|

|

Rogue Valley Hangings There are a lot of myths about Jacksonville hangings. They were rare and few. Jackson Maynard or Robert S. Maynard or John Brown, May 10 or 16, 1852: A short time since, John Brown, of Illinois, became involved with a quarrel with another miner. Upon being called a liar he shot his antagonist, who died almost instantly. We have not been furnished with the name of the deceased. Brown was tried, sentenced to be hung, and was to have been executed on the 16th [sic] inst. "From Shasta," Sacramento Daily Union, May 24, 1852, page 2 I received a letter a few days ago from John Newsom at the Oregon mines. He states that a gambler shot a man there on the 10th [sic] of May last, and at the expiration of a week, the gentleman pulled hemp! David Newsom, letter of June 15 from Pleasant Valley, O.T., "From Oregon," Illinois Daily Journal, Springfield, August 9, 1852, page 2 May 29. . . . This may be called "mob law," but it is a government that seems to be necessary in these new settlements, where courts are not organized. Egress to the older settlements is so tedious and expensive that without such government crime would go unpunished, and there could not be order and safety. I understand this democratic surveillance has been deliberately prudent, and its effect salutary. A white man was given counsel, a fair trial before an impartial jury, and hung, for the diabolical murder of a white man. Another white man, for shooting--not mortally--an Indian, was made to pay five horses, ten blankets and thirty dollars, which satisfied perfectly the chief, the tribe, and the wounded Indian, and prevented retaliation. Nathaniel Coe, "The Territory of Oregon," The Ovid Bee, Ovid, New York, September 22, 1852, page 1 OREGON.--The Oregon Statesman of June 1st contains some items of interest. . . . Robt. S. Maynard, from Illinois, shot a man by the name of J. C. Platt, at Jacksonville, because he had been insulted by him. Maynard was tried by a court jury selected from the citizens, found guilty of murder in the first degree, and executed in three days after. Illinois Daily Journal, Springfield, July 31, 1852, page 2 Murder and Execution on Rogue

River.

A murder was committed at Jacksonville, a small mining village on Rogue

River, on the 2nd of May, under the following circumstances: A young

man named J. C. Platt, slightly under the influence of liquor,

challenged any person to run a foot race with him. Several bystanders

selected a man of the name of Robert Maynard, who went by the name of

Brown, to accept the challenge. Platt said he was no kind of a man, and

that he would not run with him; that he could beat him at

anything--fighting or anything else; and that if he ran, he wanted to

run against a man. Brown said he was insulted, and that he would shoot

Platt. He borrowed a revolver, and afterwards meeting Platt in the

street, told him he had insulted him. Platt denied having done so, but

said that if Brown was disposed to "take it up," he could do so, at the

same time taking off his coat for a fight. Hard words passed between

them; Platt said Brown was a liar and a thief; Brown forbade him

repeating it; the language was repeated, whereupon Brown drew his

revolver and shot him through the left breast. Platt exclaimed, "The

damn scoundrel has shot me--arrest him," and fell. He lived but three

minutes. Brown was taken into custody, and on the following Tuesday

tried. A judge and prosecuting attorney were appointed, and a jury

summoned, and a fair trial given him. He was defended by D. B. Brenan,

of Portland. An auctioneer, known by the name of "Tom Hyer," acted as

prosecuting attorney. The trial lasted twelve hours, when the jury

retired, and after deliberating an hour and a half, returned a verdict

of guilty of murder in the first degree. Brown was heavily ironed and a

guard of eight men placed over him. It was moved that he be allowed

three weeks to "make his peace with God." The crowd rejected this

motion by a large majority. It was then moved that he be allowed three

days to prepare for the change, which motion prevailed. Accordingly on

Saturday the 8th he was taken in a cart about one mile from town, where

a gallows had been erected, and hanged. He has been some time in

Oregon, and we learn spent the past winter at Marysville. He talked

freely upon the gallows; said he was not sorry for what he had done, on

his own account, but he was sorry to afflict his parents and brothers

and sisters. He said he should be hung and buried in that grave

(pointing to a grave nearby, which had been dug), and that the traveler

would point to it and say there lies a man who would not be insulted.

He bid the crowd "goodbye," and was swung off. He stated that his

relatives lived in Illinois. He was twenty-one years of age.

Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, June 1, 1852, page 2 LYNCHING ON ROGUE RIVER.--Mr. Henkle, of the Express, informs us that the man Brown, of Illinois, who killed John D. Platt, of Iowa, on Rogue River a few weeks since, has been hung. He received a fair and dispassionate trial at the hands of a committee appointed by the miners. Mr. Platt worked at his trade--carpentering--for several months in this place. He leaves a wife to mourn his sad fate, who in all probability is on her way to this country at the present time.--Shasta Courier. Daily Alta California, San Francisco, June 15, 1852, page 2 Notwithstanding the loose and reckless character of a large portion of the population, unrestrained by the refining influences of organized society, crime was remarkably rare. It is true there was no written law. The hastily prepared handful of territorial laws, borrowed from the Iowa code, generally relating to property rights, had hardly crystallized into shape, and were inoperative at so remote a point from the seat of territorial government, and where there was neither county organization nor judicial officers. But there was a law higher, stronger, more effective than written codes--the stern necessity of mutual protection--and a strong element had the courage and will to enforce it. Justice was administered by the people's court; its findings were singularly correct, its decrees inflexible, its punishments certain. In 1852 the first court of this character was convened. A miner named Potts was shot dead, without provocation, by a gambler named Brown. Immediately every claim was vacated. Men, not angry, but outraged by the dastardly deed, gathered in hundreds, and the assassin was secured. That fine sense of chivalry and fairness, common even on the frontier, prompted a proper investigation, and in the absence of even a justice of the peace, W. W. Fowler, now a resident of California, was appointed judge. A jury of twelve men was selected. The case was tried by the rules of right and wrong, divested of legal technicalities; Brown was clearly proved guilty of a cowardly murder, and taken to an oak grove, a little north of the site of the Presbyterian Church, hanged, and buried under a tree, a few yards west of where the church now stands, and the remains have never been removed. The court was quietly dissolved, the judge disclaiming the right to exercise further jurisdiction, but the lesson was salutary and effective. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 360 In 1852 there were no civil courts established in Jackson County except what was called an [alcalde's] or miner's court, which adopted the common law of the United States as to property, and the Mexican law as to life and death. . . . The first grave ever dug in Jacksonville was for a white man that was shot down by a gambler, and the next grave was for his murderer, who was convicted by a miner's jury, before W. W. Fowler, "alcalde," and hung on a warrant of the "alcalde." White men and Indians were all liable to the same punishment. It was by high miner's court from which no appeal would lie; it was quick and beneficial. "Pioneer Times," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, August 21, 1886, page 2 I slept well that night and next morning started on my road to Jacksonville. When I got near the summit of Siskiyou Mountain I had a splendid view of the Mount Shasta. I met a party coming from Jacksonville. . . . [One of them] told me of a murder at Jacksonville and of the hanging of the murderer by the vigilantes. I knew the man that was hanged; he had a claim next to mine on Humbug, above Minersville; his name was John Brown from Pike County, Illinois. He had come out in 1849 or 1850, and his father and brother had gone home, back to Illinois, from the southern mines, and he . . . came north and worked on Humbug Creek in 1851 and 1852. . . . Brown was a gambler, and I heard that he used to go with the Indians a great deal before he went to Jacksonville. He was a good foot racer and rassler, very stout build, about 24 or 25 years old. Dejarlais saw Brown hanged and he says if he had a cool, fair and impartial trial he might have been cleared, but he was tried by excited miners who worked up a prejudice against the gambler, and Brown was called of that class, then very obnoxious to the miners, who had lost money with them, and were mad at them for beating them out of their money. But if they had won it would be all right. But Brown was in a manner justified, for he had great provocation. I will here state the case as I heard it afterward in Jacksonville. John Brown was considered a gambler and he ran with gamblers, but he was sick and could not work. The man he killed was a large, robust man, over six feet tall and weight over 200 lbs., [who] was drinking and blustering about in Jacksonville that he could out-run, throw down, or whip or out-jump anyone in town. Some men in fun called to Brown to come and run a foot-race against the big Missourian. (Brown was quite fast on foot.) But Brown said he was not well enough to run. But the big Missourian thought that Brown was afraid of him, and he could bluff him because he was sick. So he commenced to dare him to run, and as Brown would not, and turned away from him, he said Brown was nothing but a horse-thieving son of a b---- and he could whip him or outrun or throw him down, and abused Brown to what he could lay his tongue to. Brown left the crowd and went and got a navy revolver and put it in the bosom of his shirt and down under his belt, and he came back where the big Missourian was still blustering around cursing and swearing at everybody. Brown walked up to him and asked him to repeat his words that he called Brown. The big Missourian came toward Brown and as he came he unbuckled his belt containing his pistol and knife and handed the belt to some friend of his, expecting that Brown had come back to fight him. He came to Brown and said, "You are a lying, gambling, horse-thieving son of a b----," and doubled up his fist to strike Brown when Brown had his hand in his bosom on his pistol, and drew his pistol and shot him through the heart, and he fell back and soon died. Brown gave himself right up to the city marshal and it caused great excitement. The miners were for lynching Brown right off; others formed a vigilance committee to try him next day. Some thought Brown had done right; some thought not. And what made it worse was that the wife and three children of the Missourian had come out and got there a short time after he was shot, and the miners all sympathized with the widow and her three children, and that her husband had been cruelly murdered by a gambler was adding to the crime against Brown. But he, Brown, still claimed he had done right, that if he had been well he would have fought him, but being weak and sick, he could not look over the names that the Missourian had called him and his mother, and if he had it to do again he would do the same every time. . . . But the friends of the killed man said he was drunk and should have been excusable for what he said. So the next day the miners all met; they had a vigilance committee and a judge and jury elected by the miners to try Brown, and after a little while the jury found Brown guilty of murder and he was to be hung next day close to town. A guard of fifty men (vigilantes) guarded the jail, and next day he, Brown, was hauled in a wagon to the place of execution. His hands and feet were bound and several hundred horsemen armed with rifles and shotguns ranged along the wagon until they got to the gallows, hastily constructed, not far from Jacksonville. They were careful not to take his fetters off his feet and hands until they got on the gallows, for it was Brown's only hope that they would untie his feet and hands and he would have made a rush for the hills, and in the confusion he might have got away, for no doubt he could have outrun any man afoot on the ground, and they knew it, and kept him tied until they put the rope around his neck. They asked him if he had anything to say; he said only a few words--that he thought he had done right, and if it was to be done over would do the same; bid all friends goodbye and died game. The authorities at Jacksonville apprehended a rescue by the California friends of Brown, but they did not get the news until he was about hung, and it was too far to go to avenge the death by what few friends he had around Yreka or Humbug Creek. Doyce B. Nunis, ed., The Golden Frontier: The Recollections of Herman Francis Reinhart 1851-1869, written 1887, published 1962, page 36 In May 1852 . . . a miner named Plott was shot and instantly killed by one Brown. The miners and others collected immediately, and surrounded the murderer. Elected a judge and jury of 12, tried and convicted and hung him, erecting a scaffold for the purpose. As there was no jail or handcuffs, the prisoner had to be guarded all the week and Mr. McDonough was one of the guards. Mrs. R. M. McDonough and Elizabeth T'Vault Kenney, letter of November 26, 1899 "As in all mining towns of California, before county organizations were perfected, an alcalde was elected in each Southern Oregon town to administer justice in all cases. The same was done in Jacksonville. This officer's authority extended over everything, from a petty offense to a trial for life. The day I arrived in Jacksonville, a murder was committed. The murderer was immediately arrested, and the next day a jury was empaneled, a prosecuting attorney and counsel for the defense were appointed, the defendant was duly convicted, and he was sentenced to be executed in 10 days, which sentence was duly carried out. During about one year and a half this was the only court held in what now constitutes the counties of Jackson, Josephine, Lake and Klamath. For about one-half this time I was the alcalde, and had quite a number of interesting cases before me. . . . These alcaldes had but about a dozen laws or articles for their guidance, and no technicalities were allowed. A trial consisted of the statements of the parties and the evidence of witnesses, if any, and the case was decided by the court, or the jury, if either party wished one. There was but little dissatisfaction with the decisions of the court. In fact the whole community was ready to help enforce the decision if it was necessary." Chauncey Nye, "Early Legislature," Crook County Journal, January 2, 1902, page 1. An edited version was printed in the Medford Mail, January 24, 1902, page 3 FIRST HANGING IN SOUTHERN OREGON

