|

|

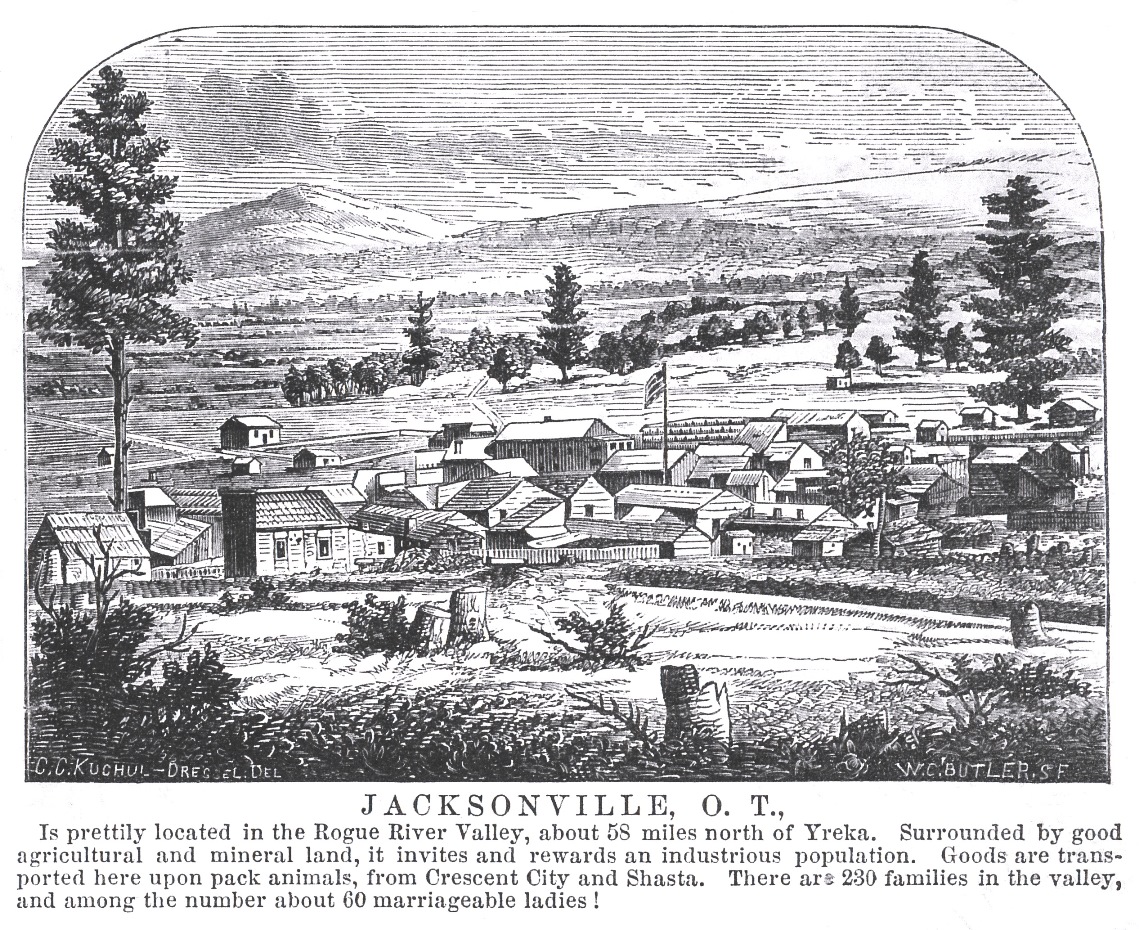

Jackson County 1855 Travelers' descriptions and assessments of the state of things. For a visit to the South Coast from Crescent City to Coos Bay in October 1855--on the brink of war--click here. Also refer to Capt. T. J. Cram's report.  Jacksonville 1855,

