having the advertisement of the orchard, and packed in standard boxes. The green-colored varieties are assorted, wrapped and packed, but not polished. A good packer under favorable circumstances can pack from 40 to 50 boxes per day of eleven hours. Ordinarily they pack from 25 to 30 boxes. The boxes are lined with paper, a blue cardboard is placed between each layer, and in [the] top and bottom of the box. The art in filling a box is in building it up, as each variety of apples is placed in differently. *

*

*

Olwell

Bros. have built up a reputation for honesty of

pack; hence they sometimes sell ten thousand dollars worth of fruit on

a telegraphic order. The buyer knows that he will get just what he

orders, and the seller knows that the buyer will be pleased."A Rich Orchard," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, October 2, 1902, page 4 A few years ago, not more than five or six, California fruit packers came over into Oregon and bought our pears, packed them in boxes bearing California labels, shipped them east and sold them as California-grown pears. A great howl went up at this, and the Mail sent up a protest that was louder than any of the howls. We, at that time, only hoped that a time would come when we could even up the score. That time has come--it is here now, and we are paying back the California pilferers--the whole indebtedness, with interest compounded. California apples are now being packed in Oregon boxes and sold as an Oregon product, and the price paid is better than that realized for the California product. The California fruit is undoubtedly as good, especially the apples grown in northern California, but they have not the reputation which the Oregon red and yellow apple has on the market--hence the packing of this fruit in Oregon-labeled boxes. It is also gratifying to note that the pears of Southern Oregon are no longer packed in California boxes. The excellence of our pears has forced itself into the markets of the world, and there is no longer a question raised as to quality where the Southern Oregon stencil or label is in evidence. As will be seen by the San Francisco market report, published elsewhere in this paper, Oregon apples are quoted in that city at twenty-five cents a box more than California apples. Medford Mail, November 21, 1902, page 2 "We grow Newtown Pippins and Spitzenbergs principally, and our climate, altitude and soil enable us to produce a better apple of that variety than can be grown in the eastern states. For that reason we can demand and receive a higher price for our fruit than can the eastern growers. There is always a plenty of the common grades of fruit; and it is by raising something extra good that an extra price is obtained. People who go into fruit-growing should study the conditions of their localities, so as to determine what variety of fruit will do best, and then not be content with growing anything inferior to the best that the conditions will permit." J. D. Olwell, "An Apple-Raiser on a Tour," quoted in Democratic Times, Jacksonville, December 31, 1902, page 1 Jos. Olwell, the clever horticulturist, has gone to Spokane. He has been invited to deliver an address at the meeting of the Northwest Fruit Growers' Association, which will be held in that city this week, on fruit packing in Southern Oregon, a subject he is well qualified to discuss. "Medford Squibs," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, February 4, 1903, page 4 From

the San Francisco

Chronicle.

It

is stated that California now ships about 350,000 boxes of apples a

year to Great Britain, and that with more care in packing, the sale

would increase very largely. A number of Oregon packers, who engage in

the business with the determination to perfect packing, regularly

outsell any California apples by about $1 a box. This is not because

the apples are better, but because the packing is better; the result is

that since but a few Oregon packers are in the business, all of whom do

good packing, Oregon apples have come to be regarded in the British

markets as "better" than California apples. Prestige earned in this way

is well deserved, and we respectfully take off our hats to Oregon; but

it is disgraceful that our California shippers should compel us to do

so.

Medford Mail, August

21, 1903, page 1

CALIFORNIANS WILL APE OREGONIANS.

They Are Going To Pack Their Fruit As We Do in Oregon-- Oregon Orchards a Treat to the Eye. From

the California

Fruitman's Guide.

A. S. Greenway, general manager in the United States of E. A. O'Kelly & Co., of London, returned recently from a trip to the apple sections of California and Oregon. He expresses himself as highly delighted and impressed with the appearance of the apple crops in both states. The Pajaro Valley, he ventures to predict, will turn out a much better crop than it has in the past three or four years. Newtowns show a good and full crop, and Bellflowers are even fuller. Mr. Greenway noticed that the Pajaro Valley orchardists are taking more care of their orchards; they are thinning out conscientiously, and spraying is now almost universal. "The Oregon orchards," said Mr. Greenway, "are a veritable treat to the eye. The crop is a good one. The Newtowns are a large crop, even if not so full as the other varieties, and the apples are looking remarkably fine and clean. "In California there will be less five-tier apples than ever before. The growers have learned their little lesson from experience and are hunting for four-tier stock. I look for a great improvement in the Californians' packing and grading this season and believe that they will emulate Oregon in these regards." Medford Mail, August 21, 1903, page 1

The

Rogue River Fruitgrower's Union has now taken up the principal object

for which it was organized, that of marketing fruit. The union has

leased J. A. Perry's big warehouse and fitted it up for a packing and

shipping room. . . . A large percentage of the fruit of this section

will be

shipped this season by the union, and it is quite certain that within a

year or two the bulk of the fruit of the Rogue River Valley will be

handled by the union. The union fruit all having one standard of

grading and being packed in the best manner possible, it will gain a

reputation in the markets of the world that will enable the union to

secure better prices than can be had by small shippers. The affairs of

the union are handled on the strictest business methods, and fruit men

will find that they have no occasion to find fault with their returns.

"Rogue River Fruitgrower's Union," The Daily Journal, Salem, September 1, 1903, page 3 THE LOST RING IS FOUND

And Now a Romance Should Follow.