In order

to get an intelligent

understanding of the situation and the chaotic condition of society

prior to and at the time of the execution, it must be explained that

the mines on Rich Gulch within the limits of Jacksonville were

discovered by a party en route from the Willamette Valley to

Yreka

late in the fall of 1851. After crossing the Rogue River the party kept

near the foothills to avoid the dangerous Indians on Bear Creek, and

camped overnight on the present site of Jacksonville. While some of the

members were preparing supper, James Pool took a pick and pan and went

down to the bed of the gulch to prospect, and was happily surprised to

find that every pan yielded the most flattering results. The party made

a permanent camp, staked off claims and went to mining. The gulch

proved to be very rich. Yreka was at that time a booming mining camp.

The flats and gulches in and around the town literally swarmed with

men, and the new discoveries from day to day kept the transient

population at fever heat. When the news of the discovery of Rich Gulch

reached there, exaggerated as discoveries always were in those days, an

avalanche of men swept over the Siskiyous, and by the spring of '52,

3000 or 4000 miners were delving in the hills and streams around

Jacksonville.Miners Organize a Court Which Tried and Convicted a Murderer in 1852 ----

It must be

remembered that at this

time there were no county organizations, no courts, no executive,

judicial or peace officers, and that every man was a law unto himself.

And when it is considered that this large influx of excited miners

represented every nationality, that every type, color and condition

could be found among the throng, that they had been trained and

educated under dissimilar influences, entertained different beliefs on

political, social, religious and governmental questions, that they were

as widely divergent in tastes, inclinations and purposes as the

countries from which they came were distant from each other, that there

was no common bond of union, fraternity or national brotherhood between

them, and no restraints of society--when the anomalous situation is

fully understood it is little wonder if crime should have run riot and

murder and robbery stalked unpunished through the camps. But though the

situation would seem to invite and specially favor reckless and

unrestrained lawlessness, yet little comparatively prevailed. A due

sense of such prudence and civility as would best inure to personal

safety, combined with a wholesome fear of the swift and stem justice of

miners, constrained each and all to an observance of those principles

of peace and amity which characterize all civilized peoples. And so

there was little crime except of a rollicking, social and reckless

nature which might be reasonably expected in a large, unorganized

community of transient strangers. Such a notable absence of crime under

such conditions may be regarded as truly remarkable.----

In April,

1852, a man who was

called Brown by his comrades, but whose right name was Jackson Maynard,

a gambler, killed Samuel Potts, a rancher, in front of the "Round Tent"

a large canvas enclosure built and used for gambling purposes. Potts

had taken up the well-known Eagle Mills place, two miles below Ashland,

and built a house over the hot spring that issues from the bluff on the

south side of the road, and running short on provisions, went to

Jacksonville to buy supplies. There was a foot race in town during the

afternoon, and the gamblers appear to have been thrown down, at least

they thought so, and the race created a great deal of adverse comment

among the sporting fraternity. Maynard and Potts had both been drinking

and were ugly and quarrelsome, though they were not considered to be

drunk. They met at the door of the Round Tent where the race was being

discussed, and a quarrel ensued between them, during which Maynard drew

his pistol and killed Potts. As far as [is] known Potts made no attempt

to assault Maynard, but was shot without provocation other than words

in which Maynard was quite as offensive as Potts. Jackson Hot Springs, March 5, 1916 Oregonian ----