by James Mason Hutchings

From Columbia River to Cape Blanco.--The name Blanco appears to have been applied before "Orford," and moreover very well expresses the appearance of the cape. The bluff is about a hundred feet high, and nearly perpendicular, with whitish sides. The top is covered with trees, which give it the appearance of an island in making it from the north or south, the neck and some distance back to the main being destitute of trees. This line of coast is nearly straight. Tillamook is a bold, prominent, and readily remembered and recognized headland, at the southern termination of the long sand-beach, running from Point Adams. From Tillamook the coast presents a country well watered by numerous small streams emptying into the ocean. It is densely covered with timber, and for a few miles back looks favorably from the deck of a vessel. The Tillamook Bay is said to be several miles in length, but the entrance is such that it can be made only under the most favorable circumstances, there being very little water on the bar. Between Tillamook and Coos Bay the country (excepting the headlands shooting into the ocean) appears low, and well watered for many miles back, but vessels cannot approach from the sea. North of the Coos is Umpqua River, the largest stream between the Columbia and the Sacramento. The entrance is long and narrow, with about thirteen feet of water on the bar at low tide. This river is said to drain an extremely fertile region, well adapted to agriculture and grazing, and abounding in prairie land. The valley of the Umpqua is filling up with settlers. Coos Bay has a wide, well-marked entrance, but the bar has but nine or nine and a half feet water on it at low tide. The coal once alleged to exist here is now pronounced a lignite, and cannot be used as fuel. The geology of this section does not give any promise of coal. I have been informed that vessels anchoring close in with the bluff between Cape Arago and the Coos bar may ride out heavy southeasters; and if so, it is important, no other place between Sir Francis Drake's and Neah Bay affording that facility. The Coquille River, entering about fifteen miles south of Cape Arago, has been followed a distance of thirty miles, giving a depth throughout of not less than fifteen feet, and an average width of forty yards. It drains a very fertile region, abounding in many varieties of timber. Numerous Indian encampments are found upon its banks, and quite extensive fish-weirs. When off the entrance last year we saw about a dozen houses which had been built by the miners then engaged in washing the auriferous sand and gravel found on the beach between that point and Rogue's River. A small stream (Sixes River) empties into the ocean a mile north of Cape Blanco. A preliminary survey of the reef off Cape Blanco has been made, showing its relative position and the passage through it. In the country near Port Orford is found the finest white cedar, and, so far as I know, this is the only locality in which it occurs along the coast. Port Orford is the best summer anchorage between Drake's Bay and the Columbia. It is about seventy miles distant from the mines in the interior, and on the opening of a road would become a large depot of supply. Rogue's River, so called from the character of the Indians inhabiting its banks, deservedly merits the appellation. One vessel has entered, was attacked, deserted, and was then burnt by the Indians. The water always breaks upon the bar, and the reef off the entrance demands attention. Illinois River.--The naming of this river is made merely upon the guess of some miners and settlers at its mouth, which they had reached by following the coast from Crescent City. The river is fifty or sixty yards wide, deep and sluggish, else it would, during summer, force its way through the gravel-beach at its mouth. Indian huts in great number appeared on the banks, but most of the occupants were then engaged higher up the river in taking salmon. Smith's River.--The entrance of this river I looked for in vain from the deck of the vessel, though scarcely two miles from the shore, and I was able to form a pretty good estimate as to where it should open. The "Smith's River" of the maps is a myth. The reef of the coast hence to Crescent City, like the Rogue's River and Blanco reefs, demands an examination. Crescent City.--The anchorage is rocky and uncertain. The beach is low and sandy. Klamath River.--The mouth of this river was closed in 1851. I believe one or two vessels have entered it. Trinidad Bay affords a safe anchorage in summer. The land in the vicinity is very rich and well adapted to agriculture. Redwood trees grow in this vicinity, and attain an enormous size. The stump of one which we measured was about twenty feet in diameter, and a dozen in its vicinity averaged over ten feet. One is said to be standing on the bank of a small stream on the south side of the bay that will measure thirty-two feet in diameter. The trees are quite straight, branch at fifty to a hundred feet from the ground, and frequently attain a height of two hundred feet. A forest of redwood presents a magnificent sight. Mad River empties about a mile above Humboldt Bay. Egress is shut out by the breaking on the bar; but the vast amount of lumber in its valley will soon find an exit through a canal to Humboldt Bay. A deep slough from the latter approaches quite close to Mad River, near its mouth, thus favoring the execution of such a project. I am informed that the river averages a hundred yards in width. George Davidson, "Appendix No. 26," Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 34th Congress, Ex. Doc. No. 22, USGPO 1856, pages 179-180 Emigrant Road--Northern Route.

The Yreka

Herald of the

6th inst. copies an article from this paper upon the emigrant road,

and over the plains mail stage route, in which state aid is invoked to

open roads over the Sierra Nevada, and to survey a route and locate

posts from here to Salt Lake, and gives the following observations upon

the extreme northern route. We were aware, from the reports of those

who have traveled it, that the pass into Siskiyou was one of the most

favorable yet discovered in the Sierra range, but that, after teaching

Yreka, it was next to impossible to get from that valley to the

Sacramento with a wagon. Whenever a good wagon road is completed from

Yreka to Shasta, that route will doubtless be extensively traveled by

those wishing to reach the head of the Sacramento Valley, or who intend

to locate in the rich mining region in Siskiyou, as well as by

emigrants desiring to settle in Southern Oregon. When the

subject comes fairly before the Legislature, this extreme northern

route will be sure to receive its full share of attention. We

copy from the Herald:The above recommends "the improvement of at least three routes across the Sierra Nevada," and the "establishment of such trading posts and military stations as may be deemed necessary to supply and protect the emigrants." Now, in the north we have a route over which emigrants may reach California without any repair or outlay on the trail over the Sierra Nevada. There is no high mountain to cross, the ascent and descent, with the exception of about one fourth of a mile, is scarcely perceptible. The distance is not so great as that over any other northern route, and the entire road from the Humboldt abounds in the most luxuriant grass and good water. All we want on this route is the establishment of a military post on Clear Lake, and another on the Humboldt, to protect the emigrants from the Indians, and we have a route over which emigrants may reach this valley, the rich valleys in Southern Oregon on our north, or the Sacramento Valley on the south, without the necessity of losing a hoof of stock in consequence of bad road in want of food and water between here and the Humboldt. By the arrival of the next emigration, the wagon road between this place and the Sacramento Valley, via the Whortleberry Patch, will be completed, which will connect the great valleys of the Pacific. The emigrant trail intersects this road at Mount Shasta, and will ultimately be the route over which nearly all the stock and much of the emigration from the East, destined for the Sacramento Valley, must pass. The road across the Sierra Nevada, past Goose, Clear and Klamath lakes, and into Shasta Valley, is the only route into California on which good feed can be obtained all the way from the Humboldt, and on which the crossing of the Sierra Nevada is no obstacle. The rich and extensive mineral and agricultural resources of Siskiyou, Klamath and Trinity counties, in California, and Jackson County (or the Rogue River country) and the Umpqua ini Oregon, to which this road leads directly, and its many other superior advantages over every other route, cannot fail hereafter to make it one of, if not the greatest, thoroughfare across the Sierra Nevada, and one which can be traveled at all seasons of the year. Sacramento Daily Union, January 13, 1855, page 2 Wagon Roads.

