|

|

Jackson County 1856 Also refer to Capt. T. J. Cram's report. FROM OREGON--THE INDIAN WAR.

Rogue River Valley,

March 31, 1856.

To the Editor of

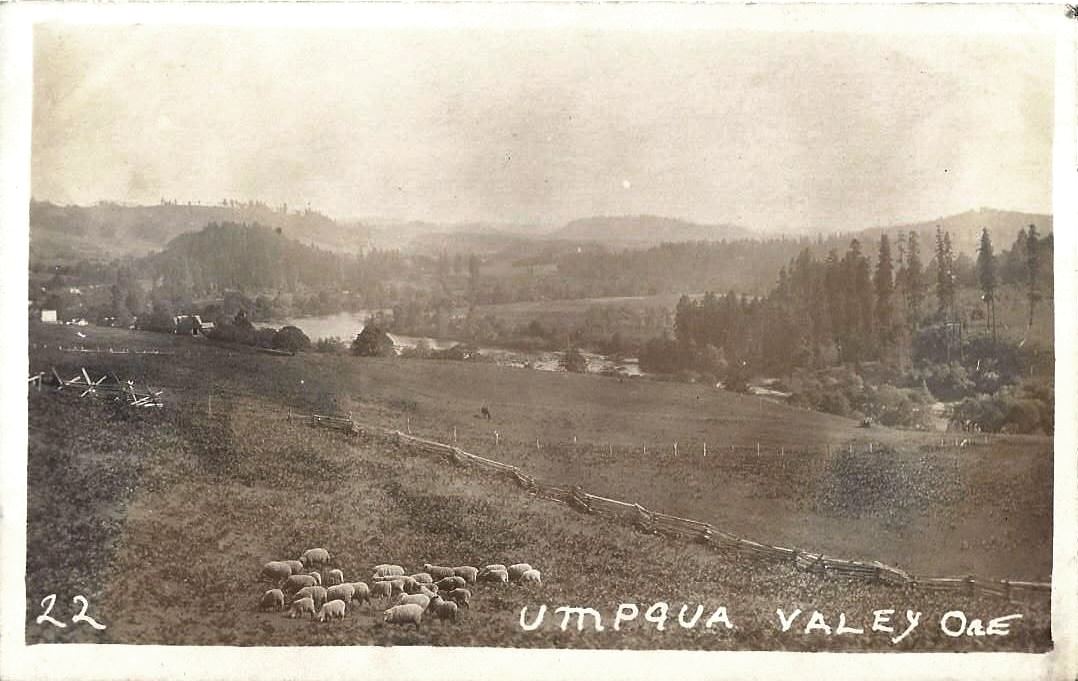

the National Era:As I am sending you the names of some new subscribers, with a cash "accompaniment," I avail myself of the opportunity to send you a few lines which may be of interest, if from no other reason, because of the remoteness of the locality from which I write. Jackson County, Oregon Territory, in which is embraced Rogue River Valley, contains a population of some three thousand inhabitants. It is the southern extremity of the Territory, and almost isolated from the rest of Oregon. Rogue River Valley, which contains the principal portion of the farming community, is completely surrounded by a cordon of almost insurmountable mountains, and is connected with the Umpqua Valley by the main road leading from the Sacramento Valley, California, to the Willamette Valley, Oregon, which, after leaving Rogue River, and for a distance of some forty miles, penetrates a barren mountainous country that only admits of a settler at long intervals, and finally, after defiling through a deep gorge or cañon in the Umpqua Mountain, emerges into the Umpqua Valley. The nearest accessible point on the Pacific Coast is Crescent City, California, distant one hundred miles, which is only reached over a rough mountainous pack trail, and over which the heavily laden pack mule groans with his burden of supplies for miners and farmers. Now, whilst all eyes in "the States" are turned to Kansas, and her citizens are defending themselves against the attacks of the "border ruffians," we here, thus pent up and isolated, are defending ourselves against the insidious attacks of a merciless savage foe, who are menacing our borders, and destroying the lives and property of our people. For the last six months, we have been engaged in an Indian war, during which time scores of our citizens have fallen--some in the conflict of battle, and some when least suspecting danger have been shot from their horses while riding along the highway; families have been butchered, and their horses burned over them. Nor does there seem any more prospect of an end to these troubles now than there did three months ago; in fact, it looks darker, and everything seems to indicate and bid fair for a protracted war. Within the last few days our troops have had several skirmishes with the Indians, but have almost invariably been worsted. In one instance, the Indians captured some forty horses, with their equipments, and within the last few days, they have cut off several large pack trains, which were loaded with supplies, ammunition &c., for the valley. The force in the field is entirely inadequate to the successful prosecution of the war. It is, in fact, not more than sufficient for the protection of the settlements. The Indians are well armed--better, indeed, than the whites, and they know how to use them to as good advantage. They have chosen their retreats in the mountain fastnesses almost inaccessible to the whites, and in localities where they can get subsistence easily, and from whence they can sally forth, commit their depredations, and retreat unmolested. It is obvious that unless we have a force sufficient to make some offensive demonstrations toward the enemy, that the war must be protracted to a ruinous length. Many of our citizens now have invested their all in furnishing subsistence for the volunteers, and there is scarcely anyone that is not more or less involved. Unless we have help, and that speedily, our country will be ruined--the capital all absorbed, and the war not terminated. It would certainly be good policy for Congress immediately to make appropriations to meet the expense of the war. All supplies are only obtained at high rates, for the reason that if the indebtedness is paid at all, it will be twelve or eighteen months, at least. Government is but a tardy paymaster at best, and the people of this country know it to their sorrow, some of them. Yours,

National Era, Washington,

D.C., May 22, 1856, page

2J. W. McCALL. Reminiscent Sketches by a Pioneer

Methodist Preacher

Rogue River Fruit Grower, November

1910INTRODUCTORY

The subjoined article is the first of a series that

will be written by Rev. Charles

H. Hoxie for the Rogue

River Fruit Grower. These

articles will deal with pioneer times in Rogue River Valley and will

cover features and incidents that will be highly interesting to all who

are interested in the early history of this valley.

Rev. Hoxie came to Rogue River Valley in the spring of 1855, in company with his mother and brother, James, and his elder brother, George. The father and son [George] had left the New England home in the fall of 1849 for California, being attracted by the gold discoveries made the previous year. They shipped from New Bedford on the whaling bark Chase, and they were until the following summer reaching San Francisco, an extended stay having been made by their vessel in the seas about Cape Horn while capturing whales. From San Francisco Major Hoxie and his son went to the gold mines, and in 1851 they located in Yreka, where they opened a store and conducted it for a year, when in the fall of 1852 they came on north and each took up a donation claim on the west bank of Bear Creek, midway between the present towns of Medford and Phoenix. Of this pioneer family the Major and his wife, who both were said to have been persons of noble traits and much respected by their neighbors, have gone to their reward in the beyond. Of the sons, George now resides in Williams Valley, where he is spending his declining years on a fine farm after an active life in the ministry of the Dunkard Church, he yet preaching from time to time sermons that are polished and forceful. James, the second son, is enjoying a comfortable home on his farm near Wilderville, while Charles, the youngest, is now residing in Medford after 48 years of service as a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church. In this nearly half century of ministerial work as a Methodist circuit rider, Rev. Hoxie has preached in every section of Southern Oregon, there being hardly a church or a school house, except those erected within the past few years, but what he has held services in, and in pioneer days when churches and school houses were few and far between he held religious services in many of the homes of the settlers. His reminiscences of the wedding and funeral services that he has held would make chapters, happy or sorrowful, in the history of many pioneer families of this valley. His circuit usually embraced several places at which he preached, and to reach these and to make his pastoral calls and to attend to the other duties incumbent upon a pioneer Methodist circuit rider made it necessary for him to be on the road almost every day of the week, he even having to travel on Sunday, for frequently he had two appointments for the day. Roads were few, and in the winter were nearly impassable with mud, and the trails were mostly steep and rough, making it necessary that he do his traveling on horseback. Thus it was that the saddle was his only place for study, and it was on the long, lonely rides that he got time to think out the points for the sermon or address that he next was to deliver. While he had many hardships by reason of bad roads, storms, fording swollen streams and other trials, yet there were many pleasant features to his itinerant life, for though the conveniences in the pioneer homes were few and rude, the noble hospitality of the settlers made him and every other traveler welcome at any hour, day or night. As was the case with all those pioneer itinerant preachers, Rev. Hoxie thoroughly enjoyed his work, and despite the small salary that sufficed for his living expenses and the trying hardships, he looks back with pleasure on the many years that he put in carrying the gospel of a better life to the struggling, lonely settlers of a new country. ------

About the first of

November, 1855, in company with my mother and James, an older brother,

I left New Bedford, Mass., by railroad, for New York to take passage on

an ocean steamer for San Francisco, Cal., to meet my father--who had in

the spring of 1849, with my oldest brother, George, an uncle and a

cousin gone to California around Cape Horn and had settled in the Rogue

River Valley in the fall of 1852--and by him to be taken to our western

home in the then far away Southern Oregon. We took the ocean steamer George Law for

Aspinwall (now Colon), where after the usual experience of a sea voyage

and the common incidents of steamer life, we arrived without accident.