A great

crowd assembled

immediately after the shooting, and the uniform sentiment was that as a

matter of self-protection, and as an example to desperadoes and vicious

persons, Brown should be arrested and tried, and if found guilty

punished in accordance with the judgment of the court before whom he

was tried. A. meeting was called, and W. W. Fowler selected as judge

and Abe Thompson as sheriff. Thompson at once arrested Brown, and

guarded him securely until next day, when 12 disinterested persons,

found to be such after careful elimination, were selected as jurors to

hear and decide the case. Columbus Simms, afterwards if not at

that time Territorial Prosecuting Attorney, appeared for the territory,

and David Branen and another attorney whose name I cannot at this time

recall appeared for the accused. The trial was commenced and conducted

to its close strictly in accordance with the forms of territorial law,

and with all the dignity and decorum observed in regularly constituted

courts. The same order was maintained, witnesses were examined and

cross-examined with the same painstaking care as in authorized courts,

the usual objections were made to irrelevant or illegal questions, and

the issues carefully considered and passed upon by the judge; and upon

conclusion of the testimony, the argument of counsel, and charge of the

judge, the jury was locked up in charge of a sworn guard to deliberate

upon its verdict. After being out about two hours the jury reported to

the guard an agreement, and on returning into court, the foreman handed

in a verdict of murder in the first degree. The evidence was so

positive and conclusive against the accused that the judge thereupon

sentenced the prisoner to be hanged at a certain hour eight days

thereafter, and charged the sheriff to guard and safely keep the

prisoner till the day and hour named. When the time of execution

arrived, the prisoner was brought out under an armed guard of 12 and

marched to the gallows which had been previously erected, and having

been placed on the platform, the death warrant was read to him, his

hands and feet pinioned, and the black cap being drawn over his face,

the rope was cut and the condemned man shot down like an arrow, and

hung suspended with his neck broken in full view of the great throng

that had assembled to witness the hanging.----

This was

the first execution in

Southern Oregon, and though there were no legally authorized courts,

and no executive or peace officers, the whole procedure from the arrest

to the execution was carried out strictly in accordance with the

criminal practice of the territory save in the matter of indictment and

perhaps also as to the early execution after the sentence. Respecting,

however, the short time allowed the condemned man after the sentence,

it will be remembered that when the Indians Tom and Thompson were tried

before United States Judge O. B. McFadden, at Jacksonville, February 7,

1854, for the murder of citizens, they were convicted and the judge

only gave them three days' grace, from February 7 to February 10, when

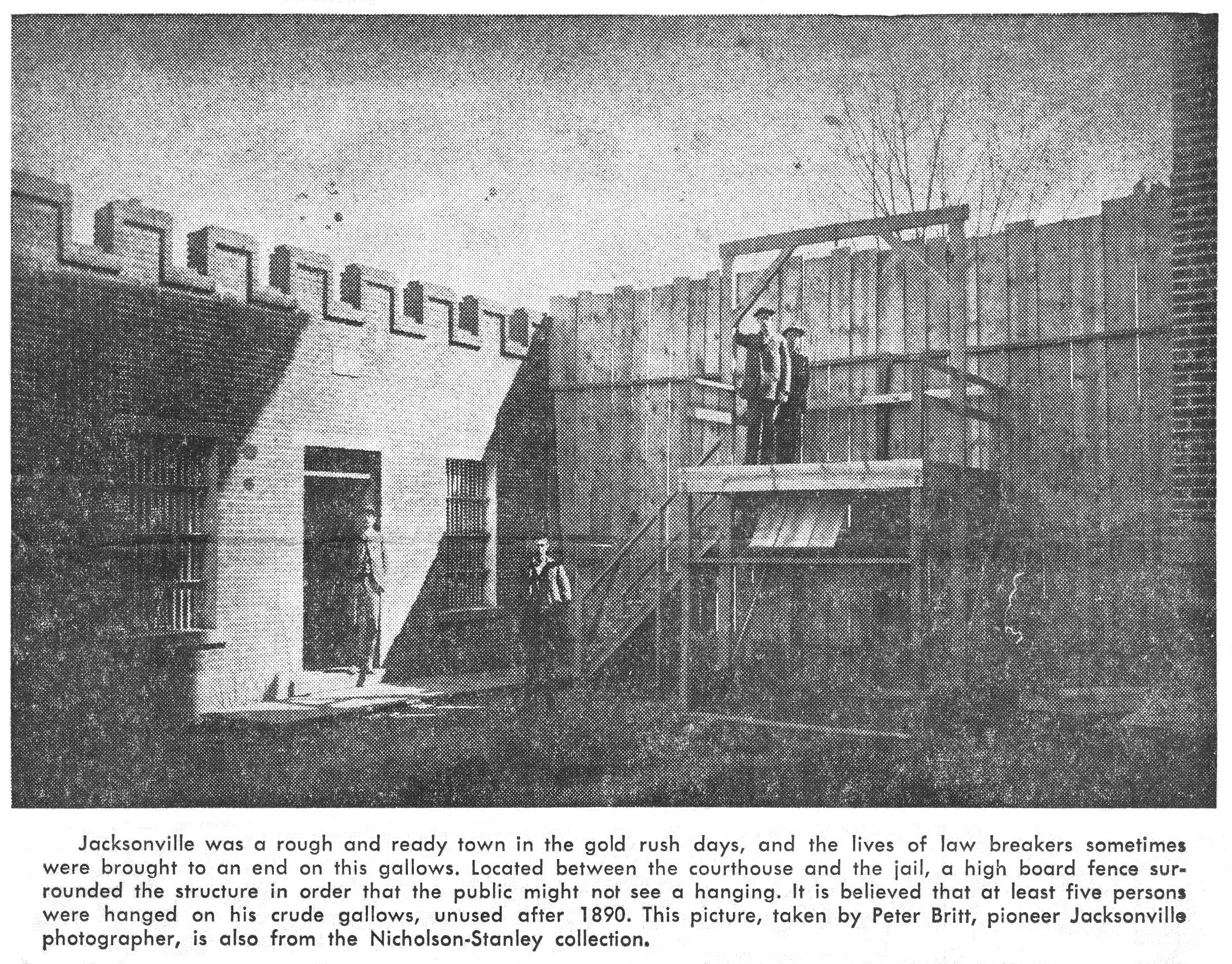

they were hanged.Brown's gallows was constructed by planting four posts in the ground, two long and two short. The platform was swung between them on two ropes, so adjusted as to make the platform secure. The ropes were then brought together at a convenient place where, with a single blow of a hatchet, the platform could be instantly freed. The gallows was erected on the flat in front of the present public school building, and the posts stood there for many years as grim reminders of the penalty meted out by miners to evil-doers. Brown's [Maynard's?] body was buried on the banks of Daisy Creek, a small stream that issues from Rich Gulch, on a lot afterwards owned and occupied by Hon. C. C. Beekman as residence property, Brown's [Potts'?] remains having been taken up and buried in the old Jacksonville cemetery. This recital will be news to nine-tenths of the people of Jacksonville, who never heard of Brown or the execution. It would be interesting to show the alarming increase of crime after the organization of the county, March 7, 1853, but it would make this article too long. While the evil-disposed did not fear the regularly constituted authorities, they had a wholesome dread of the swift and unerring justice of the miners. W.

J. PLYMALE.

Roseburg, June 17.Sunday Oregonian, Portland, June 21, 1903, page 15 First Murder and First Hanging in

Rogue River Valley.

The

first murder committed in Rogue River Valley by a white man killing a

white man took place at Jacksonville in March 1852, when a man known as

Brown killed a man by the name of Potts. The incidents connected with

this murder are given to the Rogue

River Fruit Grower by

E. K. Anderson, one of the earliest settlers in Rogue River Valley, and

who formerly lived on Anderson Creek, near Talent, but who now resides

in Ashland. Mr. Anderson saw the shooting, and he acted as one of the

jurymen at the trial of the murderer, and he was one of the guards at

the execution of the condemned man. White men had been killed by

Indians before this time, but there is every reason to believe that

this was the first instance of a white man killing a white man in this

valley.

