|

|

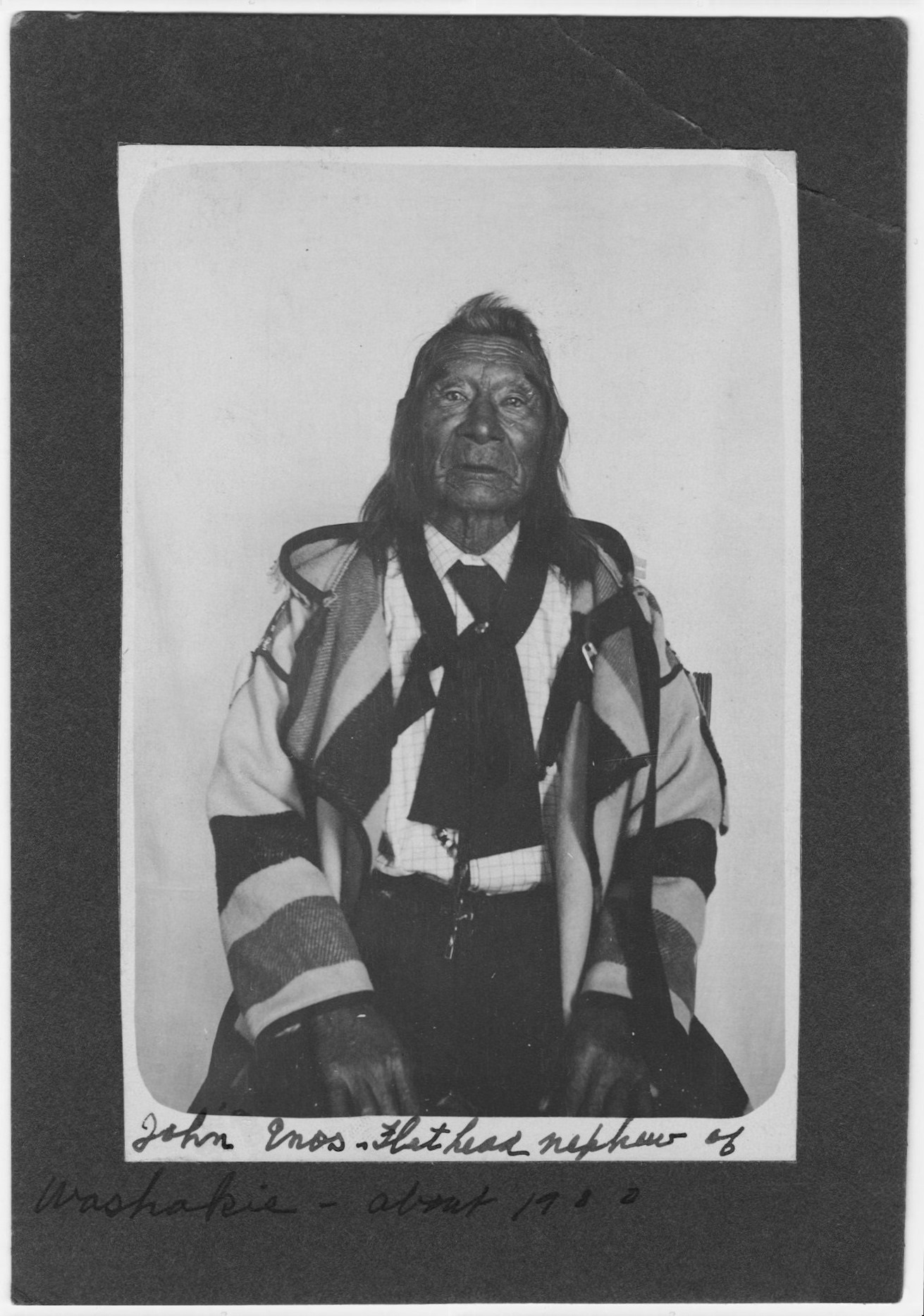

Enos These Enoses couldn't have all been the same person--though they claimed to be. You figure it out. Click here for the current version of this page.  John

Enos of the Wind River

Reservation,

circa 1900

When [Benjamin] Bonneville arrived at Green River in the fall of 1832,

pulling twenty loaded wagons, it was believed that his mission was to

prove that wagons could be taken across the divide at South Pass. . . .

On these wanderings, he picked up the 10-year-old Enos--nephew to Gourd

Rattler--as a guide. [Page 360]

Gourd Rattler (known to the Americans as Washa'kie) . . . [was] one of the important head chiefs of the Shoshoni nation. [Page 9] Gale Ontko, Thunder Over the Ochoco, vol. I, 1993 Up in the Blue Mountains [in 1843], Enos--20-year-old Snake warrior, former scout for Bonneville's undercover mission and one well acquainted with the Ochoco--bid his disgusted Shoshoni relatives farewell and rode south in search of Fremont to offer his services as a guide. John Enos--his baptismal name bestowed by Father de Smet--was a nephew to both Gourd Rattler and Iron Wristbands. [Page 15] Because of his blood ties to the hostile Snake war chiefs, John Enos was discharged [by Fremont] at the Dalles. [Page 18] King John--Tehastas--head chief of the Rogues, who had been involved in minor conflicts with American settlers since 1851, watched troop movements into southern Oregon with bitter uncertainty, knowing his people were the next military objective. With this in mind, King John engaged the services of the Snake warrior Enos to stir up hatreds among the tribes of southern Oregon and northern California. Herein, an identity crisis would arise. John Enos--guide for both the Bonneville and Fremont expeditions into Oregon--was a master of the English language. He could easily pass for red or white, whichever might be his choosing. Rejected by whites, he became a disciple of another disenchanted tribesman, Tom Hill. On King John's call, Enos rode into southwestern Oregon to rally the various tribes into a fighting unit. Chetco Jenny, Rogue girl and official 500-dollar-a-year interpreter for Indian Agent Ben Wright, was to furnish the link with which to mold the tribes together. Enos suspected that Jenny was welcome in the privacy of Wright's cabin but very unwelcome in public. He was right. Shortly after Enos' arrival in the Rogue camps, Wright, in a drunken rage and to the delight of jeering miners, settlers and soldiers, "stripped Jenny stark naked and horse-whipped her through the streets of Port Orford." Jenny was very much in love with Wright, but this humiliation aroused such flaming hatred in her heart that she vowed to even the score. On the night of February 22, 1856, a Washington Anniversary Ball was held at Gold Beach. Among others attending the event was Capt. John Poland with most of his volunteers, leaving only 10 men to guard their camp a few miles up Rogue River. He had a message for Capt. Wright. Jenny had forgiven his outburst, and if Wright would meet her at his cabin she would--among other enticing promises--lead him to the hideout of the notorious Snake, John Enos. Wright was on his way. The following morning at daybreak, Capt. Poland, on his way back to camp from Gold Beach, stopped to see Wright and offered to go along to help arrest Enos who, according to Jenny, was hiding out on the Coquille River. Wright was so eager, as he followed his dark-eyed beauty through the brush, that he never noticed that Poland was no longer with them. The last sound he ever heard was Jenny's saucy laughter as a knife slipped between his ribs. Enos ripped out Ben's heart, and rumor has it that together he and Jenny ate part of it to make them strong. [Page 267] Gale Ontko, Thunder Over the Ochoco, vol. II, 1994 Ontko confabulates John Enos of Fort Washakie with Enos Thomas, the Canadian Indian of Gold Beach. Several Indians claimed to have been guides of John C. Fremont; it may be a coincidence that two Indians named Enos made that claim. It seems more likely that either Enos Thomas took advantage of the similarity of names to claim to be the Fremont guide--or it may have been an assumption on the part of the whites. The Rogue River War.

February

1st,

1856.--

. . . In regard to the Indian prisoner, I may remark that he was a

partner of Enas, the Canadian Indian who was with the party that was

cut off near the mouth of the Illinois a few days ago. I have already

mentioned that Enas brought the news of this misfortune to the mouth of

Rogue River. On his arrival at the latter place the citizens were

induced to let him carry an express to the volunteers at the Big Bend,

informing them of what had transpired, and that a hostile band was in

their vicinity. They also let him have about sixty dollars worth of

gunpowder, which he said the captain of the volunteers desired him to

get--for which he paid in gold slugs. Several persons offered to go

with him, but he declined their company, saying that he could go more

expeditiously and safely alone. Jerry McGuire (acting Indian agent) has

since been at the Big Bend, and given Captain Poland the first

information concerning the action of the hostile Indians in his

vicinity. Enas had not arrived. Captain Poland denies having requested

him to buy ammunition, or giving him any gold slugs; and as Enas

possessed none himself, it is believed that he has been double dealing,

and that the ammunition was purchased for the hostile Indians. Another

way the latter have of getting ammunition is from the squaws kept by

some of the miners. [page

273]

Port

Orford, Feb. 1, 1856.