A

few weeks ago, Miss Elsie Tucker, one of the young lady packers at the

Clay & Meader orchards, was unfortunate in having a gold ring

slip

from her finger while packing pears, and as she could not tell which

box of fruit it had fallen into [it] was given up as lost. Under date

of September 5th, A. J. Roadhouse, a fruit and vegetable dealer in

Jennings, Louisiana, writes Messrs. Clay & Meader as

follows:--"Will you please ask packer No. 3 if she lost a piece of

jewelry in packing a box of Bartlett pears? If so, let me know and I

will send it to her." Thus it seems that the ring has fallen into the

hands of an honest man and that the young lady will have it returned to

her.--Medford Mail.

Rogue River Courier, Grants Pass, September 24, 1903, page 2 Sale of Rogue River Fruit.

MEDFORD,

Or., Oct. 9.--(Special.)--The Rogue River Fruitgrowers' Association

shipped two carloads of Winter Nelis pears this week--one to

Cincinnati and the other to New Orleans, La. They also shipped one

carload of apples to New York.

E. J. DeHart just received returns from a carload of very fine Beurre de Anjou pears, which were shipped to Chicago. The pears were sold f.o.b. Medford for $1.50 per box, and Mr. DeHart was highly complimented on his methods of packing and the quality of fruit. Morning Oregonian, Portland, October 10, 1903, page 4 The picking of Newtowns and Spitzenbergs will not commence until October. The apples are left on the trees as long as possible, so that they may mature and attain perfect coloring. The rich coloring of the Rogue River apples has been a great aid in their marketing abroad at fancy prices. The fruit is carefully handled from the time of picking until it is placed on the cars. An apple which is bruised in any way becomes a cull. Throwing of apples from one hand to another in packing is not permitted, and apples are not rolled or dumped out of baskets or packing boxes. They are as carefully handled as eggs in each stage, from picking to shipping. After picking the apples stand 10 days before being graded. After grading they are stored in readiness for packing, and they are sent to the packers in the order in which they were stored--the first in, the first packed. The graded apples are trucked to the packers--a ton-load to the truck. The packing is done by girls, and they face windows which give abundant light. The packing houses are floored and are high above the ground. With side paper racks and box lining and layer paper in front of boxes, and apples at hand, the packers have everything needed in the right place. Each packer has a number, and that number is stamped on each box, as the packer is held responsible for the quality of pack. The apples are graded in size from the center each way, the largest being in the center and the grading down being uniform, so that each box has a big bulge. The apples are delivered to and taken from the packers by men. The packers are paid four cents per box, with a limit of 50 boxes per day. They work from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. A floor walker or manager has supervision of the packing and uniformity in size and quality of grading, and wrapping without a crease in the paper is insisted upon. The apples are carefully passed to the shipping wagons and as carefully loaded on the cars. In methods of picking, packing, grading and shipping apples the Rogue River Valley growers are not surpassed, and it is evident that the leaders in this great work and the persons to whom most credit is due for this showing are the Olwell Bros., pioneer orchardists and fruit handlers of Central Point and Medford. W. R. Radcliff, "Oregon Apples Growing," Rogue River Courier, Grants Pass, October 6, 1904, page 1 In another part of this paper is an article telling of the prices realized by J. W. Perkins for some fancy Comice pears shipped to New York City. The price paid per box was larger than ever heretofore paid in open market there. It was due, of course, principally to the extra quality of the fruit, but the packing also had something to do with the fancy prices. These pears, as stated in the article before mentioned, were packed in fancy shape, they were extra quality pears and as a consequence broke the record for high prices. Mr. Perkins, with other pear growers, claim that this valley is first of all a pear country. They are in all probability right. But we are of the opinion that fancy Newtown or Spitzenberg apples, packed upon the system followed by Mr. Perkins in his pear shipment would bring a price as comparatively larger than the ordinary price for apples, as the amount he realized was greater than that received from pears packed and handled in the usual manner. The proposition is simply this: If you have an article that is a little better than anyone else has and it is put up in a little better and more attractive shape than the other fellow puts it up, you can get a whole lot more money for it than he does. "A rose by any other name smells as sweet," but an article of food--from an apple or a pear to a porterhouse steak--brings the prices accordingly to the way it is put up. Medford Mail, October 13, 1905, page 4 Fruit-Grower

Subscriber Grows Record-Breaking Pears.

The fruit trade papers

have commented at great length upon a

record-breaking sale of a carload of Oregon pears in New York recently.

It develops that this fruit was grown and shipped by a member of The Fruit-Grower family--Mr. J. W. Perkins, of Medford, Ore. The record car of fruit consisted of about 1,000 half-boxes of Comice pears. The fruit sold at auction in New York for from $6.10 to $7.70 per box, the average being $6.80 per box, or $3,429 for the carload. This is the highest price ever paid for a carload of pears in this country. In packing this fruit Mr. Perkins used only half-boxes, holding 26 pounds of fruit each; these boxes were made from clear No. 1 lumber. He used a lithographed paper label on the end of the boxes, fancy lace-paper border and lithographed top mat. Experienced fruit men who saw the fruit before shipment pronounced it the "fanciest" car of fruit ever shipped from Oregon, and the prediction was made that it would be the finest car of pears ever received in New York. The price received for the fruit show that this prophecy came true. Mr. Perkins is in the famous Rogue River Valley of Southern Oregon, where fine fruit can be produced. Notwithstanding the favorable location, however, great credit is due to the grower for the care taken in producing fruit of this quality, and The Fruit-Grower congratulates Mr. Perkins in living in such a good country, and it also congratulates Southern Oregon upon having such an expert grower. Western Fruit-Grower, December 1905, page 22 ROMANCE HIDDEN IN PEAR BOX

Missive Deposited by Rogue River Maiden Secures Response from English Buyer.