Jacksonville at that time was a mining camp that had been established only about two months, for it was only the previous December that gold had been discovered in Rich Gulch [by] James Pool, who with James Clugage had come that month from Yreka to winter their train of pack horses and mules on the luxuriant grass that then grew all over Rogue River Valley. It was not until January that news of the finding of this new and fabulous rich diggings reached the California old miners, and then there was a rush across the Siskiyou Mountains to the new camp, which had been named in honor of President Jackson, who was then the popular idol of Americans and especially of the Southerners, many of whom were in the rush to Rich Gulch. At that time Jacksonville was a town of tents, though Mr. Anderson thinks there may have been a few cabins built of poles, but if there were he has forgotten them in the 58 years since that eventful spring. The only woodworking tool then possessed by the miners, and by the not over a dozen farmers who within the month had settled in the valley, were axes. With these the miners and ranchers cut the logs for their cabins and in some instances, before froes were brought in, split clapboards with which to roof the cabins. So far as Mr. Anderson recollects, and his memory is very clear and accurate, Jacksonville, at the time of the killing of Potts, had a population of about 400 men, but there were no women, for it was a month later when the first woman came to the valley. Most of these men were miners, and there was also the large number of gamblers, saloon keepers and camp followers. It was shown at the trial that the murderer Brown was a worthless young man who loafed about the saloons and gambling places. Just before he was hung he stated that his true name was Maynard, but he would not tell anything as to his past history or of his relatives. Potts was a young man who had come to the valley about a month previous to his death and had taken up a land claim on Bear Creek two miles below the present town of Ashland, the land now belonging to D. H. Jackson. On this place are big warm springs, and it was Potts' plan to conduct on his place, in addition to farming, a health resort for the treatment of rheumatism, a trouble that afflicted many of the miners. He was a quiet, industrious young man, but nothing was known of Mr. Anderson as to his previous history. The day that Potts was killed Mr. Anderson was in Jacksonville for supplies, he then living on the claim that he had taken up three months previously on the stream since named Anderson Creek, he being the first settler in that part of Rogue River Valley. At that time the saloon, gambling, trading and boarding house tents were ranged in fairly regular order along about where now stand the business houses in Jacksonville. Mr. Anderson was standing on the corner where is now the Masonic block, when he saw a man dash out of a saloon tent, and close after him was another man brandishing a pistol. As they reached the middle of the street the rear man shot the man he was pursuing in the back, killing him instantly. It was all done so quickly that the bystanders had no time to prevent the shooting, but smoke from the murderer's pistol had not cleared away when he was covered by half a dozen revolvers and forced to surrender. There was no law nor no courts at that time in Rogue River Valley, and the murderer had hardly been disarmed when the [men who] quickly gathered made a move to lynch him. This was prevented by Mr. Anderson and other cool-headed men, and it was decided to give Brown a fair trial. A meeting was called and a judge and prosecuting attorney were chosen, and there was also a man selected to act as attorney for the accused. A sheriff and a guard were appointed to take charge of the prisoner. A clerk of the court was also appointed, and this official, from a list of names that had been prepared, drew by lot the names of the six men who were to act as jurymen. Mr. Anderson was one of the men so selected. After the trail had been held he was also made a deputy to the sheriff and assisted in guarding the prisoner and at the execution. Miner's justice is always swift and sure, and in this case all arrangements for the trial of the murderer were completed by the day following the shooting. In this improvised court the formalities and technicalities of modern courts, that delay procedure and often enable the guilty to escape conviction or at least to avoid punishment for an indefinite time, were not practiced, nor would they have been allowed if attempted. The court held its session in one of the big tents, and the trial lasted but half a day. After the evidence had all been heard the two attorneys made their pleas. Both addresses were short and to the point, that of the prosecuting attorney emphasizing the proof that a willful murder had been committed and that the murderer should be convicted and hung as a punishment that he deserved and also that the execution would be a warning to others criminally inclined. The attorney for the defense conceded that his client had killed the man, but that the homicide had been committed as the result of a drunken row and that the pistol shot had been fired while the accused man's brain was crazed by whiskey, and under these circumstances he asked the court's leniency. The jury quickly came to a decision, and on their verdict the judge sentenced the prisoner to be hung on the following Saturday morning. It was on Tuesday of that week that the murder was committed, and the trial was held Wednesday, but Mr. Anderson is not certain as to these dates, and the events may have been a day later in the week. But he is sure that there was an interval of time allowed the doomed man to arrange his affairs. The execution took place north of where the courthouse now stands in Jacksonville. Though the entire population of Jacksonville and vicinity were present, there was no disturbance, and the execution was as orderly as those of today that are carried out by regular process of law. Only a few days previous the first wagon had reached Jacksonville, and one of these was made to do duty as a scaffold. [Wagons were passing through the Rogue Valley, with difficulty, as early as 1846.] The condemned man was made to stand on the wagon, and then a rope was placed about his neck and made fast to a limb of an oak tree. The wagon was then drawn away, and the man was left swinging in the air and soon died. From the time of his arrest until his execution Brown maintained a stolid indifference and would make no statement concerning his past life, nor would he give any directions for notifying his relatives or friends in the East of the tragedy that led to his death. Only at the last moment, after his hands and feet had been tied and he was given a last chance to speak, did he tell anything of himself, and then he only stated that his right name was Maynard and that Brown was only his assumed name. Mr. Anderson took no part in the burial of Potts nor of Brown, and he does not recollect as to where the two men were buried. So far as he can recollect of the early history of Jacksonville Mr. Anderson is of the opinion that the grave dug for Potts was the first one, and that of Brown the second one for burial of a white person in Oregon's first mining town. Rogue River Fruit Grower, October 1910 Anderson remembered Potts' name as "Plot"; I've changed it for consistency with other memoirs. One man named Brown shot a man named Potts in the summer of 1852. The guilty one was tried by a jury of which David Linn, father of Fletcher Linn, of Portland, was a member. The slayer was hanged at the present site of an old Presbyterian church. "Jacksonville Is Real Relic of the Hardy Pioneer Days," Oregonian, Portland, November 6, 1910, page 4 Justice was administered [in early Jacksonville] by the people's court; its findings were singularly correct, its decrees inflexible, its punishment certain. In 1852 the first court of this character was convened; a miner named Potts was shot dead without provocation by a gambler named Brown. Immediately every claim was vacated. Men not angry but outraged by the deed gathered in hundreds, and the assassin was secured. That fine sense of chivalry and fairness common on the frontier prompted a proper investigation, and in the absence of even a justice of the peace, W. W. Fowler was appointed judge and a jury of twelve men was selected. The case was tried by the rules of right and wrong divested of legal technicalities. Brown was readily proved guilty of a cowardly murder and taken to an oak grove a little north of the site of the Presbyterian Church, hanged and buried under a tree a few yards west of where the church now stands and the remains have never been removed. The court was quietly dissolved, the judge disclaiming the right to exercise further jurisdiction, but the lesson was salutary and effective. "True Tales of Pioneers," Jacksonville Post, August 21, 1920, page 1 ----

"Warty," August 1852: AN INDIAN HUNG BY THE WHITES.--We learn from Mr. Stewart, of Dugan and Co.'s Express, that an Indian called Warty was hung by the whites at Rogue River a few days ago. This Indian is said to have committed many robberies and other crimes upon the whites and to have been the most reckless one among them. In this case he entered the house of a Mr. Weaver and demanded bread, which was refused him by Mrs. Weaver, who was alone with her children. The Indian proceeded to help himself, and upon being opposed by Mrs. W. drew his knife upon her; an alarm was given by the children, when some men who were at work nearby, hearing the alarm, and knowing the Indian character, arrested him, summoned the neighborhood, tried, condemned, and hung him the same day. Oregonian, Portland, August 14, 1852, page 2 ----

Old Taylor and another Indian, June 1853: An Indian called Old Taylor, brother to Joe and Sam of Rogue River Valley, was hung lately for assisting in the murder of several white men. "Siskiyou," Sacramento Daily Union, June 27, 1853, page 3 Old Taylor, the chief, and two others, were hung a few days since. Yesterday another marched up to the rope. There is a party of whites forty strong, under Capt. Bates, in hot pursuit of the villains. The Grave Creek Indians must die. Taylor and party killed seven whites last winter, and then reported them drowned in Rogue River during the storm, for which a portion of this tribe have paid the popular penalty. "Indian Difficulties in Rogue River," Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, June 28, 1853, page 2 ----