Editors Alta.--With

the exception of the murder of two men, the particulars of which I give

below, nothing of importance has occurred in Southern Oregon. About two

weeks since a party of volunteers posted near the Big Bend of Rogue

River was surrounded by four or five times their number of Indians, but

after a day's skirmishing the Indians retreated, taking with them a

number of mules belonging to the camp. Maj. Reynolds, at this post, has

dispatched a train with provisions to the camp.

On the 23rd ultimo, two men named Huntley and Clevenger were going to the Rogue River, accompanied by an Iroquois Indian (Eneas) and one of the Tututni tribe. They had encamped below the mouth of the Illinois River the night previous and were intending to separate--Huntley and Clevenger to go up to the Big Bend on the south side, and Eneas and the Indian to go with the provisions. They had not proceeded far when they heard a voice hallowing in the woods. They stopped and scrambled up the bank; when they had scarcely shown themselves when they received a volley, and Huntley and Clevenger both fell. Eneas, the Indian, succeeded in getting off to the canoe, but his Indian companion was also killed. A volunteer party is to start in a few days for the Big Bend. Major Reynolds, at this post, declines sending the solicited body of twelve men until he hears from the sub-Indian agent at Rogue River--Jerry McGuire. There seems to be no doubt that the Indians are being driven towards the coast, and that we may yet have a chance for a brush with them. Daily Alta California, San Francisco, February 5, 1856, page 2 The letter is unsigned. *

* *

Monday, Feb. 25th, 1856.--Indian

troubles are augmenting. Captain Ben Wright, the Indian sub-agent,

Captain Poland, several volunteers, and all the settlers between this

and Rogue River, except those immediately at the mouth, making about

twenty-eight in all, have been massacred by the Indians.As previously mentioned, the friendly bands from the vicinity of Big Bend of Rogue River had been brought lower down the river, so as to keep them separated as far as possible from the hostile tribes above. Provisions were also issued them by the agent, whose intention it was to remove them, together with all the tribes in this district, to the Indian reserve selected by the superintendent last summer. The Indians seemed delighted at the idea of going on the reservation. About fifteen of Captain Poland's volunteers were kept in the neighborhood to watch their movements. On the twenty-second instant five of these attended a ball at the mouth of the river. On the same day the Indians (those brought from the Big Bend) sent a message to Captain Wright that Enas (the traitor) was at their camp, and desired Wright to come up immediately, as he wished to have a talk with him. The latter returned answer that he would meet Enas at a halfway house; and accordingly left the same day with Captain Poland for the place of assignation. That night the ten volunteers, who were quartered in a shanty directly across the river from where the agent and Enas were to meet, heard a very suspicious noise in that direction, but did not know that anything was wrong till the following morning, when their party was attacked whilst at breakfast by an overwhelming body of savages. They immediately broke for the thicket. So far but one of them (C. Foster,) has been heard from--and he managed to reach this place. He lay secreted in a thicket near the attacked house all day Saturday, and saw sufficient of the Indian movements that day to satisfy him that all the coast Indians in that vicinity had risen against the whites. Foster says he killed two Indians with his revolver, and could have killed a third, but was afraid the report of the pistol would endanger his life. On Saturday night he left the thicket, and came as far as Euchre Creek, On coming near the ranches there he discovered them burnt, and the Euchre Indians holding a war dance. Last night he reached this place. Shortly after, a schooner arrived from the mouth of the Rogue River confirming the report of the outbreak. She left yesterday morning; she brought a list of the missing, twenty-eight in number. The nearest house burned is within fifteen miles of here. As the Indians are vastly stronger than the whites, even though the bands between this place and the Coquille do not join them, and as they are elated by almost unprecedented success in upper Rogue River, and led on by that rascal Enas, who, from having been employed so much by the army as guide, has a perfect knowledge of this country and its most assailable points, it is feared an attack will be made on the citizens in the temporary fortifications at the mouth of Rogue River, and perhaps on this place. [page 282] *

* *

[May 2,

1856] . . . she informed the

interpreter that she belonged to the Tututnis,

and had been sent

by the Rogue River Indians to request the Port Orford band to tell the

whites that they were tired of fighting, and desired peace; that the

upper Rogue River Indians, and Enas, who had inveigled them into making

war on the whites, had basely deserted them--that all their ranches and

provisions were destroyed--many of their number killed and wounded,

that they were nearly starving, and were desirous of peace, and were

willing to come in and submit to anything the troops desired. [page 319]Dr. Rodney Glisan, Journal of Army Life, 1874 An Indian by the name of Enos, and two other Indians, had also started for Big Bend on the morning of the 22nd, fell in with Huntley and Clevinger, and camped with them the night previous to the attack. One of the Indians was killed in the fray, but Enos and the other escaped, and brought information of the tragedy to the mouth of Rogue River. Enos shortly pretended to return to Big Bend, but has not been heard from since. Some of our citizens suspicioned him as a traitor at that time, but let him go. . . . Agent McGuire arrived here on the 28th and arrested an Indian by the name of Ben, said by some to be a Klickitat and partner of Enos, against whom, the agent says, sufficient evidence exists for his being taken and killed by whomsoever he may be found. He is a large man, his hair cut straight round his neck, nearly blind in one eye, has some arrow scars close to one eye, other scars about his person, and is known as one of Col. Fremont's guides in Oregon and California. Ben has been sent to Port Orford. Crescent City Herald, February 13, 1856, page 1 The Indians are commanded by a Canadian French man named Aenas, formerly of Hudsons Bay notoriety--the fellow who once traveled over California with Fremont. R. W. Dunbar, letter to Joseph Lane dated March 15, 1856, Joseph Lane mss 1835-1906, Lilly Library, Indiana University This Eneas is a Canadian Indian, and has been in Oregon for several years, and talks several different languages. He had professed a great friendship for the whites, but sometime during the month of January he deserted the cause of the whites and joined the belligerent band of Indians. Governor I. I. Stevens, Port Orford, March 8, 1856, in "Official Account of the Indian War in the North," Sacramento Daily Union, March 22, 1856, page 1  The mouth of the Rogue River in the 1930s. THE ROGUE RIVER WAR.--Through the politeness of Dr. Holton, who arrived on the Republic from the fort at the mouth of Rogue River, via Port Orford, we learn that in attempting to open a communication between Port Orford and that place, by sea, a whaleboat was capsized, containing eight men from Port Orford, six of whom were drowned; the other two succeeded in getting into the fort. At the time the doctor left (6th inst.), they had succeeded in redeeming Mrs. Geisel, daughter and infant about six weeks old--her husband and three sons having been killed in the attack of the 22d February. On the 2d inst., five white men and one negro left the fort for the purpose of securing some potatoes that were not destroyed by the fire at the mouth of the river, [and] although well armed, [they] were cut off and every man killed, since which time no persons have ventured to leave the fort, forty men being kept on guard day and night. The whole number of persons in the fort being 26 men (five wounded), 7 women and 12 children. Old Enos is the leader of the savages, who boasts, with others, that they have plenty of ammunition and arms, and only sold Mrs. Geisel and her family to the whites from the fact that they soon expected to take the fort with all its inmates and establish an Indian town upon its ruins. Only about 60 guns are in the fort, and the supplies are reduced to about six days' rations. The Indians have made three attacks, but were repulsed each time, losing some few of their number, but they have not as yet made a general charge; and for lack of numbers no sally has been made from [the] fort. As no communication is kept up between the parties, they learned from Mrs. Geisel (who was a prisoner with the Indians for nine days) all further particulars respecting their views and intentions. She states that the Indians are very sanguine that they will entire overcome the whites and secure the immediate possession of the fort, as it is supplied by a small running stream, which the Indians threatened to cut off, but which, as yet, has not been done. A communication is kept open with the beach, a distance of some fourteen yards, from which place they secure their firewood. The doctor left the fort as messenger to Port Orford, by means of a whaleboat sent from that place. The Republic on her return trip landed at Port Orford some 73 regular troops, which added to the 42 landed by the Columbia as she went, and those already stationed there amounts to 175. These troops are under the command of Major Reynolds, who sent a dispatch to Col. Buchanan for the purpose of securing his cooperation. Mrs. Geisel and her infant were received in exchange for two squaws, who were prisoners in the hands of the whites. Her daughter was purchased at something of a cost. At the time of capturing Mrs. Geisel, on the night of the 22d of February, her hands were tied behind her, and she was compelled to witness the murder of her husband and children, as well as the most savage mutilation of their bodies after death, when she was conducted to like horrible scenes upon the persons of many of her friends and relatives. A house containing six of the volunteers was attacked at daylight, and not until the afternoon were all the inmates slain. Five of the volunteers got into the fort, some of them having their feet frozen and existing without food for five days. The whole loss of the whites is about twenty-six killed and five wounded. The names of the wounded are James Hunt, Edwin Wilson, N. B. Gregory, Geo. Basset, and one unknown. The Democrat, Defiance,