Mr.

G. H. Lewis, a few weeks since, shipped a carload of Beurre Clairgeau

pears from his orchard, south of Medford, to London, England. Never but

once before has there been a shipment of pears made to this market from

the Rogue River Valley, and this first time the experiment was not

entirely satisfactory--in fact it was quite the reverse, and wholly

because the fruit was not iced en route, and when it reached its

destination it was in bad shape. This shipment, made by Mr. Lewis, was

in every way satisfactory, and while fancy prices were not received for

the fruit the experiment of shipping was very gratifying

notwithstanding the fact that the fruit arrived in London at a time

when the market was loaded down, and it was necessary to hold it three

days before putting on the market.

The Fruit Box Law.There were 860 half boxes in the shipment, and the net price realized was a little better than they could have been sold for in Medford--and Mr. Lewis has the experiment as an extra margin on the credit side of his account. There is a bit of romance connected with this shipment of pears--just a little strand of pleasantry such as packer girls have before been known to indulge in, but which oftentimes has proven a means of building a lasting friendship. When these pears were being packed, one of the packers, Miss Alma Gault, knowing they were to be shipped to England, wrote a little message to the consumer of the fruit, whoever he or she might be, and placed it in one of the boxes. That the message did not escape the notice of the purchaser of the fruit is conclusively proven by the receipt of the following letter: 46 Russell Street, Southsea, Portsmouth, Hants, England. October

17, 1906.

DEAR

MISS GAULT:

I opened a box of pears today (Wednesday) and inside I found your message. I was the individual that unpacked the pears and was very interested, so take the liberty of writing to you. I should think it a very pretty country where all those pears grow. They are so splendid that I have seen them sold at one shilling each. That is twenty-four cents in your money, and the people in London will think nothing of that price for a pear. I suppose they are much cheaper out there. I have never been to America. I have been to Cherbourg and Boulogne in France and in Scotland and in a good many large cities in my own country. I think your people know how to pack fruit. You must write and let me know what sort of place the States are. It must be a few months ago when you wrote that note, as I have had the pears in my shop for a month to ripen. Yours

sincerely,

Medford

Mail, November 23,

1906, page 1MR. MARK GOUSTICK. This year's crop packed out from 35 to 40 pears to the half box, of 70 to 80 to the full box of 50 pounds. Last year's carload was the first half-box packing ever shipped out of the state. These pears are packed in lithograph labels, lithograph top-mats and lace borders. The boxes are made of clear lumber. This is a very expensive way of packing fruit, but so successful that all the large fruit growers in the Rogue Rogue Valley have adopted the plan, so that the fanciest fruits that we ship are given the fanciest pack regardless of cost, and we have all found that the returns have justified it. J. W. Perkins, "What an Oregon Grower Has Done with Comice," Pacific Rural Press, December 1, 1906, page 340

The

following is the text of the law introduced by Representative Perkins

of Jackson County, which has passed both houses of the Oregon

Legislature, to require boxes of green fruit to be so marked as to show

the name and address of the grower and the name and address of the

packer:

Brand Your Fruit Boxes.Sec. 1. Any person, firm, association or corporation engaged in growing, selling or packing green fruit of any kind within the state of Oregon shall be required, upon packing any such fruit for market, whether intended for sale within or without the state of Oregon, to stamp, mark or label plainly upon the outside of every box or package of green fruit so packed the name and post office address of the person, firm, association or corporation packing the same. Provided, further, that when the grower of such fruit be other than the packer of the same, the name and post office address of such grower shall also prominently appear upon such box or package as the grower of such fruit. Sec. 2. It shall be unlawful for any dealer, commission merchant, shipper or vendor, by means of any false representation whatever, either verbal, printed or written, to represent or pretend that any fruits mentioned in Section 1 of this act were raised or produced or packed by any person or corporation, or in any locality other than by the person or corporation, or in the locality where the same were in fact raised, produced or packed, as the case may be. Sec. 3. If any dealer, commission merchant, shipper, vendor or other person shall have in his possession any of such fruit so falsely marked or labeled contrary to the provision of Section 1 of this Act, the possession of such dealer, commission merchant, shipper, vendor or other person of any such fruit so falsely marked or labeled shall be prima facie evidence that such dealer, commission merchant, shipper, vendor or other person has so falsely marked or labeled such fruits. Sec. 4. Any person violating any of the provisions of this act shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and, upon conviction thereof, shall be punished by a fine of not less than $5 nor more than $500 or imprisonment in the county jail not less than ten nor more than 100 days, or both such fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the court. Medford Mail, March 1, 1907, page 1

Now

that the fruit shipping season has begun, growers are confronted with

the necessity of complying with the new law, enacted by the last

legislature, requiring that every box or package of green fruit shall

be marked with the name and address of the grower and packer.