The two Shastas and the Indian boys, August 6, 1853: Jacksonville, Oregon

Aug. 7 / 53

I write this in great haste; everything

and

everybody is in great excitement about Indian war. The Indians of this

valley have turned against the whites. They have killed two men and

wounded some five or six since last Friday evening. The whites turned

out yesterday and killed some six or seven Indians besides hanging

three here in town.John R. Rice, SOHS M42A Box 2, #82-147 On Saturday, Mr. Rhodes Noland was shot dead in his cabin door within a mile of town. The citizens who had been previously preparing for a skirmish, upon receiving intelligence of his murder, immediately started out and in a short time returned with a captive "siwash tyee" ["Indian chief"], who was mustered to an oak tree and there "strung up." During the day three others were hung beside the tyee. T. McF. Patton, letter of August 6, 1853, Oregon Statesman, Salem, August 30, 1853, page 2 The Rogue River War was commenced by Shasta Indians who had been driven from Shasta Valley. They killed a man named James Kyle, within hearing of the center of the town on the road coming from Yreka Sat. night Aug. 2nd, '53. [This was apparently Thomas Wells/Wills; Kyle was killed on Oct. 7; see below.] This fired the citizens & miners acting made indiscriminate war on the Rogue River Indians. A meeting of the citizens were called that night. They slaughtered indiscriminating war on Rogue River or Shasta Indians, though of the latter there were but few, and so those most guilty suffered the least. Two Indians were captured on Applegate, which is a tributary of Rogue River, lying 8 miles south of Jacksonville. These Indians had on the war paint; they were brought to Jacksonville and in a few hours hung by the citizens and probably justly. But the saddest part of the tale remains to be told. About four o'clock in the evening, two farmers from Butte Creek brought in town a little Indian boy 8 or 9 years old. The cry was Hang him! exterminate the Indian! The miners put a rope around his neck & led him towards the tree where the others were hung. B. F. Dowell mounted a log in the vicinity, made a brief speech to the excited crowd of 1000 men, in behalf of the Indian & humanity. Someone cried out what will you do with him? I replied "Take him to the tavern and feed him at my expense." The excitement subsided & they gave me the Indian. Mr. Dowell removed the rope from his neck & led him toward the tavern. At this moment Martin Angel, an old citizen & brave soldier, rode up in an excited manner, cried out, "hang him! hang him! we've been killing Indians all day!" The excited mob rushed and took the Indian from Mr. Dowell, and in a moment had the boy hanging from the same tree from which the two men were suspended. Mr. Dowell resisted after the rope was placed the second time and cut the rope, but the crowd seized him and held him until the execution occurred. Less than a year and a half after in Jany. '56 Martin Angel paid the forfeit of his crime by being assassinated by the Indians on the road above Jacksonville leading to Crescent City. This boy had been employed with the farmers on Butte Creek--farming. During the Rogue River War Mr. Dowell carried the mail between Cañonville and Yreka as mail contractor, and never was molested by the Indians. After the war, Chief Limpy told him that he could have killed him several times, but that he wouldn't hurt a paper man and one who had tried to save a "tenas tillicum," little papoose. Interview with Benjamin Franklin Dowell, Bancroft Library MSS P-A 25-26 On the 7th of August, the miners captured two Shasta Indians, one on Jackson Creek, and the other on Applegate. These Indians were both in their war paint when caught. They were brought to Jacksonville and on examination it was found that the bullets belonging to one of their guns were the same size of the one with which Noland was killed. There were other facts and circumstances which tendered to identify them as the guilty parties. They were tried by a miners jury and hanged before 2 o'clock the same day. In my opinion they were justly punished. (In justice to the military authority at Fort Lane, we will add that they assisted in bringing these Indians to justice, and endorsed the action of the citizens in the matter.--Ed. Tidings) One of the saddest and most inhuman acts of the whole war remains to be told. Late in the evening of the day those Indians were executed, a small innocent boy about nine years old was brought to Jacksonville by three men from Butte Creek, with whom the boy had been living. The poor little boy on being discovered by the miners [was] taken to a place near where David Linn's cabinet shop is now standing, and near where the scaffold where the two Indians were still hanging. I mounted a log near by, and called the attention of the vast crowd to the solemnity of the act they were about to perpetrate. I called on them to punish the guilty, but to spare the life of the innocent child. While pleading at the top of my voice the crowd gathered around the hangman's tree. Someone called out "what will you do with the boy." I replied, I will take him to a hotel and feed him. I went to him and took him by the hand and started up California Street when Martin Angel came up on horseback and without alighting commenced to harangue the mob against the murderous Indians. He said: "The war was raging all over Rogue River Valley, we have been fighting Indians all day; hang him, hang him; he will make a murderer when he is grown , and would hang you if he had a chance." The mob at once seized the boy and threw a rope around his neck, which I succeeded in cutting twice. I was violently thrown back by an Irishman, of the firm of Miller, Rogers & Co., of the left-hand fork of Jackson Creek. The excitement was so great that I found that my own life was in danger, and I had to withdraw. In a moment more the boy was swinging to a limb. I turned away with a sad heart at this inhuman conduct towards the innocent child, against whom no crime was charged. No mob ever committed a more heartless murder than this. "The Beginning of the Rogue River War--The Murder of the Indian Boy, etc. etc.," Ashland Tidings, October 25, 1878 Other incidents of the eventful period preceding Lane's campaign of August 21-25, were the capture and shooting of a suspected Indian by Angus Brown, the hanging of an Indian child in the town of Jacksonville, and other acts of that nature, which reflect no credit upon those engaged therein. That stern-visaged war had wrought up people to deeds of this sort, is not very remarkable. Five Indians, it is credibly reported, were hanged in one day, on a tree which stood near David Linn's residence. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 217 1853 was a year of troubles and excitement in the new town. A deadly war had been determined on by the Indians who were every day more emboldened by success; more eager for blood as each successive white life was taken. Several settlers in the outskirts of the valley had been picked off by straggling Indians. One afternoon in August the crack of a "Siwash" rifle was heard just in the eastern edge of town; a riderless mule with a bloody saddle galloped madly along California Street, and was recognized as that of a prominent citizen, Thomas Wills, who had been absent from town but for a few hours. Armed men went instantly to where the shot had been heard, and soon returned with the bleeding body of Mr. Wills, who had received a mortal wound and survived only a few days. This audacious act angered and alarmed the townspeople, and among the families there was intense excitement, there being scarcely a bulletproof habitation in town, which could be easily approached under cover from nearly every direction. To make matters worse, arms were by no means plenty, and there is little doubt that had an attack been made in force, and the savages been willing to risk their skins, they might have captured and destroyed the little town. The people, aroused to a sense of danger, effected a partial organization for defense. Pickets were thrown out nightly, and the greatest vigilance was exercised by day, but notwithstanding all precautions only a few days elapsed until a man named Nolan was shot dead within rifle range of the business street. This species of warfare was exasperating, and it was but a few days before the Indian method of reprisal was resorted to. Two Indian boys, "Little Jim" and another, mere striplings, came into town, perhaps from motives of curiosity, possibly as spies. It was scarcely probable that they were the miscreants who lay in wait at the very threshold of the town to slay unoffending whites; there was not the slightest evidence that they had committed any crime--they were too young to be warriors--but in the bitter anger of the moment it was sufficient that they were Indians. They were soon seized by an excited crowd who scarcely knew what to do with the terror-stricken prisoners, and some of the roughest shrank from the commission of an act that they knew was not brave, and that they feared was hardly just. The mob swayed and surged, wavering between desire and doubt, when T. McF. Patton sprang upon a wagon and in a few words decided the question. The boys were hanged on an oak on the bank of Jackson Creek, while protesting piteously that they had never wronged the whites. Sober reflection brought regret for an act that by no means exalted the white character, and it is very probable that the dreadful savagery subsequently experienced by white families was in retaliation for a deed that, in calmer moments, was regretted as neither courageous nor justifiable. This was the last session of the people's court in Jackson County, for on September 5, 1853, a regular court was held in Jacksonville, by Hon. Matthew P. Deady, who had just been appointed United States district judge for the Territory of Oregon, by President Pierce. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 362 In August, 1853, [B. F. Dowell] mounted a stump and made a speech to a mob that had a rope around an innocent Indian boy's neck until they wavered so he was permitted to take the rope off the boy's neck, and he took the little fellow by the hand and started for Robinson's Hotel to feed him, and on the way they met a still more infuriated mob, who took the boy back and hung him with the murderers of [Rhodes] Noland. Benjamin Franklin Dowell, The Heirs of George W. Harris and Mary A. Harris, Indian Depredation Claimants vs. the Rogue River Indians, Cow Creek Indians, and the United States, 1888, page 58 At the close of hostilities [in 1853, Major James Bruce] discovered the peril of entering with but one companion into an armed and excited Indian camp. He performed this intrepid feat at the request of General Lane, who had given the Indians a three days' armistice to come in and conclude a peace, but was annoyed and even perplexed by their failure to do so, and indeed by their entire disappearance. Bruce and R. B. Metcalfe were directed to scout the mountains for the camp of Chief Joseph. After three days' investigation they found him with all his tribe encamped as if for war in a natural fortress. To enter this stronghold and deliver their errand to bring in the Indians was a matter of great delicacy. But descrying the tent of Chief Joseph, which was distinguished by a blue cloth, the spies determined to go to his lodge, relying for safety upon his well-known desire for peace. Before attracting his attention, however, they were seen by the young braves, who assembled in great numbers, running and hooting, and manifestly bent upon spilling the blood of the intruders. Bruce and Metcalfe saw in a moment that their death was imminent; and the Major believes that they must have been slaughtered had not an Indian boy named Sambo suddenly appeared, shouting and averring at the top of his voice that this white man was not to be killed--that he had saved his life and must now be saved. Major Bruce was only too glad to recognize in this youth his Sambo, the Indian formerly the rider of the bell horse on his pack train, whom he had actually saved sometime before at Jacksonville from the hands of the infuriated miners, who were indiscriminately hanging the Indian bell boys then in town. By the shouts and exertions of this faithful Sambo, a diversion was created; and Joseph appeared, by whom the scouts were severely censured for their temerity. Nevertheless they gained time and explained their mission, and at length accomplished their purpose, bringing the chief to General Lane. The Major, however, always thinks with tenderness of the boy Sambo, whose fidelity saved him from a dreadful death. Elwood Evans, History of the Pacific Northwest Oregon and Washington, vol. II, Portland 1889, page 228 . . . on the fifth [of August, 1853], Thomas J. Wills and Rhodes Noland were killed, and Burrel B. Griffin and one Davis wounded. Hastily formed volunteer companies patrolled the roads and warned settlers, who gathered their families into a few fortified houses, and setting over them a guard, joined the volunteers. On the seventh of August two Shasta Indians were captured, one on Applegate Creek and the other on Jackson Creek. Both were in war paint, and on investigation were proved guilty of the murder of Wills and Noland, for which they were hung at Jacksonville. Not satisfied with this act of justice, an Indian lad who had nothing whatever to do with the murders was seized and hung by the infuriated miners. So great was the excitement that it was dangerous for a man to suggest mercy. Frances Fuller Victor, Early Indian Wars of Oregon, 1894, page 308 Two Indian boys came to town [one] named Little Jim and another mere stripling whom the people thought were spies. They were seized by an excited crowd that did not know what to do with the prisoners. The mob wavered between desire and doubt until F. M. Patton decided the question. The boys were hanged on an oak tree near Jackson Creek protesting all the while they had never wronged the whites. Jessie Beulah Wilson (Jacksonville High School student), "History of Jacksonville," Jacksonville Sentinel, June 5, 1903, page 4 ----