We rode across the Isthmus on the slowest-moving cars we had ever

traveled upon [since] in boyhood days, and at the terminus, Panama,

took the steamer Golden

Age on the Pacific side for San Francisco, where we

arrived, in company with thirteen hundred passengers, on Thanksgiving

Day, 1855.Owing to my father being in the volunteer military service of the government, which had called for volunteers to suppress an Indian outbreak extending over all the northwest coast, we were detained in San Francisco for six weeks. At the expiration of this period my father arrived overland from Rogue River Valley, and in a few days we took the ocean steamer Columbia for Portland, Oregon, where after a run of three days we arrived safely. We left that city, then a village built among brush, fallen timber and rotten logs, the following morning after our arrival and took passage on a river steamer for that historic town, Oregon City, where we spent the night. The next morning we were transferred across the portage between the town and upper part of the falls, where we took another boat running on the upper Willamette, when we proceeded to Corvallis, passing on our way the then-center of Oregon's educational interest and capital of the territory, Salem, since becoming the capital of the state, and also Albany, it being on the banks of the Willamette River and county seat of Linn County. At Corvallis my father took in charge ten horses, the property of the government, four of which were ridden by our party and three led by each of us boys, which were to be delivered to the proper authorities at Roseburg for the use of the volunteers of the Rogue River Indian War. At Roseburg we were furnished with an escort to the valley, as it was considered unsafe for small parties to travel from the southern end of the big canyon [at Canyonville] to Jackson County. It required two days to reach the old town of Canyonville, being under the shadows of the hills at the northern entrance of this natural passage between the Umpqua Valley and Cow Creek Valley. We spent the night at this historic town, and after an early breakfast mounted our horses and filed into the trail leading through the gorge, between a rock weighing many tons and the hill. When in regular order we began our march towards its southern entrance. Late in the afternoon we reached Hardy Elliff's and fed our horses, refreshing our own inner man with venison steak, hot biscuit and coffee. Here my mother donned my father's blue soldier coat and my brother's cap, and when all were ready took her place between my father and us boys to make the company look as formidable as possible, for we had a ride of several hours before us through a country in which hostile Indians might be lurking to pick off the unwary traveler, before we could reach Grave Creek, our destination that night. After a long and wearied ride we reached Harkness' and Twogood's cabin on Grave Creek, near where the present town of Leland is located, at about two o'clock the next morning without meeting or seeing any indications of Indians. In a large room, whose floor was nearly covered with sleeping volunteers, Father and Mother found space in a corner to catch a few hours' sleep, while we boys lay down nearby. The morning light found a room whose only occupants were Major Hoxie and wife and two mischievous boys from the Bay State, a consideration of the soldiers for a woman's position. From Grave Creek to where is now located Grants Pass there were but few houses, and what had been happy homes where childhood's smiles and youth's ringing laughter blended with love's stronger expression of mature years, was but blackened debris, the work of the Rogue River Indians.  Circa 1910. On the evening of the 15th day of February 1856, we arrived on the bank of Rogue River, at just below where the beautiful town of Woodville now stands, if I recollect aright, and crossed from the east to the west side by a ferry, called Jewett's Ferry, I believe. We then proceeded a couple of miles up the river and stopped for the night at the home of David Birdseye, now deceased, but his widow yet resides on their old donation claim. The next morning was ushered in by dancing sunbeams and balmy air, which we had not seen nor felt for long, dreary weeks. This and the fact that we were within a few miles of our new western home, to reach which we had traveled 3000 miles by land and water, made our party very happy, and we were up early, and after enjoying the appetizing breakfast that Mrs. Birdseye prepared for us we mounted our horses for the ride to my father's claim, which he had taken up on the west side of Bear Creek a mile and a half south of the present town of Medford. At what was known as The Dardanelles, opposite of which is now the town of Gold Hill, we left the river bank and began to ascend the gentle slope along which the road ran and which led over the Blackwell Hills into the valley proper, now known around the world, its fruits being the delight even of sovereigns across the oceans. Arriving at the summit of the hill, what a scene of loveliness suddenly burst upon our view! It would require the descriptive powers of a Dickens to convey to the mind of the reader its wonderful beauty; and the brush of a Michel Angelo could not transfer it to canvas. Like a magnificent gem in its setting, the valley stretched away before us, encircled by its eternal hills. Within those encircling hills, until but a brief space of time before, silence as profound as death had reigned for centuries, only broken by the yell of the aborigines, or the cry of prowling wild beasts. Across and through its luxuriant growth of herbage the timid deer passed from hill to hill unterrified by crack of rifle or the whizzing bullet of the revolver. To our left, within almost rifle shot, stood those twin sentinels, the world-renowned Table Rocks, with a mantle of green covering their rugged sides, in all the majesty of guardians over this fair gem of the Northwest. And there they had stood since volcanic action had scooped out Crater Lake and created this piece of nature's loveliness. And what thoughts are suggested to the cultured Anglo-Saxon mind as one gazes upon those wonderful products of nature, which for ages had listened for the first sound of the footfall of civilization in its approach, to claim by right of development and harmony of nature and mind this fair jewel which had only been a plaything in the hands of barbarians. Upon the top of these mighty rocks the signal fires of savage life had thrown their life into the murky darkness of the night for untold ages, and Indian children had played around the tepee, practicing the war whoop, indulging in feats of physical strength in view of their becoming braves. At their base, like a silver thread running through a warp of green, Rogue River wound its way to the sea. In their season the denizens of the sea, on their way to their spawning grounds, might be seen sporting in its limpid waters, or resting in the stillness of an eddy among the roots of an overhanging tree after their sport, while the ripple caused by their action broke upon the distant shore or kissed the higher embankment. At the southern extremity of the valley, like a king upon his throne, high up among the Siskiyou Mountains stood Pilot Rock, another of those wonderful marks carved by the hand of nature, to be found upon the Pacific Slope. This ragged peak looked like a monarch which had guarded the southern entrance to his possessions until time had torn his crown from his head and dashed into a thousand fragments at his feet, while the elements had stripped him of his robes, leaving nothing but a skeleton of his former majesty. (To

be continued.)

(Continued

from the November number)

To the east

could be seen with his winter mantle wrapped closely around his head,

shoulders and part of his body, which glittered in the rays of the sun,

a titan rising above his fellows, the glory of Southern Oregon, known

upon the map as Mt. McLoughlin or Mt. Pitt, but to the old settler as

Snowy Butte. The summer sun would throw off his snowy mantle and in

rivulets send it purling down its sides to form lakes as reservoirs, or

join rippling streams to join Rogue River and the ocean, but within the

past year diverted into a pipeline and brought to Medford to supply

that town with pure mountain water.