FRUIT

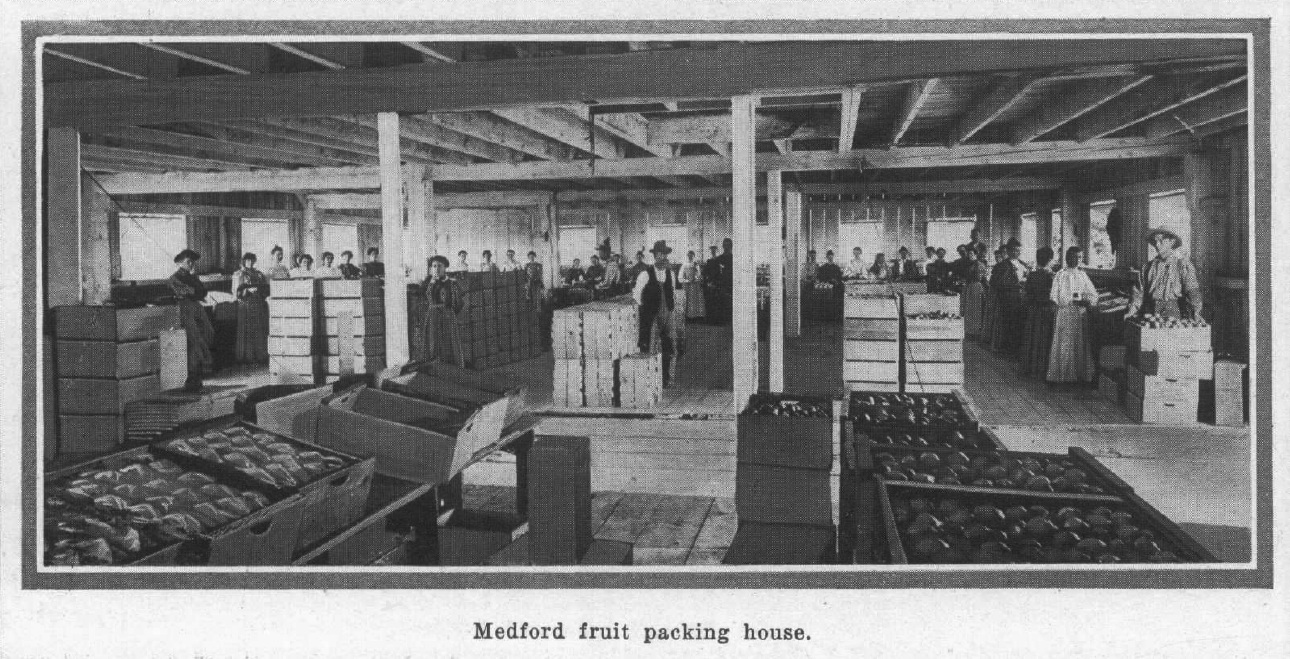

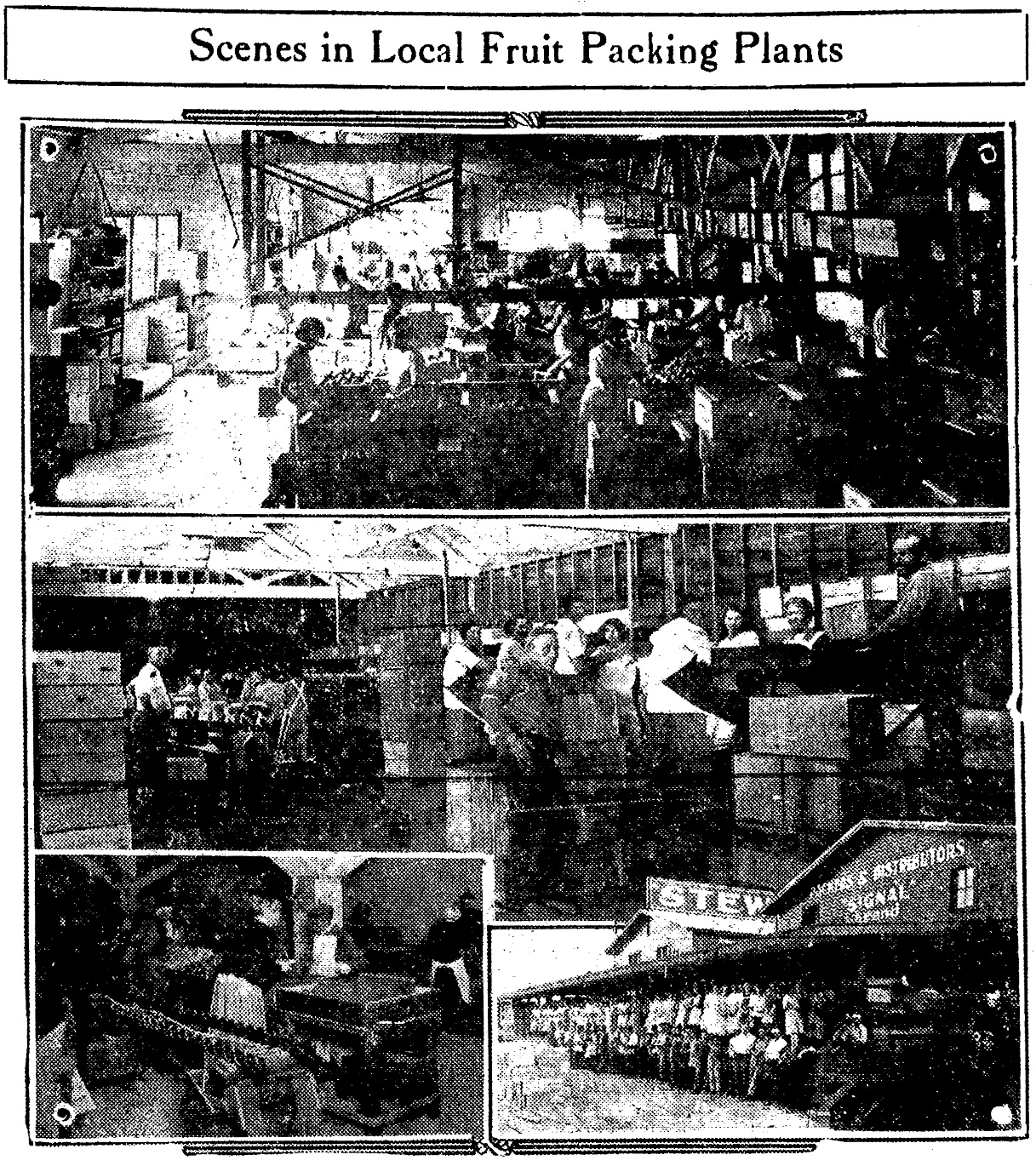

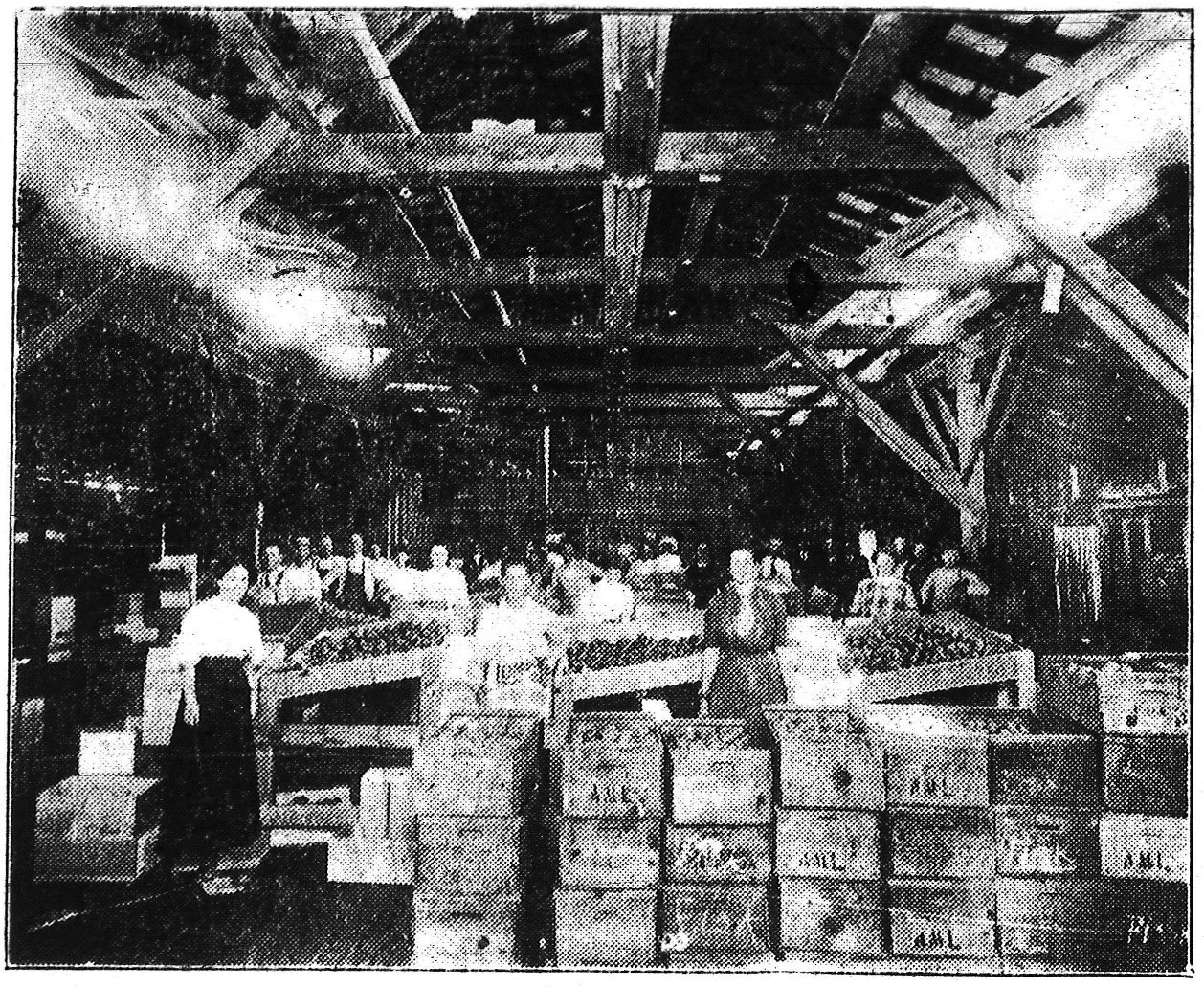

PACKING SCHOOL FOR ROGUE RIVER VALLEY."Any person, firm, association or corporation engaged in growing, selling or packing green fruit of any kind within the state of Oregon shall be required, upon packing any such fruit for market, whether intended for sale within or without the state of Oregon, to stamp, mark or label plainly upon the outside of every box or package of green fruit so packed the name and post office address of the person packing the same; provided, further, that when the grower of such fruit be other than the packer of the same, the name and post office address of such grower shall also prominently appear upon such box or package as the grower of such fruit." Medford Mail, June 7, 1907, page 3 So much depends on the quality of the fruit sent forward in determining prices, that the advantage is with the small grower, who personally superintends every detail. Everything connected with horticulture is an engrossing and fascinating study, and the man who gives it his undivided attention is sure to make it a success, is the opinion of Mr. Tronson. "Life of the Orchardist in the Rogue River Valley Appeals to H. B. Tronson," Sunday Oregonian, Portland, December 22, 1907, page C3  From

a 1909 Medford booster booklet. A newspaper article pointed out that

the photo is misidentified; this particular packing house apparently

wasn't in Medford.