Ohio, May 3, 1856, page 2 This account was taken from the Crescent

City Herald of March

12. It was also printed in the New York Times of April 17, 1856.

PIONEER SKETCHES.Last evening an old squaw came in from the Indian camp, and is now in confinement, where I shall keep her until she is able to give some account of herself which from exhaustion caused by fatigue and hunger she was not able to do then. All that she did say was that she had a talk for the white men from the Indians who did not want to fight anymore, and that they had had a great many killed. . . . I have just heard the interpreter's report of his conversation with the old squaw. She says that she "was sent up by the hostile Indians to see if the friendly Indians were still here, and if so to say through them that the others are very anxious to make peace and surrender themselves unconditionally. They have had their houses burnt, their provisions destroyed, are without clothing, and have lost a great many of their people, both men and women, wherefore they desire to make peace and are willing to do whatever the whites may require. Furthermore, they say that they were persuaded into this war by the bad advice of Enos, who told them that the white men were afraid of them, which was the cause of their treating them so kindly, and now he has left them and gone up the river with the upper Indians who took with them, when they went away, everything that the whites had not destroyed, for which they intend to kill him if ever he comes among them again." Major Robert C. Buchanan, letter of May 1, 1856, NARA M689, Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General 1881-1889, Roll 567, Papers Relating to the Death of Mary Wagoner. Tuesday, May 6th. camp mouth of R. R. Weather pleasant--no signs of Col.--In camp mouth of R. R.--express left for Fort Orford--I sent report to Col. B.--and asked for some clothing &c.--Capt. S. also sent letter reporting that squaws think attack can be had &c.--3 P.M. Col. arrived with long looked for letters from home--all well thank God--Capt. Augur & train in--told Col. of volunteers having sent two squaws (as I just learned) to say if the Indians wanted peace they must send in the head of Enos--Col. in a rage at it-- Diary of Captain Edward O. C. Ord, quoted in "The Rogue River Indian Expedition of 1856," master's thesis of Ellen Francis Ord, 1921 We have at length full confirmation of the fact that a battle was fought on Rogue River, between Captain Smith's command and the Indians, in which Captain Smith lost eleven killed and twenty-one wounded. The report heretofore published is, in the main, correct. We obtain this news from the Yreka Union extra, of the 18th June. It is made up from the extra of the Jacksonville Sentinel of the 14th. There had been a consultation with the savages about the 1st of June, which resulted in nothing. The report proceeds: About the 5th of June, Captain Smith, in command of some eighty regulars, advanced about fifteen miles above Col. Buchanan's command, and encamped near the Big Bend of Rogue River. In the evening, old George informed the Captain that the movements of the Indians looked suspicious. Captain Smith, after dark, moved his camp further up the mountainside, and posted double guards. During the night the Indians, under old John and Enos, surrounded the camp, and about sunrise in the morning fired on the guard, killing eleven men and wounding twenty-one. The battle continued until next day about noon--thirty-six hours. During the battle two Rogue River Indians were with Captain Smith, and stated that they understood the conversation that was going on between John and Enos. They heard John say, "Enos, you have always told me that you could whip the soldiers; now, if you can, why don't you charge on them with your knives and kill them, and save your powder and balls?" He accordingly made the charge, but did not effect anything. During the battle old John was seen swinging ropes, and was heard to say that he intended to hang Captain Smith. The Indians obtained the body of one of the dead soldiers and hung it up, and tied a stick on the shoulder to represent a gun. "Indian Hostilities on Rogue River," Sacramento Daily Union, June 24, 1856, page 1 The following information, which is later, was communicated to the editor of the San Francisco Globe, by Col. R. N. Snowden, who arrived in San Francisco on the Goliah: Enos, the Canadian Indian, well known as Col. Fremont's guide in his first expedition to California, and more recently famous for the influence which he exercised among the different tribes of Indians from Oregon to Southern California, was dangerously wounded in the battle. His squaw was captured, and she reports that he cannot survive the wound. He was shot in the neck and in the knee. "The Indian Battle at Big Meadows," Sacramento Daily Union, June 26, 1856, page 3 I hope that you will take some means to render some security here in life and property. From the best accounts that I can gather that Enos, the notorious robber, has between 30 & 50 Indians with him or at his command that won't leave this section of the country. I would suggest that there be a reward offered for Enos dead or alive, as he is beyond a doubt an outlaw, and all his party or their chiefs have treated and left the country. I think if a liberal reward was offered for those outlaws that there would be men enough that would soon close the present difficulties. I would suggest that one thousand dollars be offered for Enos dead or alive and two hundred apiece for the others, dead or alive. I suppose that they all would have to be taken dead unless it was by chance. This mode would be much cheaper, and I think more effectual. There should be something done soon, that the farmers could work with some security. Letter, Lt. G. W. Keeler to Adjutant General E. M. Barnum, July 26, 1856; Oregon State Archives, Yakima and Rogue River War, Document File B, Reel 2, Document 596 Your favor of yesterday advising me of the arrest of Eneas has been received, and in reply I have to suggest that he be retained by you at the Grand Ronde until I can confer with Chief Justice Williams of Salem to ascertain whether a special term of the court may not be convened to try this particular case. Had he been taken during the time of actual hostilities, the military would undoubtedly have been competent to try his case, but now, after the restoration of peace, it may be a question whether the correct mode would not require a trial by the civil authorities. There is no doubt of his having incited the Indians to take up arms, and of his personal participation in the murder of Ben Wright and Poland, but whether such evidence can be brought before the court to convict is yet to be ascertained. Indian evidence against an Indian however will undoubtedly be regarded as good, and of this I presume there is a sufficiency. I will advise you of Judge Williams' reply on the return of my messenger, and hope to be at Grand Ronde in a few days. Letter, Indian Superintendent Joel Palmer to Captain DeLancey Floyd-Jones, July 28, 1856. Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 6; Letter Books E:10, page 195. Office Supt. Ind.

Affairs

SirDayton O.T. July 28th 1856 We have recently arrested on the Coast Reservation the notorious Eneas of Lower Rogue River, who has been regarded as the direct cause and controlling spirit in the outbreaks by Indians against the whites in the Port Orford District, and who it is alleged made the assault in person and killed by his own hand Capt. Ben Wright and aided in killing Capt. Poland. In the surrender of the Indians of that district, they were given to understand that this man would be executed if taken. It is believed he came here to excite a revolt, but was informed of by an Indian chief belonging to Port Orford, and assisted by C. M. Walker, aided by the military stationed at the mouth of Salmon River. My object in writing is to ascertain whether a special court may not be called to try this prisoner, or whether in your opinion he may properly be tried by court martial. You are aware we have no jail, and his presence may cause trouble on the reservation. If his case could be disposed of at once, it would undoubtedly subserve the public interest. Please advise me by return messenger. He is now or will be this evening at the Grand Ronde in the custody of the military, whom I have requested to retain him until your decision shall be known. In the event of a protracted postponement of trial we shall be compelled to send him to Vancouver for safekeeping. Will you have the kindness to advise me what steps should be taken to secure a speedy and legitimate trial of this Indian? The magnitude of the crimes alleged against him demands attention, and the chance of escape being so great it would be wise to dispose of it at the earliest possible moment. Will Indian testimony be regarded as good against an Indian? This question may have an important bearing in this case. I have the honor to

be

ToDear sir Your obt. servt. [Joel Palmer] Hon. Geo. H. Williams Chief Justice U.S.C. Oregon Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 6; Letter Books E:10, page 196. Office Supt. Ind.

Affairs

Dear sirDayton O.T. August 2nd 1856 (written at Grand Ronde) Referring to my letters of 28th ultimo, requesting the retention of Eneas at the Grand Ronde until it could be ascertained whether a court could be convened to try him, I have now to submit a copy of a letter from Chief Justice Williams upon that subject. The presence of this Indian at the Grand Ronde is calculated to cause excitement among the Indians. It is therefore important that his case should be attended to at an early day. The witnesses against the prisoner being among the coast tribes, it is submitted whether it should not be well to have the case tried here or on the coast, but in the event of a conviction it may not be advisable to execute the prisoner at this encampment. I am satisfied that unless he be tried by a military commission, great delay and uncertainty must ensue, as he must necessarily be taken to the county in which the offenses was committed for a judicial investigation, and I concur with the judge that under the circumstances a trial by a military commission is the proper mode of proceeding and therefore express a hope that measures may be taken to carry it into effect at the earliest practicable moment. I am, sir, yours

&c.

