|

|

The

World's Going to Hell And has been for a long time.

Articles about "the good old days" and the current rotten generation:

The Young Man of the Age.

Not long since

we saw a tear gathering in the eye of an old man, as he spoke of the

past and the present--of the time when he burned pine knots upon the

rude home hearth for light to obtain a scanty education, and then

compared the ten thousand privileges which are now scattered

broadcast around every door. O, said he in tremulous tones, the young

men of this day do not appreciate the light of the age they live in.

The words of the old man made us sad, while at the same time we felt

mortified that so many of our young men fail to improve the advantages

within their reach--They are even continually muttering about their

lot, and pushing for positions where they can win the reward without

the sweetening, purifying, ennobling sacrifice of toil. The mist-cloud

enjoyments of a day are eagerly sought after, to the exclusion or

neglect of the more honorable, intellectual and useful. In truth, few

of our young men know anything of the value of the privileges around

them.

Oregon Weekly Times, Portland, July 31, 1852, page 1 Modern Improvements.

Oregon Spectator, Oregon City, April 28, 1854, page 1

"Modern improvements"? I wonder where they are. Perhaps it is the

fashionable cloaks that take leave of their shivering owners at the

hips; or the long skirts, whose muddy trains every passing pedestrian

pins to the sidewalk; or the Lilliputian bonnets, that never a string

in shopdom can keep within hailing distance of the head; or the flowing

sleeves, through which the winter wind plays around the armpits; or the

breakneck high-heeled boots, which some little, dumpy feminine has

introduced to gratify her rising ambition, and render her tall sisters

hideous; or the gas-lit-furnace-heated houses, in which the owners'

eyes are extinguished, and their skins dried to a parchment; or,

perhaps, it is the churches, of such cathedral dimness that the

clergymen must have candles at noonday, and where the congregation are

forbidden to express their devotion by singing, and forced to listen to

the trills and quavers of some scientific stage mountebank; or perhaps

'tis the brazen irreverence with which Young America

jostles aside gray-headed Wisdom; perhaps the comfortless, forsaken

fireside of the "strong-minded women"; perhaps 'tis the manly gossip,

whose repetition of some baseless rumor dims the bright eyes of

defenseless innocence with tears of anguish; perhaps 'tis the schools

where a superficial show of brilliancy on exhibition days is considered

the ne plus ultra of

teaching; perhaps 'tis the time-serving clergyman, whose tongue is

fettered by a moneyed clique; perhaps 'tis the lawyers who lie--under a

mistake! perhaps 'tis a doctor, whom I saw yesterday at Aunt Jerusha's

sick room, a little thing, with bits of feet, and mincing voice, and

lily-white hands and perfumed mustache. I wanted to inquire what ailed

Jerusha, so I waited to see him. I wanted to ask him how long it would

take him to cure her, and if he preferred pills to powders, blisters to

plasters, oatmeal to barley gruel, wine whey to posset, arrowroot to

farina, and a few such little things, you know. He stared at me over

his dickey, as if I had been an unevangelized kangaroo, then he sidled

up to Jerusha, pried open her mouth and said "humph"--in Latin. Then he

crossed his legs, and rolled up the whites of his eyes at the wall, as

if he expected some Esculapian handwriting on the wall to enlighten him

as to the seat of Aunt Jerusha's complaint. Then he drew from his

pocket a box with a whole army of tiny bottles, and uncorking two of

them he nipped out a little white speck from each, which he dissolved

in four quarts of water, and told Jerusha "to take a drop of the water

once in eight hours." Tom Thumb and Lilliput! He might as well have

tried to salt the Atlantic Ocean with a widow's tear! He should be laid

gently on a lily leaf, and consigned to the first stray zephyr.

Ah, you should have seen our good, old-fashioned Dr. Jalap; with a fist like a sledgehammer, a tramp like a war horse, and a laugh that would puzzle an echo. He was not penurious of his physic; he didn't care a pin how much he put down your throat--no, nor the apothecary either. He pilled and potioned and emeticked and blistered and plastered till you were so transparent that even John Mitchell (and he's the shortest-sighted being living) could have seen through you. And then he braced you up with iron and quinine till your muscles were like whip cords, and your hair in a bristle of kinks. He was human-like, too; he didn't stalk in as if Napoleon and the Duke of Wellington were boiled down to make his grandfather. No, sir; he'd just as lief sit down on a butter firkin as on a velvet lounge. He'd pick up Aunt Esther's knitting needles, and talk to Grandpa about Bunker Hill, and those teetotally discomfrizzled, bragging British, and offer Grandma a pinch of snuff, and trot the baby, and stroke the cat, and go to the closet and eat up the pickles and doughnuts, and make himself useful generally. He didn't have to stupefy his patients with ether so that they needn't find out how clumsily he operated. No, it was quite beautiful to see him take a man's head between his knees, and drag his double teeth out. He didn't write a prescription for molasses and water, in High Dutch; he didn't tell you that you were booked for the River Styx, and he was the only M.D. in creation who could annihilate the ferryman waiting to row you over. He didn't drive through the town with his horse and gig at breakneck speed, just as meeting was out, as if life and death were hanging on his profitless chariot wheels. He didn't stick up over his door "at home between 9 and 2," as if those consecrated hours were all he could bestow upon a clamorous public, when he was angling in vain for a patient every hour in the twenty-four; nor did he give little boys shillings to rush into church, and call him out in the middle of the service. No, Dr. Jalap was not a "modern improvement." AN OLD MAN'S COMMENT ON MANNERS.--Not long since, as I was riding through one of the adjoining towns, I met a group of boys and girls returning from school. Their merry laugh and play was somewhat checked at the approach of my carriage, and the grey head in it. They ranged themselves alongside of the traveled path, and as I passed, each boy took off his hat and joined the girls in what, in my young days, we called "making their manners" to me. This phrase is obsolete now; it means that the girls curtsied and the boys bowed. It is a long time since I met with such attention. Passing along our streets in the city, the young misses twirl their umbrellas in my face, the boys drive their hoops against my tottering limbs, and set up a loud laugh when it knocks away the old man's cane. Young gentlemen, as they are now called, I believe (they used to be called boys at that age), four feet high and less, puff their cigars in my face, and spurt their tobacco juice on my clothes; and young misses, ladies I should say, of about the same height, make wry faces at the grey heads who do not give them the better part of the sidewalk. You see, Mr. Editor, I cannot for the life of me call things by their present names. I have outlived the language that Parson Wilson, Deacon Dexter and Mr. Taft taught in the public schools, but I do want to know whether the conduct of those country boys and girls does not savor of "old fogeyism," and whether that of our city young gentlemen and ladies is not "progress." If you don't know, will you ask the superintendent, or the mayor, or the professor of didactics, I believe they call him. Oregon Spectator, Oregon City, November 11, 1854, page 2

The Rising Generation in this City.

Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, March 28, 1868, page 1 The following from the San Francisco Times expresses our views, and it contains many hints that are applicable to this locality:

No one can walk our streets, or read the local columns of our dailies, without coming to the conclusion that, taken as a class, the children of San Francisco are far from being trained in the way they should go. It is not only the poor waifs of society--the children with no one to care for them, or whose parents are ignorant, dissolute, and degraded--who display a fearful precocity in all that is bad, but it is in many cases the children of respectable, intelligent, well-to-do people. There is evidently something wrong. We do not think that any fault can be found with the standard of intellectual education, but we fear the standard of moral education is far too low. Our schools are good enough; the evil is in the discipline of the family. Most parents are far too careless as to what company their boys and girls keep, and how they spend their leisure time. They send their children to school, spare no cost to give them a "good education," but take no pains to give them good habits and instill into their minds those fundamental ideas of duty, without which knowledge is of no avail. In their government of their families, they are guided by no fixed rules. They tolerate disobedience, impudence and waywardness because it is too much trouble to restrain or punish, until their influence is entirely gone, and the child is abandoned to its own impulses before good habits are formed and its judgment is sufficiently matured to enable it to choose right. That fearful thing--a completely spoiled child--which means a child which is a torment to itself and all about it, and a disgrace to its parents--is no rarity in this city, and the legitimate results may be seen in the records of our police courts, industrial schools, Magdalene asylums and prisons. In a well-timed article on this subject, suggested by the arrests of children of tender age, the Bulletin of last evening makes the following sensible remarks: Whether corporal discipline be exercised in both the school and family, or whether it be exercised in the family alone, it ought certainly to be exercised to the fullest extent which is safe, before having resource to the police, the magistrate, and the penal regime of a public reformatory. The evil begins with infancy. The children of some parents never learn obedience when young, and therefore are difficult of control when six and eight years of age. The cruelest of all wrongs to children is to leave them to grow up like weeds, and it would be well if the law could punish the father who neglects to train his children in good habits, as it does the man who neglects to supply them with food. Moral ruin is as great a crime against the child as physical ruin by starvation, and the law might as well take cognizance of one as the other. Willfully to rear children to vice and crime is more injurious to the well being of the community than the willful maiming of individuals, and if the law punishes the latter offense, it should punish the former. The child suffers at the time by being given up to bad passions, and never knows what an innocent and happy infancy is; the boy suffers afterward, because even humanity has to use cruel measures in the hope of reforming him, and then too often fails. Society has criminals where it should have good members. In every case of vicious and disorderly habits being proved against a child under fourteen years of age, the parent or guardian is morally though not legally answerable, whenever criminal negligence is the cause. Society has, for years, tended toward leniency and mild measures; but it is doubtful whether the acknowledged evils of Puritan severity, great as they were, ever were so mischievous as modern laxity and indulgence. We do not believe in cruelty to children; but we do not think it safe to entirely reverse the maxim of Solomon. A wise parent need never resort to undue severity; but will always exact obedience, and will feel the responsibility devolving upon one who has, to a great extent, the charge of shaping the destiny of an immortal soul. THE great danger of this country, just now, says the Marysville Appeal, is not the Chinese immigrants, but American laziness. No American wants to do any hard work any longer; he imposes it on machinery or foreigners. He won't serve an apprenticeship to any manual art, or dig, delve, or mine, or plow, if he can get anybody else to do it for him. There are 5,000,000 blacks at the South, and 10,000,000 whites, and the whites do comparatively nothing, nevertheless, but howl for "more labor," being themselves nearly to a man idle. The farm houses at the North are full of well-dressed young ladies waiting to be married, and the father is left to till the farm owing to the departure of the boys to peddle illustrated books, quack medicines, and patent rights, or to be clerks in a store. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, December 18, 1869, page 2 What Is Our Progress?

Our modern progress is merely a change. We invent machinery to spare

muscular labor. Great is our shout of praise when a new sewing machine,

for instance, comes in. The croakers who hint that, after all, it may

not be such a boon to the weary operative, are laughed to scorn. BY AN OLD FOGEY. Well, we have been running machinery at a top speed this half century, and now the apostles of progress are again crying out. The sewing machine, in two years, destroys the spine of our women and renders them sterile. The working men are burning down houses in riot (as at Chicago), demanding the reduction of labor to eight hours a day. Medical authorities concur that the lack of healthy exercise, combined with the cramped condition of people who work on machinery, is rooting out and absolutely destroying the lives of laborers in civic hives. Ministers of the gospel and the moral censors of the press agree that our large manufacturing centers are the hotbeds of crime and misery. What in the world are we going to do, then? We can't be old fogeys and acknowledge that our fathers understood some things better than we. We can't tear down the machinery, and employ and give happiness to three times as many men. That would be too medieval to be thought of. We must go on, like in tight corsets, to consumption and early extinction of the race; permitting our places to be filled by foreigners who come from those slow countries beyond the Great Sea. It really seems as if the spirit of evil takes especial delight in marring every step of our modern progress. If we travel faster, we get smashed up, and sent, unprepared, to kingdom come. If facilities of emigration are afforded to this generation beyond all preceding, countless souls are lost or driven to shame by the transition. The intellect of man sharpens and the body decays. The beardless youth of today knows more than his grandsire of yesterday. We have brought the hills of the moon within fifty miles of us; but faith in the Son of the Omnipotent God, who died for the world, is dying away. With every good we progress towards evil. The bright coin is ever dimmed with the filthy alloy. By pride and avarice, the evil spirit seizes hold of every successive scheme of modern progress. If wages advance, another story goes up on the house of the laborer. Silks supplant cotton; two hours more are added to the domestic slave. Old-fashioned solid erudition vanishes, and trashy sentimentalism usurps its place. Men are made beasts of burden to support shams. The newly discovered machinery only adds to the demands of luxury. By great ingenuity, the archenemy of man so orders things that we have sensation preachers even, and the loudest declaimers against shams are the greatest shams themselves. No one wishes to labor, either, as an old fogey. The very sewing girls go to their homes at seven, with books in their hands that they may be mistaken for wealthy misses. The devil inspires the heart of the employer with avarice, and then he tunes the wheel of progress to the doleful key that suits the strain of human misery; so he (the villain!) stirs the heart of the household of the poor man to luxury and vain display, till the stooping shoulders and whitening hair of that poor man mark the premature approach of darkness. The remedy for all this is to abolish the worship of appearances--vain shadows. Esse potius quam videri. Be, rather than seem to be. Democratic News, Jacksonville, September 10, 1870, page 1 Grandpa's Soliloquy.

It

wasn't so when I was young,

We used plain language then, We didn't speak of "them galoots," When meaning boys or men. When speaking of a nice hand write Of Joe, or Tom, or Bill, We did so plain--we didn't say "He swings a nasty quill!" And when we seen a gal we liked, Who never failed to please, We called her pretty, neat and good, But not "about the cheese." Well, when we met a good old friend We hadn't lately seen, We greeted him--but didn't say, "Hello, you old sardine." The boys get mad sometimes, and fit, We spoke of licks and blows; But now they whack him on the snoot, And "paste him on the nose." Once, when a youth was turned away From her he loved most dear, He walked off on his feet--but now He "crawls off on his ear." We used to dance when I was young, And used to call it so; But now they don't--they only "sling The light fantastic toe." Of death we spoke in language plain, That no one will perplex, But in these days one doesn't die-- He "passes in his checks." We praised the man of common sense, His judgment's good we said; But now they say, "Well, that old plum Has got a level head." It's rather sad the children now Are learning all such talk; They've learned to "chin" instead of chat, And "waltz" instead of walk. To little Harry, yesterday-- My grandchild, aged two-- I said, "You love your grandpa?" Said he "You bet your boots I do." The children bowed to strangers once, It is no longer so; The little girls as well as boys, Now greet you with "Hello." O, give me back the good old days, When both old and young Conversed in plain, old-fashioned words, And slang was never "slung." Iowa South West, Bedford,

Iowa, January 16, 1875, page 2

OLD TIMES.What Our Forefathers Did for a Living.

Half a century ago bellows-making was a thriving trade. Every house had

its pair of bellows, and in every well-furnished mansion there was a

hung a pair by the side of every fireplace. Ipswich, in Massachusetts,

acquired quite a notoriety all over New England for the elegant and

substantial articles of the kind it produced. But as stoves and grates

took the place of open-air fireplaces, and as coal was substituted for

wood, the demand for bellows diminished until the business as a

separate trade quite died out. The same is true of flint cutting.

Flints were once necessary, not only for firearms, but for tinderboxes,

and a tinderbox was as necessary for every house as a gridiron or a

skillet. Everyone who looks to childhood of forty-odd years ago must

remember the cold winter mornings, when the persistent crack of the

flint against the hard steel sent up from the kitchen an odor of

igniting tinder and sulfur, which pervaded the house. I have no more

idea of what became of the flint producers than the old man of

sorrowful memories who, three or four times a week, called at our door

with brimstone matches, for sale at one cent the half-dozen bunches.