Good roads and a ready communication

from one section of the country to another belong necessarily

to

civilization. Barbarous nations are invariably found destitute

of. roads, or artificial means of communication. The ancients built

roads for military purposes, but for none other. The moderns build them

as necessary to extend commerce, expand its influences, and furnish

means of progress for humanity--for the million.In the mountain districts of this state, these arteries of the body politic depend for their creation upon human skill, capital, and energy. Nature had left the face of the country rough, rocky, and mountainous, but at the same time she has deposited under those mountains treasures of that gold which is another great civilizer of the race, and which the natural and artificial want of man force him to seek, at the expense of great labor and toil. Good roads, however, reduce this toil, and assist in developing the mineral wealth embedded in the mountains of California. Probably no portion of the state has been so severely taxed for lack of roads as the northern. The people there are literally without roads. Since its first settlement supplies have been furnished by means of the pack mule, and communication between points maintained by means of the same animal and "trails." For a few months past, the people in those regions have been striving to relieve themselves from these difficulties. Plans have been proposed for opening roads from Crescent City to Yreka, from the latter place to Shasta; from Shasta to Weaverville, and from Humboldt also, over into the eastern valley. There may have been others spoken of which have escaped our notice. But we have named enough to exhibit the intense interest which prevails in the northern portion of the state upon the subject of roads and turnpikes. Most of the enterprises projected would, we have no doubt, pay a first-rate interest on the money invested to build the roads, but the sparseness of the population in those counties renders it difficult to raise the amount of money requisite, and unless assistance can be obtained from individual capitalists in the more densely populated portions of the state, or from the state herself, there is danger that most of these enterprises will fail. So important do we conceive these road enterprises in developing the resources of the state in social, commercial, agricultural and mineral wealth, that if any plan can be devised by which the state can constitutionally aid, we should favor its adoption. The principle of aiding the building of good roads by means of state aid is founded upon the arguments which apply in favor of state aid for railroads and canals. The only difference is in degree. Our attention has been called more particularly to this matter by an article we find in the Crescent City Herald, and in reading the report of the engineer who surveyed a route for a turnpike road from that point over the Siskiyou Mountain, by means of which a good line of wagon communication would be opened from Crescent City to Yreka. Of the distance, cost, &c., the Herald says: "Between Crescent City and the fertile valleys of Northern California and Southern Oregon interposes the Coast Range of mountains, which is well known to extend all along the northern Pacific shore. In our neighborhood this mountain range is comparatively low and presents regular ridges over which a good road, only forty miles in length, may be carried into Illinois Valley. At present but a mule trail leads across the mountains, over which, during the year of 1854, not less than 4000 tons of merchandise have been carried at the rate of seven cents per pound or $140 per ton--making the enormous amount of $560,000 paid for freight. A wagon road would at least save half that sum. Is it to be wondered at that a company was formed under the provisions of the statute to construct a turnpike road? The company incurred an expense of over $2000 for a scientific survey of the route. The detailed report of the engineer is before us; the road is practicable at a maximum grade of one foot upon ten, and the greatest elevation reached is 3,567 feet above high tide water. A turnpike road eighteen feet wide can be constructed for some $85,000 on the present survey, while some of our citizens are sanguine that further explorations will show us a still easier and perhaps less expensive route." Upon the policy of expending money on the part of the state for opening roads in various parts of the state, and particularly over the Sierra Nevada, the Herald remarks: "We are a young state yet, and the country to a great extent devoid of good roads. A couple of millions judiciously expended in the construction of roads would double the taxable property in the state, and facilitate very much the acquisition of wealth and comfort to our citizens generally. It is neither wise nor necessary that the present should do everything, and hand down to the future a country adorned and provided with all the improvements and appliances of civilization entirely unencumbered. Those that will come after us will be able to pay tolls and taxes as well as we are, and even more so." It then proposed, in order to cover, as it were, the state with a network of good roads, that she lend her credit to the amount of two millions of dollars for that purpose. This plan is impracticable, simply because the constitution forbids it. One of the suggestions of the Herald to raise money to build their turnpike may meet a favorable consideration at the hands of the legislature. That body we believe is disposed to do all which can be done through the agency of the state towards furnishing good roads over the Sierra Nevada, as well as in other portions of the state. The Herald's suggestion is-- "That by an act of the legislature, Crescent City, as a corporation, on a two-third vote of her citizens, be authorized to subscribe $60,000, or an amount not exceeding two-thirds of the capital stock in an enterprise having for its object the construction of a turnpike road from Crescent City to Illinois Valley, and undertaken by citizens of this state in accordance with and under the provisions of the act passed May 12th, 1855, 'To authorize the formation of corporations for the construction of Plank or Turnpike Roads,' and that the city may thereupon issue bonds of $500 each, bearing 10 percent interest per annum, redeemable ten years after date." The road from the head of the Sacramento Valley to Oregon, by way of Shasta and Yreka, may be classed as a United States Military Road. In the event of a war, and the blockade of our ports, such a road would become of commanding importance in defending Oregon and California. In this view, the funds to build it should be furnished by the United States government. Further efforts may therefore be made with propriety to obtain from the United States an appropriation to assist in building this road. The company proposing to build it, in consideration of a certain sum, would guarantee its free use for government purposes for all time. Sacramento Daily Union, February 3, 1855, page 2 Cloudy and warm. From South Mountain House to "Eden" School Dist., Rogue River Valley, 22 miles. Had pretty good quarters last night at Cole's (M.H.). [illegible] Bear Valley is two miles north of Mountain House, from Cole's to Rogue River Valley--a distance of about 14 miles--the road is very heavy and clayey mud. The horse's feet when drawn out go off like corks from large bottles, such is the suction of the mud. At other times the water from an old hoof hole would squirt 6 or 8 feet above one's head when on horseback. Plug! Plug! Plug! would be the music. From Yreka to the Siskiyou Mountains there is but little timber (except in the distance), but having reached