To[Joel Palmer] Capt. De L. Floyd-Jones of 4th Infty. Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 6; Letter Books E:10, page 199. To Col. S. Cooper Adjt. Genl. U.S.A. Washington D.C. Upper

Post, Coast Reserve, O.T.

Major--August 4th, 1856. I have the honor to report that the half-breed Eneas, who murdered the Indian Agent Wright in February last, and who was one of the principal instigators of the outbreak upon Rogue River, and who was regarded by Col. Buchanan as an outlaw, was apprehended by a party of my men on the 29th ult., and has been detained at this post until the present time, in consequence of a suggestion of Superintendent Palmer to that effect. Finding however as you will [illegible] from the enclosed letters that it is not now the wish of Palmer to try said prisoner by a civil tribunal, it is my intention to send him to Fort Vancouver for safekeeping. I shall also visit Fort Vancouver and lay the case before Col. Wright, the district commander; Should he decline ordering a commission for his trial, which is not improbable, as his jurisdiction may not extend to the Coast Reserve. I have to request that a commission be at once ordered for the purpose indicated. I enclose herewith a list of witnesses in the case. The charges against Eneas are not enclosed, as all the data necessary cannot at once be collected; sufficient evidence however can be procured for his conviction either as an outlaw or as a traitor. Witnesses against half-breed Eneas Charles

Forster

Fort

Yamhill Letterpress Copy Book, University of

Oregon Special CollectionsMaster Charles Durno, Port Orford P.S. I also send you herewith enclosed the telegraph dispatch which I received from the Superintendent, as it requests me to send to you for Eneas, to be brought immediately to Vancouver. I sent express on yesterday with one from Capt. Jones, but as it did not state where to send him, I now forward you this one. . . . Letter, H. P. Goodhue, Office of Indian Affairs Clerk, to Lt. W. B. Hazen, August 8, 1856. Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 6; Letter Books E:10, page 203 ENOS.--It will be seen by the following extract from the Oregonian that "Old Enos," who has been supposed to be still at large making mischief with a few of the Chetco and Pistol River Indians, has been taken and will be tried for the murder of Ben. Wright. We hope he may have an opportunity of testing the strength of hemp. "We understand that Enos, the Indian who murdered Benj. Wright, was captured a few days ago on the reservation, and is now in irons awaiting his trial. He was guide for Wright, it will be remembered, and it is said he stabbed Wright in the back while he was pleading with the rest of the Indians for his life. He will probably be tried by a military commission, as Judge Williams, whom General Palmer had requested to try him, had so recommended. This Indian is intelligent and educated, but has been very treacherous, and one of the principal leaders in the disturbances at the south. If we are not mistaken, he is a half-breed Red River Indian, and well known as one of Col. Fremont's guides through the country in '43 and '44." Crescent City Herald, August 20, 1856, page 2 Proceedings of a

Commission

Convened at Fort Vancouver, W.T. by Virtue of the Following Order, Viz.: Headquarters,

Department of the Pacific

Special Orders

No. 96Benicia, California, September 3, 1856 A commission will meet at Fort Vancouver, W. T. on the 15th day of September 1856 at 10 o'clock a.m., or as soon thereafter as practicable, to investigate the charges made against the half-breed Indian, Eneas (now in custody of the military authority) in relation to his conduct during the Indian disturbances on the Rogue River. The Commission will report the facts in the case. The Commission will be composed of Lieutenant Colonel Thompson Morris, 4th Infantry; Captain Rufus Ingalls, Quartermaster's Department; Captain Henry D. Wallen, 4th Infantry. By command of Major General Wool, W.

W. MACKALL,

Assistant Adjutant General -----

Fort

Vancouver, W. T.

The

commission met pursuant to the above order. Present: 10 o'clock a.m., September 15, 1856 Lieutenant

Colonel Thompson Morris, 4th Infantry;

The

junior member recording the proceedings.Captain Rufus Ingalls, Quartermaster's Department; Captain Henry D. Wallen, 4th Infantry The accompanying papers, marked A, B, C, and D, in reference to the charges against the half-breed Indian, Eneas, were then presented and read to the Commission, by the Recorder, when they adjourned to meet again tomorrow, at 10 o'clock a.m., 16th instant, to enable the Recorder to prepare the proper charges and specifications against the prisoner. H. D. Wallen Captain, 4th Infantry Member & Recorder T. Morris Lieut. Col., 4th Infantry President of Commission -----

Fort

Vancouver, W. T.

The commission met pursuant to adjournment.

Present: 10 o'clock a.m., September 16, 1856 Lieutenant

Colonel Thompson Morris, 4th Infantry;

The proceedings of

yesterday, the 15th instant, were read over by the Recorder and the

charges and specifications as drawn-up were submitted and approved.Captain Rufus Ingalls, Quartermaster's Department; Captain Henry D. Wallen, 4th Infantry As no authority is given in the order organizing the Commission, which authorized the sending for persons to substantiate the allegations made against the accused; and as many of the witnesses will have to be summoned from a distance for this purpose, and as it is possible that they may all have to return to the place of sitting of a Military Commission or Court-Martial, if either be ordered in this case, the Commission deem it proper and prudent to submit these proceedings as far as they have progressed to the Major General, Commanding this Department. The Commission, therefore, adjourned until the proceedings are submitted and a reply is received from the Headquarters of the Department of the Pacific. H. D. Wallen Captain, 4th Infantry Member & Recorder T. Morris Lieut. Col., 4th Infantry President of Commission -----

Statement

of Capt. Floyd-Jones

Dayton,

Oregon Territory

Colonel: It

appears that some time last winter, a volunteer company was formed at

the mouth of Rogue River, which had for its object the protection of

the settlers, as also the calling off of the communication between the

upper & lower Rogue River Indians. For this purpose,

it

took place on the river at a point called "Big

Bend." Eneas,

having subscribed to the Rules and Regulations and signed his name, was

regarded as one of the company which was commanded by Captain John

Poland. Eneas continued to perform his duties as a member of

the

company, without suspecting him of treachery until the 27th of January,

when he started up Rogue River in company with John Clevenger and Enoch

Huntley, who had in charge a supply of provisions for their comrades at

the Bend. On reaching the mouth of the Illinois, the two white men

above named were waylaid and murdered, Eneas immediately after

returning to the mouth of the river and reporting that all had been

attacked, and that he barely escaped with his life, his story was so

plausible that at first he was not suspected by the community in

general of being their betrayer, notwithstanding a messenger was

dispatched to alarm the party at the Bend and put them on their guard.

Eneas at the same time started up the river as express to deliver a

dispatch to Captain Poland, which, of course, he never received. From

that time forward he was regarded as a traitor, and a plan was laid by

Benjamin Wright, sub-Indian agent, for his arrest, which he attempted

to carry into effect on the night of the 23rd of February, but which

resulted not only in his, Wright's, death, but that of several others.

I should have stated also that between the dates mentioned above, the

27th of January and 23rd of February, every indication intended towards

the fact that Eneas was inciting the Indians to revolt. At the murder

of Wright, which occurred early on the morning of the 23rd February, he

was the principal leader, although many others participated in it, and

at the subsequent massacres, which occurred on the same day, he took an

active part. He commanded in the various little skirmishes that took

place in the vicinity of the fort

to which the citizens of lower Rogue River retreated, after the morning

of the 23rd February, and in negotiating for the exchange of Mrs.

Geisel, he acted as their chief. He also admitted to me that he was

present at the fight at the Mikonotunne village.September 12, 1856 As to his treachery and of his inciting the lower Rogue River Indians to rise against the inhabitants, there is abundant proof. I have no doubt too that there is sufficient evidence on the reservation to prove that he not only betrayed Huntley & Clevenger, but that he also participated in the murder of Wright, but it would be much more difficult to obtain. I would, therefore, suggest that the charge or charges be made with reference to inciting the Indians, and leading them in their hostilities against the whites. The witnesses are given in the order of their importance, and I would state also that the Indian witnesses are much more likely to testify correctly apart from the reservation than upon it. My own name is given, as he made quite a lengthy statement to me on the morning of this arrest. Witnesses:

Peter McGuire (in Indian Department) Indian Chief Joshua Charley (of Joshua's band) Relf Bledsoe (in Indian Department) Kitty (squaw at Port Orford) Captain DeLancey Floyd-Jones, 4th Infantry Respectfully

submitted,

To: Colonel

Thompson Morris, 4th InfantryDeLancey Floyd-Jones, Captain, 4th Infantry President, Commission, Fort Vancouver, W.T. -----