Both have been as completely banished from England and New England as

have the red Indians and the Druids. Then, again, are gone the

pin-makers, who, though they have been in their graves this quarter of

a century, still figure in lectures and essays to illustrate the

advantages of division of labor. Instead of a pin taking a dozen men to

cut, grind, point, head, polish and whatnot, as it used to do, pins are

now made by neat little machines at the rate of three hundred a minute,

of which machines a little child attends to half a dozen. Nail-making

at the forge is another lost industry. Time was, and that in this

nineteenth century, when every nail was made on the anvil. Now, from

one hundred to one thousand nails per minute are made by machines. The

nailer who works at the forge has a small chance in competing with such

antagonists, and he would have no chance at all were it not that his

nails are tenfold tougher than the others. As it is, the poor men

follow the all but hopeless vocation, and are compelled to live in

handgrips with poverty. In the days of Presidents Madison and Monroe,

and even later, straw bonnet making was practiced in every middle-class

house where there were growing families, and straw plaiting formed the

staple of domestic leisure work. At my grandfather's, around the huge

kitchen fireplace, Caesar, born a slave, who sat on an oak bench,

directly under the gaping chimney, and we boys, who crowded upon the

settee, used to pass winter evenings splitting straw, while the lassies

were plaiting them. Then bonnets were bonnets, covering the head with a

margin of a foot or two to spare, and presenting a sort of conical,

shell-shaped recess, in which dimpling smiles and witching curls

nestled in comfort. The work has vanished, and will never reappear,

unless the whirligig of fashion should glide again into the forsaken

track.

Corvallis Gazette, March 16, 1877, page 4 How People Lived Fifty Years Ago and How They Live Now. [C. C. Coffin in May Atlantic.]

A

half century ago a large part of the people of the United States lived

in houses unpainted, unplastered and utterly devoid of adornment. A

well-fed fire in the yawning chasm of a huge chimney gave partial

warmth to a single room, and it was a common remark that the inmates

were roasting one side while freezing the other; in contrast, a

majority of the people of the older states now live in houses that are

clapboarded, painted, blinded and comfortably warmed. Then the

household furniture consisted of a few plain chairs, a plain table, a

bedstead made by the village carpenter. Carpets there were none. Today

few are the homes, in city or country, that do not contain a carpet of

some sort, while the average laborer by a week's work may earn enough

to enable him to repose at night upon a spring bed.

Fifty years ago the kitchen "dressers" were set forth with a shining row of pewter plates. The farmer ate with a buck handle knife and an iron or pewter spoon, but the advancing civilization has sent the plates and spoons to the melting pot, while the knives and forks have given place to nickel- or silver-plated cutlery. In those days the utensils for cooking were a dinner pot, teakettle, skillet, Dutch oven and frying pan; today there is no end of kitchen furniture. The people of 1830 sat in the evening in the glowing light of a pitch knot fire or read their weekly newspapers by the flickering light of a "tallow dip"; now, in city or village their apartments are bright with the flame of a gas jet or the softer radiance of kerosene. Then, if the fire went out upon the hearth, it was kindled by a coal from a neighboring hearth, or by flint, steel and tinder. Those who indulged in pipes and cigars could light them only by some hearthstone; today we light fires and pipes by the dormant fireworks in the match safe at the cost of one-hundredth of a cent. In those days we guessed the hour of noon, or ascertained it by the creeping of the sunlight up to the "noon mark" drawn upon the floor; only the well-to-do could afford a clock. Today, who does not carry a watch? and as for clocks, you may purchase them at wholesale, by the cartload, at sixty-two cents apiece. Fifty years ago how many dwellings were adorned with pictures? How many are there now that do not display a print, engraving, chromo or lithograph? How many pianos or parlor organs were there then? Reed organs were not invented till 1840, and now they are in every village. Some who may read this article will remember that the Bible, the almanac and the few textbooks used in school were almost the only volumes of the household. The dictionary was a volume four inches square and an inch and a half in thickness. In some of the country villages a few public-spirited men had gathered libraries containing from three to five hundred volumes, in contrast [to] the public libraries of the present, containing more than ten thousand volumes, [which] have an aggregate of 10,650,000 volumes, not including the Sunday school and private libraries of the country. It is estimated that altogether the number of volumes accessible to the public is not less than 20,000,000. Of Webster's and Worcester's dictionaries, it may be said that enough have been published to supply one to every one hundred inhabitants of the United States. Ashland Tidings, May 30, 1879, page 1 The oration of Francis Fitch, Esq., on the Fourth at Medford was one of the best examples of that style of oratory that has ever been delivered in southern Oregon. Disdaining to soar to the heights of fanciful imagery, the speaker confined his effort to a review of existing conditions and the probable resultant effects within the next generation of the present tendency to extravagance and corruption in the management of public affairs, and the unlicensed encroachments of wealth and the corporations. "Local Notes," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, July 18, 1890, page 3 Insomnia is fearfully on the increase. The rush and excitement of modern life so tax the nervous system that multitudes of people are deprived of good and sufficient sleep, with ruinous consequences to the nerves. Remember, Ayer's Sarsaparilla makes the weak strong. Medford Mail, May 11, 1894, page 3 Mail Office Devil:--"Say, the boys and girls last week had lots of fun with their homemade sleds, didn't they? No store sleds here--snow is too seldom. Reminded me of the time when I was a lad. I had to either make my own sled or slide downhill in a sap trough. In those days there were no bicycles, no tricycles, no red express wagons, no store sleds, no air guns, none of the many things which the boy of today thinks is absolutely necessary to his happiness. But, somehow, with a sap trough sled, cart with wheels sawed from the end of a log, and my old muzzle-loading rifle with a broken lock and a buckskin string to pull the hammer back with, a rifle with which I could knock a squirrel's eye nine times out of an impossible ten, I kind o' believe I had about as good a time as do the boys of today." "Echoes from the Street," Medford Mail, February 4, 1898, page 7 Fifty years ago oratory was the great and winning gift whereby to obtain high station. Webster, Clay, Calhoun, Corwin and others gained their eminence and retained their hold upon the people largely through their oratorical ability. Even as late as Lincoln's day no other capacity was equal to the gift of extraordinarily excellent speech, without which he would never have been president, or risen to eminence. Debating societies flourished in every backwoods school district, and the boy who could talk most fluently was the one pointed out as the inheritor of political honors. In Congress the best speaker was the real leader, and the only great senators were those who could make great speeches. All this is changed, and the orator is generally a bore. The silent man, who plots and logrolls and bargains and counts noses, is the power in legislation. The greatest of speeches in Congress scarcely ever changes a vote on an important measure, and the votes turned by the best campaign orators are few and far between. The practical politician has superseded the orator. In this change the newspaper has played an important part. Voters read the news, and are about as well informed on public questions as the campaign orators or average congressman. It is an era of writing and reading, rather than of talking and listening. Medford Mail, July 5, 1901, page 2 The growing tendency to look upon marriage as a temporary bond which can be thrown off or assumed at will is the logical result of loose divorce laws and the increasing tendency to imitate the customs of the fast sets abroad. It is high time for persons of all classes to protest against the general laxity of morals that is seen to exist in present-day society. Public sentiment is on the right side, and it is important that the old traditions which once guarded the American home should be revived. Medford Mail, November 29, 1901, page 2 A Farmer Pessimist.