With the squeak of the chipmunk and the whirr of the pheasant and grouse falling upon the ear, while here and there bands of cattle and horses were grazing upon the rich and nutritious bunchgrass, springing up among a luxuriant growth of the previous season, while ever and anon the wild flowers turned aside their heads to escape the kiss of the sun's rays, or appeared to be playing hide and seek among the dead grass as a gentle breeze passed over them. Above the valley, circling in air, were thousands of the feathered tribe, which had in the fall left their homes in the frozen north to take an outing in a milder climate. It was a rare scene of loveliness unrivaled by any scene in nature in any country, that we beheld that day as we crossed the Blackwell Hill and first beheld the main part of Rogue River Valley. But we could not tarry long even amid such an enchanting scene. Descending the hill we pursued our journey along the only road through the valley, with waving grass on each side of us, and arrived at the terminus of a journey of three thousand miles, which had been borne by my mother with discomfort, inconvenience and a painful memory of leaving the comforts of civilization and refinement for a wild life upon the frontier of Uncle Sam's domain. We arrived late in the day, and found our residence was to be a log cabin of usual size in a new country, with its chimney of rock foundation, while the chimney itself was of sticks crossed upon each other, with mud between and plastered with mud on the inside. There was one room divided by rough boards into two bedrooms, one a little larger in size, which was again divided by a curtain. The roof was covered with shakes or clapboards. There was a narrow porch in front, covered with shakes and supported by small, peeled fir poles. The barn, which would hold about one ton of hay, and accommodate three horses, was small, being made by setting posts in the ground and covering sides and roof with the ever-handy shake, but with no hay to put in it. In a few days after our arrival my father built additions to the original house, putting a small room on the back of the house and also a small room on the north end which was used as a kitchen. To this room was attached a woodshed, made entirely of rough slabs hauled from a sawmill built by E. E. Gore on the bank of Bear Creek, opposite the present residence of his son, John Gore, and but a short distance above us, being about two and one-half miles south of the present city of Medford, and at that time managed by a gentleman by the name of Jack Forsythe. There was but little fencing done in the valley, and the little was the old worm or Virginia fence. The valley was held as common pasture ground for those who had stock. WILD ANIMALS AND

REPTILES.

There were but

few wild animals to be found in the valley after our arrival, bear

seldom being seen, although a wildcat would be killed

occasionally

along the creek. The most ferocious animal was the cougar, two of which

I know to have been shot, one by my cousin Charles F. Jones and the

other by my father upon a bright moonlight night, while trying to get

chickens from a hen prison in which my mother kept refractory hens, and

was shot from the old slab woodshed. Of course we had the common

animals belonging to all new countries, such as the skunk, coyote and

some other species. There were some snakes in the valley, most of which

were harmless, but sometimes the rattle of the deadly rattlesnake was

heard. I know of one case of death from the fangs of this dreaded

reptile, a young daughter of William Justus, an old settler living

about a mile west of the present Burrell orchard.

GAME.

Game was

abundant. From fall to late spring the depressions in the valley were

filled with water from the winter's rain, and these would be covered

with wildfowl from the stately swan to the diminutive wood duck with

his beautiful plumage of purple and gold. Mingling with others, the

canvasback duck, that toothsome bird of the epicure, could be seen,

while single and in flocks the pride of Oregon, the mallard or

greenhead would circle just above the traveler's head or be seen upon

the surface of the water in some pond. Many kinds all mingling together

as one flock might be seen circling in the air unalarmed by the present

of persons near them. Hundreds could have been shot in a day, instead

of the few that were killed. We killed a great many which furnished

meat for the table. Mother, being a New England woman, utilized the

feathers by making several feather beds according to the old idea of a

New England housewife by putting into a bed 40 pounds of feathers

according to rule. Besides, nearly all the chairs and especially the

rocking chairs, had large feather cushions in them. It was feathers in

front of us, feathers to the back of us and feathers all around us.

While there was no game in the valley of large size, there was quail, jackrabbit and other small game. Larger such as deer, bear and elk were to be found in the hills and mountains surrounding the valley. Deer were quite plentiful at the head of Dry Creek, south of Roxy Ann. While a little beyond might be found the lordly elk, the black, brown and the dread of the hunter, the grizzly bear. These were frequently killed by the common hunter while the more intrepid brought down the grizzly. My father and others living with the family would saddle their horses in the morning, go to the head of Dry Creek and return at night with enough venison to last the family several days. The hides taken from the deer, elk and other game adorned the backs and bottoms of our chairs, while a homemade lounge was covered with hides taken from different animals. Feathers and hides were always in evidence. The valley being open to all, our stock ran out upon the common. The grass was good, and being of the bunch species, afforded abundant forage for stock in the summer while later in the season its seeds kept the flesh upon them, which the tender grass of the spring gave them. Our work being done by oxen, and no hay to feed them, they would be turned out on the commons at night to be hunted up in the morning which would require the aid of horses, especially if the morning was foggy, which sometimes it was. With horses running at large over the prairie and among the knolls of the valley, when we wished to ride any distance it was necessary to hunt them up, drive them to the corral, catch one and ride to the point we wished to reach. Being the youngest and the "Friday" in the family, it generally fell to my lot to do the finding and driving of the horses home. Sometimes when myself or others would wish to ride to Phoenix, a distance of two miles, I would not return with them until late in the afternoon, when I would find the party who wanted a horse had walked to and from the village, and if I was going, did not go that day, but nursed the wroth of a boy late into the night. The sun would often go down upon one boy's head, in wroth, who had trudged all day after a band of cayuse horses, without finding them. (To

be continued.)

Rogue

River Fruit Grower, June 1911 The Hoxie story will be

continued when and if I find subsequent issues of the Fruit

Grower.IMPRESSIONS AND OBSERVATIONS

In a recent article I spoke of an old-time friend of mine, General W.

H. Byars, whose half-brother, Benton Mires, I recently visited at

Drain. As my wife and I drove at 30 miles an hour over the smooth and

ribbon-like highway along Cow Creek Canyon I could not help thinking of

what Mr. Byars told me many years ago of his experiences while carrying

mail through the canyon in the days when Oregon was still a territory.