Charges and

Specifications preferred against the half-breed Indian, Eneas, now in

custody of the Military Authority at Fort Vancouver, W. T.Charges & Specifications Charge 1st, "Desertion." Specification. In this, that the half-breed Indian, Eneas, being a member of Captain John Poland's Company, Oregon Territory Volunteers, organized for the protection of the settlers at the mouth of Rogue River on or about the [blank] day of [blank] 1856, and stationed at a point on said river known as the "Big Bend," did desert from said company and go over to the enemy, the Rogue River Indians, with whom the whites were at war. Charge 2, "Murder and Inciting to Massacre." Specification, 1st: In this, that the half-breed Indian, Eneas, did after his desertion from Captain John Poland's Company, Oregon Territory Volunteers, act as principal leader in the murder of the sub-Indian agent, Benjamin Wright, on or about the morning of the 23rd day of February 1856, and in the murder of Captain John Poland, O. T. Volunteers at [blank] on or about the [blank] day of [blank] 1856. Specification, 2nd: that the half-breed Indian, Eneas, did after the murders aforesaid act a principal leader, or did participate in the several massacres that occurred at [blank] on or about the 23rd day of February 1856, and did cooperate in, or incite to, the various massacres that occurred in the Rogue River country, pending the hostilities that existed between the Indians there located and the whites. Henry

D. Wallen,

Captain, 4th Infantry Recorder of Commission Witnesses

for the Prosecution:

RG 393, Department of the

Pacific, Letters Received, 1856General Palmer Captain Floyd-Jones Indian Chief Joshua Charley, Joshua's band Relf Bledsoe, Indian Department Peter McGuire, Indian Department Kitty (squaw, Port Orford), wife of Tor-to-tony. Captain Tichenor, Astoria, Oregon Territory Witnesses for Defense: John, Indian chief, reservation George, Indian of John's band, reservation Bill, Indian of John's band, reservation CAPTURE OF AN INDIAN CHIEF.--We are indebted to Mr. W. W. Baugh, the Oregon messenger of the new American Express Company, for information that Enos, the celebrated chief of the Indians around Port Orford, who was recently captured in Oregon, was brought down the coast from Portland by the steamer Columbia. Enos is well known as having been Fremont's guide in his first expedition across the Plains. Some twelve months ago, the Indian agent Wright, with some of his party, was murdered by the Indians of Port Orford, under the command of Enos. The latter escaped, and was but lately captured. The weather being rough at Port Orford, the Columbia did not touch there to land him, but put ashore at Crescent City. The prisoner is under charge of Sheriff [Michael] Riley of Port Orford, who will proceed to that place as soon as opportunity offers, so that Enos may stand his trial there on a charge of murder. San Francisco Bulletin, March 17, 1857, page 3 Resolved,

by the Board,

that the bill of M. Riley, Sheriff, for fees & expenses in executing the warrant and arresting Enos Thomas, charged with murder, and bringing him to this county for examination, amounting to the sum of two hundred twenty-eight 75/100 dollars, be allowed and an order on the treasurer be issued therefor. Curry County Commissioners'

Journals, Vol. 1, page 28

Resolved,

by the Board,

that the bill of Wm. M. Copeland, Justice of the Peace, for justice fees, in the case of the people vs. Enos Thomas, amounting to two dollars and sixty-five cents ($2.65) be and the same hereby is allowed, and that an order on the treasurer be issued therefor. Curry County Commissioners'

Journals, Vol. 1, page 32

Resolved,

by the Board,

that the bill of M. Riley for balance on bill for making the arrest of Enos Thomas, amounting to ninety-five dollars, be and the same hereby is allowed, and an order on the treasurer issued therefor. Curry County Commissioners'

Journals, Vol. 1, page 37

Resolved,

by the Board,

that the bill of Wm. J. Berry, for taking irons off of Enos Thomas 11th of April 1857, amounting to the sum of five dollars, be allowed and an order on the treasurer be issued therefor. Curry County Commissioners'

Journals, Vol. page 56

Unsigned letter dated April 16, 1857, Oregon Statesman, Salem, May 12, 1857, page 2 LYNCHING IN ROGUE RIVER VALLEY.--A passenger who arrived by the Columbia yesterday informs us that an Indian was hanged at Rogue River last Monday for the murder of Mr. Geisel, committed some two years ago. The murder was a cold-blooded atrocity, and created much feeling at the time. Geisel was married and had three children. He was killed in his bed asleep, and two of the children were murdered. Mrs. Geisel and one child were carried into captivity, but were afterwards exchanged for some Indian prisoners. The perpetrators escaped, but were held in memory, having been recognized by Mrs. Geisel. A few days ago, as they were going by Rogue River, on the way to the reserve, this man was seized and tried, but owing to the absence of Mrs. Geisel, no evidence could be brought against him. The people, however, were satisfied of his guilt as he was well known to them, and on his being released by the legal authorities they seized him and hanged him on a tree. They then got out a warrant for four or five concerned in the murder, and arrested them. They are now awaiting their trial. Daily Alta California, San Francisco, March 8, 1858 [sic], page 2 Despite the incident's similarity to the hanging of Enos in 1857, this article refers to the hanging of Chetco Bill in 1858 for the murder of John Geisel. HUNG BY THE PEOPLE.--The people of Rogue River Valley, says the Alta [California], hung an Indian on the 1st inst., for the murder of Mr. Geisel, about two years ago. The murder was a cold-blooded atrocity, and created much feeling at the time. Geisel was married and had three children. Mrs. Geisel and one child were carried into captivity, but were afterwards exchanged for some Indian prisoners. The perpetrators escaped, but were held in memory, having been recognized by Mrs. Geisel. A few days ago, as they were going by Rogue River, on the way to the Reserve, this man was seized and tried, but owing to the absence of Mrs. Geisel no evidence could be had against him. The people, however, were satisfied of his guilt, as he was well known to them, and on his being released by the legal authorities, they seized him and hanged him on a tree. They then got out a warrant for four or five concerned in the murder, and arrested them. They are now awaiting their trial. The above occurred at the mouth of Rogue River, we believe. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, March 27, 1858, page 2 . . . although the little settlement now grew and prospered, yet Battle Rock was destined to be the scene of another tragedy connected with the Indian race, which occurred in this wise: At the time of the breaking out of the Rogue River war, one of the most sanguinary and stubbornly contested of the conflicts of the white and Indian races on the coast, there lived at the little town of Ellensburg, at the mouth of the river, an Indian named Enos. He was from an eastern tribe--I believe the Cherokee--and had come out to the western coast on a whaling vessel, and drifted up to this settlement in Oregon. Dressing after the fashion of the whites, speaking their language fluently, having no intercourse with the natives, and being besides quite industrious, he was regarded with great confidence by our countrymen. At this time the tribes at the mouth of the river had not broken out in open hostility, although fighting was going on in the Rogue River Valley well up the stream. Two white men, desirous of joining the volunteers on the upper river, engaged Enos to accompany them. They supplied him liberally with ammunition and arms, and expected to find him a useful auxiliary. The three men departed together, and nothing more was heard of them for a long time. Subsequently, to the great surprise of the white men, Enos was discovered as a leader of one of the most warlike and brave of the bands of their enemies. This led to a search, and the skeletons of his two companions were discovered beside the ashes of a campfire--evidently murdered in their sleep by their treacherous ally. After various mutations, the war was closed by the surrender of a large body of Indians, among whom was Enos. They were removed to the reservation at Vancouver, under the charge of the United States authorities. But Oregon justice was not to be thus easily satisfied. The widows of the two murdered men cried out for revenge. A warrant was sworn out for the apprehension of Enos on the charge of murder committed before actual hostilities had broken out, and therefore rendering him amenable to civil authority. The sheriff of the county proceeded to the reservation and demanded the body of Enos. The lieutenant in command yielded him up, and he was conveyed in irons to Port Orford, the county seat. Of this journey down, the sheriff, who is still living, relates the following anecdote: Enos wished to exchange the dirty shirt that he wore for a clean one, but his custodian refused to unlock his handcuffs. Nevertheless he is said to have actually accomplished the apparently impossible feat of taking off the soiled garment and replacing it with a clean one, by drawing both through his irons. Arrived at Port Orford, the criminal was tried before a regular court. There was, however, no evidence to prove that he actually committed the murder, and he was set free. To use the sheriffs words: "Enos was confined in the blacksmith's shop of the village. After the decision I went in, told him that he was free, and unlocked his irons and took them off. I then led him to the door. When I opened it, I found myself suddenly pushed back. Two men stepped forward with cocked revolvers. Each seized an arm of Enos and hurried him down a lane of men, which, formed in double row, extended from the shop down to the beach and up to the summit of Battle Rock. Ten minutes after, his lifeless body dangled from the limb of a tree." And with this act of retributive justice ends the story of Battle Rock.. A. W. Chase, "The Story of Battle Rock," The Overland Monthly, February 1875, page 182 In the spring of 1856 a new complication was introduced into the troubles in Southern Oregon. The Indians of the coast had remained peaceful, though those living at and below the mouth of Rogue River were urgently solicited to join the hostiles. Their relations with the settlers and miners had been none too pleasant for a year past, and several incidents had occurred to intensify the natural feeling of race antagonism. Ben Wright, of Modoc fame, was the agent in charge of the Indians in that region, having his residence at Gold Beach at the mouth of Rogue River. At Port Orford, thirty miles north, was a military post known as "Fort Orford," and garrisoned by Captain Reynolds' company of the 3d Artillery. During the winter, and at the instance of Agent Wright, a volunteer company of thirty-three men, under Captain John Poland, occupied a strongly fortified post at Big Bend, some fifteen miles up the river, where they served to separate the hostiles from the Indians below. About the first of February they abandoned this post and returned to Gold Beach. Wright, observing the growing discontent of the natives, put forth every effort to induce them to go to the temporary reservation at Port Orford, where they would be safe from the attack of ill-disposed whites and the solicitations of hostile Indians. It has always been supposed that it was owing to the intriguing of one man that this effect was not brought about. This man was an Indian of some eastern tribe--Canadian, it was said--and had been with Fremont on his last expedition ten years before. Enos, called by the Indians "Acnes" [sic--Aeneas?] had become a confidant of Wright's to the extent of knowing his plans for the peaceful subjugation of the Indians. Enos laid with the braves a far-reaching plan to destroy utterly the small colony of whites; and this done, to join the bands of savages who were waging war, and to defeat and drive from the country the invaders who so harrowed the Indian soul. The first step in Enos' portentous plan was to slaughter Wright and the settlers along the coast. On the evening of February 22, having completed his arrangements, Enos, with a sufficient force of his Indians, fell upon the scattered settlement at the south side of the mouth of the river, and finding Agent Wright alone in his cabin, entered it seen, but unsuspected, by him, and with an axe or club slaughtered this hero of a hundred bloody fights. So died, perhaps, the greatest of Indian fighters whom this coast ever knew. Concluding this villainy, the Indians sought new victims, and during the night killed mercilessly, with shot or blows, twenty-four or twenty-five persons, of whom the list is here presented as given by various authorities: Captain Ben Wright, Captain John Poland, John Geisel and three children, Joseph Seroc and two children, J. H. Braun, E. W. Howe, Barney Castle, George McClusky, Patrick McCollough, Samuel Hendrick, W. R. Tullus, Joseph Wagoner, ------ Seaman, Lorenzo Warner, George Reed, John Idles, Martin Reed, Henry Lawrence, Guy C. Holcomb, and Joseph Wilkinson. Mrs. Geisel and her remaining children, Mary and Annie, were taken prisoners. After suffering the worst of hardships at the hands of the Indians, they were delivered from them at a later date, and now live to recount with tears the story of their bereavement and captivity. A large portion of the inhabitants had gathered on that fateful night at Big Flat to attend a dance given there, and so failed of death; and on the morrow these set out for the village, and on arriving there found the fearful remains of the butchery. The corpses were buried; and the remaining population, numbering, perhaps, one hundred and thirty men, scantily supplied with firearms and provisions, sought protection in a fort which had been constructed in anticipation of such need. Here the survivors gathered and for a time sustained a state of siege with the added horrors of a possible death by starvation. Their only communication from without was by means of two small coasting schooners which made occasional trips to Port Orford or Crescent City. The Indians surrounded them and commanded every approach by land. Meantime, the savages were not idle. Every dwelling and every piece of property of whatever description that fire could touch was destroyed. The country was devastated, and, beside the fort besieged, only the station of Port Orford remained inhabited. The buildings at Gold Beach were all burned, and an estimate of the property destroyed along the coast fixes the damage at $125,000. *

