|

|

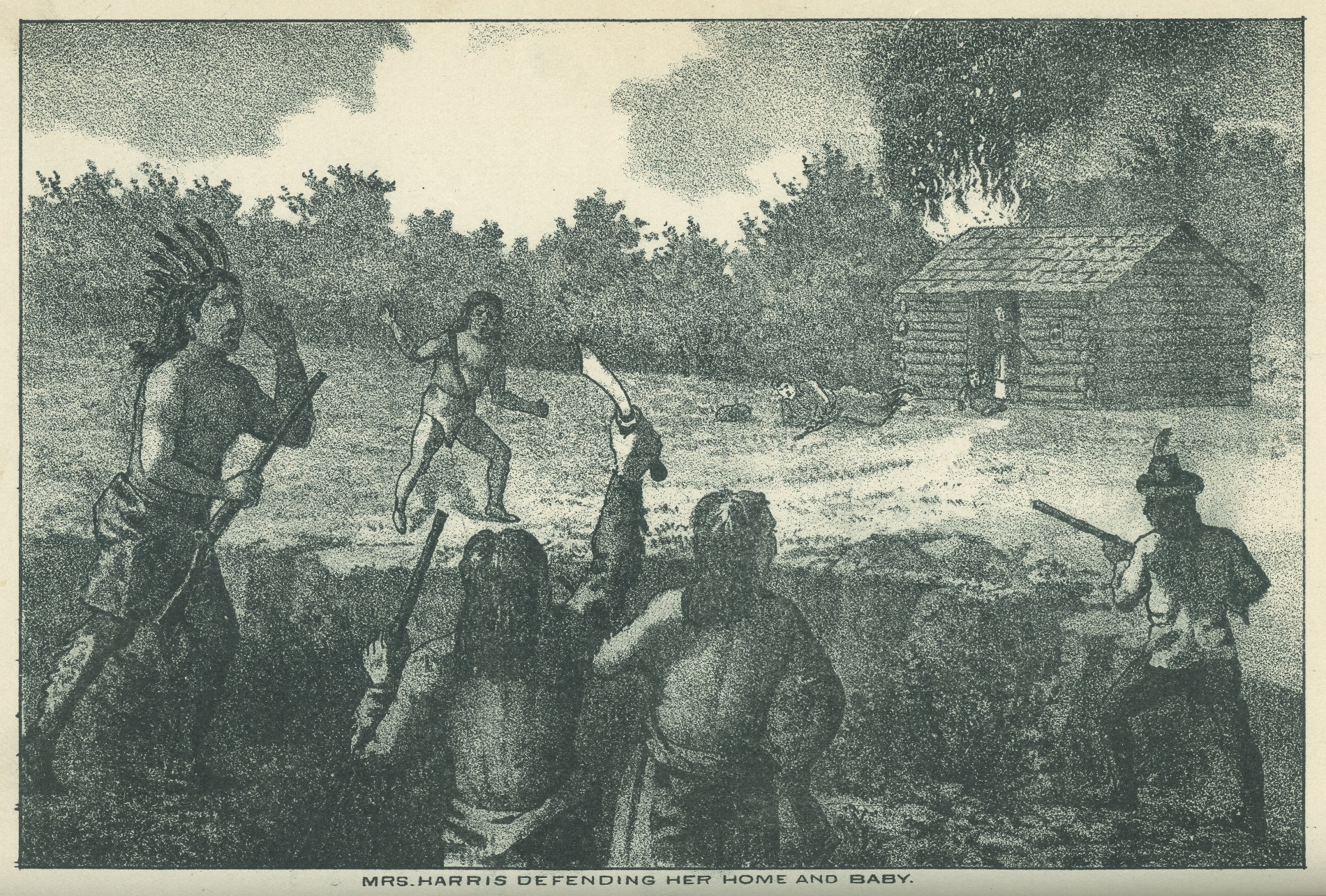

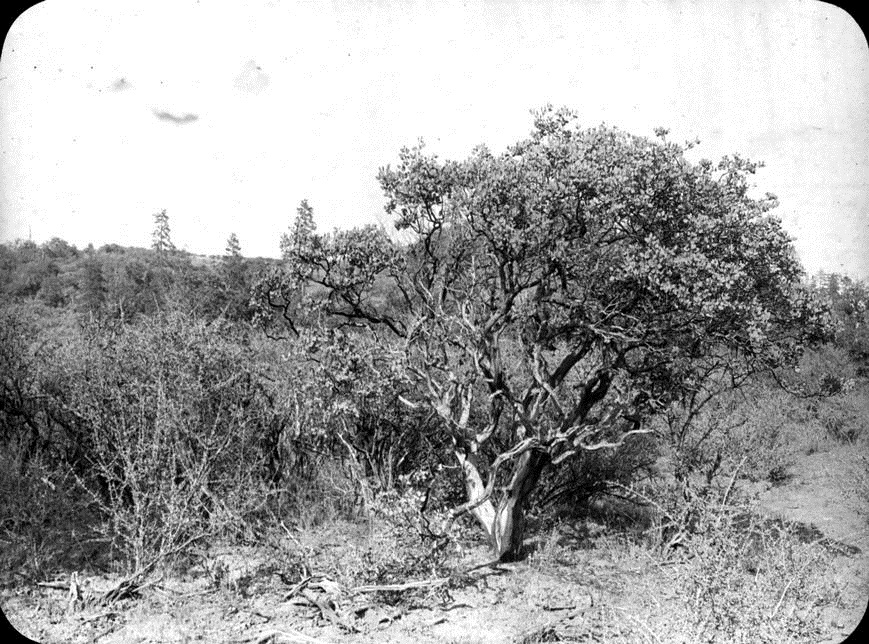

Mrs. Harris Note the contradictions. The first account below, from Mary Ann's lips and printed just a few days later, should be the most accurate--but new details kept being added.  Imagining the scene at the Harris cabin, from Reminiscences of an Old Timer, 1889 At about 8 or 9 o'clock of the morning of the 9th of October, 1855, as her husband was engaged in making shingles near the house and she was washing at the back of the house, he suddenly entered with the axe in his hand much alarmed, the house being surrounded by Indians, whose countenances and manner indicated that their intentions were not good. He seized his rifle, but in endeavoring to close the door was fired upon by them, the ball taking effect as before stated. Mechanically he discharged the gun twice at them, as she believes with no effect, and passing across the room fell upon the floor. The daughter in the excitement of the moment rushed out the front door, where she was shot through the right arm between the shoulder and elbow. The husband, reviving, encouraged his wife to bar the doors and load the guns of which there were a rifle, a shotgun and two pistols and revolver and holster pistol. She replied that she never loaded a gun in her life. He then proposed to give them presents to induce them to leave; she replied it would not answer, upon which he instructed her in the manner of loading the guns, and shortly after expired. She now was left entirely dependent upon her own efforts--her husband dead--her daughter severely wounded. Not discouraged, she commenced a vigorous discharge upon the savages, who were endeavoring to fire the house, having already burned the outbuildings. She thus continued to defend herself and daughter, she watching at one end of the house and the child at the other, for eight hours, and until about sundown, when the savages, being attracted by a firing on the flats about a mile below the house, left to discover from whence it proceeded. She embraced the opportunity and fled to a small, isolated thicket or chaparral near the house, taking with them only the holster pistol. Having barely secreted themselves before the Indians again approached the house, but finding it abandoned, they commenced scouring the thicket, about 18 in number, all armed with rifles. Upon their close approach she discharged the pistol, which produced a general stampede. This was repeated several times and always with the same result until finally surrounding the thicket they remained till daylight. Her ammunition was now exhausted. She heard the approach of horsemen, at which the Indians became alarmed and concealed themselves in the rear of the thicket. She, discovering the horsemen to be whites, rushed out towards them, but they had advanced so far beyond that they did not discover her. They were the advance of the volunteers. Concealing herself again with the empty pistol in hand, the main body soon approached, when the savages precipitously fled. Mrs. Harris having sent her little son, 10 years of age, to a neighboring house the evening previous, has not since heard from him, but he is supposed to be murdered. Also Frank Reed, the partner of Mr. Harris, is supposed to have been killed. This party of Indians escaped to the mountains. The company proceeded as far as Grave Creek, where all was quiet, and it was deemed unnecessary to remain, and they accordingly returned this morning, both men and animals completely exhausted. J. G. Woods, "Rogue River Correspondence of the Statesman," Oregon Statesman, Corvallis, October 20, 1855, page 2 They then came on to Mr. Harris', and shot him as he stood in the door, he falling into the house, and they also shot a little girl standing near him in the arm. Mrs. Harris drew her husband into the door--Mr. H. rose to his feet, took his rifle and fired at the Indians twice, killing one and wounding another, and fell dead. She then took the rifle, loaded it, and as an Indian advanced toward the house with his burning torch, she fired, and he dropped his torch and fled. She continued to load and fire during the day, until she had exhausted her last load of powder, when she was fortunately relieved by the Jacksonville volunteers, who fought the Indians the next morning (Wednesday), killing six, and losing one man. A. G. Henry, letter of October 12, Oregon Statesman, Corvallis, October 20, 1855, page 2 On proceeding to the house of Mr. Harris, twenty-four hours after the attack, the owner was found dead, and a party of Indians surrounding a thicket of brushwood. The Indians immediately fled, when from the thicket, to the joyful surprise of all present, emerged Mrs. Harris bearing in her arms her wounded child. It seems that Mr. Harris was killed at the outset by an Umpqua Indian. Before dying, however, he showed his wife the manner in which to load the rifle, she being wholly unskilled in the use of firearms. With this and a revolver she kept possession of the house for twelve hours. Her little girl, though seriously wounded, kept a constant lookout through the apertures of the ceiling, and reported to her mother from time to time of the near approach of the enemy. Night coming on they retreated to the thicket, destitute of bullets, yet notwithstanding they kept up an incessant fire with powder alone, up to the moment of her rescue. Thus did this heroic woman keep at bay twenty-five or thirty bloodthirsty Indians for the space of twenty-four hours, and that too without a morsel of food or even a drop of water. Weekly Oregonian, Portland, October 27, 1855, page 3 Organized a scouting party of fourteen, and started south. . . . searched for Harris' little boy (in my last [letter] I stated that Haines' boy was seen running through a field towards the woods--it was Harris' boy); could not find anything that could give us any clue of him. Passed on to Harris'; the floor and casing of the door were bedaubed with blood; Mr. Harris' pants were hanging against the wall, completely covered with clotted blood. The Indians attacked Harris' house on Tuesday morning, Oct. 9; Mr. H. was shot directly at his back door; as he was falling, Mrs. H. caught him and pulled him into the house and barred the door. A girl of Mr. H., fourteen years of age, was shot in the arm by a pet Indian who had been living about Turner's, called Umpqua Jack. There is two bullet holes in the door where Harris was shot. Mrs. H. and