A

fruit packing school is the latest move to raise to a higher standard

the pack and thereby add to the saleableness of Rogue River Valley

fruit. This commendable undertaking is being inaugurated by the Rogue

River Fruit Growers Union, and the arrangements are now being worked

out by manager J. A. Perry.

The Fruit Growers Union has two large warehouses in Medford, and one of these will be fitted up for the school and sufficient packing tables placed in it to accommodate a large class. The school will open about the 20th of July and will continue until the regular packing season opens, which will be about August 12 when the Bartlett pears are ripe. The only fruit that will be available will be early apples, and these will be used in the demonstration work. The apples will be used over and over so long as they are usable and will be supplied by the Union, as will be all other equipment. There will be no tuition or other charges to be paid by the scholars, all being free to them. Those that attain the required degree of proficiency in packing will be given a certificate. Packers holding these certificates will be given the preference by the manager and the members of the Union when making up the packing crews for the season's work. An apt person can learn the method of packing in one or two days, but it takes long practice to become a fast and expert packer. The average packer earns from $2 to $3 a day, but there are packers who sometimes earn as much as $5 per day. It would be well for those desiring to attend the packing school to file their applications so soon as possible with manager Perry. In selecting packers the preference will be given women and girls, though men and boys will be employed, but no girl or boy under 16 years will be accepted. The reason for giving women and girls the preference is that they usually are more painstaking and put up a more attractive pack than do men. The boys are credited with being the poorest packers of all, for they are too inclined to play and be careless and not willing to strictly follow orders. The value of strictly first-class and honest grading and packing has been demonstrated in all the markets of the world. To get such a pack and the reputation and the price that will come of it is the aim of every fruit growers' organization in the United States. The Hood River Fruit Growers Union is the first association to attain a pack that is recognized as perfect by the buyers, and for the past three years the Hood River apples have been sold without inspection in the markets of New York and London, and at record prices. The Hood River guarantee is recognized by all the buyers, and not a box is ever opened to ascertain if there is an imperfect apple in it, or that the bottom layer may not be up to the standard of the middle layer or the top layer. This is a distinction not had by any other fruit growers' association or individual grower in the United States, and it is proof that it pays to be honest in grading and careful in the packing of fruit. To secure this remarkable high standard in grading and packing it was necessary for Hood River Union to have the entire control of the packing, the growers having nothing to do with this work other than to furnish the packing houses, the equipment and the helpers to handle the boxes. And to secure a corps of graders and packers that could do the exacting work required, the Hood River Union has for several seasons past conducted a training school for beginners. While the standard of the Rogue River pack is high, yet it is not so high but that dealers in the East and in Europe insist on inspection before they will buy a box of fruit. With the establishment of a school for packers and the enforcement of more rigid rules in the picking, handling, grading and packing that have been lately been adopted, the time is not distant when Rogue River fruit will be sold without inspection and at prices much higher than heretofore had. Rogue River Fruit Grower, May 1909 WILL ESTABLISH SCHOOL. Fruit Growers To Teach Packing of Fruit Scientifically

A

special meeting of the Rogue River Fruit Growers' Union was held

yesterday, and a large portion of the membership was in attendance.

PRECOOL

FRUIT FOR SHIPMENTThe main subject discussed at the meeting was the establishment of a packing school. It was decided to establish such a school at the packing house during the season, where the art of packing all kinds of fruit will be taught the boys and girls, and when they become proficient in that line a certificate will be given them, entitling them to a preference in their employment by packers. All have so far showed their willingness to raise the standard of teaching. The annual meeting of the association will be held on the last Saturday of the month, when the matter of providing boxes and other packing material will be taken up. At the annual meeting an estimate of the crop of each member will be required. The commission last year to the union for packing was 6 percent for 2000 boxes and under, and 4 percent for over that amount, and at the annual meeting the rate of commission will again be established. The order for the lithographed labels for the boxes will be given after the annual meeting. All fruit growers who are not in the union are invited to become members at an early date. Medford Mail, May 14, 1909, page 1  Advice by Prof. G. H. Powell of Great Value to the Fruit Growers

The

visit of Prof. G. H. Powell, the special representative of the

Department of Agriculture at Washington, to Medford and the Rogue

Valley promises to "bear abundant fruit," as it were, for he gave some

valuable information which is sure to prove of great value to the fruit

growers.

FRUIT

PACKING SCHOOL.Prof. Powell's specialty is precooling, and he has spent the last seven years studying and experimenting along those lines. Just what this means in theory and practice is explained by Prof. P. J. O'Gara, who has been in close touch with Prof. Powell both before and during his visit here. Picking and Handling.

To begin

with, the most important

matter is that regarding the picking and the handling of the fruit,

more particularly what is known as perishable fruit. That is peaches,

apricots, pears and grapes. Then, next to that, oranges and vegetables.

With all of these, the most extreme precautions must be taken both in

the picking and the packing.The department has experimented in all with 1200 cars. Out of that it has been found that about 80 percent has been damaged more or less in the picking or the handling. When the department first took the matter up, the growers claimed that the trouble was in the soil, but they were shown that perfect fruit would not rot under proper conditions unless it was damaged. This means not only getting the fruit to the market in good condition, but having it remain that way for a reasonable length of time. System of Precooling.