the summit in descending towards the Rogue River Valley the forest timber is very heavy and dense. How a stage gets over that road I can't say upon oath. I know that it was as much as my horse wanted to do to get along without my riding. When you get a distant view of the Rogue River Valley you are struck with the beautiful green slopes and clumps of oaks and pines on a rounding knoll here or there with the smoke curling up from one of those woody dwelling places. The mountains too (although on the northeastern side of the valley one without heavy timber) are beautiful from their singularity of shape and evenness of surface. The climate of this valley must be more moist than in California, as I see the grass roots do not die here from excessive drought, while every hill has a number of animals grazing on the top, for the grass is good although the snow has not been off the ground over a month. Met a lady sitting astride her mule the same as the two men with her. She didn't exhibit much of the beauty or ugliness of her understandings. I must say I like to see a neat ankle on a woman! She had one, and I of course had to admire, consequently, looked! The Siskiyou Mountain is easy and gradual of ascent and not very high. Met several pack trains laden with goods for Yreka, they having come by way of Crescent City and Jacksonville. Now, as the Rogue River Valley opens to the view, how beautifully diversified is the scene--with fine clear openings of rich, black soil just turned up by the plow, now the young wheat fresh and green peeping from the soil; here and there a small stream running down from the timber-clothed mountainside that would turn a mill or color the flower or give vitality to crops, here a small swell of land covered with oaks, there one of pines, yonder another with that beautiful evergreen the "manzanita" and other bushes. February 6, 1855 Cloudy--rain & cold in the morning--not much better evening. From "Eden" (or "Rockfellow's Tavern") R.R. Valley to Sterlingville, 12 miles. Was only charged $3.00 for myself and horse for last night!!! Good. Kept a-wending my way 'round fences and houses for about 4 miles further down the valley, when I left it following a trail towards Sterlingville, a much higher and more difficult mountain to climb than coming over the Siskiyou Range. Grass on every hill--good grass--and on the distant hills could see cattle grazing. Reached Sterling about 2 o'clock. This is a small town that has newly sprung up, the diggings not having been found more than 7 or 8 months, but there are now in the vicinity about 550 miners--about 20 families--no marriageable women--about 35 children. This is a busy little spot--the hillsides and gulches are alive with men at work either "stripping" or "drifting" or "sluicing" or "tomming" or draining their claims by a "tail race." Yet the water is thick with use, being very scarce, as a large number of men are using it. Here you see a prospector with his pick on his shoulder and a pan under his arm, and his partner coming along with the shovel upon his shoulder. That man yonder with the blankets at his back has just got in--he is now asking if you know anyone who wants to hire him. You tell him where you think he may live for a few days, and when that fails he will have money enough to buy himself some tools and set himself to work. There as everywhere the cry is water--water--"will it never rain"--yes--"they feel dull enough" for they can't make their board for want of water. They ask you "if the people at Yreka are doing anything yet?" "No," is your answer. They want water, the canal not being finished yet. Things are duller there than here. "Had I seen anything of a man named Brooks who was coming to see if he couldn't bring Applegate Creek to set the men doing something with the water?" No, I hadn't. "Well, he was a-coming." That's the talk, said I. This town is situated on Sterling Creek about 5 miles from its junction with Applegate Creek. The creek is about 8 miles long. February 7, 1855 Cloudy & a few drops of rain Down Sterling Creek to its mouth called Bunkumville [Buncom], 5 mi. Left Sterlingville to go down the creek for about a mile and quarter down. On the hillsides men are very busy the same as in town; many are doing remarkably well with the little water they now have. There is but little mining in the creek. Then further down you go for 2½ miles before you see anything being done--not a man to be seen--then a prospector or two, then a couple of men at work, then a company, then more prospectors. Then cabins are seen and in the distance a flag--perhaps a piece of old canvas tied to a pole (although sometimes the stars and stripes are floating proudly as if to say "walk in--there's liberty here--to get drunk if you have money or credit"). At all events it indicates a trading post. Opposite to that the rocks and the water and the pick or the shovel or the fork are rattling in or about the sluice boxes. People are all hard at work. What a contrast to some places. As I was looking and thinking how much these diggings resembled White Rock in El Dorado Co., a voice hailed me, "Why, how do you do Mr. H!" and a hearty grip of the hand from Jim Lamar, a man who worked for us at White Rock. It was rather a singular coincidence. The gold here is generally rough, not having been washed smooth by rolling as in some districts. I prophesied good hill diggings here same as at White Rock. February 8, 1855 Cloudy and dark. Rained ¾ an hour last night. Sterlingville. Last night it rained for about ¾ of an hour, and as I felt it pattering on my head I didn't approve of such an unfeeling course. I however moved further down in bed and covering my head with the blankets told it to rain on--but it didn't for long. Still it is an unpleasant situation, sleeping in the best hotel! of the place to find that when the rain can get at your head you feel its cold "fingers" down your back. Such is hotel accommodations here. There is moreover two women to cook, yet nothing fit to eat. Went without dinner rather than go to eat it. But then "they are from Oregon!!" The majority of the men here are those who crossed the plains last summer to Oregon and utterly disappointed had come on towards California. An inquisitive fellow inquired from me what state I was from. I told him I was a native of Pike Co. but had been raised in Oregon. "Oh! damn, damn, that must be hard" groaned he, but looking into my face he said, "I don't hardly believe you; it can't be." At this I burst out laughing and remarked that he must be from those "parts" to know that I was not!!! He then laughed and said "Get out!" Oregon people do not seem to be in good favor anywhere north. They are generally called "Wallah Wallahs," as a large portion talk the jargon of the Hudson Bay Co. February 9, 1855 Rained lightly all the morning, but held up at noon. From Sterlingville to Jacksonville, 8 miles. This morning it was rather unpleasant traveling in the rain; the road, however, is of a very gradual grade, but a large portion being through a timbered country, the roots across the road and on the ruts make it rather hard I should think for wagons. There are so many soft places near the roots and stumps a wagon has to cross. One fellow had taken himself up a ranch and was fencing up [i.e., across] the road--without in any way indicating any other way--and I accordingly got from my horse and threw down the fence at the trail. Men must be "darned" fools to suppose that strangers will spend their time hunting for a new trail when the plain one--with a fence across it--is just before him. I'll bet that fellow was from either "Pike" or "Oregon." It is too general sometimes turning teams a mile or two round and up a hard hill. About noon I reached Jacksonville