I am going to write, in somewhat condensed form, the story of his early

experiences as a mail carrier in Southern Oregon.OF THE JOURNAL MAN By Fred Lockley "The Oakland post office in 1856," said Mr. Byars, "was located on the high prairie, three miles north of the present town of Oakland. Rev. Tower was postmaster, and the post office was in his house, which consisted of two rooms. The first room served as the kitchen, dining room, parlor, living room, study and bedroom, and the other room was given over to Uncle Sam for a post office. "Oakland in 1856 was the terminus of four mail routes. One went to Scottsburg and the mouth of the Umpqua; one via Yoncalla to Corvallis; one by way of the Coast Fork to Eugene City; the fourth via Winchester and Roseburg to Yreka, Cal. At that time the schedule called for a once-a-week service, and the mail carrier on each route had a riding horse and led or drove a pack horse on which the mail was carried. "The mail was made up and dispatched from Oakland every Friday between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. The mail was dumped in the center of the room and each of the four mail routes had a corner of the room to itself. The postmaster, his family, the four mail carriers and any nearby neighbors who happened in would surround the pile of mail and throw the letters and papers into the proper corner, for in those days everyone knew everyone else. When all the mail was worked, the four mail carriers would bring up their pack horses, pack the mail securely, and start on their trips. "I carried the mail from Oakland to Yreka, Cal. Judge James Walton, later a resident of Salem, was the postmaster at Winchester, my first stopping place. He was also justice of the peace and proprietor of the Winchester hotel. The post office was in the bar room of the hotel. Because Wilbur was only three miles from Winchester it was not allowed to have a post office, for at that time no post office could be located within five miles of another post office. Captain William Martin's donation land claim was the first place I passed. The first Masonic lodge organized in the valley met at his home. On the evenings the lodge met the family had to stay overnight with the nearest neighbor. Next on the right-hand side of the trail was the home of General Joseph Lane. Roseburg was the largest and most important place on my route. At that time Richard H. Dearborn, later postmaster at Salem, was postmaster at Roseburg. Sam Gordon, his deputy, took care of the mail. Mr. Dearborn ran a general merchandise store in a one-story frame building. Aaron Rose, proprietor of the town site of Roseburg, ran the hotel, and Dr. Hamilton had a drug store in a small frame building. Judge Matthew P. Deady had a law office there, as did also A. C. Gibbs and S. F. Chadwick, both of whom later served as governor of Oregon. W. R. Willis was justice of the peace and was reading law at the time I was a mail carrier. At this time the land office was at Winchester, but it was later moved to Roseburg. I usually saw Smith Kearney on the street, and also John Kelly, who had a place south of town. The bridge across Deer Creek on Main Street was washed away by the high water of 1857, so I either forded or swam the creek till they put a bridge across Deer Creek on Jackson Street the following summer. "The next post office I served was Round Prairie, and James Burnett was postmaster. The road crossed the Roberts hill a mile to the cast of the present road. The road was changed to a line a mile to westward in 1858 by Captain Joe Hooker, the same Joe Hooker who was later a distinguished general in the Civil War. Captain Hooker had charge of building a road to Scottsburg, and also of the building of the Camp Stewart military road. Six miles south of Round Prairie I passed the Lazarus Wright ranch, on which the city of Myrtle Creek was later built. Mr. Wright kept a wayside hotel. He was a great hunter and kept the post office as an accommodation to the neighbors. I dumped the mail into a box in his house, and the neighbors came in and sorted it over for themselves. I crossed Myrtle Creek on a wooden bridge, which was washed away in 1861. To reach Canyonville, nine miles south of the Wright ranch, I had to swim or ford the South Umpqua River three times. When the river was high I took the trail that crossed a spur of the mountains, thus cutting out two crossings, and made the other crossing on the Yocum ferry. "Ruby Yocum was the belle of that part of the country. Smith Kearney, who drove cattle, was very much smitten with Ruby's charms. Ruby's father had forbidden Ruby to see Kearney, and when he sent letters to her Mr. Yocum destroyed them; so Kearney entrusted his love letters to me and paid me well to deliver them, while Ruby paid me in smiles and thanks. She was always on the watch for my coming. "James G. Clark was postmaster, and the name of the post office was North Canyonville. Aunt Rachel Clark, his wife, was the best cook on my whole route. Jim Clark, the postmaster, ran a combined store, saloon, post office and hotel. Where Canyonville is now located was at that time the campground for freighters, packers, miners and travelers. Just south of the camp ground the road entered the Big Umpqua. I was due at Canyonville Sunday evening, and was always greeted by the settlers for a score of miles around, who came in to help 'sort the mail' and learn the news. After emerging from the canyon of the Big Umpqua the road entered the upper Cow Creek Valley about 10 miles east of Hardy Elliff's house, which was 'forted up' and palisaded as a refuge from hostile Indians. It was usually called Camp Elliff. A. J. Knott originally took up the Elliff place. Knott later moved to Oakland and still later to Portland and became the proprietor of Knott's Stark Street ferry on the Willamette between Portland and East Portland. In 1855, the year before I started carrying the mail, most of the ranch houses between Elliff's and Jacksonville had been burned by the Rogue River Indians and many of the settlers been killed." Oregon Journal, Portland, September 23, 1924, page 8 I have been traveling a good bit of late on Oregon's wonderful roads and have been looking up the history of their location and of the incidents of their early days. As you go from Grants Pass to Jacksonville, you will pass the old-time post office of Galesville. In the early days it was known as Camp Smith, and the post office was kept by Henry Smith. It was stockaded as a protection from the Indians. The Indians attacked it during the Rogue River war. For years you could see the bullets embedded in the logs. Henry Smith was succeeded as postmaster by Ben Sargent, who started a store on the bank of Cow Creek, not far distant. Sargent killed the justice of the peace, and, as there were no witnesses, his explanation that he did it in self-defense was accepted. From the late General W. H. Byars, at one time surveyor general of Oregon, who in his youth carried mail in Southern Oregon, I have had the following incidents of trail life in the early days. "While I was carrying the mail the Galesville post office was moved to the house of Ben Sargent, on the bank of Cow Creek. As there were no bridges across Cow Creek, I had to unload the mail, carry it across on a foot log, swim my horses and repack the mail, at every crossing of the creek. It was six miles over the mountain to Camp Bailey, or the 'Six Bit' house, as it was then called. The first trip I made I ran across the body of an Indian who had just been killed. It was lying beside the trail near where the trail crosses Wolf Creek and near where the hotel now is. "The next post office was at Leland, on Grave Creek. James Twogood, called by the Indians Jimmy Moxclose [a Chinook literal translation of "two" "good"], and McDonough Harkness owned the place at Leland. McDonough Harkness had been killed a few months before, and his brother Sam and family had just moved on the place. James Twogood was postmaster at Leland. There was no other house for 30 miles, so it was a popular stopping place. Leland Creek was not bridged. A log had been felled and smoothed. When the water was swimming deep I coaxed my horses to walk over the log; at other times I forded. I saw a packer leading his horses over the log one day. One of his horses decided to turn around and go back. The horse was loaded with kegs of nails. He had a 400-pound pack, and on turning around on the log he slipped and went to the bottom of a deep hole like a plummet. "South of Grave Creek the road crosses another range of mountains. On the west side of Jump-Off Joe Valley was the Widow Sexton's place. In those days the road turned to the left of the present road and came out not far from where Grants Pass is now located. Abel George had a place on Louse Creek, not far from the Pass. At Evans' ferry was the next post office, though the name of the post office was Gold Hill. There was no settlement above Evans' ferry, north of the river, in 1856. Just across the river from Gold Hill was the Colonel W. G. T'Vault place, and the name of the post office at his place was 'Dardanelles post office.' He moved to Gold Hill to publish the Table Rock Sentinel; so the Dardanelles post office was discontinued. [The Sentinel was published from Jacksonville; the town of Gold Hill didn't exist until 1860 or so. T'Vault, who died in 1869, is not known to have ever lived at Gold Hill.] J. B. White, who lived with Rosenstock, had a mining claim, which he later took up as a homestead. He built a store on his place, and the settlement of Rock Point grew up on his claim after the stage road was changed to the south side of the river. [Rock Point is on the north bank of Rogue River.] Birdseye and Dr. Miller had places on the south side of the river near Gold Hill. The road in those days left The Dardanelles, ran up a small stream for a few miles, crossed a low ridge to Willow Springs, and ran along the south slope of the oak-covered hills to Jacksonville. When I first started carrying mail Mr. Siphers was the postmaster, but soon Judge Hoffman succeeded him. On mail day a big crowd gathered in front of the post office. When the mail was sorted the postmaster stood on a box in front of the post office and read the names on the letters. The men in the crowd were not allowed to force their way through the crowd, on account of the confusion. They answered their names or held up a hand, and their letters were passed back to them from hand to hand. [C. C.] Beekman, later a banker and Wells Fargo agent, had a news stand and also ran an express to Yreka, 60 miles over the mountains. Jacksonville was a wide-open town, and the hills and the banks of the streams were dotted with the cabins of miners. Gassburg, now Phoenix, and Camp Stewart were the only other places on my route to Yreka." These old roads saw comedies as well as tragedies. When Sol Abraham, later a progressive and well-to-do merchant at Roseburg, was carrying a pack, selling goods from door to door through Southern Oregon, he approached one evening the home of Lazarus Wright, on whose homestead the city of Myrtle Creek is now located. He saw in the road a beautiful little black-and-white animal, which seemed quite gentle. He had never seen anything of the kind before, so he decided to catch it and make a pet of it. He stooped over to pick it up, but suddenly changed his mind. A few moments later he came to the Wright house and asked if he could stay overnight. He joined the family circle about the fireplace while waiting for supper to be prepared. Lazarus Wright was a great hunter. He had a pack of hounds, three or four of which were in the room. Mrs. Wright came into the room from the kitchen to announce supper, and instantly seized her broom and chased the hounds out of the house, saying: "These miserable hounds have been killing another skunk." Driving the hounds out of the room did not remedy the matter, for the odor seemed to grow stronger and more offensive. Sol Abraham then confessed to trying to catch the pretty little black-and-white animal in the road. Mr. Wright, who was as tall and slender as Sol Abraham was the reverse, brought out a suit of his clothes for Mr. Abraham and took out his perfumed garments and buried them so that the earth would absorb the odor. Sol Abraham looked like a very small boy in his father's cast-off clothes. During the night the cattle came down from the hills and created considerable disturbance. In the morning Mr. Abraham went out to get his clothing, but he found that the cattle had pawed the earth away and had torn his clothing into shreds and fragments. The nearest place where he could get any more clothes was at Jacksonville, 85 miles away, so he had to continue his journey, peddling his goods, in Mr. Wright's ill-fitting clothes. Fred Lockley, "Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man," Oregon Journal, Portland, September 24, 1924, page 10 IMPRESSIONS AND OBSERVATIONS