From Tuesday's Oregonian.An old farmer, who had a fine ranch in the foothills of the Cascades, and who had been reading in the papers about forestry reserves and forestry laws and reforesting whole regions, was talking these matters over with a government official yesterday. He said the idea made him weary, and he was glad that he had not much longer to stay in this weary world. He said that he had done many years of hard work, and put in his best licks clearing away the forest to make farms. He helped to clear a farm in New England in his boyhood, afterward another one in New York State, later he had, with the help of his boys, cleared another in Missouri, and then he came to Oregon and had been here ever since getting another cleared, and he was done. He should clear no more land, and it would make no difference to him if the whole country were reforested. He had come to the conclusion that nearly everything in the world would be exterminated or exhausted within a few generations. He had seen the herds of wild buffalo shaking the earth with their gallop, but they were all gone. The wild Indians who had made life a burden to him on several occasions were all disappearing. The wild game and fur-bearing animals were gone or going. The fish in the sea were being exhausted, the whales practically exterminated. The sturgeon of the Columbia had been all caught out, and it was only a question of a few years when the salmon would be all gone, despite artificial propagation, and everything was in the same boat. The timber of the United States would all be cut off in a short time. The coal would be exhausted, and the iron, the gold, silver and copper would be all dug out and used up, the oil wells would be exhausted and there would be nothing to cook with, nor much of anything to cook, and he wasn't feeling very well himself, anyhow. He could not do as much work in a day as he used to, and he could not eat to much, nor walk so far, nor jump so high, and his seeing and hearing were failing and nothing tasted as good as it used to. The old man's friend tried to cheer him up but found he had taken a bigger contract than he had figured on, and asked to be excused on account of a business appointment. So the old man strolled off, remarking, "When I come into town again I will come in and talk the situation over with you," a thing which his friend says he will take particular pains to see that the old man doesn't get a chance to do. Medford Mail, March 14, 1902, page 6 High-Pressure Days.

Men

and women alike have to work incessantly with brain and hand to hold

their own nowadays. Never were the demands of business, the wants of

the family, the requirements of society, more numerous. The first

effect of the praiseworthy effort to keep up with all these things is

commonly seen in a weakened or debilitated condition of the nervous

system which results in dyspepsia, defective nutrition of both body and

mind, and in extreme cases in complete nervous prostration. It is

clearly seen that what is needed is what will sustain the system, give

vigor and tone to the nerves, and keep the digestive and assimilative

functions healthy and active. From personal knowledge we can recommend

Hood's Sarsaparilla for this purpose. It acts on all the vital organs,

builds up the whole system, and fits men and women for these

high-pressure days.

Democratic Times, Jacksonville, April 10, 1902, page 2 Mr. Vawter's oration was a model, both as to brevity, for he did not talk for the long period that so many Fourth of July speakers do, and the timeliness of the topics discussed, for he did not follow the lines of the average stereotyped celebration oration, but talked of today. Clearly and convincingly Mr. Vawter proved that the pessimist's wail, that public virtue and patriotism were on the decline, was an unwarrantable fear, born of a morbid mind. American political life was growing purer with each year. Conventions were more fair in their deliberations, elections more honestly carried on, and public officials more true to the fealty they owe to the people than at any previous time in the history of the republic. And as to patriotism the events of recent years have shown that the American people are just as patriotic as they were in the days when Paul Revere made his famous ride. He attributed to the American sense of justice and liberty, the cause for the United States attaining the high position it now holds in the world's affairs. The way in which Cuba has been befriended, and the magnanimous treatment accorded to China in that country's late trouble, are without parallel in the history of nations. The marvelous growth of the nation in industrial, commercial and other lines was but another compliment to American brains and energy. Mr. Vawter closed his speech with a masterly defense for the nation's expansion from the time of Jefferson down to today. "Jacksonville's Celebration," Medford Mail, July 11, 1902, page 3 TRIVIAL TYRANNY.

There was a delightful schoolmistress who used thus to imporess on her

scholars certain refined distinctions: "My dears, horses 'sweat,' young

men 'perspire,' young ladies are 'all in a glow.'" In these outspoken

days when a spade is called at very mildest a spade, the gentle euphuism is a matter of amusement, to be laughed at with affectionate patronage, like an old-time gown out of Grandmother's chest.

Young ladies have disappeared and girls get quite as warm as their brothers nowadays, and on the whole the change is vastly for the better, frankness being own sister to truth and mortal foe to affectation. Yet, the further we go from the brocade days, the more inevitably we must recognize a price paid for our freedom, a certain stately charm gone out of life and human intercourse. The formality of those times made barriers, and in barriers, after all, lie the half of romance. It is the face beneath the veil that we are most eager to see, the voice behind the wall that tempts us to most strenuous climbing. What could be prettier or more inaccessible than a young lady all in a glow? Man is still at heart essentially old-fashioned, and the modern girl, rejoicing in her new equipment of frankness and coifrage and unconventionality, sometimes finds him strangely unresponsive. Theoretically he is thoroughly in sympathy with her, as a reasonable being needs must be, but for all that he dimly realizes that something is missing--a price has been paid. The ostentatiously modest scoop bonnet, with its defensive ruffle behind and its lace curtain across the front, gave a piquancy that the unveiled intercourse of today can never attain. Oregon Statesman, Salem, October 1, 1903, page C2 PAST AND PRESENT MANNERS OF BOYS AND GIRLS

Editor Mail Tribune:

A few days ago,while wife and I were basking in the warm autumn

sunshine at our front gate, discussing and admiring the many elegantly

dressed ladies passing in their many varieties of autumn colors and

costumes that would keep the rainbows guessing whether God gave all his

beautiful colorings to the cold, green earth below or the starry

heavens above, and to note the indescribable bevies of clean,

rosy-cheeked school children leisurely passing to and fro, our

attention was particularly attracted to a bright-appearing boy of some

12 summers, perhaps, who came sauntering aimlessly up with but little

concern apparently, smoking the favorite cigarette, and stopped in

front of us, and without introduction or any preliminary remarks, said:

"Hello, Joe and Mary. Did you folks see that old guy of a rainbow of a

man that just passed by with gray hair and beard and carrying a cane?"

Well, kind reader, if a thunderbolt from a Southern Oregon sky could

not have struck us with more force and astonishment than to hear the

words just spoken from the innocent lips of this bright, mischievous

youth, and our feelings were touched with sympathy and pity for the

unlimited neglect of his home training and the lack of a judicious

application of that old-time remedy, hazel and peach tree sprouts. But

sweet memory at once recalled to mind my limited experience in home

training of the boys and girls in the good old pioneer days of 50 years

ago. Briefly told, we were taught what obedience means at home and at

school and that never-to-be-forgotten indelible copy that manners makes

the man, but does the above apply to this fast, busy age of attractive

environments, and the knotty question arises, has there been any

noticeable improvement in the teaching of manners, morals and the

proper respect due to the aged gentleman and lady among the young boys

and girls of the 19th century, which we think is the keynote and

foundation of their future lives. But we leave this for the modern

parent and educator to answer.

Well, we looked our Young America boy acquaintance over pretty carefully and became fully convinced he was not a Medford boy, but one of those no, yes, hello, filthy cigarette, old guy class of boys that had perhaps been smuggled into our clean, virgin city of good manners and morality from some of the old pioneer mossback cities of the north, the home of reform schools and [line of type omitted] and many other fruit and society pests which, we note, are moving rapidly south to taint and infest and corrupt our beautiful indescribable Rogue River Valley of peace, power and plenty. In conclusion, permit your humble writer to suggest to the clean, bright, promising young boys of our young city to be prepared to meet all these vicious habits with the manly words, "No, sir." J. G. MARTIN.

Medford Mail Tribune, November 29, 1909, page 6

DEVIL WAGONS RIGHTLY NAMED.