This is the county seat of Jackson Co.,

Oregon and was formerly called "Table Rock City."Diggings were first discovered near here in Feby. 1852 by Messrs. Clugage & Pool, who being on a prospecting tour found their labors rewarded by the discovery of good diggings. There were but three log houses in the Rogue River Valley then, for farming purposes. Messrs. C. & P. were digging a ditch to take water to the diggings. They had disc'd [discovered gold] and seeing some other men around discontinued work for about a month, but seeing the strangers about to locate they resumed their work and one and another would come and set to work and stay, hence arose the town so that now the population is about 700--22 families--and over 200 families in the Rogue River Valley. There are 53 marriageable [women] within a circuit of 12 miles of Jacksonville--9 within Jacksonville--35 scholars attend a day school kept by Miss Royle. Couldn't find the number of children in the valley. There are 10 stores, 3 boarding houses, 1 bowling alley, 1 billiard [saloon], 3 physicians (and 300 men called Doctor!), 1 tin shop, 1 meat [market], 1 livery stable--shame on it--1 church, 1 schoolhouse. February 10, 1855 Rain at intervals all day until evening, when it rained heavily 2½ hours. Jacksonville. This town is supported by the mines around and the wants of the agriculturalists. It is beautifully located in the Rogue River Valley about 10 miles above Table Rock. The houses seem mostly built of the tumble-down style of architecture. There is, however, one good brick store, built of lime [mortar] as it was dug out of the ground--natural lime. There seemed to me to be more Drs. by title than any other class. There seems a number of long-faced religionists--how blue and mean they look--they want credit, "hum" and "hah" and rub their hands and hang their head on one side as if deprecating their unworthiness to be a man--and so I should think they might, for a hog might suit their grubbing tastes better than the dignity of true manhood. I tarried at the Robinson House--the best building by far in town--went to bed about 1 o'clock, awoke by 3 men coming into my room. One lifted up the blankets to look in my face. "What's up?" I wished to know. "Oh, nothing." "Then don't you poke your nothings or your nose under my blanket anymore." "I was a-lookin' for a man." "Then why didn't you say so." Then in came 3 other men--all "liquored up." "Joe," said one, "hulloa, what do you want?" "I believe I am drunk--don't think I ought to be--do you Dr.?" (Everybody is Dr.) "Only had four 'cocktails.' I'm tight, sure I'm tight. Here, take my money." In the morning a gold watch was missing from another of the trio. They couldn't make it out. "Do you remember" (said the Dr.) "So and So offering to bet me his watch against mine that the sorrel mare would win? And I said, oh, no, mine is a better watch than yours. One of those fellows at the table must have taken it. Who were they? Why, there was Mr. _____ and Dr. _____ and Doc. _____" An inquiry was made from them and the barkeeper Dick and several others, but no gold watch or gold chain was forthcoming. By this time the one that confessed to being drunk found it underneath his hat upon the washstand, when downstairs he goes with the watch in his hand and saying that he thought that he was tolerably tight but he be blamed if the watch owner mustn't have been more so not to remember where he had put it. They then treated each other and were beginning to get a little tight again. This is the common failing of too many in Cal. February 11, 1855 Rain in morning, cloudy all day--except a few gleams of sunlight. From Jacksonville to North Mountain House, 22 miles. Anxious to avoid being rained in so far away from any point easily reached from our larger cities I started this morning and made along the Rogue River Valley, admiring its beautiful green slopes and timbered knolls. There are so many versions of the origin of the name of this valley, but I conclude the roguish disposition of the Indians is the true one--as seems more generally admitted. It is, however, a beautiful valley about 35 miles long and from ½ a mile to 20 miles wide and will average about 7½ miles in width. About 10 miles below Jacksonville is "Table Rock," a level and solitary elevation or rather elevations, as there are two, about 700 feet above the valley. Its length is about 350 feet by about 200 feet in width, at the base of which is situated the U.S. military post of "Fort Lane." It contains about 70 soldiers, and these have astonished and awed the Indians by throwing a shell to the top of Table Rock from the fort. This rock is a little east of north from Jacksonville. ----

Apples grown in

the Willamette Valley, O.T. were brought to Jacksonville in quantities

and sold wholesale at 90 cts. per lb. The small ones were retailed at

25 cts. each and the larger ones at 50 cts. each, but the largest sold

at a dollar. These were bought by Brown & Fowler of the El

Dorado

Billiard Saloon. These gents seem fond of fun, and they exhibit a small

pistol--old-fashioned and rusty--to the "Wallah Wallahs" or greenhorns

of Oregon as a pistol said to have been given to Rousset de Boulbon for

self-destruction on the morning of his execution. They also exhibit an

old broken and rusty cutlass as the knife with which the head of

Joaquin Murietta, the California bandit and robber, was cut off with!!!

and point out some deep rust as blood that has eaten into the blade!!!