the little girl defended the house all day, and at night hid themselves in the bushes; they were taken to Jacksonville by the soldiers. Mr. H.'s old house, in which was a quantity of grain, was burned down. Edward Sheffield, Weekly Oregonian, Portland, October 27, 1855, page 3 Mr. and Mrs. Jones were killed; they lived this side of Wagoner's, also Mrs. Harris. After Mr. Harris was shot Mrs. Harris took the old gun and continued the defense by shooting between the house logs. She fired sixty-four times aided in getting means by her little daughter, until at last she ran to the yard, pursued by an Indian, who cursed her, knocked her down, and then shot her through the arm. She was left for dead. Immediately however she rose, ran to a ravine nearby and fell into it, where she remained. The Indians gave her up for dead, and turned their attention to the house. She was finally rescued by Major Fitzgerald. See for particulars Statesman of Oct. 20, 1855. S. F. Chadwick letter to Joseph Lane, November 1, 1855, Joseph Lane Papers, Indiana University. Chadwick is confabulating the Harris and Jones stories. After traveling until nearly sundown [on November 2 , 1855], we encamped at a building which had been preserved from the general ruin by the heroism of a woman named Harris. After her husband had been murdered and her daughter wounded, she had made a desperate and successful defense by shooting at the savages from between the crevices of the log house. The traces of her bullets upon the trees, which had shielded the Indians, and the marks of the tragedy within the dwelling, were plainly visible. Soon after dark a small party under the command of Lieut. Allston, 1st Cavalry, arrived with the wounded and encamped. Captain Smith, with a few men, passed us on his way to Fort Lane. The length of our day's march was about fourteen miles. Lieutenant Henry L. Abbot, Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, Washington 1857, page 108 Woman Warrior

If we go back to November 3, 1855 (with Andrew Genzoli

and through the files of the Humboldt

Times) we'll encounter an Indian war, then told [with]

this story: "We clip the following extract from a letter published in

the Crescent City

Herald, written from the seat of war, in Rogue River

Valley. We are sorry that the correspondent did not give the full name

and former residence of Mrs. Harris, as such deeds in a woman will live

after 'sod grows green': When the Indians first appeared at the house

of Mr. Harris, Mrs. Harris, with a little girl, was in the house, and

judging from the savage looks of the visitors that their arrival boded

no good, she addressed an Indian whom she knew by the name of Umpqua

Jack with the words, 'Jack, you are not going to kill us, are you?' to

which he gave an evasive answer. Mr. Harris coming in the back door,

Jack shot him down, and another Indian shot the girl in the arm;

whereupon Mrs. Harris shut and barricaded both doors. Mr. Harris lived

long enough to instruct his wife how to manage the rifle, which she

used with effect among the assailants, shooting through the cracks in

the wall of the house from 9 o'clock in the morning till evening, when

she became alarmed at the idea of the Indians setting fire to the house

in the dark; watching an opportunity when the attention of the Indians

was drawn for awhile off to other events at a short distance, Mrs.

Harris, with her little girl, escaped into a neighboring thicket with a

revolver in hand, and an apron full of powder and ball. The Indians

returning afterwards discovered her flight, but she kept them at bay,

discharging her revolver when she suspected anyone to approach her

hiding place. About sunrise a party of volunteers came to the relief of

this heroic woman."

Oakland Tribune, November 9, 1952, page 218 On the next morning, Oct. 9, the war began, and the first woman or child met by Indians was killed. Seven Shasta Indians left the reserve at Evans Creek, after killing a young man employed on the reserve by the agent, and going down Rogue River they fired on the people at Jewett's Ferry, without effect. They proceeded on down the river to Evans' Ferry, where they fired into a party of white men encamped nearby, and killed one man. They proceeded then along the Oregon road, and killed all the travelers and inhabitants along the road to "Jumpoff Joe" Creek; among them Mrs. Jones and child and Mrs. Wagoner and child. At Harris', the last house, they met with a desperate resistance from Mrs. Harris. Her husband was shot in the door. Dragging him into the house, she barricaded the doors and he lived long enough to instruct her in the use of the rifle, and all that afternoon she kept them at bay. They went off in the evening, and fearing their return to fire the house in the night, she seized her wounded child and made her escape into an adjoining thicket, with her store of ammunition in her apron, and by firing with a revolver whenever the Indians approached her hiding place in the night, she kept them off till daylight, when she was relieved by Major Fitzgerald's command, who had received information of the depredations committed on the road the morning before, and had pursued them thus far. "Our California Correspondence," New York Herald, January 31, 1856, page 3 Passed Mrs. Niday's, but little damage. Mr. Bowdin's house was in ashes; searched for Harris' little boy (in my last I stated that Haines' boy was seen running through a field toward the woods--it was Harris' boy); could not find anything that could give us any clue of him. Passed on to Harris'; the floor and casing of the door were bedaubed with blood; Mr. Harris' pants were hanging against the wall, completely covered with clotted blood. The Indians attacked Harris' house on Tuesday morning, Oct. 9; Mr. H. was shot directly at his back door; as he was falling Mrs. H. caught him, and pulled him into the house and barred the door. A girl of Mr. H., 14 years of age, was shot in the arm by a pet Indian, who had been living about Turner's called Umpqua Jack. There are two bullet holes in the door where Harris was shot. Mrs. H. and the little girl defended the house all day, and at night hid themselves in the bushes; they were taken to Jacksonville by the soldiers. Mr. Harris' old house, in which there was a quantity of grain, was burned down. Letter of October 18, 1855 from Leland, Oregon, quoted in "The Very Latest," Albany Argus, Albany, New York, December 1, 1855, page 2