For

the man who uses shank's mare, the cost of travel has been increased by

the man who rides in his automobile. Such is the conclusion of the

Massachusetts commission on the cost of living, says the New York World. It is a

good deal like saying that the price of cake fixes the price of bread,

but it is true, as common experience proves.So much leather is used nowadays in the manufacture of automobiles that hides are higher, leather is higher and so on down step by step until the price of boots and shoes is raised. It is the same story with rubber. The demand for the crude material in the automobile trade has hoisted prices all along the line, from overshoes to pneumatic tires, and most of all in London, for the shares of new Scotch rubber-plantation companies. The more people ride, the more the man who walks pays for going afoot. The automobile has developed into an expensive luxury for the people who do not use it. It has added to the cost of maintaining the roads in good repair and of going well shod in dry and wet weather. It has created new styles of clothes and new resorts for dear food and drink. At the present rate of consumption lobsters and champagne are likely to go higher. The only thing that has been cheapened is human life. The cost of high living, as James J. Hill said, has made the cost of living higher. The automobile was well named "the devil wagon." Medford Mail Tribune, May 20, 1910, page 4 I also remember that I could have bought most of that property over there for a very little money, and just put part of it up. Now a feller has to interview the cashier of the bank before he can hardly look at that ground with a view to having. Well, us old fellers can't help it. We started when the world traveled like an ox wagon and you could see things easily before you go to them. Now, with airships, automobiles and sich like, you have to set your alarm clock for day after tomorrow in order to get up on time to see things before they get by. "East Main Street Twenty Years Ago," Medford Mail Tribune, June 5, 1910, page 3 The 20th century schools may be up-to-date in many respects but I am of the opinion they are generally sadly deficient in the teaching of articulation. Few young people now-a-days make any attempt to articulate plainly & clearly. It is becoming a lost art. They go on the hop-skip-&-jump in reading aloud or in conversation. But then, this is a fast age anyhow. Diary of W. J. Dean, May 3, 1913 TOO MUCH TIME ON NONESSENTIALS IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS

To the Editor:

I see in yesterday's paper a criticism of the various so-called "supernumerary" textbooks in use in the fifth year of the grammar school. While the writer was a little facetious at times, it seems to me there is much merit in his criticisms. We are told the average school life of a child in Oregon is about six years. Now, if that be true, the fifth year must be the end-all of school life with many. I have observed the work of many pupils of this grade, and I am convinced much, too much, of their time is spent in studying microbes, diseases and their causes, courses and treatments; the philosophy of history and economics. Large encyclopedias are brought into use, and their investigations are made to cover a university range. Also I have observed that reading and spelling are severe tasks for them, and when children are away on vacation their letters home glitter with misspelling of the most common words. When struggling with a difficult problem, it often seemed as difficult for these children to perform the operation as to know what operation to perform. The textbooks forced upon our long-suffering children and their teachers seem to call for culture, culture, culture. The system ignores largely the foundation, while already the beautiful, artistic outside and upper finish is being laid on. Too much veneering before the body structure is built. I rather incline toward the old-fashioned way of teaching reading. Every student read each day. Reading was done with mathematical precision as to pronunciation. There were contests in reading, also much concert reading, and many classic selections were learned by rote and used as basis for further drills and to build up perfect pronunciation with perfect articulation, and for the further purpose of weeding out crudities and mishaps in naming words. Of course, this required time, much time. This left but little time for a fifth grade boy to run down the atomic component parts of a molecule of an organic compound, and but little opportunity to trace out the germs of the Magna Carta in the various ramifications of the history of the Anglo-Saxon world. Neither did it leave many hours each day to acquire the power to force every mouthful of food into its proper classification as nitrogenous, carbonaceous etc. Reading is the great implement by which most knowledge in the schools and ever after is acquired. An able and delicate use of this implement ought to be the heritage of every man or woman, and it must come to such in the early years of school life. There are few good readers in this day and age. If present methods are pursued there will be almost none a generation hence. Good reading seems in course of ultimate extinction. The same may be argued with regard to the teaching and study of arithmetic. To acquire skill in adding and subtracting seems to be relegated to manhood years. A great banker told me that young men must invariably learn anew the fundamental operations of arithmetic on entering the bank as an employee. The teachers have no time for drills. A child gulps down a case of problems and hurries to the next, and so on to the end. Involution and evolution engage his attention while he remains an imbecile of inaccuracy in everyday calculations. No, I am not faulting our teachers. They work like fighting fire to "make the grades." The course of study is packed with big books treating with university subjects, and the law must be upheld that positions may be held. Culture will follow in due course, but true education must begin with a solid mastery of reading, writing, arithmetic and spelling. That is the way Abraham Lincoln began. PATRON.

Medford Mail Tribune, September 9, 1914, page 5In those days everyone worked. My father kept busy all day, splitting rails and building fences, and later plowing the meadow land and broadcasting his wheat by hand. They often harrowed it in by cutting down a small oak grub tree and dragging it over the soil until the clods were broken up and the wheat thoroughly covered. We threshed the wheat by tramping it out with horses, and then they ran it through a hand fanning mill. We used to haul the wheat to the McLoughlin mill at Oregon City. When the water was high they swam the horses and floated the wagon over, or sometimes they would take the wagon to pieces, carry it over on a log across the stream, carry the grain over on their shoulders, and put the wagon together on the other side. Nowadays all you have to do to get a sack of flour is to go to the telephone, but then it was not so simple a matter, even if life was supposed to be more simple in the early days. Malvina Millican Hembree, Mrs. James Hembree, quoted by Fred Lockley, "Oregon: In Earlier Days," Oregon Journal, Portland, November 14, 1914, page 4 When I was a grown girl, along about 17, I met, and married Asa Peterson when I was nearly 19, and my little boy was pretty nigh a year old when we started for Oregon. The whole prairie was bright and the air was sweet with the smell of wildflowers when we started across the plains in the spring of '45. We didn't have much to move. We hadn't been married long. Nowadays a girl won't marry her man unless he has a good job and a home and money in the bank, but it don't appear that they get along any better than we did 70 years ago. We were willing to start at the bottom of the ladder and climb up together. When I got married I started housekeeping with a 2-year-old colt, a hog, a few chickens, three teacups and three saucers, three plates, an iron kettle and two or three pans. No, I didn't have any spoons at first. No, we didn't have a stick of furniture. Asa soon made some wooden benches, a table and a "Hoosier" bed. What's that? You don't know what a "Hoosier" bed is? Well, I never went to school a day in my life, but seems like I know a lot more than these people that claim they are school-educated. A Hoosier bed is made of peeled poles fastened to the walls of your log cabin. It has pole slats and a couple of deer skins over it with a straw or corn husk mattress. In those times a woman generally had 10 or 12 children and did the housework, made the clothes, knitted all the socks and stockings and carded and spun and wove and dyed her own cloth. I used to dye my cloth with maple bark or copperas. If the women of today who are always getting new dresses had to comb the wool and card it and spin and weave and dye the cloth I kind of think they would wear a fig leaf like Eve did. I always had my hopper full of hardwood ashes and I saved all my grease. I made all my own soap. Yes, we worked hard, but I believe both men and women today work too little. The women lay around and get fat and the men get into mischief. We have too many divorces. More children and good hard work would cure a lot of that kind of trouble. We used to be too busy to fret or worry. Work is good medicine. When you can do all the work by pressing a button you have too much idle time on your hands to hatch up some kind of deviltry. Idleness makes a person restless and dissatisfied. Susanna Johnson Peterson, quoted by Fred Lockley, "Oregon: In Early Days," Oregon Journal, Portland, May 31, 1915, page 6 H.S. GIRLS START CRUSADE AGAINST MODERN STYLES

A back to normalcy movement has been started in the high school through

spite work on the part of the girls towards the boys and the youths on

their part retaliating in kind, and there is no telling just where the

feud will end, but so far it has convulsed all Medford with laughter.