In the

system of precooling it

means that the growers and shippers can not only get the fruit to

market in good condition, but under normal conditions it would keep

from 60 to 90 days. So well impressed have the railroad companies

become from what has been demonstrated in this line that it is

understood that the Southern Pacific Railway company is contemplating

erecting two precooling stations along the line in California.The plan is in the precooling to bring the fruit down to a temperature of between 36 and 40 degrees before it is shipped on board of the cars. Then it is all cooled through, whereas it is claimed that when the fruit is placed in the cars and cooled there that if it is wrapped only the fruit on the outside is thoroughly cooled. As to the benefits to be derived, it can be stated that if the fruit is placed in the refrigerator cars while it is warm that the car will require icing from five to seven times during transit to the East, while if it is precooled it will usually carry to its destination with only one icing on the way. On that account two cars could easily carry what it takes three cars for now. It is claimed, therefore, that between the matter of less icing and the greater carrying capacity of the cars that there would be a great saving in the shipment of the fruit by the precooling process if it were put into practice. Advocates Confederation.

Prof. O'Gara also claims that by getting

a

confederation of all the different growers' associations that the fruit

could be placed on the markets through their own agents in place of

letting the middle or commission men get the cream for handling it just

as they please. It also says that the precooling system is only in its

infancy, but that it will soon become a great factor in the fruit

industry when it has been thoroughly demonstrated to the growers and

the shippers.Excerpt, Medford Mail, July 30, 1909, page 1 It Will Open Next Thursday in the Union Packing House.

The

Rogue River Fruit Growers' Union will open its fruit packing school in

the Union's packing house in Medford on Thursday next. The Union

expects to pack and ship a few carloads of early apples and pears, and

it is upon this fruit that the students will be put to work. There have

been already upward of 50 applicants made to enter this school, and

there will undoubtedly be a great many more before the school starts.

Mr. Perry, the manager of the Union, has half a dozen first-class,

experienced packers who will be instructors in this school. The

students will not be shown how to do correct packing by watching the

work done by experts, but they will be compelled to pack the fruit

themselves under the direct supervision of the instructors. It is

expected that these several carloads of early fruit will be packed and

repacked several times before the fruit will be considered in proper

shape to go on to the markets. The school will continue until about the

15th of August.

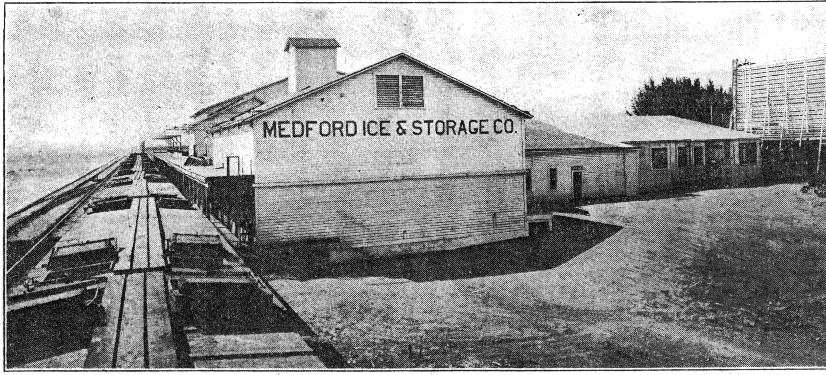

Medford Mail, August 6, 1909, page 1  Medford Ice, from the January 2, 1927 Medford Mail Tribune WILL BE ICED HERE

Fruit Cars Will Be Supplied with Ice by Local Concern

The

management of the Medford Ice & Storage Company are making

preparations so as to be able to fill a contract with the Southern

Pacific railway to supply a large quantity of ice during the summer for

the fruit refrigeration cars. It is expected that they will supply with

ice from 300 to 500 cars during the fruit season.

Formerly all the icing of the cars was done elsewhere, but for certain reasons the company are changing that arrangement and will have all the fruit cars which are loaded at all places between Central Point and Phoenix supplied with ice at the plant of the Medford Ice & Storage Company, which is situated on the railroad track at the south end of the city. In order to be able to handle the work promptly a two-decked platform is being erected all along the railroad side of the building, 153 feet long and nine feet wide. The factory is already supplied with elevators, and the ice will be taken to the top platform and from there placed on the cars as they are run alongside on the sidetrack. The first car will be loaded next Monday. It will be a carload of Rogue River valley pears. From that on it is expected that not a weekday will pass without one or more cars being stocked with ice for the journey to the eastern markets. Although supply a large amount of the finest quality of ice to city customers and several outlying places, the Medford plant is equipped so as to furnish the cars as well without the slightest extra effort on the part of the staff. It might also be mentioned that all the ice is made only from the best distilled water and is perfectly pure. Medford Mail, August 13, 1909, page 4 FRUIT PACKING SCHOOL.

The

fruit packing school is progressing finely, there being about 20

students in attendance every day. Several have already graduated, and

new ones are constantly taking their places. This school is costing the

fruit union about $25 a day, but there is satisfaction in expending

this money in knowing that when the busy packing season begins the

packers will not then be students--and the fruit--will be packed right.