By the Yreka Union

of the 20th, we have further particulars of the diabolical acts of the

Indians in Rogue River Valley. After finishing their horrible work at

Mr. Wagoner's, they attacked the house of Mr. Harris. The Union says:--

"When they began to gather around suspiciously, an Indian who had

frequently stopped with the family and been kindly treated come boldly

into the house with a gun. Mrs. Harris said to him, 'You are surely not

going to help murder us?' The Indian answered 'No,' but almost

immediately raised his gun and shot Mr. Harris, who was just coming

into the door, through the body, inflicting a mortal wound. He fell

forward into the house. Just then their little girl, ten years old,

received a wound in the arm from a shot fired by one of the Indians

outside, as she ran into the house. This left Mrs. Harris in a most

trying and horrible situation, and the heroic manner in which she

conducted herself surpasses any of the recorded cases of female courage

and fortitude which we have ever read. Her husband lay upon the floor

dying, and a large party of infuriated savages without stood ready to

rush in and finish the work of death. Mrs. Harris pushed the Indian who

had shot her husband out of the door and closed it after him. The floor

was covered with blood from the wounds of her dying husband and little

girl. Mr. Harris, before he expired, instructed her how to load a small

Allen's revolver. This she loaded and fired many times at the Indians,

which kept them some distance from the house. Night came, and she

watched for an opportunity to escape. The Indians withdrew out of

gunshot, to induce her to come out so they could pursue and shoot her

without danger to themselves. She took advantage of this and fled into

the brush with her little girl, taking the revolver with her. The balls

had all given out, but by continuing to load with powder and fire

whenever the Indians approached, she managed to keep them from charging

into the brush. The next morning a few mounted men came by, and she

called to them and the Indians retreated, and she and her little girl

were rescued from their perilous position."

On the first inst. I sent two Indians in whom I had confidence to the camp of the hostile party to endeavor if possible to get a correct statement in regard to the massacres of the 9th of Oct. last, and more especially to learn if they held in bondage any white women & if so to try to redeem them. They returned on the 11th inst. in company with two other Indians belonging to George's band with the following statement, that Old John & eight others [of] his own people did all the mischief that day until their arrival at Wagoner's ranch and at that place they killed Mrs. Wagoner & fired the house before they were observed by the other Indians. Chief George was camped within four hundred yards of the house, but was not at home himself; he had left the day previous to go to Cow Creek .Mrs. Wagoner's daughter, a little girl about eight years of age, was at George's camp and was saved by his woman concealing her. After John had killed these people, captured the teams & burned the houses, he was joined by some other Indians, among whom he divided the cargo that he had captured belonging to Peters & co.; about two thirds of George's people agreed to join him and all the Cow Creeks that were there did the same. The new force was then sent on the road to continue the work of pillage and death begun by Old John. He and his men here left for Illinois Valley. The house of Mr. Harris was then attacked by this new party. Mrs. Harris, who was rescued by Major Fitzgerald, recognized some Cow Creek Indians & talked to them before they killed her husband, which in a measure corroborates the statement made by the Indians. They both agree as to who shot Mr. Harris. I am not aware that the Indians knew anything of Mrs. Harris' statement previous to making their own. They also remarked they could have killed her but did not wish to kill women. They strove to take her prisoner, hoping her powder would soon become exhausted, when they would be enabled to capture her, from which they were prevented by the timely arrival of Major Fitzgerald. George H. Ambrose to Joel Palmer, February 18, 1856, Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 14; Letters Received, 1856, No. 98. The following letter we copy from the Lexington (Missouri) Express. Mr. Harris, as will be seen, was a native of this county, having emigrated to Missouri in the year 1841. He leaves many relatives and acquaintances in this neighborhood who will no doubt feel sad to hear of his untimely end. Wellington,

Lafayette Co., Mo.

Messrs. Editors:--By letters and papers from Oregon, recently received,

we have the particulars of Indian hostilities in Rogue River Valley.

Among the first victims of their savage fury was George W. Harris, who

with Rev. Jacob Gillespie, Wm. Cook and others emigrated from this

county to Oregon in the spring of 1852. Mr. Harris was a native of

Jefferson County Virginia, from whence he came to Missouri in 1841. His

wife, Mary Ann, is the daughter of James Young, recently deceased, one

of the earliest settlers of this county. Her defense of herself and

child against the attack of the savages is one of the most remarkable

instances of female heroism and courage upon record--a struggle in

which she maintained a spirit and bearing worthy [of] the daughter of a

blockhouse settler--and should be handed down to posterity as an

example of bravery in woman, under the most trying and heart-rending

circumstances.Jan. 24, 1856. We attach the following, in Mrs. Harris' own language, as nearly as possible: "At about 8 or 9 o'clock of the morning of the 9th of October, 1855, as her husband was engaged in making shingles near the house and she was washing at the back of the house, he suddenly entered with the axe in his hand much alarmed, the house being surrounded by Indians, whose countenances and manner indicated that their intentions were not good. He seized his rifle, but in endeavoring to close the door was fired upon by them, the ball taking effect in the breast. Mechanically he discharged the gun twice at them, as she believes with no effect, and passing across the room fell upon the floor. The daughter, in the excitement of the moment, rushed out of the front door, where she was shot through the right arm through the shoulder and elbow. The husband, reviving, encouraged his wife to bar the doors and load the guns, of which there were a rifle, a shotgun and two pistols, a revolver and holster pistol. She replied that she never loaded a gun in her life. He then proposed to give them presents to induce them to leave; she replied it would not answer, upon which he instructed her in the manner of loading the guns, and expired. She now was left entirely dependent upon her own efforts--her husband dead--her daughter severely wounded. Not discouraged, she commenced a vigorous discharge upon the savages, who were endeavoring to fire the house, having already burned the outbuildings. She thus continued to defend herself and daughter, she watching at one end of the house and the child at the other, for eight hours, and until about sundown, when the savages, being attracted by a firing on the flats, about a mile below the house, left to discover from whence it proceeded. She embraced the opportunity and fled to a small, isolated thicket or chaparral near the house, taking with them only the holster pistol. Having barely secreted themselves before the Indians again approached the house, but finding it abandoned, they commenced scouring the thicket, about eighteen in number, armed with rifles. Upon their close approach she discharged the pistol, which produced a general stampede. This was repeated several times and always with the same result until finally surrounding the thicket they remained till daylight. Her ammunition was now exhausted. She heard the approach of horsemen, at which the Indians became alarmed and concealed themselves in the rear of the thicket. She, discovering the horsemen to be whites, rushed out towards them, but they had advanced so far beyond that they did not discover her. They were the advance of the volunteers. Concealing herself again with the empty pistol in hand, the main body soon approached, when the savages precipitously fled. "Mrs. Harris having sent her little son David, ten years of age, to a neighboring house the evening previous, has not since heard from him, but he is supposed to be murdered. Also Frank Reed, the partner of Mr. Harris, is supposed to have been killed." A correspondent of the Oregon Statesman says: "I shall be very much disappointed if Congress don't grant the heroine, Mrs. Harris, a handsome pension, within twenty-four hours after the news reaches Washington. If they don't, the people of Oregon will." We have just learned that John Gillespie, son of Mr. George Gillespie, of this county, has been killed. Shepherdstown Register, Shepherdstown, [West] Virginia, February 23, 1856, page 2

Female

Courage.