The superintendent and faculty try to put on serious faces and frown on

the extravagant action of both sides, but ever and anon glide into some

out-of-the-way nook to give vent to their real feelings.Recently Miss Margaret Cottrell, member of the faculty who has charge the Y.W.C.A. activities, asked the boys to write their opinions of the modern garb, style and facial makeup of the girls. The masculine element of the school went at this very distasteful task with avidity and use of strong and superlative language. What they didn't say about the girls wearing short skirts, low necks, hair over ears, fancy stockings, paint and powder would not be worth reading. These written answers were read to the girls by Miss Cottrell yesterday with the consequence that the fair ones waxed more indignant the longer they talked and thought over the horrid criticisms. Hence it was that [as] a rebuke to this masculine criticism and to show the boys that they were not so smart as they thought themselves, about fifty of the young ladies came to school this forenoon garbed in the plainest and most old-fashioned clothing they were able to find, hair done up plain and carefully brushed back from the ears, and with an absence of powder, paint and rouge from their faces. Did this faze the boys? Far from it. They had a card up their sleeves, owing to the fact that someone had tipped them off last night to the girls' plans. Hence they, too, appeared at school today in a very plain garb, wearing ranch or hunting boots, old-fashioned turndown collars and the like. Some of them were so grotesquely costumed that they were ordered home by the faculty. The next move is up to the chagrined girls. "I fear it won't last," said Miss Cottrell today, "but the girls look very sweet and the absence of makeup is particularly refreshing." Medford Mail Tribune, March 24, 1921, page 8

MODERN INVENTIONS OMEN LAST DAYS,

Modern inventions and increase of knowledge were to come in the last

days, says the evangelist. Hope of man in all generations is soon to be

realized, averred T. L. Theumler at the canvas pavilion last night. "We

may not know the day nor hour when the Lord will come, but we may

recognize the omen of the coming day. The world has moved so rapidly

during the present generation, and such manifest progress has been

made, wonderful inventions multiplied, the advantages for learning so

increased that we have abundant evidence that the coming of Christ is

near at hand," so declared T. L. Theumler, the evangelist in his

lecture, "The Signs Seen in Medford of Christ's Coming."SAYS EVANGELIST "Reflecting open the ages of the past, and viewing the marvelous progress of our day in the light of inspired prophecy, the conclusion is forced upon us that our age alone fits the prophetic mold, and has been especially singled out by Providence," he continued. "All the great lines of prophecy have their focal point in our age, so that we in a special way become a subject of prophecy. More than twenty-five hundred years ago God sent His angel to His prophet Daniel with the instruction to 'shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge be increased.'--Dan. 12-4. "The world has now reached the time of the end, and according to Daniel's words, many would run to and fro, and knowledge be increased. One hundred years ago the world was moving along in about the same slow, easy way that it had been for more than nineteen centuries: our parents rode from city to city in the stagecoach, and their mode of living was decidedly simple. The open fireplace with the swinging crane was utilized for the preparation of the meals, candles were used for lighting purposes, common industries were carried on without the assistance of machinery and the three 'Rs' were considered by the masses to be sufficient education. "All is changed now, our homes are equipped with modern conveniences, and labor is reduced to a minimum. Every little hamlet and village possesses a high school, and both hand and intellect are trained along scientific lines. A generation ago messages were sent by courier, which at best was a very slow method, but now we can send a message to China or India from Medford more quickly than we could a message 25 miles at that time. "A mention of the possibilities of wireless telegraphy 25 years ago would have aroused the ridicule of the scoffer. Recently a ship in the South Atlantic sent a message by wireless and it was picked up at Arlington, 5000 miles away. If mechanical instruments of this sort can be devised to send and receive messages how easily can the ear of the Omnipotent God, the author of science and the creator of all, hear the cries and prayers of his children upon the earth. Science proves the existence of God. and His word will be fulfilled, as the signs abundantly prove. All this wonderful progress has not come about in this generation as a 'happen so,' but very decidedly in the providence of God. Christ declared that the gospel of the kingdom or of His second coming 'shall be preached in all the world for a witness unto all nations and then shall. the end come.' The inhabitants of the world must hear the message and the invitation of Christ's second coming. and to this end the wonderful inventions of our age become instruments of communication from God to man. "The printing press is utilized to print the Bible; yes, the first book printed was the Bible. A short time ago one of the Gutenberg Bibles was sold at auction in New York City at $50,000, the largest price ever paid for a single book. The railway and steamship lines carry the printed page, together with the living missionary, to the uttermost parts of the world. God has caused these inventions to be brought into existence for the purpose of giving the gospel to all the world, and notwithstanding that man is utilizing them for selfish interests, yet God's purposes will eventually be fulfilled. "The newspaper, which is the product of the printing press and the greatest educational medium in the world, could become the most potent factor in communicating the gospel of Christ and the news of His second coming--the most sublime event of the ages, the consummation of the hopes of the children of God--yet this, the greatest news story in all the world, is almost barred from the news columns. "God will nevertheless, however reluctant man may be, accomplish His purpose in declaring the news of His second coming in this generation, and He will cut the work short in righteousness." The subject this evening is "The Origin and Destiny of Satan." Medford Mail Tribune, July 10, 1922, page 4  Advertising postcard, circa 1925 WHY STUDENTS ARE STUPID

Forty

years ago and more, when the

American boy or girl went to college, it was to satisfy a desire for

education. A student of the last generation who went to college found

little lure in the social end of the school; organized intercollegiate

athletics did not draw him at all. There were none. If he was a country

boy, he came from a family in which there were a few well-read hooks.

If he was a town boy, he came from a family where there was a slightly

wider environment of books. But books inspired him. Books and a love of

reading, the desire to widen his mental horizon by getting into the

knowledge of his generation and the wisdom of the ages, furnished the

primary urge that sent the American boy or girl to college until thirty

years ago.By William Allen White (From The New Student) During the last twenty years, two things have happened: First, the colleges have become tremendously attractive to youth, quite apart from the course of study. Second, the rise of the economic status of the average American family has made it possible for thousands of young people to go to these attractive colleges who have no cultural background whatever, who are not interested in books and reading, and who regard education as merely an equipment for making a living. Hence we have the hordes of stupid, ineducable college students. The college spirit, outside of college athletics, society and hooch, never touches them. They are strangers to the academic life--as isolated and remote as the wild savage of the forest from all that went with the cloistered life in our old American collegiate tradition. Perhaps the college softens them a little. Perhaps seeing the books in the library and thumbing and memorizing the texts for their classrooms does pull off some of their feathers and rub off some of their barbarous paint. Perhaps they will make homes in which the Cosmopolitan and Motion Picture Magazine and sets of uncut and unread books may decorate the rooms. So perhaps their children, feeding upon this poisoned pabulum, will get some inkling of the love of books and the desire for things of the spirit. Perhaps in another fifty years the college will be an influence in the higher life of the state and of the nation. But just now the college is the haunt of a lot of leather-necked, brass-lunged, money-spending snobs who rush around the campus snubbing the few choice spirits who come to college to seek out reason and the will of God. State College News, New York State College for Teachers, Albany, February 15, 1924, page 4 Tuesday morning I met one of our early pioneers of this section, Mr. J. S. Vestal and his son, Artie Vestal of Reese Creek, at the W. L. Childreth blacksmith shop, who was there having some work done, but the job was about completed so they hurried off for home without my spending much time with them. It seems as though, since almost every farmer has an automobile, that they have acquired the habit of rushing to town, rushing through their business and leaving for home without taking a thought of the pleasure we used to have in spending a few minutes in social life, and after we have rushed through life, look back and see how foolishly we have spent it. A. C. Howlett, "Eagle Point Eaglets," Medford Mail Tribune, February 23, 1924, page 3 "No, indeed; I haven't forgotten how to dance. I danced on my 83rd birthday, to celebrate the occasion," said Mrs. V. S. C. Mickelson, when I visited her at her home in Ashland recently. "A good many of the young women of today are a pampered, self-indulgent, helpless, complaining lot. For the past 11 years I have lived all alone. I do my own housework, cook, bake, clean house, do my own washing, and work in the garden; so I have no time to sit around and feel sorry for myself and indulge in nerves or tantrums I was never a nagger, a calamity howler or a complainer. I have always been too grateful for health and the possession of all my faculties to moan over my sad lot. In fact, sunshine has always appealed more to me than gray clouds or weeping skies. I not only work with my flowers but my garden comes pretty near to supporting me. I sell eggs and chickens and with the money I buy the few things that go on my table that I do not raise." Victoria St. Clair Chapman Mickelson, quoted by Fred Lockley, "Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man," Oregon Journal, Portland, September 1, 1924, page 6 MODERN CHILDREN BEHAVE WELL

The world

is moving too

fast; there is too much going on. People are apt to plunge in their

scramble for a position in the life of speed. There is too many places

attracting spare time, there are too many worthless offerings to sap

the pocketbook, the nervous system and the home attentions. There is so

much going on that it becomes a necessity to neglect business, home,

schools and religious duties in order to keep up with the amusements

and swift goings of our neighbor. The whole world is tired out, and

only hysterically pepped up on false energies characteristic of this

hurry, speedy, excitable era of civilization.