* *

Enos,

with quite a number of his followers, had joined the upriver bands, who

were lying on the river above the Big Bend. Others had gone to Port

Orford and placed themselves under the protection of the military. On

the twenty-seventh of March a party of regulars were fired upon from

the brush while proceeding down the banks of the Rogue, whereupon they

charged their assailants and killed eight or ten, with a loss to

themselves of two wounded.

* *

*

On the

twentieth of June Chief John sent five of his braves to Buchanan's

headquarters to announce that their leader would surrender on the same

terms as had Limpy, George and other chiefs, but he wished the whites

to guarantee safety to Enos, who was an object of particular aversion

to the volunteers. . . . There is a tradition in Curry county

that Enos was hanged upon Battle Rock at Port Orford; but the Indian

then executed was one of four Coquille Indians hanged for the murder of

Venable and Burton. The fate of Enos is unknown.Harry Laurenz Wells, A Popular History of Oregon, 1889, page 439 Reminiscences of the Rogue River Indian War.

As the public mind is at the present

time somewhat

agitated over Indian news generally, and thinking some of your readers

would be interested in scenes that occurred in our own state many years

ago, and being one of the party who took quite an active part in the

scenes herein related, and knowing whereof he speaks, writes S.S. in

the Grand Ronde Chronicle,

I will now proceed to relate the

facts of the

capture of Eneas, the half-breed Indian, whose savage instincts were

the cause of the death of as brave a man as ever lived, and one who had

done him many acts of kindness, and who placed implicit confidence in

him. I refer to the brutal massacre

of Captain Benjamin Wright, then acting Indian agent, on Rogue River,

on the 22d day of February, 1856.

Eneas was a Canadian half-breed Indian and had rendered services under Fremont in 1845. He also acted as scout for Wright in his famous attack on the Modocs in 1852, and was his most trusted agent in many respects. On the morning of the 22d Eneas entered the premises of Captain Wright, unsuspected of any evil design, and watching his opportunity, killed him with an ax, which was agreed upon among the Indians as a signal for a general massacre. They then, after killing Wright and Captain Poland and mutilating their bodies, cut out the heart of Wright, divided it into numerous pieces, the Indians eating it, among them Eneas. They did this to make them brave, as they considered Wright the bravest of white men, and should they eat a portion of the heart of so brave a man they would be equally as brave. After the massacre of Agent Wright, Captain Poland and nearly all of his command, besides many citizens in Rogue River, Eneas escaped to the mountains and remained there until the hostile Indians were removed to the coast or Grand Ronde reservation at the mouth of the Nachesna or Salmon River, about three miles above Siletz Bay. (The late General Joel Palmer was then superintendent of Indian affairs.) Late one summer afternoon of that year, Eneas came upon the reservation and went to the camp of Tututni John, an Indian who was in the massacre, and who had Ben Wright's scalp, and secreted himself. Just before sunset a friendly Indian by the name of Tag-o-me-sha came to the agency building in great excitement and informed Mr. Courtney Walker, who was then acting as sub-agent, that Eneas was in camp and gave information where he could be found, saying he had come to create dissatisfaction among the Indians and if he was not at once apprehended the consequences would be very disastrous and much trouble would ensue. At that time there was at the mouth of Salmon River--which is about thirty miles from Fort Yamhill, the nearest military post--between 12,000 and 14,000 Indians, consisting of the Umpquas, Rogue River, Tututnis and Port Orford tribes, many of them but a short time from their battlefields. Mr. Walker instructed me to go at once and secure the entire military force then at Salmon River (which was four soldiers), go to Tututni John's tent, arrest Eneas and bring him to the agency building--a small shake house 10x14, and the only erected there. I proceeded at once to obey Mr. Walker's instructions, procured the four soldiers, went to Tututni John's tent, placing the soldiers in such a position as to prevent his escape and demanded the surrender of Eneas. I was informed by some of the Indians that Eneas was not in the tent nor had he been there. I at once drew my revolver and pushing aside the opening of the tent entered. The first thing that drew my attention as I entered the lodge was a pile of blankets in the corner of the tent, whose unusual size suggested to me the possibility they might conceal beneath their ample folds the person I was looking for, and I at once proceeded to prospect, so to speak. As soon as I approached the blankets and commenced to explore them, the Indians commenced to talk very excitedly among themselves, and I then knew at once I should find my man. After throwing a few pairs of blankets aside, sure enough there lay Eneas, as "snug as a bug in a rug." I commanded him to get up at once, which he did, I enforcing my order with my pistol. I then called the soldiers into the tent, and then, telling Eneas to proceed with them to the agency building, assuring him that should he attempt to escape he would be shot. Upon arriving at the agency building, we bound him firmly and securely with ox chains to prevent his escaping. Mr. Walker spoke with him of the enormity of his crime, of the friendship the whites had entertained for him; the many acts of kindness they had extended to him, and informed him he would be sent at once to Fort Yamhill to be placed in charge of the military until the governor, George L. Curry, and General Palmer could be heard from. Eneas made no response to Mr. Walker's remarks, but remained in sullen silence. That night we guarded him faithfully, and the next morning before daybreak I started on horseback to Fort Yamhill--Captain E. C. Floyd Jones then in command--with orders for troops to be dispatched at once to Salmon River to remove Eneas to the military post, arriving there before 8 a.m., and that same afternoon some sixteen soldiers were dispatched to Salmon River for that purpose. After a short delay I proceeded to Dayton, the then-headquarters of superintendent of Indian affairs, to notify General Palmer of the capture of Eneas, and the same afternoon was on my way back to Salmon River. Eneas was removed from Salmon River to Fort Yamhill, thence to Vancouver, and in the spring of 1857 was taken to Crescent City on the steamer Columbia--the weather being too boisterous to land at Port Orford--thence by land to Port Orford, where he was waited upon by a select "necktie" party and hanged on Battle Rock sans ceremonie, and thus ended the career of Eneas. Sunday Oregonian, Portland,