Dr. McGill, of this city, handed us a

letter from Oregon yesterday, directed to himself, from which we make

the following extract relative to the heroism of a woman in that

territory. The writer in alluding to the Indian war says:"One Mrs. Harris fought the Indians about twenty-four hours. The Indians attacked Mr. Harris' house in the morning, and he soon received a fatal shot, and his daughter, about twelve years old, was shot in the arm. Mr. H. fell by the side of his wife. She had a pair of holster pistols, and kept up a regular fire at the Indians for several hours. They became alarmed and left. Mrs. Harris then attempted to make her escape with the child, and had left the house, when the Indians again made their appearance. She fled to a neighboring thicket, and commenced firing again, and kept it up till next morning. Just as she had shot away her last load, the Indians became alarmed, and started off, when to the happiness of the woman, some volunteers came, drawn thither by the firing. They pursued the Indians, and chased them to the mountains, killing three of their number. Mrs. Harris and daughter made their escape, but she witnessed the flames of the building which consumed the body of her husband. I could relate other feats of female bravery equaling this. But enough for the present." Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana, February 23, 1856, page 2 Mrs. Harris. An Incident of the

late Indian War in the North.

It was on the 9th of October last, about 9 o'clock in the morning, that

the Indians made an attack upon the house of Mr. Geo. W. Harris, about

thirty miles from Jacksonville, on the road to Northern Oregon. Mr.

Harris and wife, with their little daughter, 12 years of age, were the

only persons at the house, their little son David having gone about

half a mile distant to a field. When the Indians approached and were in

the yard, to the number of about twenty, they fired two or three shots,

one of which passed through the door and struck Mr. Harris in the

breast, which caused his death in less than an hour. The little girl

ran downstairs and to the door, where her father was lying shot.

Several shots were fired by the Indians, one passing through the little

girl's arm, but without breaking the bone. Mrs. Harris closed the

doors, and was advised by her dying husband to fight until she was

killed--not to be taken prisoner. The little girl, Ann Sophia, then

went upstairs, her wound bleeding profusely. Mrs. Harris had two guns,

one a rifle, the other a double-barreled shot-gun; also, two pistols,

one a six-shooter, the other a single barrel. She commenced firing at

the Indians through the cracks of the house, but thinks she did not at

first hit any of them. Her husband soon expired, and her daughter being

badly wounded and bleeding, was unable to afford her any assistance for

some time. The Indians, having taken all the horses out of the barn,

set fire to it, as well as the outhouses, and were making desperate

efforts to fire the dwelling house also. Mrs. H. still kept up her

firing, though it is impossible to tell the number of shots she fired,

as she has no recollection, only that she fired from the hour of the

attack until late in the evening. During the day, the Indians made a

parley, running some hundred yards from the house, which enabled her to

examine her little daughter's wound. At that time, or before, there is

no doubt but they murdered her little son, David, only ten years of

age, who, as before stated, was some half a mile distant at the time of

the attack.In the evening the Indians drew off, not able to approach the house on account of her continuous fire--having burned everything except the dwelling house. Mrs. Harris and her little daughter left the house and crawled into a very thick brush of willows, immediately by the roadside, and remained there during the night. Next morning she saw several Indians, but they did not discover her. When the attack was made by Major Fitzgerald and his command on the Indians at Wagoner's, she heard the report of the guns, and knew, she says, that a battle was going on. In a short time she saw the volunteers approaching, but still preserving her self-possession, she remained in her place of concealment until no doubt remained that those approaching were whites, and her friends. Mrs. Harris is the daughter of James Young, formerly of the state of Tennessee, she was married to Mr. Harris in Lafayette County, Missouri. Emigrated to Oregon in the year 1852. She is a relative of that well-known and celebrated pioneer, Ewing Young, who died in Chehalem Valley, Yamhill County, in this Territory, in 1843. Well might Gen. Lane say that he would ask for a pension for this noble-hearted, patriotic lady. She is not a heroine of a lauded romance, but the heroine of a hard-fought battle, wherein she saved the life of herself and daughter, by fighting over the corpse of her husband. She merits the undivided sympathy of a nation's gratitude--by bestowing upon her and her little daughter a pension for life.--Table Rock Sentinel. Trinity Journal, Weaverville, California, June 21, 1856, page 2 A. F. Hedges Superintendent &c. Oregon Territory Dear Sir Enclosed I send you the claim of Mrs. Mary A. Harris. Be pleased to acknowledge the receipt and if any error or omission occurs please also to inform me and suggest the remedy and much oblige. Respectfully

yours

JacksonvilleW. G. T'Vault atty. for Mary A. Harris Oct. 7th 1856 Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 14; Letters Received, 1856, No. 325. Jacksonville,

O.T.

Sept. 30th,

1857.

Dear General,In one of your eloquent vindications of our people during the last session of Congress, I remember a reference to Mrs. Mary A. Harris of our county, eulogistic of her noble self-devotion in defense of her dying husband and her wounded daughter, at the same time expressing an intention on your part to endeavor to obtain for her a pension from the general government. In furtherance of this laudable design, I am induced to inquire if it might not be advisable to prepare a memorial to Congress, during the approaching session of the assembly, in behalf of the widows and orphans left destitute. There are many such among us, who deprived of the support and protection of a manly arm, are reduced to the humblest drudgery and toil for a subsistence, and though sharing largely in the sympathies and kindness of the communities by which they are surrounded, are, in many instances, quite destitute. They who have lost more than the world can again return to them--the companions of life's early joys and sorrows, many of whom fell in the front of battle, where brave men, the pioneers of our nation, upheld our country's flag--have a right to expect the only recompense a grateful land can give--the pittance of a support. Mrs. Harris, to whom you made reference, is at present a resident of our town and earns a meager support for herself and daughter by "taking boarders." Her daughter has never fully recovered the use of her wounded arm and is unable to perform any arduous manual service. There are several other unfortunates suffering of this class in our vicinity, all of whom are in great need of a generous provision from our government. Many of these brave women furnish rare instances of heroic sacrifice and self-devotion, and if the Trojan mothers were worthy of our administration and fit subjects of historic eulogy, the deeds of these noble matrons are not less so. In the lofty devotion of Mrs. Harris are displayed the finer attributes of humanity--Attacked in her home by a numerous band of savages and armed with a rifle, for nearly twenty-four hours she held her assailants at bay. The fears of the woman were merged in the devotion of the wife and the mother, till even the savage foe shrank back before the pale, determined brow and flashing eye of that noble woman. Through long and weary hours she stood the defender of her dying husband and her wounded child, and only in the hour of rescue came back to her heart the tide of anguish which nearly dethroned her reason. But you will pardon my extended and verbose epistle. I had only intended to briefly consult you in regard to the expediency of a memorial, and to assure you that all efforts in furtherance of this laudable design will be gratefully acknowledged, not only by the recipients of any favors your efforts may bring, but by the unanimous sentiment of the entire community. Answer soon-- With a sincere appreciation of your many good qualities of head & heart permit me, sir, to subscribe myself, Yours Very Truly H. H. Brown Hon. Jos. Lane Joseph Lane Papers

CAPSIZE OF THE KERBYVILLE

STAGE, AND MOST FORTUNATE

ESCAPE OF THREE YOUNG

LADIES.--As

the Kerbyville stage was descending the hill coming into Jacksonville

Wednesday evening, with Misses Julia and Emma Hoffman and Miss Sophia

Harris, passengers, one of the lines extending to the leaders broke,

leaving but one line and the stage rolling down a steep hill at a

tremendous pace. At that time a person passed before the horses with a

load of brush, causing the horses to leave the road; the excellent

trusty driver, Mr. W. N. Ballard, spoke to the young ladies, telling

them, if possible, to jump out and leave the stage. Miss Julia Hoffman

and Miss Sophia Harris jumped out, landing on terra firma without

serious injury, leaving little Miss Emma in the stage, where she

remained until the stage capsized, and the horses broke loose, when she

made her appearance from the rear part of the stage, receiving only a

slight scratch on the arm, and was not the least frightened. This was a

miraculous escape; Mr. Ballard's presence of mind and experience no

doubt contributed to save the young ladies from injury.