Much

has been said derisively about the flapper and cake-eater, and possibly

justifiably so, but now we have a little information that goes to their

defense, proving there must be two sides to all arguments.

TOO MUCH GOING ONGrandmothers who gasp in astonishment at the flapper puffing a cigarette while sitting scantily clad in the anteroom of a dance hall had better save just a bit of breath to withstand another gasp. The records of the cake-eaters and flappers attending high school today compared with those of the boys and girls of years ago might make the elders a little pink about the ears, particularly the more critical ones, the Kansas City Board of Education announced recently. Playing hooky is becoming passe, tardiness is greatly on the decline, and the behavior of the students is such that the old-fashioned hickory stick is being used for a chart pointer, the gist of the board's report says. Back in the old days, we all can remember and confess that only the "sissies" made a perfect attendance record and all that "mother's darling girls" refused to stay away from school occasionally. Truant officers were an absolute necessity in those days, and they were kept busy keeping the young truants in line and marching them back to the schoolrooms. But now times and things have changed, as grandmother would say, in her argument in denouncing the wild practices of the 1924 youth and miss. The truant officer has become an "attendance officer," and his duties mainly consist of investigating homes and assisting students who would be unable to attend otherwise. Tardiness is becoming almost nil, the report shows, and the cake-eaters and flappers who are being admonished they are setting too fast a pace might reply: "Yes, to school." The marks for punctuality are much better in the last couple of years than they were in the earlier years, according to the figures in black and white, other arguments notwithstanding. And then, too, while the flippant miss and her pastry-consuming friend might be burning up the boulevards on the outside, teachers report that the conduct of the pupils in the classrooms today can be admired. Such tricks as shooting paper wads and placing a tack on the teacher's otherwise soft chair are rarely indulged in, and more rare than that is the compulsory use of a stick to make a pupil behave. All of which goes to prove both side of the argument that times and things have changed. Ashland Daily Tiding, September 16, 1924, page 2 So It's Happy New Year

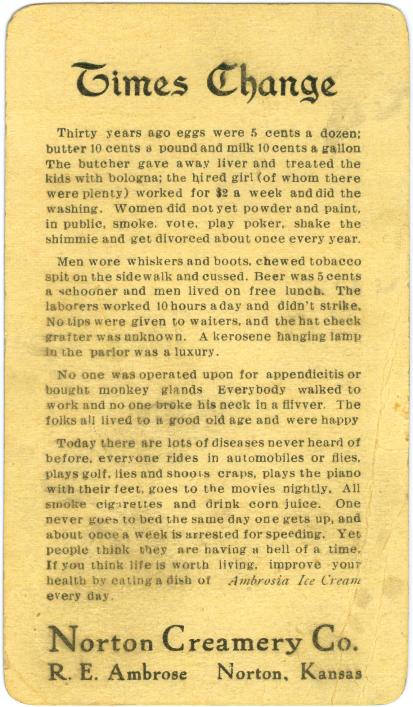

To the Editor: Thirty years ago I remember when eggs were 3 dozen for

25¢, butter 10 cents per pound, milk was 6 cents a quart, the butchers

gave away liver and treated the kids with bologna; the hired girl

received two dollars a week and did the washing; women did not powder

and paint (in public), smoke, play poker, or shimmy; men wore whiskers

and boots, chewed tobacco, spit on the sidewalk and cussed. Beer was 5

cents a glass and the lunch free. Laborers worked ten hours a day and

never went on a strike. No tips were given to waiters and the bad check

grafter was unknown. A kerosene hanging lamp and a stereoscope in the

parlor were luxuries. No one was operated on for appendicitis or bought

glands. Microbes were unheard of; folks lived to a good old age and

every year walked miles to wish their friends a Merry Christmas.Today you know everyone rides in automobiles or flies, plays golf, shoots craps, plays the piano with their feet, goes to the movies nightly, smokes cigarettes, drinks, blames the H. C. of L. on the Republican Party, never go to bed the same day they get up, and think they are having a hell of a time. These are days of suffragetting, profiteering, and Prohibition, and if you think life worth the living I wish you a happy New Year. W. G. NOONAN.

"Communications," Medford Mail Tribune, December 31, 1924, page 4Central Point, Ore. MODERN YOUTH NO WORSE THAN YOUTH LONG AGO

DENVER,

Colo., Feb. 3.--The age-old "superiority complex" of the older

generation towards modern youth was toppled from its pinnacle today by

Bishop Edwin H. Hughes of Chicago, in an address on "the church's

responsibilities to youth," before the Denver council of the Methodist

Episcopal Church. He compared "bobbed hair" with the "bangs" of the

'eighties; short skirts with the "hoop skirts," and the modern

automobile and motion pictures "crazes" with the skating rink and

bicycling fads of days gone by.

The censure of "young folks" is not peculiar to the present day, was the assertion of Bishop Hughes who declared he could track back "this misunderstanding to 2000 years before Christ," and could name "epitaphs on monuments 2000 years old in which old kings declared that their young people were going over the precipice to destruction." Despite the complexity of the present day, Bishop Hughes warned the older generation that they could not "fold their hands, sit back and talk as if they were angels when they were young." Bishop Hughes in his address upset many of the rules of the "judgment of human nature," stating that he found no truth in the supposition that a man was wicked in character "if he could not look one squarely in the face," and that a man with a squint in his eye had a quirk in his moral nature. Race prejudice was assailed by Bishop Hughes in the statement that "God only knows what is going to happen to the white people if we continue to keep the colored ones against us. The only yellow peril the white people need to fear is the yellow streak in their own lives." Medford Mail Tribune, February 3, 1925, page 6

THE MODERN SATURDAY NIGHT

What

people do on Saturday night is a means by which their character and

traditions may be judged, according to a Dayton, Ohio, newspaper. It is

true that the times are changing, and that with them Saturday night

customs are changing also. It continues:

"Every Saturday night in a very true sense offers a time for a checking-up process in the lives of individuals or collectively of families. There was a time in the history of this people when a solemn hush came over the family as the twilight hours fell upon the city and countryside. Shoes were blackened, cooking was finished, the family altar was set up, and whole families waited in a true religious manner for the dawn of the Sabbath day. But Time is a relentless sort of machine. It crushes ambitions, annihilates traditions, destroys our fondest dreams. Today much of the solemnity which in former days was a part of Saturday nights has disappeared, and one and all, old and young, give themselves over to thoughts of relaxation from the strenuous work of the preceding week and surcease from worry. In a sense it would be a magnificent thing if we here in America could get back to some of the old-fashioned ideas which we have held relative to Saturday nights. If we could sum up, for example, our week's accomplishments and plan for the coming days we could go forward to new and greater tasks, we should gain new inspirations for service to ourselves and to others. This may sound idealistic, but it is the sort of idealism that we need more and more as we progress." The view taken by this Dayton writer is a righteous one. It is true also that the spirit of idealism of which he speaks is coming to play less and less a prominent part in the civilized world today. Ashland Daily Tidings, February 28, 1925, page 12 LEGISLATOR BELITTLES GRADUATES

Sen. Eddy Declares Half of High School Students Cannot Place an Apostrophe, Or Figure Out a Promissory Note--Lack Fundamentals.

PORTLAND,

Ore., Oct. 16--(AP)--Sweeping declarations that 50 percent of the

Oregon high school graduates do not know the difference between

"advice" and "advise," "effect" and "affect," and cannot correctly

place the apostrophe in possessive plurals, were voiced here today by

Senator B. L. Eddy of Roseburg before a gathering of high school

teachers and principals and other public school men and women of this

city. Following Senator Eddy's remarks, a warm controversy arose at

this first public hearing in Portland of the course of the study

commission created by the last legislature.