You will find the roads of Southern

Oregon redolent of history. Just south of the one-time post office of

Galesville is the ranch formerly owned by the Redfields. When they were

attacked by the Indians Mr. Redfield, who had but one arm, stood the

Indians off until the man with him was killed. He and Mrs. Redfield

then started for Camp Smith. Mrs. Redfield was shot through the knee,

but they succeeded in reaching their destination.OF THE JOURNAL MAN By Fred Lockley Just to the south of the Cow Creek divide, at the foot of the mountain, Holland Bailey of Lane County was ambushed by the Indians. Those with him escaped, for the Indians, hearing a pack train approaching, reloaded their guns and awaited its coming. When the pack train arrived the Indians permitted it to proceed without molesting it, for it was in charge of Jimmy Twogood, who had always been a friend of the Indians and had treated them justly. This was on October 23 [1856]. On the same day the Indians burned most of the settlers' homes in the neighborhood. As you cross the mountain you come to where the old "Six-Bit" House stood, on Wolf Creek. An Indian was caught there by the settlers and was accused of stealing. He denied the accusation, but the settlers concluded that they might not be able to apprehend the guilty party and that a bird in hand was better than two in the bush; so they decided to hang the Indian anyway. The Indian had eaten his dinner at the hotel on Wolf Creek, and the proprietor demanded of the men hanging the Indian that they adjourn proceedings till he collected six bits from the Indian for the dinner he had eaten. When the money was paid the pony was led from under the Indian and he was left at the end of the rope to strangle to death. An Indian boy, who was employed by the owner of a pack train to ride the old bell mare, while passing near the Six-Bit House was shot and killed by a white man, who explained that he "did not like the color of his skin." Not far from Wolf Creek is Hungry Hill. Here it was that a battle between solders and Indians occurred in which 12 white men were killed and 27 wounded. Leland and Grave Creek are mere names to the passing tourist, yet they are reminiscent of early-day tragedies. In 1846, as the emigrants were making their way by the southern route to the Willamette Valley, Martha Leland Crowley died and was buried on the banks of this stream. The grave was carefully concealed, but the Indians found it and opened it to get the clothing. Leland post office and Leland Creek perpetuate the name of this young lady. As you cross the range of mountains just south of Grave Creek there is a little stream to the left of the road. In the winter of 1855 or 1856 a young man was found by the side of the trail. He had apparently given out, and before lying down to die had knocked the hammer from his gun so that the Indians should not use it. His name was never learned, nor was it known where he came from nor where he was going. Just below the place where he was found there used to be a maple tree. The water ran down the hillside, forming a pool under the roots of this old maple. In the winter of 1858 a young man of about 30 was found drowned in this pool. He had long and curly red hair. He was on his way from California on horseback to buy cattle in Oregon. Who he was and whether he was killed for his money, or how he came to his death, was never learned. Beyond this the old road ran in front of the Harris place. George W. Harris, with his family, had come from Damascus, in Clackamas County, a short time before and had taken up a place there. On October 9, 1855, some Indians came to his place and when, at their summons, he came to the door, they shot him through the breast. As he lay dying, he told his wife to load the guns and to stand the Indians off. Mrs. Harris had a little girl. She barred the door and used her gun to such good effect that she was able to keep the Indians away until dusk. Then, with her little girl, she stole out into a thicket of nearby willows and escaped. Her little boy, who had been sent on an errand to a neighbor's, was never heard of afterwards. A nearby settler, named Wagner, was away from home that day, as he had been hired to take a lady who was lecturing on temperance to some mining camps in Josephine County. His wife and baby girl were left at home. His home was burned, and he never learned the fate of his wife or child. An Indian long afterward said she had barred the door and set fire to her house, and as the flames crackled they heard her sing. But other Indians said she and the little girl were taken prisoners and the baby was killed because it cried too much, while the mother refused to eat, and died of starvation. The Indians never attacked travelers in what was known as Big Canyon. In the days when the Hudson's Bay travelers roamed all over the country a party of trappers were camped on the Umpqua River, just [north] of where Canyonville was later built. Some Indians stole their horses and secreted them in a small prairie nearby. The trappers, being expert trailers, followed the trail and divided into two parties. They attacked the Indians at daylight from opposite directions, being both above and below them on the trail. They killed all of the Indians and recovered their horses. Not an Indian escaped, and the other Indians finally started out to look them up. They found their bodies, but were never able to discover how they came to their death. The Indians thought they had been killed by the Great Spirit, and, although huckleberries grow in profusion in this canyon, the Indians would never gather them. They always look for a trail over the mountains rather than pass through the canyon. In the late '50s a new grade was made through the canyon. Shortly after it was made a four-horse team was driven over the new grade. The earth gave way, and driver, wagon, and all four horses rolled down the mountainside into the stream, the driver and all four horses being killed. Oregon Journal, Portland, September 26, 1924, page 8 Diary 79 Years Old Yields Strange History:

Arthur Fenner married Emma Floed, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. J. C. Floed