We cannot tell whether there was danger and romance enough to make a hero and heroine of the whole affair, yet it was a runaway, a capsize, a promenade and, much to the satisfaction of all parties, little or no injury. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville,

July 23, 1859, page

2

Aaron Chambers, an old settler of Rogue River Valley, died on the 14th inst. His widow, says the Sentinel, has her full share of affliction. She saw her first husband, Mr. Harris, murdered by the Indians in this valley. On the same dreadful night her little son disappeared and was never heard of. Two years ago, her son-in-law, John Love, died; and last winter her only daughter, Mrs. Love, and one of her grandchildren were carried off by the smallpox. She is now left alone with three remaining grandchildren. "Oregon," Morning Oregonian, Portland, September 22, 1869, page 3 One cabin [the Haines cabin] which we examined contained three dead people, the man lying on the threshold and two children behind the bed, murdered by savages, while the mother was doubtless taken for a worse fate. A widow, Mrs. Harris, emerged from the bushes near her own house, which she had defended with shotgun the day previous, bearing in her arms her little daughter, shot through the arm. "Indian Troubles in Oregon, 1854-5" [sic], The Overland Monthly, April 1885, pages 420-422. The index credits the article to "J.G.T.", the text to "I.G.T." Usually attributed to Joel G. Trimble. The spring of [1855] Mr. Bates sold out and then McDonough Harkness was my partner the forepart of Oct. that year. I went to Roseburg for supplies for the Grave Creek House with the pack train of 12 animals. An Indian called Grave Creek Jack rode the bell horse for the train. Himself & sister Lucy had lived at our house nearly all summer. They were well treated, Lucy & Sophia Harris that was there then becoming bosom friends. (This same Indian Jack is the one that shortly afterwards shot Sophia & her father George W. Harris.) James H. Twogood, 1886, Silas J. Day Papers, Lilly Library, Indiana University

Those

[Indians] who were foremost in the attack at Wagoner's, Jones',

Haines', Harris' and so on, were well known to these families, had been

in their service from time to time, and had often received favors and

kindness when out of it. . . . At Harris' . . . they were suspected

before they could get possession of the house, and, consequently,

succeeded in killing only three out of the five they intended. Mr.

Harris received a fatal blow at the first fire; but, falling partially

into the house, his wife and daughter (the latter severely wounded)

succeeded in drawing him inside, and barring the door so successfully

as to keep the Indians out. While dying, Mr. Harris instructed his wife

how to load and use the rifle, and bade her defend herself to the last,

an order which she most heroically obeyed. For nearly twenty-four hours

she defended herself against the besiegers, and was then rescued by

some volunteers from Jacksonville. Master Harris and Mr. Reed were in a

field close by when the attack was made, and both fell victims to the

enemy.

Benjamin Franklin Dowell, The Heirs of George W. Harris and Mary A. Harris, Indian Depredation Claimants vs. the Rogue River Indians, Cow Creek Indians, and the United States, 1888, page 13 INDIAN DEPREDATION CLAIMS.--Among the Indian depredation claims examined by the Interior Department and recommended paid by the government are the following, made by persons of Jackson County. Mary A. Harris, house, wheat, etc., October 9, 1885, $3862: $1888.50 allowed.--Tidings. Excerpt, Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, March 8, 1888, page 2 HEIRS OF GEORGE W. HARRIS.

The

Select Committee on Indian Depredation Claims, to whom was referred the

bill (H.R. 2829) for the relief of the heirs of George W. Harris and

his wife, Mary A. Harris, and their daughter, Sophia Love, deceased,

submit the following

report:SEPTEMBER 14, 1888.--Committed to the Committee of the Whole House and ordered to be printed. Mr. HERMANN, from the Select Committee on Indian Depredation Claims, submitted the following R E P O R T: [To accompany bill H.R. 2829.] We, your committee, find that the original claimant, Mary A. Harris, was the owner of the property described, and from the proof submitted believe the same to be of the cash value at time and place of depredation of the sum of $3,862; that said Indians were in hostilities at said time and were of the tribe of Rogue River Indians; that said destruction of property occurred in Jackson County, Oregon, in 1855; that the husband of said Mary A. Harris was George W. Harris, and was massacred at the same time by said Indians. They were reputable people. The witnesses, several in number, are credible people, and some were participants in the defense of the country, and knew the marauding Indians, as well as the property taken, and claimants as well as George W. Harris and Mary A. Harris. The property destroyed consisted of a comfortable dwelling and all the household property and farming implements, cattle, and horses. No part was ever recovered and none ever paid for. We recommend payment of said sum of $3,862. Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fiftieth Congress, 1887-88, Report No. 3458 THE LOST CHILD.

The following narrative was written several years ago

by William M. Turner, for many years editor of the Jacksonville, Oregon

Sentinel, and

an old and highly esteemed resident of Jackson County. The tragic

incident so pathetically related by Mr. Turner is yet fresh in the

memories of the old pioneers of Southern Oregon:

