|

|

Gold

Mining in Southern

Oregon For

the Spectator.

Editor Spectator--Sir:

For some time past I have sought an opportunity to redeem my engagement

of writing to you and giving as correct an account of these "diggins"

as possible, for the benefit of your readers. My apology for this long

delay is simply that, on my arrival here, I was necessarily much longer

in getting located and fixed for digging than I expected to be. An

account of a miner's life &c. is unnecessary in this letter,

for

the reason that but a very few of the Oregonians are uninformed upon

that point, not only by reading, but they have personal experience of

the matter, and those who have not will very readily obtain oral

descriptions of it, which cannot but be much more satisfactory and

vivid. The mining on this river at present consists almost entirely of

working the bed of the river; a few, however, are still working in the

banks.

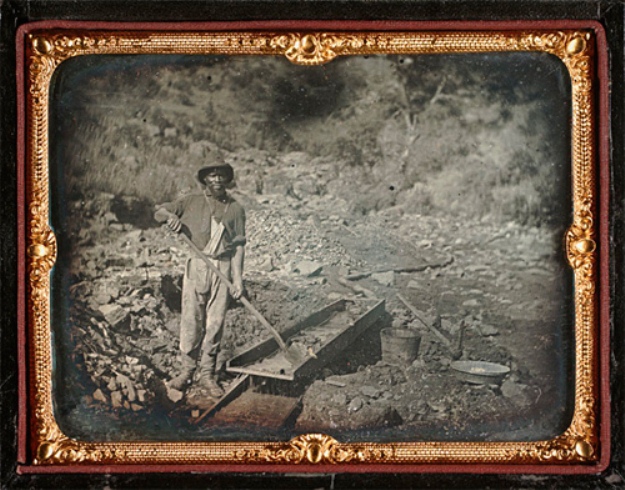

Before any of the dams were ready to take out gold, great hopes were entertained, and nearly all were confident of a liberal and even a large return for their time, expense and labor. These dams are worked by companies of miners, the company varying in number from 8 to 20 or more. A system of speculation was tolerated by the miners here, which, I understand, was not suffered to exist in Lower California, at least when those mines were as new as these. It seems that those who were somewhat in advance of the rush for this river immediately, each for himself, laid claim to a sufficient portion of the bed of the river for from 10 to 20 men to work out in one season, and then, when the working miners came, sold to them shares, the number being according to the length of their claim, asking from $100 to $400 per share, and thereby in many cases making moderate fortunes without a stroke by fleecing from the hard-working miner his honestly obtained and hard-earned gold. A more wholesale imposition upon the industrious miner I never heard of, and am only surprised that such a system of robbery should have been for a moment tolerated or gained the foothold it has. In a majority of cases, however, the condition of the payment was made to be that the purchase money was first to be taken out of the claim, and drawn by the shareholder from the treasurer as the income for his share. The fact of very many of these dams failing in whole, or in part, has very much disappointed the undeserving and in many cases dishonest speculator, and nipped his golden dreams in the bud. I am of the opinion, however, that Scott River--that portion of it which is being worked--is as rich as perhaps any river that up to this time has been worked in California. I may be wrong in this, as my knowledge of Lower California has been obtained from others altogether. Some of the dams are very rich--some pay from $20 to $40 per day--and others from ½ to an ounce per day, while very many will hardly pay for working, and a good many [are] already abandoned, the two last, perhaps, embracing the larger number. The old Goodwin, at present called the Lafayette Damming Company, took out the other day something over $8000, not using the entire day either--as I understand they were moving timbers or something else a small portion of the day. These latter things, however, are always necessary to carrying on the works and must be done. They by no means average the above amount, but the claim is very rich, and those engaged (22 in number) will make a good "raise." If it had not been for a lawsuit with certain other claimants, which cost the company some $3000 or $4000, they would have done something better still. All the dams are troubled very much with leakage water, to a greater or lesser extent, according to the depth of their diggings, which causes much expense and labor to remove. Pumps of different kinds are in use with various success. The Lafayette Company are using a pump propelled by water, the pump consisting of a tight box of the required length, and about 13 inches by 6, one end submerged in the water about 1 or ½ feet. Strong canvas is then prepared of equal width with the box or pump, and the two ends sewed together, two rollers of same width as the pump are fastened one at each end, upon which the canvas rolls. Upon this cloth, at a distance of 16 or 18 inches apart, are fastened blocks, nicely fitting the pump, and when put in motion, the blocks finding water in the lower end of the pump, force it up until it empties itself out of the top, and then runs off in any manner the person desires. This company have two of these pumps, and they are answering a very good purpose. The best and by far the fastest pump I have seen on the river is worked by water power on the "Gipsey" claim, about two miles below Scotts Bar. It is a screw pump, and probably the principle is familiar to most of your readers. This pump was constructed at great expense (some $1200) by Frederick Derrick, the enterprising foreman of the company (at the mutual expense of the company, however). Mr. Derrick is from Rockford, Ill., and some time since in the employ of the N. American Fur Company, and while in their employ builder of Fort Laramie. For his great ingenuity and perseverance in the construction of this pump (which throws the enormous amount of a barrel of water a second), and that too without any of the conveniences of lumber, ready sawed, and with a very poor and scanty supply of tools he receives, and is deserving of, the highest praise and commendation. The gold taken from this river is of the very best quality, and mostly coarse. A short time since, there was taken from the Little Company, the first above the Lafayette, and opposite the town, a solid piece of gold weighing 10 lbs. avoirdupois. I would here caution the reader unacquainted with mining against forming too favorable an opinion of them, and bear in mind that while one man is so fortunate as to find diggings of this description, perhaps 500 may be with some difficulty making even moderate wages, and perhaps half this number hardly paying expenses. It is at present rather a dull time here; those miners whose dams have failed have mostly left for the mountains to hunt winter diggings. It is very confidently expected that rich mines will be found in some of the gulches leading into Scott River. I am myself inclined to that opinion, but do not think they will be found until water comes, at least not to any extent. At this time there is probably three or four hundred miners in the mountains about this river and the Shasta diggings. It is rumored that some small parties have found very rich mines somewhere around here, and I do not credit the tale. [Those stories may have been about the discovery of the Althouse diggings in Josephine County.] It is rather amusing to see the pertinacity with which some entertain this belief. If they see a party of half a dozen or so traveling by themselves, with any appearance of having supplies with them, some who are on the watch will immediately set out and follow them, and the party followed all the time upon the same errand as themselves. I verily believe I could take my horse, and start out at evening with a little manifestation of a desire to be alone, and get a hundred men to dog my steps upon and over some of the most awful mountains ever traversed by a mule! The miners about Shasta are doing very little at present, but the city is being built up very fast, and is already quite a town. Confident anticipations are entertained of doing well about there when the rains set in--I think they will. Supplies are plenty in this country and cheap; flour about 30¢ per lb.; beef 25 to 30¢ lb. on this river, and at Shasta 20 to 25¢ per lb.; potatoes 50¢ per bushel; onions 60¢; clothing plenty and reasonable. The Indians appear to be friendly at present, and we all hope that no difficulty will occur. If you are acquainted with an upholsterer in Oregon who is desirous of going into the manufacture of mattresses, just send him out here; he will find plenty of hair, some curled and some not--he can make his fortune! The Oregonians must not depend too much upon receipts of gold dust from these mines to make trade lively this winter, for the larger portion of it goes and will go to California. I occasionally see a Spectator here, and would like to see them much oftener. We are compelled to lead a kind hermit's life here, which to those accustomed to living in old settled countries where news is plenty, and received by lightning, is at first rather dull and tedious--but as I have made my bed, so will I lie on it. Yours,