of Roseburg. J. C. Floed was for years in pioneer days Roseburg's

leading merchant. Mrs. Floed was a daughter of General Joseph Lane,

Marion of the Mexican War, first territorial governor of Oregon, etc.,

etc.Journey to Oregon in 1856: Mrs. Fenner was therefore a granddaughter of General Lane. Arthur Fenner was a resident of Salem some time in the seventies, for about two years, when he had a store here. Afterward, for a long time, he had a confectionery and cigar store in Roseburg, and later the Arthur Fenners went to Denver. This information leads back to a remarkable diary of a journey from New York to Oregon in 1856, kept by Arthur Fenner's father. The Bits* man has copied in full this diary, and it will appear in this column, commencing with this issue. The boy Arthur mentioned in the diary is Arthur Fenner, who married Miss Floed, granddaughter of General Lane. After finishing the printing of the remarkable old diary, now for the first time being put into type, there will follow some explanations--showing by unmistakable incidents the historic accuracy of all that Arthur Fenner's father laboriously wrote in longhand while on his journey to Oregon. It was before the day of typewriters. The hand is clear, Spencerian--and the reader will agree that it is the work of a cultured gentleman. The writer has the impression that the long journey to Oregon by the father and mother of Arthur Fenner, with their two small children, was made with no intention of remaining--but merely that Mrs. Fenner might visit her brother, who was A. R. Flint, then of Roseburg. The pioneer Flint home was at Winchester, first county seat of Douglas County, A. R. Flint having come from San Francisco in 1850 to survey the townsite of Winchester, and, liking the country, returned for his family. He was chosen the first county clerk of Douglas County, which was created by the territorial legislature meeting in basement rooms of the Oregon Institute building for its first term there, 1851-2 session: the Oregon Institute being chartered at the following session in the same rooms as Willamette University. Mr. Flint was reelected county clerk at the following election, and, soon, the county seat was moved to Roseburg. But the visit of the Fenners resulted in their son Arthur becoming a resident of Oregon. With the above introductory words, reserving further explanatory remarks for the concluding issues, the old diary reads: "We left New York April 5th, 1856, per steamship Illinois at 2 p.m. in good spirits and favoring breezes, for the far-off West. (April 5th that year was Saturday.) Nothing occurred to mar the pleasures of the day until Tuesday night, when we experienced a severe gale accompanied with heavy thunder showers. There was very little sleep that night, and the empty seats at table in the morning made us aware of the fact that provisions were rising instead of falling, and that a repetition of such scenes would not only give the owners a handsome figure, on the credit side, but make the doctor smile all over, as he dispensed his powders and pocketed his fees. However, as time heals all things, so our fellow passengers were allowed the privilege of dispensing with the powders and retaining the fees, also of partaking of the more solid condiments--and, by the vigor of their attack upon the good things spread before us showed that that vacuum abhorred by nature would soon be a state of plethoric fullness, and that the short respite allowed them by the antics of old father Neptune, in kicking up such a dust, was but a prelude to the glorious scenes that followed; and the repeated calls for roast beef, turkey and chicken fixin's affirmed the truth of the old saying, to the groaning and perspiring darkies, that 'there is no rest for the weary.' "Tuesday we were alone upon the waters, with the blue above and the blue below. Thursday we made the Florida Keys. We could see the white beach in the distance, and the surf roll up and break on the shore. On the farthest point lay the hull of a large ship, wrecked a short time since. It loomed up grandly in the distance. We passed on, speculating upon the probable fate of those who once peopled her decks with busy life, and guided her over the pathless deep. "On Friday at 12 m., we made the green isle of Cuba, with its hills and dales basking in the golden sunlight, while here and there a white cottage peeped out from amid the foliage. We sailed along its shores for some two hours, and about 2 p.m. entered the mouth of the harbor. On the left stood the frowning walls of Morro Castle, on its rocky bed, firm as adamant, its base washed by the waves of old ocean, while on our right lay the city of Havana, with its ancient sea walls and defenses. We had a fine view of the city as we sailed up to our anchorage on the opposite side of the bay. We could see the volantes (two-wheeled carriages) as they passed along the streets, drawn by mules, accompanied with outriders and footmen. The body of the carriage was set between the wheels very low, especially for lazy persons, I presume." *R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 9, 1935, page 4 "The houses (of the Havana of 1856) are mostly of one story and covered with tiles. The harbor is in the form of a circle and surrounded by hills that rise gradually up from the shore, with cottages and neat gardens enclosed; shaded by the cocoa, the palm and the orange trees, they looked the picture of contentment. "Soon as we dropped anchor we were visited by the custom house officers, health officers, and, lastly, by the captain general and his suite. He was a fine, portly-looking man; looked as though he and the world were on the best terms possible. After going through the preliminaries of a visit, he took the captain and his ladies on shore with him. "After they left we were visited by bumboats, as they are termed, filled with oranges, pineapples, cigars and jellies. The officers would not allow them on the vessel for fear of creating sickness, but some of the passengers managed to smuggle a few on board by means of baskets attached to a rope. "We were compelled to remain all night, as no vessel is allowed to leave between sunset and sunrise. But it gave us an opportunity to see the sun rise over the hills and bathe the city and harbor in a flood of golden light. 'There were some 50 vessels in the bay with sails all set on the eve of departure for their far-off homes, and the jolly heave-ho of the sailors as they hoisted the anchors, mingled with the song and the jest, came floating to us on the balmy breath of the morning. It spoke of light and merry hearts enlivened with the hopes of a speedy reunion with friends at home--while our courses were set for the land of the stranger. "There are no wharves at Havana. Vessels are obliged to lay off in the bay; they are loaded and unloaded by means of lighters. It is very expensive and laborious. The shore is very bold in many places, and ships of the largest class can haul close to the shore without any difficulty. "The natives are about 50 years behind the age. A little Yankee genius and enterprise would develop things amazingly here. "We weighed anchor about 8 a.m. and sped on our way, with gentle breezes and a calm sea. On the second day out, Arthur was taken down with a light fever, which kept him down about a week. "Tuesday morning about 9 a.m. we reached Aspinwall in the midst of showers, went on shore and took shelter at the Ocean House, the hotel here. It resembles some decent barns I have seen at the north. "Sat down to a decent dinner about 1 p.m., and at 1:30 took the cars for that interesting country, Panama. 'Had a very pleasant ride over. The road on each side was lined with groves of palm trees. The rains had laid the dust. We were also provided with cool breezes; they were very acceptable. "We arrived at Panama about 4:30 p.m., and, learning that the steamer would not sail that night, we went up to the city and took quarters at the American hotel. "After partaking of a lunch, I went back to the station to have my tickets registered, and my state room assigned me, so as to be ready to go on board in the morning. "Found a large number of passengers there; concluded to await my turn with the rest, when we heard the report of a pistol, and soon after the cry, 'An American has been shot!' "Immediately all was excitement, a rush was made by the passengers--many for the scene of action, some to the hotels, where their families were; others to the ferry boats. "I took my station in the freight room door, where I witnessed all that transpired on the outside. Saw a native run up among the negro huts, pursued by an American, followed by the report of a pistol. "Soon after the latter returned and all was quiet for a few minutes; but the flame was only smothered a little, not extinguished. "In a few moments a large crowd of natives came rushing down from the cienega (swamp) with their passions all aroused, exclaiming that one of their number had been shot by an American, and they must have revenge, and with the cry, 'Cavaho Americano!' [probably "carajo"] they made a rush for the Triangle, a small drinking saloon kept by an American. "This was soon sacked, amid the yells of the natives, the crash of glass, and the reports of pistols. ''From this they proceeded to the hotels and stores, which they served in a like manner, robbing the occupants and demolishing everything that came in their way, also partaking freely of the liquors, which fitted them for the scenes that soon followed. "A large number of them collected outside of the cienega, and commenced firing upon the depot, and among the passengers on the outside. ''During this the bells of the different churches of the city were ringing the alarm of fire, the houses of all the foreign residents were closed and barred, and confusion and dismay held reign over all.'' R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 10, 1935, page 4 "But hope revived as we heard the bugle of the police in the distance; but that hope proved delusive, for instead of quelling the riot and dispersing the mob they joined in with it, and, forming into a column, they marched on and surrounded the depot, and commenced firing into the doors and windows that were open. "One side of the freight room was packed with men, women and children. Prayers of man to his Creator for forgiveness of his sins, the wails and anguish of woman as a fate more horrible than that of death rose before her excited vision, the screams of helpless children--the scene was truly heart-rending. "I made out to close the large doors, so as to shield them as much as possible from the storm of bullets that came pouring in, one of which struck me in the right shoulder, causing a small indentation. "I returned to my station in the door. The side of the building where I stood was some 10 feet above the level, the ground on that side descending. I had been there but a few moments when a passenger accosted me. I turned to answer him. At the same moment a ball struck me in the back of the head, stunning me for a few moments. I soon recovered, turned about and looked down. "An old Jamaican shook his pistol at me, exclaiming at the same time, 'I had you dere!' The blood from the wound aroused me, as it ran down my back. "My choice was soon made. There we were at the mercy of an infuriated and brutal mob, with no hope of escape, and no arms but those which God and nature gave us for our defense. It was fight to the death or fold your arms and be shot down like dogs. "I chose the former, and with that determination entered the ticket office, the first scene of attack; saw but one man on his feet. He was bracing against one of the doors, to keep it closed. Under the