It happened in early life. A heavy cloud had been gathering over the settlers in Southern Oregon. The fame of the lovely valley lying under the snow-capped Siskiyous, threaded by sparkling streams, covered with luxuriant grasses, the hiding place of antelope and deer, surrounded with hills that were yellow with gold, had attracted attention, and immigration had poured fast into the Rogue River country from California and Northern Oregon. It was the old frontier story--the white was crowding the red, and the latter was sullen and out of temper. Although the government had established a reservation in Rogue River Valley and made fair provision for the Indians, he was jealous of the encroachment of civilization, and his discontent was manifested by the occasional murder of a prospector or white traveler. At last the cloud burst, and it swept over the outlying settlements like a whirlwind of death. Murder by prowling bands of Indians had become so frequent that the patience of the whites was exhausted. A company of volunteers had been quietly organized, and on the 8th day of October, 1855, they struck the first blow on a large band of Indians who professed the utmost friendship for the settlers. Those who survived the slaughter hastened to the reservation and persuaded the few who were remaining there to join, commenced their work of retaliation at that point, and then striking down the river continued it in their flight, and did it fearfully well. It is at this point our story commences. In July of the same year George W. Harris, with his family, consisting of his wife and daughter about 11 years of age, and a bright, manly boy of nearly 9, had come from the Willamette and settled in a little valley through which passed the main line of travel, lying about forty miles north of Jacksonville. Mr. Harris was a worthy, industrious citizen, building a home for his family, who were happy and contented with the little spot where their weary feet had found rest. The house, a log building, was beautifully situated on a slight [illegible] in the Rogue Valley and on every side except the south the ground was clear and open. Mr. Harris had felled several trees in the vicinity of the house, and on the morning of Oct. 9th was busily engaged in making boards from one of them, not having the slightest apprehension of immediate danger. The October morning had dawned beautifully on the peaceful home. The throats of the songbirds were bursting with melody as the rising sun bathed the hills with mellow light and streaked the eastern horizon with gold and purple. Slowly the shadow of the tall pines crept down the western mountains as the morning wore on and the unconscious victims little dreamed that other shadows were falling in that mellow sunlight like cruel, hateful things on the brown sward of the little valley. Under cover of a large copse of willow just out of range, a band of fifteen or twenty warriors, with the warm blood of the murdered Wagoner family, who lived two and a half miles to the southward, yet undried on their brown hands, stole silently, stealthily toward the doomed home. Some of the fiends were probably half crazed with liquor, obtained at the Wagoner ranch, and pressing too eagerly for a favorable position for the attack, which was made at nine a.m., were evidently discovered by Mr. Harris. Leaving his work he walked rapidly into the house, and setting his ax in a corner of the room he took up his shotgun without saying a word, stepped to the door and endeavored to close it. Little Sophia accompanied her father to the door, looking in his face in a wondering, half-frightened way, but asked no questions, and just as they reached the door the Indians poured a volley of at least a dozen shots into and through it. Mr. Harris was struck fair in the breast by a rifle ball but stood firmly until he had discharged both barrels of his heavily loaded gun; then staggering backward he fell, never again to speak to those who so sorely needed his protection. The daughter was shot through the left arm by the same volley that mortally wounded her father, but the brave little maiden uttered no cry nor showed the slightest sign of pain, but bleeding freely ran upstairs and threw herself on the bed. It was now that the courage of the woman, that splendid quality that turns the fibers of the most delicate hearts to cords of steel, that mocks the valor of the sterner sex, was sorely tried. Mrs. Harris had observed her husband's movements, understood them, and at once realized the situation. For a moment only was she appalled. Instantly recovering her self-possession the brave frontier woman took the weapon from the grasp of her dying husband, closed the inner door, and rushing upstairs seized an "Allen" revolver lying on the roof plate and discharged it rapidly in the direction of the assailants through a hole in the chimney. The act doubtless saved her life and that of her daughter, for the Indians, who had made a second rush, shrank back under cover of a large pine tree which stood about twenty paces from the door, not knowing that the house had but a single defender. Fortunately Mr. Harris had prepared a large number of cartridges for a possible emergency, and perfectly familiar with firearms, his wife commenced loading and firing toward the tree, which was afterward found to be scarred with bullets. Changing her position from up to downstairs, always keeping one barrel in reserve, and carefully guarding all approaches to the house, Mrs. Harris kept up a steady fire for hours, and the Indians must have been convinced that the house was full of armed men, for they never exposed their cowardly forms. They returned the fire, however, sending their bullets through the chinking of the house, filling the room with splinters, but without effect. Just at two o'clock the Indians drew off in a body, striking toward the Haines ranch about a mile to the westward, where they soon did some bloody work. Their retreat took a load from the mother's heart. Strung up to its utmost tension for five long hours that seemed ages, it now relaxed, and she who had fought like a tigress for her offspring was now herself but a sobbing child. Was it strange that the mother's heart should be bursting? Trickling through the floor above were drops of blood, and Mrs. Harris ran wildly upstairs. Little Sophia, with her lips pallid from the loss of blood, was lying on the bed in a fainting condition, and her mother learned for the first time that she had been wounded. Carefully bandaging the wound and applying restoratives, her next thought was for little David. Just before the attack the little fellow had accompanied Samuel Bowden, who lived about a quarter of a mile north, to his home, and as neither made their appearance the mother feared that they, too, had fallen victims. Anxiously she waited, patiently she listened, and evening fell and still the child came not; and as she watched and listened in vain, the mocking winds among the pines seemed to say to the poor throbbing heart: "No more forever." Evening came and a new danger threatened. Should the Indians return they could steal to the house under the cover of darkness and fire it with perfect safety, and Mrs. Harris determined on flight. Taking Sophia in her arms, and with a sad parting look at the white face of him who had given his life for them, she silently stole from the house and hid in the chaparral. Who can write the memory of that dreadful October night? Who can tell the anguish that wrung the heart of the heroic woman? As the night wore on the sky grew higher and the stars grew colder; still they looked coldly down on her as she kept sleepless watch--holding in her arms the faint and bleeding child--the only pleasure left her on earth. Now and then the stealthy footsteps of a coyote were heard quite close to the hiding place of the fugitives. Approaching within a few feet, one of them had smelled the blood with which little Sophia's garments were saturated, and it set up that peculiarly dismal howl that only a prairie wolf can make. From point to point it was answered by others. From hill to hill the howl gathered and rose and swelled in melancholy cadence on the cold night air till the bereaved and stricken woman feared they would gather and tear her and her darling to pieces. Hours and hours passed by, but the stars seemed motionless. How that woman prayed for daylight, unmindful of the dangers it might bring. Her thoughts were now wholly absorbed by the probable fate of the handsome, bright-eyed child who had been so suddenly separated from them, and her anxiety was maddening torture. Could she have known that he had been killed outright it would have relieved the pressure on her mind, already overburdened with horrors. He might have escaped to hide and perish from cold and hunger, or be torn to pieces by the wolves; he might have been captured to undergo tortures indescribable, and when at last daylight broke it is only wonder that agonizing doubt had not driven the mother raving mad. Again the morning dawned beautifully; again the shadows of the tall pines crept down the hills; again the songbirds filled the little valley with melody, and still the anxious mother watched. Peering out carefully she saw an Indian in the brush who himself seemed to be watching, and she shrank back again under cover. Commanding a view of the house, she soon observed three persons boldly approach and break down the door. Supposing the savages had returned in force, Mrs. Harris now gave herself up as lost, and to add to her terror, it was scarcely a moment till a band of mounted warriors poured down the valley. But a second glance disclosed the fact that they were in flight, and she knew that succor was at hand. Scarcely were the Indians out of sight when her quick ear discovered the sound of heavier hooves thundering down the road from [the] south, and in a few moments a detachment of dragoons and a few volunteers under command of Major Fitzgerald were sweeping gallantly across the valley. On came the brave boys filled with vengeance, fresh from a battle at the ruins of the "Wagoner place," where they surprised and killed five of the Indians. On they dashed, still nearer and nearer, and Mrs. Harris recognized their uniforms when she ran with Sophia in her arms to meet them. Drawing rein suddenly, the boys gathered round the fugitives. Covered with blood and blackened with powder, worn and haggard with exhaustion, they were hardly recognizable, and the Major exclaimed: "Good God! Are you a white woman?" Closer the gallant fellows gathered to hear her simple story, quickly told, and more than one bronzed cheek was wet with tears that never shamed their manhood. The pursuit of the Indians was at once discontinued. After attending to the immediate needs of the survivors and burying the dead, Major Fitzgerald ordered a diligent search for the boy, but not a trace of him could be found. Subsequently the Major furnished Mr. Harkness with an escort of eight men for the same purpose. Every ravine, every hollow, every thicket for miles around the Harris place was carefully searched, but not even the child's wagon, which he had taken with him, could be found. Mr. Bowden, who fled toward Grave Creek on the first fire, stated that the little fellow started home before the attack, and the most careful examination revealed no trace of his remains in the Bowden house, which was burned. There was but one hypothesis: The child had been captured and carried away, but this was abandoned. During the war that ensued captive squaws and strolling bands of Indians were closely questioned, but they persistently denied any knowledge of the child. A year went by, and the remains of a man named Reed was found on the Harris ranch, and search was renewed for Davey but without result, and still the pines whispered to the sad and sorrowing woman, "Never! and never more!' Little Sophia, afterward the wife of John S. Love, one of the honored citizens of Jacksonville, was carried away by the fearful epidemic that scourged that town in 1869, joining her husband who had preceded her only a few months. The intrepid mother, who did a deed as brave as ever recorded in ancient song or story, became the wife of Aaron Chambers, and widowed a second time, lives among us honored and beloved. Mrs. Chambers often relates the story to her grandchildren, George and Mary Love, telling them how nobly their mother bore her share of the burden. Twenty-three years have passed, and often as the twilight deepens and the evening shadows gather, the mother sits sadly and silently with folded hands, looking down into the still-unburied past and wondering if in earth or sky she will find her second born. Who that has not suffered can tell the withering thoughts that cling to the bitter memory of that dreadful October day and night? And who among us all can say that when the great harvest of the Eternal is garnered in there will not be one little golden sheaf that will fill the sad and sorrowing heart with gladness for ever and ever more? Gold Beach Gazette, October 19, 1888, page 3. From Hanley scrapbook, SOHS M41D9. Fred Lockley also reprinted this account (below), in 1925, attributing it to a "legal brief" pamphlet by Turner. On reaching Wagoner's, they were joined by Chief George's band of Indians, who had been camped on the creek near his house for some months, always professing friendship for the whites. Early that morning, Mr. Wagoner left home to escort Miss Pellet, a traveling temperance lecturer, to Illinois Valley, leaving his wife and four-year-old daughter in perfect security, as he supposed, under the protection of Chief George, who had always been a favored guest at his house. Upon the arrival of the war party, Mrs. Wagoner and child were murdered, and the house burned over them. The barn and all the outbuildings were also burned. From this point they went to the house of George W. Harris, a few miles beyond. Mr. Harris was making shingles near the house, and Mrs. Harris was engaged in washing behind the house. About nine o'clock, according to the statement of Mrs. Harris, her husband hastily entered the house with an axe in his hand, stating that the house was surrounded by Indians, whose manner indicated they were warlike. He seized his wife, but while endeavoring to shut the door, he was shot through the breast by a rifle ball. He twice after fired his rifle mechanically and fell upon the floor. His daughter, eleven years of age, seeing her father shot, went to the door, when she was shot through the right arm between the shoulder and elbow. The husband, reviving, advised his wife to bar the doors and load the guns, of which there was a rifle, a shotgun, a revolver and three pistols. Mrs. Harris secured the doors, but told her husband she had never loaded a gun in her life. Mr. Harris instructed her how to load the weapons and expired. This brave woman, left to her own resources, commenced a sharp firing upon the savages, who, having burnt the outbuildings, were endeavoring to fire the house. She thus continued to defend herself and daughter, she watching at one end of the house and the child the other, for eight hours, and until about sundown, when the savages, being attracted by a firing on the flats about a mile below the house, left to discover whence it proceeded. She embraced the opportunity and fled to a thicket of willows, which grew along a spring branch near the house, taking with her only a holster pistol. She and her daughter had barely secreted themselves when the Indians, eighteen in number, all armed with rifles, returned, and finding the house abandoned, commenced scouring the ticket. Upon their near approach to her hiding place she fired her pistol, which caused a general stampede. This was repeated several times, and always with the same result until finally, surrounding the thicket, they remained till daylight. Her ammunition was now exhausted; but she retained her position until the volunteers arrived, when the Indians fled precipitately, and she was saved. Mrs. Harris had on the evening previous sent her little son, aged nine years, to the house of a neighbor. He was killed, as well as Frank Reed, the partner of Mr. Harris. This list does not include all who were murdered on that bloody day, many of whom were never heard of afterwards. Upon the receipt of the news at Jacksonville, at least twenty men sprang into the saddle at once. They did not wait to be enrolled, consequently a full list cannot be obtained; but among them were John Drum, Henry Klippel, James D. Burnett, Wm. Dalland, Alex. Mackey, John Hulse, Angus Brown, Jack Long, A. J. Knott, Levi Knott and John Ladd. Upon their arrival at Fort Lane, they were authorized by Major Fitzgerald to go in advance as a scouting party, stating that he would follow them with his company of fifty-five dragoons in a short time. The narrative of the expedition is copied from the diary of J. D. Burnett, one of the volunteers. He says: "We left Evans' Ferry at two o'clock on the morning of the 10th of October. The first body found was the body of Jones, whose body had been nearly eaten up by the hogs; the next were Cartwright and his partner, the apple men. As they neared the creek on which Wagoner's house had been situated, they found the Indians were still there. The volunteers crossed the creek, which was thickly bordered by willows, when they met about twenty Indians on horseback, drawn up in line of battle, with a battle flag. The Indians challenged the volunteers to fight, which was quickly accepted; but as the volunteers charged, Major Fitzgerald broke through the willows, and with his dragoons joined in the movement. The Indians suddenly retreated, but too late. Seven were left dead on the ground, and the number of wounded could not be ascertained, as the Indians fled to the mountains where the troops could not follow them, as their horses were already nearly exhausted. "Upon reaching the Wagoner house, Mr. Burnett and Alex. Mackey found the bones of Mrs. Wagoner and her little girl on the hearthstone. Taking some bricks from the chimney, they made a small vault, into which the deposited the remains with the intention of removing them upon their return and giving them decent burial. Upon their return, they found the Indians had taken the bones to a large pine stump near the house and crushed them to powder. Upon reaching Harris's ranch, they found Harris dead in the house, and soon discovered Mrs. Harris and her daughter coming toward them from a willow thicket nearby. The girl had been shot in the arm; and both were in a deplorable condition. After they had buried Mr. Harris, the company was ordered back to take the woman to a place of safety, and to gather up the dead. On the next day, they returned to take care of three wagons belonging to Mr. Knott, which were loaded with merchandise, but fund them all burned with their contents and the teams driven off. In searching the surrounding country they came to the house of Mr. Haines, where they found Haines and his young son killed; but Mrs. Haines could not be found. As she was never afterwards heard of, she undoubtedly met the fate of Mrs. Wagoner." Elwood Evans, History of the Pacific Northwest, 1889, pages 435-437 - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