FRUIT PACKING SCHOOL.Medford Mail, August 13, 1909, page 6 PACKING FRUIT IN ROGUE RIVER

VALLEY, OREGON

On the general principles of picking, practically all growers agree. A

great many, however, are careless in the handling, the fruit often

being needlessly bruised. It does not matter a great deal whether

buckets, baskets or sacks are used to pick in, but the essential

requirement is that the fruit be picked and transferred to the box very

carefully. BY C. I. LEWIS, S. L. BENNETT AND C. C. VINCENT, CORVALLIS, OREGON A few of the growers practice the method of using their packing boxes for field work. The market demands good clean boxes, and it is almost impossible to take boxes into the orchard to be dumped around, filled and hauled into the packing houses without getting them more or less soiled. Hence, by all means, orchard or picking boxes should be used. Of late the subject of wiping the fruit is attracting considerable interest, and many questions were asked, such as, "Does wiping injure the keeping quality of the fruit?" "Does it pay to wipe apples?" It always pays to wipe fruit if the trade prefers, as they generally in such cases realize more than enough to repay the additional cost. If wiping is done in the proper manner it will not impair the keeping quality of the fruit. Severe rubbing would probably be an injury, but if the unnatural spots and color resulting from the presence of sprays, etc., are removed, this is all that is necessary, though if the fruit is to be sold for immediate consumption, a higher polish would probably be of material aid, since the market appreciates this extra effort. This wiping should be done immediately after picking, on account of the sweat or oil that may gather on the surface of the fruit. The fruit should be carefully culled and graded before reaching the packer, because first-class packing cannot be done if it must be graded and sorted at the same time. This, as well as the wiping of the apples and pears, may be done as soon as the fruit is brought from the orchard, and then placed in packing boxes for storing until packing begins. Quite a large number of growers were found to pile their fruit in bins, but this is very detrimental indeed. It admits of a great deal more sweating, due to poor ventilation, and also of considerable bruising in handling. It is a very commendable feature that many of the growers are using the lithograph instead of the old method of having an ink stamp on the end of the box. Another plan which should he followed is to stamp on the other end of the box the number of apples, pears, etc., which it contains, as well as the number of tiers. The writers believe that better grading can be done if, instead of packing the apples on side benches, where the fruit is packed from single boxes, the packers had a large amount of fruit to pick from. This would mean a modification of the benches or else the adoption of tables. Certain it is that better grading can be done from large quantities than from small quantities. The packing of any fruit is largely a matter of experience. There are certain principles which apply to all fruits, though more care must be exercised with some varieties than with others. The pear is a very perishable fruit and requires the most careful handling. It must be picked while yet in the green state. Although the picking season varies with the prevailing climatic conditions each year, August 15 is about the time for the harvest to begin. Whenever, on slightly twisting the stem and turning the pear upward, it will snap off, the fruit is ready to pick. This generally means several pickings from the same tree. This method relieves the tree and gives it an opportunity to mature the remaining fruit to best advantage. Great care must be exercised not to have the pears hang too long, for it deteriorates the shipping qualities quite materially. After picking, the pears should be packed and shipped as soon as possible, as they are quite perishable. The principles of culling, grading, etc., are the same as those of other fruits. The boxes are shorter but wider than the apple boxes, having the following dimensions: depth 8¾ inches, width 12 inches, length 18¾ inches. They must he packed with lining, layer and wrapping paper. There is an increasing demand for pears packed in the half-size boxes. This means a very fancy price if a handsome lithograph is placed on the top layer and lace paper lines the edges, with an additional lithograph on the outside of the box. This only makes a slight increased cost, and the fruit sells at a very large advance over the ordinary pears. It is understood that the fruit itself must be first class. It is a splendid illustration of the statement that the greatest profit is realized by handling a number-one product in a first-class manner. There are several forms of packs, but all are diagonal. The first pears are placed in the box with the stem from the packer, the calyx to the end of the box. In what is known as the three-two packs there are three of these, one in the middle, the other two being at the sides. Then a pear is placed in each of the two intervals formed by the three and with the stem pointing toward the packer. Then alternately, three and two, the remainder of the pears in the tier are placed in the same way, there being twenty-three pears in each of four tiers, or ninety-two per box, when packed in the full-sized box, or forty-six in the half-boxes. With the four-three pack there are twenty-eight, and with the three-three offset twenty-four pears in a tier. The pears must be packed tight, so that when the box is nailed there will be pressure enough on the fruit to hold it firmly in place. A larger bulge is allowed on pears than on apples. Packing Peaches--At the Ashland Fruit Growers' Association peaches were being packed in boxes 4½ inches deep, 19¾ inches long and 11¼ inches wide. A three-quarter-inch space is left between sides and top and bottom. Holes are also bored in the sides of the boxes to allow circulation of air. These boxes allow two layers of peaches, and in nearly all grades every peach is wrapped. Although the fruit is very hard when packed, care must be taken not to bruise it in any way. The peaches must be packed in such a way that they are held firmly in the package, and under no condition must rattle. The peaches are delivered in clean one-half bushel baskets and the grading is done at the time of packing, Most of the packing is done by women and girls, who are allowed two cents per box. Each packer puts up from sixty to eighty boxes per day. Two grades are made according to quality, the second grade being marked X. Grades are also made according to size. Fancy contain sixty-four or less to the box; A, sixty-four to eighty; B, eighty to ninety; and D contains the small and low-grade peaches and are unwrapped. The cost of putting up a box of peaches, including material and work, is about nine cents. From sixty to eighty carloads of peaches are shipped annually. Twelve hundred of the twenty-pound boxes can be loaded in a car, and at this rate it would cost about fifteen cents a box to send as far east as Kansas City. Better Fruit, September 1909, pages 28-29 Will Be Held in Medford from September 13 to 24.

All

fruit growers should, and doubtlessly will, be interested in the

fruit-packing school which is to be conducted in this city from Monday,

September 13, to September 24. Two instructors have been secured for

the work from the Oregon Agricultural College at Corvallis. The place

where the school will be held is the Cox warehouse, on South DeAnjou

Street. The room is sufficiently large to accommodate 20 students at a

time.