Indian Tom, Indian George and Indian Thompson, January 10, 1854: It's possible that Indian Tom and Indian Thompson were the same person. Fort

Lane O.T.

Sir,Oct. 12, 1853 On the night of the 7th two Inds. shot a man by the name of Kyle, who was a partner of Wills, one of the persons shot at the commencement of the late war. It occurred near Willow Springs at about 10 o'clock at night. The two Inds. belong on the Klamath, though they have spent much of the last year with those in this valley. One of them is related by marriage to Tyee Jo & they both have many friends among the young Indians here. And it was a severe test of the Inds.' desire for peace to be compelled [to] deliver them up. But they did so yesterday morning. They are now in the guard house, where they will be kept until the next term of the dist. court. I think peace now more firmly settled than ever. Very

respectfully,

Joel Palmer Supt. &c.Your obt. servt. S. H. Culver Ind. Agt. Milwaukie O.T. Oct. 13. P.S. Kyle died this morning. Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Reel 12; Letters Received, 1853, No. 66. INDIAN FAITH.--Mr. James Kyle, an estimable citizen of Jackson County, and partner of Thomas Wills, who was killed in the war, was recently murdered by some Indians near Willow Springs. Col. Wright immediately demand the murderers of the chief Joe, and they were promptly brought in and delivered up, even before Mr. Kyle died, he not having been instantly killed. The Indians will be tried and punished. This act shows a disposition on the part of Joe, who is the head chief, to observe the requirements of the treaty. A more particular account of this affair will be found in our Fort Lane letter. Oregon Statesman, Salem, November 8, 1853, page 2 Indian

Agency

Sir,Southern District O.T. Febry. 14, 1854 The two Indians that I have in custody charged with having been the murderers of James Kyle, also one that was delivered to me as the murderer of Mr. Edwards, were executed on the 10th instant. One that I had in custody charged with theft was acquitted. I find it necessary to be constantly among the Indians. They take the loss of these three Indians much to heart (their relations) and must be watched closely. I returned late last night from Applegate Creek & am trying to get all of these relatives in to the agency. The mail will leave in a short time. I have only time to express the hope that nothing will prevent a farm's being started on the reserve for the benefit of the Indians next spring. Respectfully

yours

Joel Palmer Supt. &c.S. H. Culver Ind. Agent Microcopy of Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs 1848-1873, Roll 4; Letter Books C:10. The murderers of Edwards and Kyle were tried in the district court at Jacksonville on the 7th and 8th of January, 1854. They were found guilty and hanged on the following Friday, being the 10th day of January. The following particulars of the trial of those murderers are gleaned from the records of the court. The officers of the court were Hon. O. B. McFadden, Judge; C. Sims, Prosecuting Attorney; Matthew G. Kennedy, Sheriff; and Lycurgus Jackson, Clerk. The grand jury presented indictments against Indian Tom and George for the murder of James C. Kyle. They were brought into court and arraigned, and having no counsel, the court appointed D. B. Brenan and P. P. Prim to defend them; these attorneys being their choice. Louis Dennis was appointed, in connection with Mr. Culver, to act as interpreters to the court and jury. Indian George was first put on trial, and the following jury was empaneled to try the case: S. D. Vandyke, Edward McCartie, T. Gregard, A. Davis, Robt. Hargadine, A. D. Lake, James Hamlin, Sam'l. Hall, Frederick Alberding, F. Heber and R. Henderson. After hearing the evidence in the case, arguments of counsels and charge of the judge, they rendered a verdict of murder in the first degree. On motion of the prosecuting attorney the court proceeded to pronounce the following sentence as the judgment of the court. You, Indian George, have been indicted and tried for one of the highest offenses known to the law, to wit: The crime of murder. You have had a fair and impartial trial, as much so as if you had belonged to our own race; you have had the benefit of counsel who did everything for you that was possible. But an intellectual and upright jury, upon a fair and dispassionate examination of the evidence given against you, not only by those whom you suppose to be unfriendly toward your people, but by the chiefs of your own tribe, have found you, Indian George, guilty in manner and form as you stand indicted, of having on the night of the 7th of Oct., 1853, deliberately, and without premeditation and malice, shot Jas. C. Kyle, and as there was no provocation on the part of Mr. Kyle which could justify you in the use of violence toward him, they have said that you are guilty of murder in first degree, an offense which by our laws is punishable by death. It, therefore, becomes my duty to pass on you the sentence approved by our laws. The sentence of the court is, that you, Indian George, be taken hence by the Sheriff of the county of Jackson, and be by him, the said Sheriff, kept and detained in safe and secure custody until Friday, the 19th day of February, A. D., 1854, and between the hours of 10 o'clock a.m., and 12 a.m., of said day; and that you, Indian George, be taken by the said Sheriff or his lawful deputy of successor in office, on the day and between the hours in that he has last aforesaid, from the place of confinement to a gallows, to be by said Sheriff for that purpose erected at Jacksonville, in the county of Jackson, and there to be hanged by the neck, until you, Indian George, be dead and may God have mercy on your soul. "The Beginning of the Rogue River War--The Murder of the Indian Boy, etc. etc.," Ashland Tidings, October 25, 1878 A full transcription of the district court docket is here. On the sixth day of February [1854] a new judge called court. The enemies of Judge Deady had been busy at Washington, it is said, and by the most gross misrepresentation procured his displacement, the executive appointing O. B. McFadden, a citizen of Pennsylvania, to the territorial bench. Court was held in a building next to the "New State " saloon, and it was a most unpretentious temple of justice. The bench was a dry-goods box, covered with a blue blanket, and it is quite probable that the uncomfortable seat occupied by the judge was so irksome that it had something to do with his rapid dispensation of justice. The officers of the court were Columbus Sims, prosecuting attorney; G. Kennedy, sheriff; and Lycurgus Jackson, clerk. On the first day of court, Paine P. Prim and D. B. Brenan were admitted to the bar, and the grand jury was empaneled. On the seventh, true bills were returned against Indians George and Tom, charging them with the murder of James C. Kyle, on 1853; October 7 [sic], on the same day they were arraigned and put upon trial, Prim and Brenan having been appointed counsel for the accused. The proceedings were brief, the evidence, mostly that of Indians, who were anxious to preserve peace with the whites, left no doubt as to the guilt of the prisoners, and the jury, with little deliberation, announced a verdict of guilty. In the meantime the grand jury had found another indictment against Indian Thompson, for the murder of Edwards in the spring of 1853, and he, too, was quickly convicted. On the ninth, it appears from the record, Indian George was sentenced to be "hanged by the neck until dead," the time of execution being fixed between the hours of ten and twelve of the succeeding day; but it does not appear that the other two convicted murderers were ever sentenced; and the impression is left that time was so valuable that, in their cases, the formality was dispensed with. In passing sentence upon George, his honor assured the prisoner, with becoming gravity, that he had had as fair a trial, and as ample means of defense, as if he had belonged to the white race; but the lightning speed with which the judge hurried the doomed wretch out of the world throws a slight cloud on the sincerity of his remarks. Indeed, it can not be fairly doubted that if the murderer had been a white, he would have been granted thirty days for repentance; but his honor probably concluded that the Indian had no soul, and repentance was therefore improbable, although he closed by requesting God to have mercy on the spiritual portion of the culprit. Though the record is silent as to the other two convicted murderers, all three were swung from the same gallows on the tenth of the same month. Large numbers of people came from the mining camps, and a few, whom the news had reached out in the valley, came into town to witness the first legal execution, but the event was marked with decorum, and nine out of ten acquiesced in the justice of the punishment. This was the last court held in Jacksonville by Judge McFadden. Judge Deady's friends had righted matters at Washington and procured his reinstatement, McFadden being transferred to Washington Territory. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 366 Very soon after the construction of the military post was resolved upon, a circumstance occurred which ranks as one of the most important, and at the same time singular, that we have to narrate. This was the murder of James C. Kyle, on the sixth of October, 1853, by Indians from the Table Rock reservation. This sad affair took place within two miles of Fort Lane, at a time when the settlers were congratulating themselves that Indian difficulties were at an end. Kyle was a merchant of Jacksonville, partner of Wills whose untimely and cruel death has been recorded. A rigid examination and investigation of the homicide proved that it was committed by individuals from the reservation, and the chiefs were called upon to surrender the criminals in compliance with the terms of the treaty. They did so, and two Indians, George and Tom, were handed over to the proper authorities, as the murderers of Kyle, while Indian Thompson, tillicum of the same tribe, who has been previously mentioned, was surrendered as the murderer of Edwards. Like Thompson, the other two suspects were tried before Judge McFadden of the United States circuit court, at Jacksonville, in February, 1854. They were found guilty, and hanged two days later. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 231 On the fourth of August [1853] the first act of the new era of hostilities took place, being the murder of Edward Edwards, an old farmer, residing on Bear Creek, about two and a half miles below the town site of Phoenix. In his absence the murderers secreted themselves in his cabin, and on his return at noon, shot him with his own gun, and after pillaging the house fled to the hills. There were but few concerned in the deed, and subsequent developments fixed the guilt upon Indian Thompson, who was surrendered by the chiefs at Table Rock, tried in the United States circuit court in February, 1854, and hanged two days later. According to the prevailing account of the circumstances of this murder, the deed was committed in revenge for an act of injustice perpetrated on an Indian by a Mexican named Debusha, who enticed or abducted a squaw from Jim's village, and when the chief and the woman's husband went to reclaim her they were met by threats of shooting. Naturally disturbed by the affair, the aggrieved brave started upon a tour of vengeance against the white race, killing Edwards and attempting other crimes. Colonel Ross, a prominent actor in the events that followed, identifies the murderer as Pe-oos-e-cut, a nephew of Chief John, of the Applegates, and represents the difficulty substantially as above stated, adding the particulars that Debusha had bought the squaw, of whom the Indian had been the lover. She ran away to a camp on Bear Creek, and the Mexican, with Charles Harris, went to the camp and took her from Pe-oos-e-cut, much to his anger and grief. The disappointed lover next day began venting his rage against the whites by killing cattle and also shot Edwards as described. No sooner had the murder become known, than other savages became imbued with a desire to kill, and during the following fortnight several murders were committed, through treachery mainly. A. G. Walling, History of Southern Oregon, 1884, page 213 ----