MARRIED.

Married, in Jacksonville, Oregon, on the 23rd of February, by the Rev.

Mr. Williams, Mr. JOHN LOVE

to Miss SOPHIA HARRIS.

Pittsburgh papers please copy. This young lady was wounded during the

Rogue River War, in October, 1855, in an attack made by the Indians

upon her father's house; and in the fight which followed, her arm was

broken, and her father and her little brother were shot dead. The house

having been burned by the savages, she and her mother escaped to the

chaparral, each armed with a rifle, and defended themselves for

twenty-four hours against a body of twenty Indians, until rescued by a

party from Jacksonville. This sounds like the deeds of some of the

famous heroines of Kentucky and Tennessee, in the fearful encounters

with the savages by the early settlers. John Love, you've got a true

woman for a wife. As you are in name, so be to her in reality. She is a

girl every American ought to be proud of.

Daily Alta California, San Francisco, March 3, 1860, page 2 Born.

In Jacksonville, Nov. 19th, to the wife of John S. Love, a daughter.

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville,

December 2, 1865, page

2

ANOTHER GONE.--Mrs. John S. Love died this morning at 8 o'clock from smallpox, the most appalling of all human disease. She was a woman of inestimable worth, beloved by a large circle of acquaintances, and her death has made deep sorrow and gloom in this community. She leaves four little orphan children to mourn for a mother's smile and care, and to meet her again only in a brighter and better land. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, January 16, 1869, page 2 DIED.

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville,

January 16, 1869, page

2LOVE.--On the 16th,

Mrs. Sophia Love, relict of John S. Love, aged 25 years.

ANOTHER PIONEER GONE.--On Monday last, Mr. Aaron Chambers, one of the old pioneers of the valley, died after a lingering illness. Up to Saturday, he appeared to be improving; but from Saturday morning to the time of his death he sank gradually away. Mr. Chambers came here in 1852, and was much respected. His funeral was one of the largest that has taken place for many years. His widow certainly has had her full share of affliction. She saw her first husband, Mr. Harris, murdered by the Indians in this valley. On the same dreadful night, her little son disappeared and was never heard of. Two years ago, her son-in-law, John Love, died; and last winter, her only daughter, Mrs. Love, and one of her grandchildren were carried off by the smallpox. She is now left alone with the three remaining grandchildren, and it is to be hoped that she may be long spared to guard over them. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, September 18, 1869, page 2 DIED.

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville,

September 18, 1869, page

2CHAMBERS.--At his

residence, near Jacksonville, Sept. 13th, AARON

CHAMBERS; aged 69 years, 1 month and 1 day.