December 14, 1890, page 16

At the time of the Indian outbreak there was a young educated Canadian Indian named Enos residing in Gold Beach, who professed to be true to the whites. A few days before the outbreak he started up the river in company with John Klevener, Huntley and another man whose name is forgotten. In a day or so he returned and reported that he and his companions had been attacked by the Indians and he alone escaped. He reported that two or three miners living on Rogue River at Big Bend bad sent him for ammunition, and he was given all he could carry. He immediately left and joined the Indians, where he became chief. During the captivity of Mrs. Geisel she frequently saw Enos among the Indians and heard him giving orders. This she reported after her return to the fort. He assisted the Indians as long as they fought. Knowing that capture meant death, he made his way through the mountains to an Indian reservation in Washington Territory. Here he was captured and taken to the barracks at Vancouver where Lieut. Macfeely commanded, and Sheriff [Michael] Riley of Curry County was notified. Mr. Riley was appointed sheriff in 1856 by the legislature when Curry County was organized. Mr. Riley made the trip to Vancouver by steamer from Port Orford and secured Enos, who was chained hand and foot. The steamer on returning could not land at Port Orford but landed Riley and his prisoner at Crescent City. As hostile Indians were yet in the woods it was considered dangerous to attempt to make the trip over the trail from Crescent City to Port Orford, so Sheriff Riley was obliged to remain with his prisoner in that town until the steamer called for them. Port Orford was then the county seat of this county. The steamer proceeded to San Francisco, from there to Portland and back, and on her way to Portland again before calling in at Crescent City. The first night that Enos was confined in the county jail someone attempted to break in the door and let him out. Every night after that Sheriff Riley occupied one of the rooms of the jail. It was considerably over a month from the time Mr. Riley left Port Orford for Vancouver until he returned with the prisoner. Mrs. Geisel, then residing at Port Orford, was the only witness against Enos, and she could not be found at the the time set for the trial, so the justice ordered Sheriff Riley to turn the prisoner loose. It was necessary to take him to the blacksmith shop to have the chains on his legs cut off. While this was being done a mob surrounded the shop, and the moment Enos stepped out he was seized and taken away. Whiskey was given him and he partly confessed to having assisted in the killing of his three companions mentioned above, on their way up the river. The next morning he was hanged on historical Battle Rock, where his body was buried. Orvil Dodge, Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, 1898, page 365 In the spring of 1857, Lt. Crook's regulars were rounding up the stragglers from that campaign. A group of volunteers, claiming Crook had flushed Enos from "his hideout in the Siskiyou Mountains," captured the elusive Shoshoni and hung him at Battle Rock--near Port Orford--on April 12. Although it is well documented in Oregon history that Enos died that day, who really paid the price for the murder of Ben Wright will never be known. It was not Enos! He aided Has No Horse throughout the Shoshoni wars, was baptized by Father de Smet in the 1860s and died a natural death . . . 43 years after his alleged hanging at Battle Rock. A likely candidate for the execution would be a Canadian Iroquois known as Eneas, who attained the rank of chief in the Yakima tribe. In this position, he tried to use his influence to prevent Black Ice and Yellow Serpent from declaring war on the whites. At The Dalles peace conference, Eneas was the last man to sign the treaty of 1855, thus adding to the Yakima's previous signing at Fort Walla Walla three weeks earlier. If it was he who atoned for Ben Wright's sins, the southern Oregon volunteers hung an innocent man. Gale Ontko, Thunder Over the Ochoco, vol. II, 1994, page 286 If Ontko's theory is correct, why isn't Enos on record as pleading mistaken identity? (Refer to how Tilokite and his fellow defendants had been lured to their doom.) Multiple witnesses identified him at Fort Vancouver; he provided a statement which apparently didn't deny his involvement. The Enos family is one of the most notable on the reservation. John Enos, the father of George Enos, Sr., resides at the Fort [Washakie], and is perhaps the oldest man of any race in the state of Wyoming. He went to California with General Fremont, the Pathfinder, in 1847, as a guide. He also remembers the exploring expeditions of Capt. Bonneville and Col. Lander into this country. Last year the old man again visited California with the Irwin Wild West Show. On his first trip with Fremont there was no San Francisco. The place was a huddle of Mexican huts called Buena Yerba. When old John saw one of the most beautiful cities in the world located on the same hills where the huts once stood, he threw up his hands in wonder and exclaimed: "White man heap much big medicine!" John Enos, as near as can be calculated, is 101 years of age. He is still in good health, straight as a ramrod, and able to take care of himself. His face is as wrinkled as the bark on an old oak tree, but his eyes have all the fire and gleaming brilliancy of youth. "Three Dead from Poison," Lander (Wyoming) Eagle, March 3, 1911, page 1

John Enos of Fort Washakie, who guided

the John C.

Fremont expeditions through the Rocky Mountains in 1846, is going blind

at the age of 102 years.

"Wyoming News Gathered from All Parts of the State," Natrona County Tribune, Casper, Wyoming, March 5, 1914, page 2 JOHN ENOS, 104 YEARS

OLD, DIES IN

WIND RIVER MOUNTAINS

The last vestige

of

sympathy for the Indians as a people was alienated by the murder,

February 22, 1856, of Ben Wright, then stationed as an Indian agent at

Gold Beach, at the mouth of the Rogue River. Wright, a fearless

fighter, had been a persistent champion of the Indians and was

recognized as a prudent and a just administrator and an advocate of

Palmer's plan of ending the war by conciliation. His slayer was a

renegade named Enos, of an eastern tribe, who had been with Fremont as

a guide, and who had so far won the confidence of Wright that he had

unquestioned access to the agent's office. Enos himself killed Wright

with an ax, following which he and his followers massacred twenty-five

other settlers at Gold Beach. The survivors fled to a fort, where they

were besieged

for thirty-five days, until relieved by a detachment of regulars from

Fort Humboldt, California. The military forces in the upper Rogue River

Valley were informed of the plight of the beleaguered people, but

feared to go to their rescue lest they should expose the settlements to

greater danger. The coast region was laid waste by Enos' Indians, and

several other residents were killed. Enos now joined the upriver

hostiles, but the coast Indians were pursued and subdued by regulars

and volunteers in a campaign which continued into April, 1856, at the

conclusion of which they begged to be taken under the protection of the

government.WHILE GUIDING HUNTING PARTY.

LANDER, Wyo., Oct. 11.--John Enos, the

oldest and most

noted Indian on the Wind River Indian Reservation, is dead. He was out

hunting in the hills near Brooks Lake with one of his sons and a party

of white hunters, and on last Wednesday just before retiring for the

night complained of not being well. Nothing was thought of the old man

until the next morning, when it was found that he had passed away

during his sleep some time during the night.