These old "fixin's" were picked up in Crescent City, Ogn., brought on

here for a frolic by the express boys, who also brought some printed

notices with an expressman with the latest news on tap!!!!February 12, 1855 Cloudy. Rain in evening. From North Mountain House to Cottonwood, 29 miles. Oh, horrible--horrible has been the road today. The road over the Siskiyou Mountains had enough before, is now from the recent rains much worse. Mud Mud Mud; horse drawing long corks for 10 miles--now he would only be up to his knees, now again he would be up to his belly, almost pitching you over his head by the suddenness of the descent, or throwing you over his tail backwards when his forelegs are out and his hind ones are in the hole. This may have been a good stage road, but I wouldn't think so now--it is the worst road I ever traveled. Journal, 1855,

James Mason Hutchings papers, Library of Congress MMC-1892

Trip to Southern Oregon.

We have recently returned from a tour of six weeks, during which time

we have visited the greater portion of Southern Oregon. The country

lying below Corvallis, on the Willamette River, has been so often

described, and is so well known, that we shall not inflict upon our

readers a rehash of it. From Corvallis to the Calapooia Mountains, a

distance of some eighty miles, the country is diversified between broad

and rolling prairies and occasional belts of timber, principally oak,

pine and fir. On either side of the upper Willamette Valley, which

averages some fifteen or twenty miles in width, are the Cascade Range

of mountains on the east and the Coast Range on the west, whose rugged

crests and rocky summits present a bold and interesting as well as a

picturesque landscape of more than common beauty. The traveler or

admirer of nature's handiwork will find as he plods his way over these

extensive plains a constant changing of these distant views, with an

occasional glimpse through the notches of the mountains at some of the

numerous peaks, whose summits are covered with the eternal snows of

thousands of winters. This, together with the different appearance of

the sides of the numerous buttes

which extend from the mountains into the valley, present a diversified

appearance on the whole route."NOTINGS BY THE WAY." We found the country much more thickly settled than we expected to find it. The farms are generally half sections instead of 640 acres, which are so universally held in the lower valley. The soil is rich and productive, as is evidenced by the growing crops and the quantity of grass and vegetation which nature has abundantly spread over the whole surface of these beautiful plains. The first place of note above Corvallis, on the west side of the Willamette River, is Jennyopolis--where we found our old friend Dick Irwin, snugly located on a good farm with a good stock of goods, wares and merchandise, ready to trade or to receive his friends with a cordiality which makes the weary traveler feel as if he had found an oasis in a desert. Starr's Point, some distance further up, is located on Long Tom, a stream of considerable size, upon which there are good mill sites and other advantages which will make it, at no distant day, a densely populated country. Eugene City, the county seat of Lane County, is pleasantly located on high rolling ground, over which is scattered an occasional oak, as yet spared from the woodman's ax. There are adjacent to the town several large round mounds or hills of some one hundred feet in height, more or less. These hills are covered with scattering trees, which in the distance gives them the appearance of well-grown orchards. During our brief sojourn at Eugene City we had an opportunity of seeing the great majority of the people from the adjacent country, who came in to attend a public political meeting. The inhabitants appeared to enjoy the best of health, and carried the evidence in their physiognomies of possessing intelligence and happiness as well as thrift. There is at Eugene City an excellent hotel, kept by Heatherly & Bailey, where the wayfarer will find repose and quietness. From the number of stores and other places of trade we inferred there was considerable business done at Eugene City. From Eugene City to the Calapooia Mountains our route carried us over a fine farming and grazing country, well watered and timbered. Siuslaw can boast of one log house now, but may, in the future, number many more. A good day's ride carried us over the Calapooia Mountains, where we found a stopping place with Mr. Estes. The road over this mountain is comparatively in good order, and is one of the pleasantest mountain passes we have ever traveled in Oregon. There are but few difficulties in the way of calling it a good wagon road. Some of the ascents are rather steep for a common team to ascend with an ordinary load. After spending the night at Estes'--where we found a good bed and excellent accommodations--we left refreshed, and reached Jesse Applegate's at Yoncalla. Mr. Applegate is one among the early pioneers in Oregon, who has explored most of the mountain passes, rivers and forests throughout the length and breadth of Oregon in examining for routes and laying out roads as a surveyor. We found, as all will find, Mr. Applegate a very intelligent, hospitable, and somewhat eccentric gentleman, situated in a romantic place at the foot of Yoncalla Mountain, upon a large farm, well cultivated, with a good variety of bearing fruit trees, good buildings, outhouses, &c., which give his place the appearance of an old homestead. We spent the day with Mr. Applegate, and at his invitation ascended to the summit of Yoncalla Mountain, where we had a distinct view of the Umpqua and the Willamette valleys, as well as the whole surrounding country. The Umpqua Valley is a succession of hills and valleys with a great variety of scattering timber of different kinds, but mostly of oak. The whole valley is considered the finest grazing country west of the Rocky Mountains, besides being well adapted for agricultural purposes. From Yoncalla we followed down Elk River to its junction with the Umpqua at Elkton, where we struck the main traveled road leading from Scottsburg to Jacksonville. The route from Yoncalla to Elkton is mountainous and rugged, being simply a bridle path or trail most of the way. Elkton is the county seat of Umpqua County, recently located there by the legislative assembly. It is immediately at the junction of Elk River with the Umpqua, and surrounded by high, rolling prairies, thickly covered with grass and vegetation. From Elkton we took the road to Scottsburg. This is the best road of the same length we have seen in Oregon, and is creditable to those who contributed their means and labor in building it. This road, which was built by the inhabitants of Umpqua, intersects the military road about three miles above Scottsburg. Scottsburg is situated at the head of tidewater on the Umpqua, and at the highest possible point of navigation for any sort of watercraft. At this point the river becomes suddenly shallow and rapid, with occasional falls of several feet in a few rods. Unfortunately, at Scottsburg rival interests have brought into existence two towns, upper and lower Scottsburg, They are about two miles apart, both on the same side of the river, and both suffering in consequence of local jealousies and rival interests, which are entirely too common in Oregon. At this time upper Scottsburg appears to be doing the most business; yet it appeared to us the lower town would in the end have a decided advantage, from the fact that vessels can come there and no further without being favored by the tides. Mr. Allan, of the firm of Allan, McKinlay & Co., kindly proffered us a trip to the mouth of the Umpqua River, which is some twenty-five miles distant; we gladly accepted the liberality and kindness of Mr. Allan, and at an early hour we left, in company with several other gentlemen, on the steamer Washington. From Scottsburg, the Umpqua passes most of the way through a canyon of almost perpendicular rocks on either side of many