THE remains of Mrs. Chambers who died in 1859, were removed on Thursday from the farm to the cemetery on the hill. It was done, we believe, at the request of her son, Mr. West Manning, of this place. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, September 18, 1869, page 2 GONE TO HER REST.--Sorrowfully we note that Mrs. Mary A. Chambers, relict of the late Aaron Chambers, passed away at 4 p.m. yesterday after a painful illness of about a week from pneumonia in the 60th year of her age. This estimable lady was an early pioneer in this valley and will be remembered as the heroic woman who defended her home from an Indian attack near the historic Wagner ranch, in this county, when her first husband G. W. Harris was lying murdered at her feet. Her trials on that dreadful October day, when her little home was surrounded by yelling savages, stamped her as a woman of no ordinary character and the story of her bravery has passed into Oregon history as one of its most thrilling events. Mrs. Chambers was widely known and loved for her Christian virtues and gentle character. She has been a mother and faithful guide to her orphaned grandchildren, George, John and Mary Love, who now mourn their best friend on earth and one who was the type of all that is loving and true and gentle in humanity and whose work was so noble and well done; has surely laid down her cross for the rest and crown of immortality. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, February 18, 1882, page 3 Death of a Brave Man.

Democratic

Times, Jacksonville, January 16, 1890, page 3

John B. Hulse, who died at Pendleton recently, was born in Fayette,

Howard County, Missouri, in the year 1829, and came to this coast in an

early day, being an old pioneer. At the time of the Rogue River war

with Indians, John Hulse rescued Mrs. G. W. Harris and her little girl

from the clutches of the Indians after they had murdered her husband,

who lived long enough to show her how to load the gun. She kept the

Indians at bay until dark, and then, with the little girl, she made her

way to a little creek called Jumpoff Joe, and secreted herself and

little one from the Indians. Early in the morning she heard the sound

of horses' [sic]

feet, as did also the Indians, who thought the whites were coming and

took flight up the creek. The horseman [sic]

proved to be none other than John Hulse. Mrs. Harris at once recognized

him and shouted, "I am a white woman!" Hulse answered: "I am a white

man, come to take you away from here." He took the woman and child to

Jacksonville on his horse. Such is an example of the noble principle of

our departed friend, John B. Hulse.--[East Oregonian.

The cause of that battle [Hungry Hill] lay with a bunch of outlaws. They were whites, but they had acted in a way that would have disgraced Indians. They had killed, massacred thirty-five squaws, poor, helpless things who were camped on Bear Creek. So the bucks started on the warpath, no blame to them, but they killed a lot of good men instead of the outlaws. They made for the first white man's house they came to; it belonged to a man named Harris. It was a double-storied hewed house, pretty good for thereabouts. Harris and his wife and the little 2-year-old girl were at home. The woman, with the judgment that women have, tried to get her husband to stay inside; but no. he was going out to fight those thirty-five Indians. As he opened the door they shot him down, of course. The same fire that killed him wounded the little girl. Mrs. Harris picked up the child in her left arm; a pistol was grasped in the right hand. For two days and nights that woman stood off the Indians from her home and her baby, and was still standing them off when we advanced and took up their attention. That's the kind of stuff that women of the West were made of in early days. Walter S. Kitchen, "How I Came to Be in 165 Battles," San Francisco Call, October 13, 1901, magazine section page 1 We were riding along slowly, feeling about as tired as possible for men to get, when we discovered two horsemen coming toward us at full speed, each with a woman behind him. The horsemen proved to be Claus Westfeldt and Charles Williams; the women Mrs. Harris and her daughter Sophia, the latter wounded in [the] fleshy part of [her] arm, between the elbow and shoulder. The sight of these heroic women made us forget that we had been in the saddle 12 hours or fatigued or hungry. Westfeldt and Williams [who had ridden] in advance of [the] main column, found Mrs. Harris and daughter hidden in the willows and took them up on their horses. Mrs. Harris, after 36 hours' vigil and self-reliance, finding rescue an accomplished fact and after telling our boys that the Indians were at the house, then asked to be taken to a place of safety. As soon as they came up to our lines and reported the situation all of the volunteers and part of the regulars rode on to the house and surrounded it. The writer rode up to near the front door, jumped off his mule and pushed the front door open with the muzzle of his gun, and instead of Indians, saw Mr. Harris lying dead on the floor. We investigated further but found no Indians. Some of our men, who were in pursuit of the Indians, had to or did pass the house, stopped for a moment to inspect the premises and then continued to widow Niday's place. Mrs. Harris undoubtedly mistook them for Indians. "A Reminiscence," Henry Klippel, as dictated to Mabel Prim, photocopy of manuscript in Rogue River Indian War vertical file, Southern Oregon Historical Society. Written sometime between the 1899 death of Jane McCully and Klippel's in 1901. Published in the Medford Enquirer of February 2, 1901, page 4 [John W. Noah] was one of the troop who rescued the Harris family, when this family was surrounded by Indians. They were making a gallant defense at the time of the rescue. Mr. Harris, though wounded, was able to handle a rifle, and Mrs. Harris loaded the guns and helped to hold the savages at bay until assistance arrived. "Death of John W. Noah," The Plaindealer, Roseburg, December 30, 1901, page 1 A HEROIC PIONEER WOMAN

How Mrs. Marris Fought the Indians in [1856].

In the article which we publish in this issue telling

of the discovery of Crater Lake, Mr.

Hillman

mentions, in connection with the Rogue River Indian War, Mrs. Harris

and Mrs. Wagoner, and especially the heroism of the former.

The Harris place, at the time of the Indian war in 1855, was about seven miles northwest of the present location of Grants Pass. It is the same place which is now owned by Dr. W. H. Flanagan of this city and which lies about midway between Louse Creek and Jump-off Joe, on the wagon road, At that time the road ran on the other side of the place from here it does now, nearer the mountain, and the Harris dwelling was situated on this road. The Indian attack in this country was a complete surprise. The settlers were unprepared, and many of them were massacred in their homes. The Indians surrounded the Harris house and called Harris out of the house. As he stepped from the doorway they shot him. Mrs. Harris ran out and dragged him inside the house, where he died soon after. She and her daughter, a girl some 12 years old, took rifles [and] went upstairs, where they could command a view of all points, and with the heroic nerve which was possessed by so many of our pioneer women held the Indians at bay until nightfall. When darkness came on they escaped from the house and lay hidden all night in the willows which grew on the place. In the morning about nine or 10 o'clock a small company of volunteers appeared on the scene and they were rescued. The house was burned by the Indians. A boy living at the Harris home was absent on an errand to the neighboring place at the time of the attack. He was never seen afterwards, and it is supposed that he was killed by the Indians. Mrs. Harris later became Mrs. Chambers of Jacksonville, and the daughter was married to John Love of the same place. Mrs. Wagoner lived on Louse Creek, the place which is now occupied by G. M. Savage. Her husband was killed away from home either going to or returning from Jacksonville. [Wagoner was not killed.] She was taken prisoner by the Indians, and her fate was never learned. Rogue River Courier, Grants Pass, June 18, 1903, page 1 Death of Mrs. Mary H. Hanley.

On Tuesday of last week the death took place of Mrs. Mary H. Hanley at

the Hanley farm on the Jacksonville-Central Point road. Saturday

afternoon the services were held, first at the family residence, where

Rev. W. F. Shields of the Presbyterian church of Medford delivered the

discourse, and then at the Jacksonville cemetery, where the interment

took place and where the impressive burial service of the order of the

Eastern Star was carried out by Adarel Chapter No. 3 of Jacksonville

cemetery. Mrs. Hanley was a member of Reames Chapter of Medford, but

the members of that chapter were, through unavoidable circumstances,

unable to conduct the exercises, but a delegation from the chapter were

present to assist in paying a last tribute to their departed sister.

There was a large attendance of friends of the deceased at the

cemetery, and the floral tributes were many and both beautiful and