The body was packed out of the hills to Dubois, where an automobile was hired and the remains conveyed to Fort Washakie, arriving there Friday morning. Funeral services were held Saturday, being conducted by Rev. John Roberts of the Episcopal mission, and were attended by nearly all the Shoshone tribe from the reservation. John Enos was 104 years old at the time of his death. He did not belong to the Shoshone tribe, but came from some eastern tribe to the Shoshones 70 years ago. He married into the tribe and raised a large family of children. He was noted as a guide and hunter, and acted as such for some of the early explorers who came to Wyoming. He made his headquarters near where Green River is now when the Green River country was a great Indian rendezvous. He was in this part of the country during the time of Bonneville, 1831 and 1835, and was a member of a number of his exploring parties. He was highly respected by the members of the Shoshone Indian tribe and was considered to be a highly intelligent and good Indian. Enos, despite his great age, never ceased his lifelong habit of taking a bath in a spring or stream every morning, attributing his longevity to this procedure. In winter he would cut the ice on a stream that his bath might be taken. Wyoming Semi-Weekly Tribune, Cheyenne, October 15, 1915, page 3 When the perpetrators of the Gold Beach massacre were removed to the Siletz Reservation after the war, they took with them Wright's scalp, over which they held nightly dances in the effort to suppress which another outbreak was nearly precipitated. R. B. Metcalfe, then Indian agent, demanded the scalp and on their refusal to deliver it up dragged two of the murderers into his office in the face of 200 Indians and told them that unless the scalp was delivered in fifteen minutes he would kill them both. Before the expiration of the allotted time the scalp was delivered and peace was restored. Charles Henry Carey, History of Oregon, 1922, page 605 Early on the morning of February 23, before the dancers had returned to their bivouac, the guard was attacked with sudden fury by an overwhelming force of Indians. But two of the ten men were able to escape. One of these, Charles Foster, from a concealed refuge in the woods, witnessed much of the terrible mutilation and slaughter of his unfortunate comrades. He was afterward able to identify some of the perpetrators of the attack, professedly friendly Indians who had been living about the settlements. On the same day, Captain Poland, accompanied by Ben Wright, famous Indian fighter and now acting as Indian agent, was visiting at the McGuire house between Gold Beach and the scene of the massacre, preparatory to his return to camp. An Indian brought them a message to the effect that the badly wanted Indian Enos, implacable foe of the whites, was in the hands of some friendly Indians at a camp on the south shore, and that the renegade was being held for the white men to arrest. That the wily Ben Wright, so used to Indian trickery, should have fallen into this trap is to be wondered at. But the lure held out with Enos as the bait probably obscured all thought of caution. Wright had always been a hair-trigger fighter, but his snap judgments of the past had always been surefire and disastrous to his foes. When Captain Poland and Wright arrived at the Indian camp they were seized by the tricksters, killed and horribly mutilated. Wright's heart was cut out, cooked and eaten by his killers, an Indian tribute to his courage, as those who consumed of the heart of the brave fallen foe were supposed to be thereafter imbued with his lionhearted courage. Joseph L. Brogan, "Old Days on Rogue River Remembered," Oregonian, Portland, October 6, 1929, page 72 NAME OF INDIAN DEFENDED

Oregonian, Portland,

October 28, 1929, page 6Enos a Friend of Whites, but Victim of Local Ruffians.

PORT ORFORD, Or., Oct. 7.--(To the

Editor.)--I have

just read a story by Joseph L. Brogan, "Old Days on Rogue River," and I

wish to defend the good name of Enos.

Enos was a French-Canadian Indian and was a trusted guide of Fremont. In '55 and '56 we find him at the mouth of Rogue River, and on the night of the massacre mentioned in the article Enos was not with the tribe, but later we find him in the fortification with the white people. When provisions were about gone and those confined in the blockhouse were suffering with want of food, Enos volunteered one night to go down the river to a garden, where he secured a sack of vegetables, bringing them back to the people. A big feast was held, and when ready to partake of the food Enos was kicked aside by one of the white men and told to eat by himself. With drooping head, Enos left the blockade. Later he was arrested, put in irons and taken to Astoria and, after a court-martial, he was found innocent of any wrongdoing, brought back to Port Orford and taken into a blacksmith shop, where the iron bands were cut from his wrists and he was set free. Stepping out into the little street from the blacksmith shop, he was seized by some ruffians, taken up on Battle Rock and hanged. The only friend he had at the time of his death was a six-year-old girl, Ellen Tichenor, the youngest daughter of Captain Tichenor, who found her way upon Battle Rock and there hung to the feet of Enos during his last struggle, crying and pleading for his life. There are many other things to be taken up about the Indians of the Oregon coast which will be later on. I don't believe any Indian on Rogue River ever cut the heart out of a white person and ate it, as this article suggested. The Indians of Curry County were good people and badly mistreated.

FRANK B. TICHENOR.

Oregonian, Portland,

October 9, 1929, page 10MRS. VICTOR HIS

AUTHORITY

Historian Cited in Support of Disparagement of Indian Enos

WEDDERBURN, Or., Oct. 14.--(To the

Editor.)--The

characterization of the Indian Enos in the article on early Rogue River

history, to which Frank B. Tichenor of Port Orford takes exception, was

taken from Frances Fuller Victor's "Early Indian Wars of Oregon." This

book was prepared by authority of the Oregon State Legislature from

documentary evidence on file in the state archives. The historian's

work has always been recognized as valuable and reliable. Her treatment

of the Indians' side of the case is invariably fair-minded, for she

also frequently asserted that the Indians often were more sinned

against than sinning.

Her history also is authority for the incident which Mr. Tichenor cannot conceive to be fact--the cutting out of the heart of the noted Indian fighter, Ben Wright, and the eating of it by his killers. The Rogue River Indian war was not participated in solely by Curry County Indians. Shasta Costas, Chetcos, Pistol River Indians and the more northerly tribes of the Athabascan family were all at various times allied against the whites. The bands of white miners in isolated places, unprotected by United States garrisons, as was Port Orford during times of stress, often had to fight and act on the drop of a hat. Reprisal and summary justice were the methods employed to secure their survival, and the innocent often suffered on both sides. The Indian Enos might have been on good terms with those in the trading posts, but he was certainly blacklisted in the outlands--a case of the leopard which can change his spots at convenience. Mr. Tichenor states that he was hanged by a band of ruffians. According to recorded history these "ruffians" had considerable provocation and, also according to history, these "ruffians," as those in the settlements often fondly called the miners, did valiant work in the pioneering and eventual pacification of southwestern Oregon. JOSEPH

L. BROGAN.

Oregonian, Portland,

October 17, 1929, page 10

ENOS' FATE RICHLY DESERVED

Treachery of Indian During War on Rogue River Recalled.

SAN JOSE, Cal., Oct. 23.--(To the

Editor.)--There has

come to my notice an article in The

Oregonian by Frank B. Tichenor of Port Orford, entitled

"Enos, a Friend of Whites, but Victim of Local Ruffians." In the

beginning Tichenor says: "I wish to defend the good name of Enos."

My father, the late Judge Riley of Curry County, landed from a steamer at Port Orford September 1, 1852. In the spring of 1853 he came to the mouth of Rogue River, where he resided continually more than 40 years, until his death in 1903. He and my mother were among those in the fort on the north side of Rogue River during the Rogue River Indian war of 1855. Before the Indian outbreak Enos spent considerable time among the miners along the beach, occasionally being hired to shovel pay dirt into sluices. I have never heard that he was in any way badly mistreated by the whites. The following facts I learned from my father, who often related to me the history of Enos. My father was made sheriff of Curry County in 1856 by the state legislature when the county was organized. A few days before the Indian outbreak Enos started up the river with three men--John Klevinger, a Mr. Huntley and a third man whose name I do not recall. In a day or so he returned and reported that he and his companions had been attacked by Indians and he alone had escaped. The men were never seen again. He reported also that two or three miners living in Rogue River at Big Bend had sent him down for ammunition and he was given all the powder and lead he could carry. With the ammunition he immediately joined the Indians and became their chief. He was never in the fort or within musket shot of it during the war. Every day during the siege he could plainly be seen by those in the fort, riding a white horse, leading the Indians and urging them to attack. Tichenor states that Enos was arrested, put in irons and taken to Astoria and after a court-martial found innocent of wrongdoing. Enos was never taken to Astoria in irons, but after the war was over and the Indians had surrendered to the whites, he made a long detour through the mountains and appeared on a reservation in Washington Territory (now state). He was arrested there and put in jail at Portland. Sheriff Riley of Curry County made the trip from Port Orford to Portland by steamer, and after an adventurous return trip arrived at Port Orford with Enos, ironed hand and foot. Enos was tried by a court of law at Port Orford. No witness appeared against him, and Sheriff Riley was ordered to turn him loose. While the rivets which held the shackles on his ankles were being cut by a blacksmith a large crowd gathered outside the door. As soon as he was freed he was seized, taken up on top of Battle Rock and hanged--a fate he richly deserved--but not by a band of ruffians. He was hanged by citizens and miners who had been through the war and knew of his treachery. Another erroneous statement is that Ellen Tichenor, daughter of Captain Tichenor, found her way up on Battle Rock and there clung to the feet of Enos and begged for his life. No such incident occurred at the death of Enos. Sometime later when several Indians, identified by Mrs. Geisel as having taken part in the killing of her husband and sons, were hanged, some girl, probably Ellen Tichenor, did plead for the life of one of them. WALTER

F. RILEY.

TROUBLE BLAMED TO WHITES

Curry County Pioneer Returns to Defense of Indians.

PORT ORFORD, Or., Nov. 10.--(To the

Editor.)--My old

friend, Walter Riley, takes exception to my defending the Indians of

Curry County, especially Enos. Mr. Riley's people arrived in Curry

County in 1855. My grandfather, William Tichenor, came to Port Orford

in 1851; his family in 1852. My mother and her father and mother came

to Port Orford in 1853. My mother is living and is the oldest living

pioneer in that section of Oregon. When my mother tells me that Ellen

Tichenor was on Battle Rock pleading for the life of Enos, I will take