hundred feet high. The scenery is grand and sublime--the river much larger than we expected to find it. There is but one obstruction, called Brandy Bar, to prevent any vessel engaged in the coast trade from ascending the Umpqua to Scottsburg at any stage of water--at high tide vessels drawing twelve feet pass over it. Umpqua City and Gardiner are situated near the mouth of the river. The custom house is located at Gardiner, some four or five miles from the ocean. We found A. C. Gibbs, Esq. the collector of the port, absent, but Mrs. Gibbs extended to us a cordial welcome, and provided a good dinner, which was relished by the whole party, whose appetites had become sharpened by the bracing sea breeze which we encountered below. After convincing Mrs. Gibbs that her dinner was duly appreciated we left upon our upward trip. On our way up we discovered a huge blacktailed deer deliberately walking down to the water's edge, when after drinking for a minute or so, plunged into the river and commenced swimming towards the other side. The captain of the Washington concluded to give chase with the steamer, and therefore put the helm hard up and headed his deership off the shore; after several tacks we finally succeeded in throwing a lasso over the horns of the deer, and bringing him up aside the steamer. It was then decided to bind the captive and take him to Scottsburg alive, which was finally accomplished after considerable difficulty. This is the first time, so far as we know, that a large, full-grown buck, in full strength, has been captured, bound and taken home alive and uninjured by even the Nimrods of Umpqua, who are celebrated as good deer hunters, At all events, it is the first time we ever hunted deer with success on a steamboat. The event created considerable excitement and much merriment to all on board. From Scottsburg we again visited Elkton, and from thence proceeded to Oakland. We noticed on the way one of the best arranged school houses we have seen in Oregon. It is built after the modern style of New England school houses--is well finished, painted and enclosed, and is a creditable monument to the intelligence of the people of the district. We advise other districts to go and do likewise. At Oakland there is a store and a post office, and a good farming country surrounding it. We visited Umpqua Academy, situated on the route from Oakland to Winchester. This academy was built under the supervision and by the efforts of Rev. J. H. Wilbur, who has done much to facilitate and provide the means of education in Oregon. We spent the night under Mr. Wilbur's hospitable roof, and received from him that kindness which he is accustomed to extend to all weary travelers who are without food or shelter. The academy is a fine large building, handsomely finished and pleasantly located in the midst of a beautiful grove, and bids fair to become one of the principal schools on this coast in a short time. Winchester is situated on the north side of the north fork of Umpqua River; there are several stores and machine shops, with mills nearby, where the inhabitants get their supplies. Deer Creek [Roseburg], a few miles further south, the county seat of Douglas County, is a place of considerable business, and is a pleasant location to live for those who admire the beauties of nature and enjoy a quiet life. The country from Deer Creek to the Canyon is one of singular beauty and possesses a rich soil, as was evidenced by the growing crops. This celebrated and never-to-be-forgotten "Canyon" (by those who have passed through it) we shall not attempt to describe, except to say that "the road" is the worst specimen of that name we have ever traveled over, and trust we may never see its like again. A portion of it is emphatically a canyon--a portion a mountain of unusual steepness, and the rest an unfathomable mud-hole, infinitely worse than the "slough of despond" as described by Bunyan. Portions of broken wagons, broken ox yokes and fragments of destruction to property are scattered along the way, from one end to the other, called 10½ miles in length--but which is a hard day's journey to get through it. Once through this canyon, the traveler will find himself in the valley of Cow Creek, which has a narrow interval of good tillable land for some distance where the road crosses and leaves it. We stopped at Mr. Turner's, who keeps an excellent house some eight miles from the south end of the canyon. From this to Jacksonville the road is comparatively good, except "Grave Creek Hills," and with here and there an occasional mud-hole for a short distance. We found good public houses at Grave Creek, also an excellent stopping place at J. B. Wagoner's, about thirty miles north of Jacksonville, also at the crossing of Rogue River. We found Rogue River Valley much more extensive than we had anticipated. It appeared to the eye to be thirty or forty miles long, and from twelve to fifteen broad, which is entirely occupied by settlers. There are a large number of well-cultivated farms, scattered over this whole valley. Jacksonville is situated on the south side, about midway of the valley, and is a place of considerable trade and business. It appears, like all mining towns, to have grown up suddenly. There are, however, a number of good buildings now going up. We noticed one brick store completed, and preparations making for the erection of others. The scarcity of water has stopped all mining operations or nearly so in the immediate vicinity. We visited Ashland Mills, some twenty miles further south, also Butte Creek, some twelve or fifteen miles east [north] of Jacksonville, both of which are pleasant locations. From Jacksonville we proceeded to Althouse, Canyon Creek, Sailors Diggings and back via Sterling. The whole route passes over a rough and mountainous country, with an occasional narrow valley along the small streams, on which settlers have located claims. Many of them present the evidence of good soil and a high state of cultivation. Upon all these streams there is gold to be found in greater or less quantities. We were told by all that miners could make from three to five dollars per day upon almost any of them. We found the miners doing well at Althouse and at Sailors Diggings, where they have sufficient water. At Sterling there is said to be the richest mines yet discovered in Southern Oregon, but the great scarcity of water has seriously checked all mining operations during the spring. The traveler will find an excellent stopping place at Thompson's, on Applegate, and at H. M. Hart's, at Sailors Diggings. We found our old friend J. W. Briggs the occupant of a fine farm in Illinois Valley, surrounded by many of the comforts of life. We were informed that there are several excellent claims yet untaken in Illinois Valley, as well as on Butte Creek and many of the small valleys extending far up into the mountains from Rogue, Applegate and Illinois rivers, &c. Jackson County, although very mountainous and rugged, will doubtless soon become one of the wealthiest counties in Oregon. She possesses considerable good tillable soil and a large quantity of excellent grazing country, in addition to her inexhaustible gold mines. We were accompanied through Southern Oregon by several gentlemen of opposite political creeds and sentiments, among whom were A. C. Gibbs, R. E. Stratton, S. F. Chadwick, Esqrs., and Dr. Drew, of Umpqua, Capt. Martin, of Douglas, Capt. Miller, L. F. Mosher, Esq., of Jackson, and others, all of whom we take pleasure in saying (with a single exception) we found honorable, fair, high-minded gentlemen, notwithstanding the scurrility and falsehoods which have appeared, and will continue to appear, in the Oregon Statesman in relation to this canvass. We also received from the masses of Democrats as well as Whigs throughout Southern Oregon, those civilities which make a man a gentleman, and which the editor of the Oregon Statesman and his echoes have never learned or cannot appreciate. Oregonian, Portland, June 23, 1855, page 2 Attributed to T. J. Dryer in the Oregonian of July 30, 1950, page 73 Roseburg,