The commission, appointed by Governor Pierce, included Senator Eddy, Dr. C. J. Smith of Portland, and Professor George H. Alden of Willamette University, Salem. Dr. Alden presided at today's meeting. Average Oregon high school students are not sufficiently grounded in fundamentals, especially in English, grammar and mathematics, the Roseburg senator complained. He suggested as a remedy a reconcilement of curricula, the restriction of students' privileges to choose elective studies and a close adherence to the fundamental branches. He would eliminate from high school school courses all study of social problems, civics, political economy and subjects "in the nature of art." He opposed high school credit for music lessons taken outside of the school and home economics courses which, he said, only taught the girls to make angel cakes, nougat and fudge. The existence of correspondence schools is an indication that high school graduates realize they are not prepared for the world, Senator Eddy declared, saying it was surprising that high school students should take business English courses in business colleges. "If you give a high school graduate a promissory note with some payments endorsed on the back of it and ask him to determine the amount still due on it, you might as well ask him to translate the Iliad in the original Greek," the Roseburg man asserted. Meager applause which followed the conclusion of Senator Eddy's talk came from a small group of men. Women composed approximately two-thirds of the attendance, which reached 150. Following Senator Eddy's report, Professor Alden invited open discussion of the matter, declaring that "whatever you as educators think, it must be remembered the laymen help pay the bill, and they will have something to say about how it is spent." Superintendent Rive of the Portland schools called attention to the fact that most of the subjects upon which Senator Eddy would lay stress are just as true of colleges, and he questioned placing entire blame on the high schools. R. R. Tucker, superintendent of public instruction, characterized Mr. Eddy's talk as an "extravagant picture." School people are best fitted to wrestle with the problem of school curricula, he declared. Dr. DeBuck of the University of Oregon, head of the research department of the Portland public schools, declared that the problems brought up by Senator Eddy were matters of long controversy in the educational field and that there is an abundance of material to be found in them. "You can't settle problems by counting noses, and that is all that public hearings amount to," he asserted. "Before trying to apply any remedy, the thing to do is to find out exactly what is wrong." Medford Mail Tribune, October 17, 1926, page 1 POEM IS WRITTEN IN HONOR OF

WIDELY KNOWN PIONEER

At

the recent reunion of Southern Oregon pioneers, John B.

Griffin,

pioneer resident of Kerby, read a poem which he had written in

commemoration of the 93rd birthday anniversary of "Grandma" Lewis, who

is 93 years old. The poem written by this widely known early settler

aroused much interest among the trail blazers and their wives who

attended.

His poem follows: TO A PIONEER

Come,

ring the bell for dinner

Ashland Daily Tidings, October

22, 1926, page 10And all rejoice with me. For this is Grandma's birthday, And she is ninety-three. Seventy-three years ago, she came To the land of the setting sun And ever since that time Has lived in good old Oregon. Wonderful changes have taken place, Since Grandma crossed the Plains; Then they traveled with ox teams; Now they come on trains. They also travel through the air And under the ground they walk; They travel through the water And eat and sleep and talk. You can sit in the parlor at night And sometimes through the day And listen to people talking Thousands of miles away. If you go away from home And don't get back till night, And the house is dark as a dungeon, Touch a button--and lo, you have light. If you wish to talk to a friend, Miles and miles away, Just go to the 'phone and call him, And say what you have to say. They used to go on horseback And sometimes had to walk, When they went to church on Sunday To hear the preacher talk. But now they go in autos And get there mighty quick; Have plenty of time to powder the face And make themselves look sleek. Now, Grandma has seen all these changes; And hundreds of others beside; And has lived through wars and pestilence, While millions of others have died. So, gather around the hearthstone And listen to her tell Of things that happened long ago, That she remembers well. Perhaps she'll tell you about the time The stars fell thick and fast; And everyone for miles around Thought their time had come at last. She will tell about the spinning wheels They used in days of yore, To spin the yarn to make the socks That everybody wore. She will tell us how they baked the bread In an oven by the fire, And when it raised up to the lid, It could not get any higher. She'll tell about the husking bees, When neighbors gathered in And husked the corn for Billy Jones And put it in the bin. She'll tell us how the girls those days Made their dresses nice and neat, To button up around the neck And reach down to their feet. But now the girls are different, They make their dresses thin, To reach down only to their knees And barely hide their skin. Some of them have no dress at all, But wear clothes like a man; Perhaps they think it helps their looks, But I don't see how it can. They paint their lips as red as blood And powder to beat the band, Which makes them look just like a ghost That is stalking o'er the land. Now, Grandma don't approve of this; She doesn't like their ways. She would rather see them make their clothes Like they did in the good old days. But, alas, the good old days are gone, They will never turn again. No one will turn the spinning wheel; No ox will cross the Plain. No one will try to bake the bread In an oven by the fire; They'd rather buy it at the store, If the cost is a little higher. No one will help to husk the corn For poor old Billy Jones; He has to sit day after day And husk it all alone. No covered wagon is in sight, As you drive your car to town; They fell to pieces long ago And the wheels have rotted down. No more we'll hear the Indian yell, Nor see a buffalo. The white man butchered all of them A long, long time ago. So now we'll have to bid goodbye To the good old days of yore; The good old days we loved so well, That we'll never see no more. The pioneers are going fast; Their race is nearly run, But then their lives have been well spent; Their work has been well done. The last of them will soon be called To cross the silent river, And land upon another shore To live in peace forever. But hark, the dinner bell is ringing, Let's go and eat with Gran--once more. And pray we may all meet again When Gran'ma is ninety-four. This carnival of spending, this demand for sport, athletics, amusements and popularity is ruining our schools as well as our individual health. The average family certainly cannot afford to send a boy or girl to college where they have to have a dollar ticket every night for a class dance, a fraternity party, a mask ball, a basketball game, a football game, concert after concert, evening gowns, dance shoes, silly hats, striped stockings, gas, gas, gas. It can't linger long. The carnival resembles that of ancient times before the fall of Rome. If a business man refuses to buy a ticket to a ball game, a pee-wee party, a dress rehearsal, a class program or a pink tea, he is counted a grouch; consequently he feels compelled every day to dig up his last cent and stand off the freight bills. Home sweet home is a memory of bygone days, and "where is my wandering boy tonight" includes, as well, the "wandering girl," "wandering mother" and whole "wandering family." But even to the jazz-crazed youth it must be admitted that it really does look silly to him to see a mother of several children travel several miles two or three nights a week to attend a jazz dance and go through the silly, crazy steps and movements while hanging on to the arm of a lad young enough to be her son, or with an old granddad with watering eyes and a silly grin over the imaginary fun he thinks he is having. What heads we are all getting. Where is the money coming from. And still you hear the talk of "hard times," when you approach a firm on a business proposition. Plenty of money for gas, for sport duds, for moonshine at two plunks a pint, and even for skyscraper apartment houses for the homeless and half-million-dollar art buildings and libraries for colleges all over the world and hardwood reception parlors for the sweet girl graduate to entertain her racing car, vaseline-haired suitor awaiting time for the dance or midnight frolic. Where is the remedy? There must be a remedy, or death and destruction will follow failing health and bankruptcy. Many fads, customs, habits and styles lead to the fastness of the age. The fiery youth propaganda put out by Hollywood, the low dress, loud stocking styles hatched by the fast women of Paris, the overworked attention given to athletics instead of the three "R's," the lack of control in the home, the lack of foresight and the lack of regard for the saving habit; too much credit and too much excitement. Too much going on, too many places to go. There is no present remedy. But the life will run itself out. It will take hard times or maybe a general panic, but it is coming. Then, and not until then, will everyone, young and old, get down to business and hard work again. Then will the silly styles be a second consideration, and more hours be devoted to care of self and sensible living. Flaming youth, as it is termed, is having its day, but we all acknowledge that it is a mighty silly age, and old Nero or Cleopatra were not in it. Ashland American, March

25, 1927, page 2

PROPOSES SCIENCE STAY DORMANT IN 10-YEAR PERIOD

LONDON, Sept. 6.--(AP)--Feelings ranging from amusement to amusement

have been aroused in British scientific circles by the suggestion from

the High Rev. Edward Arthur Burroughs, bishop of Ripon, for a ten-year "scientific holiday."