counter were piled men two and three deep. "I went to work with such weapons as I could find, and kept one window clear for a few minutes, soon after receiving five balls in the back, one of which entered near the spine, passing through the lungs and coming out near the left nipple. The other four were spent balls, and remained in my clothing. "I fell forward on my hands and knees, and crawled back into the freight room; arose on my feet and made out to stagger to the farther end of the room, the blood pouring in streams from my wounds. "I fell forward upon a pile of baggage, and was lost for a time; I was at home, but dreaming about crossing 'the isthmus' and being engaged in a 'riot,' also mortally wounded. "I soon recovered and found it was not all a dream, but a sad reality. "I looked about me and found a case standing outside of the room, about four feet high and three feet wide, and laid down as comfortably as I could, with one knee braced against an upright post; thought I would improve all the chances that offered, although they were doubtful. "It saved me from being trampled upon by the mob. Had hardly accomplished this when the doors were burst open and the mob came pouring in, with their savage yells and wild music; this mingled with the discharge of muskets and pistols, the clashing of knives and machetes, the cries of helpless women and children, the petitions of men for mercy. "'Take all we have, but spare our lives!' "'No! cavaho Americano!' (death to the Americans) was the cry, and the slaughter went on. "'May I never witness another such scene; it seemed as though all the demons of hades had risen to glut their orgies in blood and death. "After a while the carnage ceased, caused by the arrival of the governor, the chief of police, several priests and a deputation of Panamans [sic]. They succeeded in dispersing a large portion of the mob, but some remained to plunder. "I closed my eyes and shut my teeth firmly together, at this juncture; determined to bear all their inflictions, rather than expose myself, or ask a favor. "There were as many as 30 different parties engaged in robbing and examining me. Only three of them gained the spoils. It was a trying ordeal, but I went through it bravely. "They worked about me, it seemed, for hours. Among the baggage, crash went the axes and hatchets into trunks and valises. Nothing escaped them. "The last party that robbed me consisted of four or five. They examined me very closely, every nook and corner. At last they discovered my belt. Their knives were at work in a moment. After cutting it, they pulled it off with a force that nearly carried me with it. "After dividing it, they commenced cutting into the case, saying, 'burn him, burn him'; but finding they could not arouse the sleeping 'possum, they desisted, and commenced rubbing my arm, tried my pulse, smoked in my face, pinched me, pulled my eye winkers--and, as a finishing stroke, plunged a knife twice into my side, exclaiming, "'Kill dam Yankee!' 'dam Yankee dead!' they then went as far as the door, but returned and gave me one more look, muttering 'sure gone,' then took their final leave. "Was very glad to part company with them. After they left I was lost to myself, or had partially fainted. Recovering after a while, all was quiet and still around me." R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 11, 1935, page 4 "I ventured to open my eyes. All was darkness. The window near me had been burst open, and the damp air coming in upon me had chilled my whole frame. I could not move, while within all was a raging fever. "Soon after I heard voices near, and I closed my eyes once more. They approached me, talking of the rack and the thumbscrew. Thinks I, what is coming next? "They took me down with no gentle hand, and carried me out. I felt the cool breeze play over me, and heard the waves roll up on the shore. Will it be a watery grave? "No; they passed on, descended a few steps and laid me down on a hard floor, with my head on a pillow. "Heard voices talking eagerly in Spanish. Soon it changed and the English came to my ears with a refreshing sound. I soon recognized the voice of Dr. Otis of the Illinois; opened my eyes and made myself known to him. "One of the physicians came and looked at me, and said, 'You are doing well.' Some days after that he told me he thought I was in a dying state, and, from the nature of my wounds, no hope. "There were eight of them in that room, some of them mortally wounded. The physician soon left us, in the charge of four natives. "We kept them busy the balance of the night passing us ice water. They had to feed it to us in spoons; we were unable to drink. I was shaking with the chills nearly the whole time--at the same time filled with a burning thirst. "I lay there until the next morning about 10 a.m., when a young Panaman came in, accompanied by a number of priests. He inquired my name and circumstances. I informed him, also that my family were at the American hotel, ignorant of my fate. "He went directly up and informed them, and soon after returned, with a cot bed and four men, and conveyed me up to the hotel. After a while the physician came, dressed my wounds and made me as comfortable as possible under the circumstances; bathed me in ice water and ordered it for my drink--the only thing that passed my lips for four days. "The room that we occupied was very close, and the air oppressive. This did not suit our physicians, so on the third day we were removed to a pleasanter part of the city. They had procured two large, airy rooms, one of which we occupied; the other by the Rev. Mr. Sellwood and Thomas Bland. "They also employed a man to take charge of us. He remained with us during our stay. The house in which were our rooms had formerly been occupied as a hotel, and contained some 20 families, all of them friendly to us but one. "They visited us daily, bringing the different varieties of fruit peculiar to that clime. "There was one family in particular that visited us, an elderly lady and her three daughters. They came morning and evening bringing us fruits, flowers and sweet-scented shrubs. They would sing to us and accompany it with the guitar, their old Spanish songs. "Owing to our limited knowledge of the Spanish, we could not converse with them, except through an interpreter; Captain Ferguson, our right-hand man, acting as such. "On the fourth day, Alice was taken down with the measles and Panama fever. She was very sick with them. Such diseases are often fatal with children in that climate. Many of those who visited us expressed surprise at her recovery. "Arthur had the measles in a light form. "After a while we were allowed to eat oranges. Rev. Mr. Rowell, a daily visitor, would bring them to us, picked fresh from the trees. They were delicious. "Col. Rostrup was another daily visitor. He brought us books and papers to read, and wine for the inner man. He also furnished us with a hammock and rocking chair. He was a generous and noble-hearted man. "Mr. Strahan, another of our visitors, was very kind to us. He made the children golden presents. "We had kind and attentive physicians. Everything that could add to our comfort or happiness was furnished us; we had but to express the wish to find it gratified. "The houses are built of stone, and surrounded with balconies. The partitions are formed of rough boards, and are whitewashed. There are no chimneys or fireplaces. The poorer classes cook their food by means of furnaces, using charcoal. Their bread is all obtained at the bakery, and is very good when fresh from the oven. "The wealthy classes receive their meals from the restaurants. They have coffee at 7, breakfast at 10 a.m., dinner at 5 p.m., and tea in the evening. "They are all inveterate smokers, from the sleek, well-fed priest down to the ragged urchin of 5 years; both sexes and all classes. The cigar is ever their constant companion. "We had a fine view of the market place from our balcony. It resembled a beehive during trading hours. They commence at 4 and close at 10 in the morning.'' R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 12, 1935, page 4 "Here are exposed for sale the products of the country--milk, eggs, beef, venison, bananas, plantains, mangoes, alligator pears, clams, oysters, tortillas, charcoal, breadfruit, pineapples, coconuts, oranges and fish. They have excellent fish in the bay, but it is difficult to obtain them. The natives will not fish much, unless driven to it by necessity. "Panama is a city of churches. Many of them, however, are in a state of decay. The cathedral is a fine-looking building. The outside has some pretension to beauty and order. It fronts on the plaza. The churches are built of rough stone, without order or regularity. The exterior presents but little attraction. The interiors of some of them are highly finished and possess many valuable paintings. "There was one directly opposite our rooms, its side fronting us. There were two large doors in this side, and, when opened for services in the evening, we had a fine view of the altar and the shrine of the virgin. Before this were ranged eight large candles, all burning; before stood the priest with different-colored robes on. He would read a few sentences, make a curtsy, throw off a robe, and then repeat the same ceremony. "On his right stood a subpriest or deacon, holding in his hand a vessel containing liquid in a burning state. We could see the vapor arise from it as he swung it to and fro, while the priest was repeating his Latin phrases. This was the incense, probably, that they offer to the shrine of the virgin. "On the right of the priest stood a boy holding a lighted lamp, probably to throw some light on the subject. "After this ceremony closed commenced the chanting.… The audience, when they went in, would kneel, making the sign of the cross, then seat themselves on the floor, and remain there until the services were closed. "In the belfry were four openings, each containing a bell. Two of them were struck by means of ropes attached to the end of the clapper; the other they beat upon with pieces of iron, creating a most horrid din. "The last eight days of our stay they held services each day. Their chimes were kept up for an hour at a time. It seemed as though the little darkies delighted in stirring up the nervous system and producing a second bedlam. "We had a fine view from our rooms. On our right lay the bay, dotted here and there with green islands. On our left was the open country, hills upon hills, mountains upon mountains, crowned with the cocoa, the palm and orange trees, with their carpets of green interspersed with beautiful flowers, and sweet-scented shrubs. "Nature glowed in all its luxuriance. Strange that so lovely a land should be the abode of ignorance and superstition. "We bade adieu to Panama and our kind friends on Saturday, May 17th, after a confinement of 30 days--friends whose kindness and sympathy manifested to us during our illness merit our gratitude, and they will ever hold a place in our remembrance. "Captain McLane, agent of the steamship company, and his lady; Rev. Mr. Rowell and lady, Col. Ward, U.S. consul; Messrs. Rostrup, Codwine and Strahan, Captains Childs and Ferguson, and, last, but not least, our kind and worthy physicians, Senors Emilio Le Breton and Jose Keratochuil. "About 5 p.m., the cars arrived with the passengers from Aspinwall, and about 9 p.m. our parting gun was fired, and we were once more on our way to the promised land. "The Sonora is a fine boat, well ventilated. Captain Whiting is a perfect gentleman, but as to the other officers I have but little to say in their favor. Their own personal gratification was paramount to all the comfort and