Douglas Co.

Dear BrothersO.T. Sept. 23rd 1855 I have an opportunity of writing you a line & take pleasure in saying that I am well. I recd. a letter from Jarvis, the date of which I do not remember, but it contained a large cut of the improved iron grass cutter & it affords me real satisfaction to learn that you prosper so well and also that Mother continues so well. Business in this country is extremely dull, the mines have literally gone in, although we have had & are now having a great excitement about the discovery of gold on the waters of the Columbia, some 600 [sic] miles to the northeast from Oregon City. One family in the next house, about 60 years old, start for there bag & baggage tomorrow. Many are going daily, & many returning cursing the diggings as they come. All agree that gold can be found in all the streams, & equally as good on the sides of all the hills & mountains. The most reliable reports are that men make with pans & rockers from $1 to $3 per day. The same diggings will pay by the improved mode of washing with sluices about three times as much & I doubt not that good-paying diggings will be found in that region next season. I had some thought of going there, but the season has advanced so far & the distance is so great & the snow falls so heavily during winter (in lieu of the rain here in the valleys) that I shall not go this fall & not in the spring, unless the prospects are very flattering. I see by papers from the States that gold mines have been discovered on the Red River near the borders of Arkansas, also from the Salt Lake Mormon settlement that mines have been found on Sweetwater River, & from accounts numbers were leaving Salt Lake for the place. I have also seen men who found gold in the Black Hills a little above Laramie & in the Wind River Mountains. Within two years we shall hear of the discovery of mines that will prove more extensive than any yet known, or at least such is my opinion. A party recently left here on a prospecting trip up this, Umpqua River. One man returned in two days from above the settlements & reports $4 diggings [diggings that yield $4 a day]; the others continued up the river and if not interrupted by Indians may find good diggings. The latter part of this, or the first part of next week, I am going with a party up the south branch of the Umpqua River in search of diggings. Some men that have seen the country have strong hopes of it. If I should find diggings that will pay on either branch of this river I think I had better remain here during the winter and meet Jarvis in San Francisco in the spring, but of this I will write you more hereafter. The rights for Oregon & Washington territories for the reaper had better be sold for what they will bring, more or less. Times are so hard & money so scarce that men worth large amounts of property find it difficult to do business & pay taxes; hence I think you would hardly be justified either in building here or bringing any large number of machines to sell unless you chose to sell on a credit. In California people have more money to do business with. California supplies herself now & Oregon sells her but little. The wheat crop was ruined by smut & grasshoppers, & what there is cannot be sold for want of purchasers. It has no price. Cattle are the only thing that will sell, & yet a few years longer will reduce the price of stock till it will be hardly worth raising, unless mines shall be discovered or some unlooked-for impulse shall be given to business here. I consider Oregon about done over. People here have been importing almost everything they use, while they expect nothing but money. Their money is exhausted; they are without manufactures of any kind, have for the last 2 years only had something to sell & there are no purchasers. So you can readily comprehend our situation. I have money due me here & cannot collect enough to take me to the States & back. . . . John C. Danford, letter probably written to his brother Ebenezer Danford (manufacturer of a mower and reaper) in Chicago. "Letters of John C. Danford, Oregon Territory 1847-1856," transcribed by Frank Richard Sondeen June 1961. Fremont Area District Library, Fremont, Michigan. WILD LIFE IN OREGON.

Early

in October, 1855, with an old companion of my

peregrinations--one of those golden-tempered, delightful traveling

companions with whom to associate is a perpetual treat--I found myself

on board the staunch steamship Columbia,