Unknown: J. H. Williamson, a prominent flour manufacturer of Muncie, Ind., has been visiting in Jacksonville, accompanied by his wife; the guests of Mrs. E. J. Kubli. Mr. W. is a brother of Mack Williamson, who was killed by a Spaniard in early days and whose murderer was lynched by citizens.

"Personal Mention," Democratic Times, Jacksonville,

June 15, 1899, page 3

"Do you remember the Spaniard that killed Alex Williamson?" asked one of the group. "Williamson was foreman of a pack train. A Spaniard driving for him stabbed him, thinking he would be able to get away, but by the merest chance another pack outfit came in sight of the camp just as the murder occurred. They caught the Spaniard, put a rope around his neck and threw the rope over a tree and pulled away. The Spaniard, whose hands were not tied, grabbed the rope above his head and began climbing up. One of the packers grabbed him by the legs and brought him down with a jerk, and hung to him until he had strangled to death. It was swift but sure justice." Fred Lockley, "A Town That Lives in the Past," Oregon Journal, Portland, November 24, 1912, page 63 ----

George M. Bowen, 1860: MURDERER TO BE HANGED.--James W. Bowen, convicted by the Circuit Court of Jackson County, Southern Oregon, for murder, has been sentenced to be hung on 19th August. San Francisco Bulletin, July 25, 1859, page 3 Geo. M. Bowen, convicted of the murder of a Chinaman at Jacksonville, Oregon, was sentenced to be hung on the 10th February next. "The Overland Mails: Yreka," Los Angeles Star, January 28, 1860, page 3 THE GOVERNOR OF THE STATE OF OREGON, To L. J. C. Duncan, of Jackson County, in said State, George M. Bowen, now under sentence of death, and of said County and State, and to all others to whom these presents shall come, greeting: KNOW YE, That a petition has been presented to me praying for a commutation of the sentence pronounced against the said Bowen from death to imprisonment for life, and that accompanying said petition are copies of the indictment and evidence used by the State on the trial of the said Bowen; .also, the affidavit of Robert Opp, touching the mortality of the wounds inflicted on the deceased Chinaman of whose death the said Bowen stands convicted. Now, after having had the aforenamed papers under strict advisement, noting the fact that no post mortem examination, or coroner's inquest were had, and that no Physician was called to testify as to the extent of the injury done the said Chinaman by the wound inflicted, we are of the opinion that common justice would demand that evidence going to show that the deceased Chinaman did not necessarily die from the effects of said wounds, and that if proper care had been given, death need not have ensued therefrom, should be fairly considered by me. Therefore, for these and other reasons, and to the end that strict justice may prevail, be it known, that I, John Whiteaker, Governor of the State of Oregon, do issue this my warrant unto you the said L. J. C. Duncan, Sheriff of Jackson County, and George M. Bowen, now under sentence of death, directing you, the said Sheriff, to stay the execution of the sentence of the court from the tenth day of February, 1860, to the ninth day of March of the same year, when if no other order shall have been made, you, the said L. J. C. Duncan will proceed to execute the sentence as already directed by the court. In testimony whereof I have hereunto signed my name and will cause the seal of the State to be affixed this 1st day of Feb'y., 1860. By the Governor, JOHN WHITEAKER. LUCIEN HEATH, Secretary of State. Journal of the Proceedings of the Senate, begun Sept. 10, 1860, Salem 1860, Appendix, page 6 Geo. M. Bowen, whose execution, for the murder of a Chinaman, was to have taken place at Jacksonville, Oregon, on Friday last, has been respited until the 9th of March, by Governor Whiteaker. "Telegraphic," The Daily Appeal, Marysville, California, February 13, 1860, page 2 THE GOVERNOR OF THE STATE OF OREGON, To George M. Bowen, of Jackson County, in said State, and now under sentence of death, and to all others to whom these presents shall come, greeting: KNOW YE, That a petition praying for a commutation of the sentence pronounced against the said George M. Bowen from death to imprisonment in the Penitentiary for life, has been presented to me, which petition is signed by numerous good citizens of Jackson and Josephine counties, in this State, among whom are the attorneys for the State in the trial and conviction of the said Bowen, the sheriff of Jackson County, the clerk of the court in which the trial was had, and a part of the jury who sat upon the case, as well as many other citizens whose characters entitle them to respect; and, Know ye further that said petition was accompanied by the affidavits of Robert Opp, Jerome A. Epperson, E. D. Brown and Paul McQuade, the last three of whom were not witnesses in the trial of the said Bowen, all of whom testify and say that in their opinion the wound inflicted on the deceased Chinaman, and charged in the indictment, was not sufficient to produce death if reasonable care had been given; and there having been no post mortem examination, or coroner's inquest held on the, body of the deceased Chinaman, or physician called on the trial to testify as to the extent of the injury inflicted by the said Bowen on the deceased Chinaman, or the mortality of the wound charged in the indictment; Now, for these reasons, I have deemed it to be my duty to interpose and stay the too rigorous hand of the law; and in the exercise of the power granted by the Constitution of this State to its Executive, and in conformity with the laws of the same, I, John Whiteaker, Governor of the State of Oregon, do grant the petition of Geo. M. Bowen, now in prison in Jackson County, in this State, and under sentence of death, commuting his sentence to that of imprisonment in the Penitentiary of this State, at hard labor, for life, with the following conditions: That if the said George M. Bowen shall escape, or attempt to escape from his guards, keepers or other persons having him in charge, or from any prison in which he may be lodged under the provisions of this warrant, or shall be found at large anywhere within the limits of this State, he shall forfeit all the rights and privileges granted by this commutation, and shall be held to have escaped while under sentence of death; and it is hereby directed that all persons interested in the execution of the sentence pronounced against said Bowen, or in anywise interested in the custody of his person, as well as the keepers of the Penitentiary, that they take this provision of this warrant strictly in charge, and assist in carrying out the same; Provided, That nothing herein contained shall be so construed as to deny the right of the said Bowen to elect between the sentence of the court, as modified by the respite of the Governor, and the provisions of this commutation. , In testimony whereof, I have hereunto signed my name, and will cause the seal of State to be affixed, this 1st day of March, 1860,. By the Governor, JOHN WHITEAKER. LUCIEN HEATH, Secretary of State. Journal of the Proceedings of the Senate, begun Sept. 10, 1860, Salem 1860, Appendix, page 7 Geo. M. Bowen, convicted of killing a Chinaman in Jackson Co., and sentenced to be hung, was respited by Gov. Whiteaker. His friends are making an effort to commute his sentence to imprisonment for life.… "Domestic Items," Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 6, 1860, page 2 COMMUTED.--The sentence of Geo. M. Bowen, convicted of killing a Chinaman some time since, has been commuted from death to imprisonment for life in the penitentiary. The Governor acted thus in answer to the petition of over 600 citizens. The provisions of the commutation are--that if the prisoner escapes, or is found at large within the limits of the state, then he is subject to arrest as an outlaw, and the original sentence of death will be executed upon him. The Oregon Argus, Oregon City, March 24, 1860, page 2 George M. Bowen, whose sentence was commuted from hanging to imprisonment for life for robbery and murder of a Chinaman, reached the penitentiary last week in charge of the deputy sheriff of Jackson County. The fellow richly deserved hanging. He had lived, as we are informed, by robbing Chinamen, for some time, and at the same time the murder was committed for which he was tried and sentenced, he with others attacked a party of Chinamen for the purpose of robbing them. The Chinamen resisting, one of their number was killed by Bowen, but finally they succeeded in overpowering their assailants and succeeded in capturing Bowen, whom they sewed up in a blanket and carried to Jacksonville. His accomplices escaped. "Domestic Items," Oregon Statesman, Salem, March 27, 1860, page 2 We have too many gamblers, blacklegs and loafers in our midst. There are too many shooting affrays left almost unnoticed, too many murders committed, and the guilty go unpunished. The above-mentioned class of men have too much to say in our courts of pretended justice. No longer ago than last week the deputy sheriff of this county was circulating a petition for the commutation of Bowen's sentence, who was to have been hung on the 10th inst., but his time was prolonged by the Governor, to give them time to get all the signers possible. Bowen, in attempting to rob a Chinaman of his money, killed him, and now a great many say he ought not to be punished for killing a defenseless Chinaman. It seems to me a cowardly act, which he knew he could commit with impunity and run no risk of losing his own life, unless by the execution of the law, which he is about to avoid by the help of many interested friends. I hope, however, that our Gov. will not be blinded on this matter, but let him pull hemp. Everything is ready, the gallows built, the coffin made, the rope purchased and everything in readiness for the execution and interment. Letter dated February 26, 1860, Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, March 27, 1860, page 1 On the morning of the 19th, one of the guard at the Penitentiary took out three convicts named George Bowen, Joseph Underwood and Tom Langdon--the first and last of whom were sentenced for life, and the other for two or three years--to work in the upper part of town on a ditch for Pentland's water works. Bowen took advantage of the guard, who had his hands in his pockets, by "mugging" him; that is, pushing his head down against his breast, while the other two disarmed him. They then fled. "Late from Oregon," Sacramento Daily Union, March 30, 1861, page 4 From the Crescent City Herald, May, 1861.