convenience of the passengers, with the exception of a few of the 'fancy,' to whom they were all attention. "The first few days we passed along very well, but soon Allie's appetite began to fail, her food did not relish well, her strength soon left her; the doctor would order drinks and food to be prepared for her, but it was difficult to obtain them, unless you paid EXTRA, and that the state of our funds would not admit of. I think the company ought to pay their servants well, instead of compelling the passengers to PURCHASE those attentions that belong to them of right. "Fortunately, though unexpectedly, Allie lived through it all, and after an otherwise pleasant trip of 14 days we arrived at San Francisco Sunday morning, June 1st, about 9 a.m., took up our abode at Hillman's Temperance House, where we enjoyed all the comforts and quiet of home, and received many tokens of kindness from the proprietors, Messrs. Smith and George, also from their worthy landlady, Mrs. Lambert. "We also found many kind friends among the boarders, whose sympathy for our misfortunes, and whose many little acts and tokens of kindness, though they may appear as trifling, still in the aggregate form quite an important item on the side of gratitude. "With good, wholesome food and attention, Alice soon changed, and a few days of quiet had a marked effect upon her, and during our stay of three weeks she gained steadily. "Dr. J. J. Cushing, formerly of Providence, attended her, and took a great interest in her recovery. His services were gratuitous. To him also are we indebted for many favors. "We arrived at San Francisco in the midst of exciting times. Murders and robberies were of daily occurrence; rowdies and blackguards controlled the elections, usurped the places of trust and power, interpreted the laws to suit their own peculiar cases, and ordered the people's money into their own pockets." R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 13, 1935, page 4 "These persons had ranged themselves under title of the 'law and order party.' (A skunk by another name would emit the same odor. Comparisons are odorous, as Mother Partington informs us in her diary.) "Opposed to these means the vigilance committees, composed of nine-tenths of the citizens, including all the better portion, men of all parties, who combined together for the public good; men who had borne their grievances for years, but who determined upon the complete and thorough purification of the moral and political welfare of the city and county--they were considered competent for the task, and events as they have transpired go to show that the task, however arduous and trying, has been faithfully accomplished. "No danger could appall or threats deter them from performing their duty. They were ready on every occasion to 'face the music.' "Monday, June 2, called on Mr. Robert S. Knight. Received the right hand of fellowship for 'auld acquaintance.' He kindly intimated that there would be no trouble in our being put through to our destination; that I need have no fear on the score of funds, and, in company with him, called upon Moses B. Almy, another Rhode Island boy. Found him well situated and in the enjoyment of good health. "Received friendly assurances from him. Spent a portion of the time rambling about the city. Saw all the lions; the elephant had stepped out. "Was presented with a ticket to the reading room for one month by Dr. Cushing. Had the pleasure of perusing the Rhode Island County Journal, also the various papers and magazines from the different states. "Saturday, June 21st, we took passage on board the propeller Newport, bound for the Umpqua. "Expected to sail in the evening; but the alarm bell of the committee (vigilance committee) commenced ringing soon after; Captain Johns and the principal officers took leg bail [i.e., "ran"] for the scene of action, which resulted in the stalling of Hopkins and the arrest of Judge Terry. (Explanation later on.) "Sunday morning, we took our departure. All seemed to go well until we were outside. Passed a very rough night, awoke early in the morning, and found we were nearing the city. Inquired the cause, and learned the engineer and fireman were seasick! "Remained in port until Thursday morning. After receiving a new complement of hands, we took our final departure. The day passed off very well. On the second day there seemed to be some defect in the machinery, the steamer making but little progress. "We ran back a few miles for a harbor, and entered the bay of Tobaga (likely Bodega); remained one day, repaired the boilers; the next morning we headed once more for the north; but, unfortunately, our stock of coal gave out, and we were obliged to run inshore and cut our fuel. Remained two days, took on board a large quantity of green wood, not very admirable for steaming purposes. "However, with the aid of favorable breezes, we were enabled to reach Trinidad, remaining there two days to 'wood up.' Went on shore, gathered a few berries, and took a view of the 'city.' It is pleasantly situated, upon a high bluff, and commands a fine prospect. "On Friday at 6 p.m. we up anchor for Crescent City, a distance of 50 miles, which we were enabled to reach about noon on Saturday--after consuming all our wood, and all the dry lumber the vessel affords. "Remained three days to 'wood up.' Went on shore and took a look at the city. It lays somewhat low, a few feet distant from high-water mark, and in a southeast storm the sea runs up and washes the buildings. "They have a fine, hard beach some three miles in length in the form of a crescent. It forms a beautiful drive, and on Sunday it was covered with saddle and carriage horses. "Visited the Indian burial grounds; saw one grave of recent construction. There were two sticks at the head and foot, with a cross stick. On this was hung a coon skin, several ears of corn, and a few strings of beads, while on each side of the grave were ranged three baskets inverted. They probably contained food to sustain them on their way to the happy hunting grounds provided for them by the Great Spirit. "Tuesday night about 12 m. we set our course once more; had been out but a few hours when it commenced blowing a gale, which lasted 48 hours. The first night there was no sleeping. The heavy seas would strike the sides of the vessel, making everything shake; the sofa and chairs danced from one side of the room to the other; there was little chance for eating; we had to hold our hair on with one hand and the plates with the other, while the tempting dishes seemed to laugh in our faces, and say, come, eat us--while the salt water came dripping down through every crack and crevice, turning the old ark into a complete watering pot, and, as we had no dove to send forth for the olive, we concluded to head our vessel for a second Ararat-- "And, Thursday about noon, we altered our course and ran for land, and at 6 p.m. we entered the harbor of Trinidad once more; were very thankful to enjoy a little calm once more. Remained this time three days; 'wooded up' once more, and, on Monday morning hoisted anchor and set our course for Crescent City. "The gale having subsided, we sailed on with gentle breezes and a calm sea, and, on Tuesday evening, we entered Coos Bay; anchored off the city about 6 p.m. "The city presented quite a respectable appearance. There were a few decent houses, a hotel and a stockade fort. There are no churches in these 'cities,' and very little if any society. They are merely trading posts, for supplying the interior miners and hunters with provisions. R. J. Hendricks, "Bits for Breakfast," Statesman Journal, Salem, July 14, 1935, page 4 "John, the celebrated fighter, with about 150 of his warriors, were crossing the bay at the time on their way to the reservation, under the guidance of Uncle Sam's boys. "We remained there until morning, then up anchor and ran up the bay some four miles to take in coal, which occupied us two days. It was a wild spot, and surrounded by forests. "We spent most of the time on shore, gathering berries and rambling through the woods. "There was one log house on the shore, which we visited; found it alone and deserted. The sign still remained, 'Marshfield House, Meals at all hours of the day.' "We entered the kitchen, found a few empty bottles, shook them up, but no friendly chipper greeted the ear. Their glory had all departed. Here once the fumes of bear meat, venison and elk steaks, and their invaluable accompaniment, 'Old Bourbon whiskey,' greeted the nasal organs of the weary hunter and miner. With a parting sigh to the bottles, we passed on to the boat--and washed down our regrets with a copious draught of PURE MOUNTAIN WATER, in which Oregon abounds. "Friday morning we took an early start for Umpqua City, which we reached about 2 p.m., came to anchor and discharged cargo. "Soon after, the canoes began to put off from the shore; a large deputation of Indians came on board to inspect our vessel and cargo. "Sallie was much frightened at their appearance, and wished the captain to turn about and go back, but they were harmless, their visit being a friendly one. "The cook purchased a bushel of fish from them, for six small biscuits and some old salt junk. We had a feast on them while they lasted. "The city contains one decent house, three shanties, and some 50 Indian huts. "Saturday morning we went on board the little steamer Excelsior, bound for Scottsburg, 26 miles distant. Sailed about 10 a. m,, passed the FLOURISHING cities of Gardiner and Providence, each containing one house, a barn and a pig pen. "The river is narrow and very crooked, and the mountains rise abruptly from the shore, on each side, to the distance of several hundred feet. "We had a pleasant sail up, and arrived at our destination about 2:30 p.m. Took quarters at the Scottsburg House, and soon after sat down to a substantial dinner of bear meat, new potatoes, fresh bread, butter, pies and cake. "It was quite a change from our ship fare, and we did justice to the occasion. "Found some very pleasant families here. The city stands upon a narrow level, about an eighth of a mile in width and three-quarters of a mile in length; contains some 20 buildings, hotel, stores and dwellings. "It was quite a trading post a few years since, and large quantities of goods were packed here for the mines--but since that the trade has been directed to the interior, and Deer Creek, Winchester and Jacksonville contest for the spoils. (Deer Creek was the original name of Roseburg.) "Remained here four days. Wednesday evening Mr. Flint arrived with horses for our convenience. "Thursday morning we bade our kind friends goodbye and took our departure for the promised land. Found the first few miles of travel rather tiresome, but soon got accustomed to it. "The hills, mountains and prairies tried Sallie's nerves severely. "After traveling some 20 miles, we took shelter with a Mr. Kellogg for the night; sat down to a good substantial supper about 8 p.m., and soon after retired.… After breakfast we mounted our horses with weary limbs. "Mr. Kellogg very considerately made no charge for our stay.… His family consisted of wife, two daughters and four hired men.… We made them a kind good morning and rode on. "After a ride of some three or four miles, we halted at a small creek in the woods, to take rest and a little refreshments. Remained about an hour, then mounted once more and proceeded on. "Took a lunch with Mr. Stevens, and about 5 p.m. arrived at Collins Place. Our ride was pleasant but tedious--it being some 20 years since we had mounted a horse. However, we accomplished the journey without accidents, or being taken by the Indians; very much to Sallie's regret, I presume." ----