We learn

that on Saturday, May 5th, Deputy Sheriff George Morris, of Happy Camp,

in this county, received information that the notorious George Bowen,

an escaped state prison convict, with a companion, was seen crossing

the Siskiyou Mountains, traveling towards the Klamath River

settlements. Morris summoned a posse, and the party, consisting of the

Deputy, T. Maloney, Chas. Lang and Jas. Benjamin, started out to

capture the men. About daylight, Bowen's companion came out from a

cabin that the posse had been watching. The sheriff warned him not to

make any resistance, but the man paid no heed to the command, leveling

his pistol at the head of one of the posse, when the Sheriff shot him

down. Bowen rushed out of the cabin with a cocked pistol in either

hand, one of which he leveled at the Sheriff’s head, who, however, was

too quick for him, giving him the contents of the remaining barrel, and

planting eleven buckshot between his shoulders, who fell dead in his

tracks. His companion lived about twenty minutes after he was shot.

Many of our citizens will doubtless recollect this man Bowen, as he was

at one time an inmate of our county jail, on a charge of robbing some

Chinamen, but got clear by turning state's evidence. We next heard of

him in Jackson County, Oregon, where he murdered a Chinaman, for which

crime he was tried, found guilty, sentenced to be hung; but the

Governor commuted the sentence to imprisonment for life, with a

provision, however, that should he make his escape from prison and be

retaken the original sentence of death should be carried out.Geo. M. Bowen, the escaped convict and murderer, was shot dead on Monday, about ten miles above Happy Camp, Del Norte County, by the deputy sheriff. Bowen's partner, a Mexican, was also killed by the officer. They were armed with three revolvers and a knife. "From Oregon," Red Bluff Independent, May 21, 1861, page 3 On the 5th of May, Deputy Sheriff Morris, of Del Norte County, killed the noted Geo. Bowen, highwayman, and another desperado, name unknown. Bowen was an escaped state convict. He had been sentenced to hang for murder in Oregon, but the Governor commuted the punishment to imprisonment, conditionally that he should suffer extreme punishment in the event of his escape and recapture. "By Telegraph to the Union," Sacramento Daily Union, May 21, 1861, page 2 From the Crescent City Herald, June, 1861.

We supposed after

Deputy Sheriff Morris had given Bowen his quietus on the Klamath so

effectually, that we should hardly hear of him again. But a party

entering a cabin, supposed to be deserted, on Althouse lately, found a

Chinaman suspended by the neck, in which position he appeared to have

been for about two weeks. It was doubtless the work of Bowen.FILLING ANOTHER MAN'S GRAVE.

BY THE EDITOR.

We had a good

many roughs in Southern Oregon twenty years ago, just such fellows as

afterwards adorned the pines of Idaho and Montana, and there is a

little bit of history connected with one of them that seems to

substantiate the doctrine of total depravity and shows that an empty

and unowned grave may not be without its uses. His name was George M.

Bowen, but more a coward than a desperado, and his game was principally

the plunder of Chinese miners. Bowen claimed to be an "honest miner"

himself, frequently coming into town for small supplies and for a long

time was unsuspected of being merely a thief. He played his game of

Chinese tax-gatherer long and successfully, and probably too cowardly

to attack nobler game, he shrewdly confined his operations to that

docile race. At last the Chinese became tired of the repeated and

exorbitant levies on their industry. Bowen haunted them by day and by

night, like an evil spirit, and hardly a camp on Applegate escaped his

vigilance, and he became a terror to the whole Chinese population of

that stream. At last, emboldened by success, Bowen attacked a large

camp near O'Brien's and demanded tribute, but the Chinese resisted and

in the struggle one of them was killed by the highwayman. A desperate

but strategic onset was now made and Bowen, tripped by a rope in the

hands of about a dozen of Chinamen, was disarmed, wrapped in a pair of

blankets like an Egyptian mummy, brought to Jacksonville by his captors

and delivered to the authorities. There seemed to be little doubt of

Bowen's guilt, and his face, stamped with the hoof of sin, would have

convicted him. It was an ill-looking, a selfish, cruel and

hard-featured face, and when brought before Recorder Hayden it was

still covered with the lampblack used to disguise it. Waiving an

examination, the robber was committed to jail on a charge of murder and

his trial set for the July term in 1859. When the case came up, Reed

and Burnett appeared in behalf of the prisoner, but after an able and

determined effort their client was fairly convicted and sentenced by

Judge Prim, now on the supreme bench, to be hanged on Friday the 19th

day of August [sic]

in that

year. Murder had been too frequent, conviction too uncommon, and it was

felt that the spirit that prompted violence to the Chinese would grow

bolder in time if unrestrained. The prisoner's counsel were alone

dissatisfied. With a just professional pride they had made a gallant

fight to save his worthless neck and, determined that it should not be

broken, they renewed it by carrying the case to the supreme court on a

writ of error. The court, then composed of Aaron E. Waite, Chief

Justice, and Boise and Prim associates, carefully considering the case