Oregon

Spectator, Oregon

City, October 21, 1851, page 2PICK AXE. Personal Experience in Quartz

Mining.

The Jacksonville (S.O.) Sentinel,

commenting

upon a recent quartz mania that appears to have broken out about Yreka,

supplies the following result of personal experience to the common

stock of information on quartz mining in the state. It may be found

useful to dabblers in quartz elsewhere:

"We have bought some experience in quartz, and paid rather liberally for it too. But it was when this species of mining was in its infancy in California, and wiser and more scientific heads than ours showed conclusively in theory that to engage in it was but another name for coining money, where the precious metal was furnished free of cost. Stern, uncompromising practice, however, developed that the coining operation was simply reversed. It was no more than furnishing to others the money already coined without any other return than that costliest of all human lessons--experience. Since then we have paid more attention to quartz and its queer freaks, and as attention was about all we could pay, we received at least the benefit of better knowledge of everything pertaining to it as compensation for the time bestowed. Therefore, we now profess to know something about our subject, and without going into a lengthy dissertation, will give the result of experience upon a leading characteristic of gold quartz. "An almost infallible rule to be observed in quartz veins is to quickly abandon those leads which 'crop out' most abundantly, as the gold is rarely, if ever, found to reach much below the surface earth in them. It is not the richest veins which reveal to the eye the most gold and a continuous yield of the shining metal. The most lucrative quartz mines in California are those which prospected poorly at first, and in which 'the color' was not visible to the eye in any of the surface rock. To test the quartz fairly it is necessary to get out tons of it first, and then submit pieces taken here and there along the depth of the shaft to skillful assay. If the gold is found more plentiful with increasing depth, there is little risk in going to the expense of adequate machinery to work the mine. But if the yield diminishes from the top until a few feet down, that vein will only result profitably by doing with it as Brigham Young did with the troops--letting it 'severely alone.' Those who chance to own a good-paying vein, and are too pinched in circumstances to afford the outlay for a steam engine, etc., can manage very well with the ordinary Mexican arrastra until their earnings enable them to purchase more costly and powerful machinery, provided their claim promises sufficiently exhaustless to warrant such application and expenditure. But it is quite invariably a suicidal and ruinous enterprise to become involved in a debt for these appliances at the outset, with nothing more substantial than a 'good sight' to provide for after payment "We offer these remarks at this time because recently there has been a good deal of gold-bearing quartz picked up about our own county, and some in Josephine (Southern Oregon), and already parties are out prospecting for leads. The specimens exhibited are of what we might call a healthy richness; that is, they are not profuse with great flakes and veins of gold, but rather indicate that the best is yet to come from far below. Where these are found there are undoubtedly extensive leads of surpassing and exhaustless yield, nor can they long remain undiscovered, with the energetic efforts that are being daily made to find them. From what we have seen of the region, we are profoundly convinced that there is an abundance of handsomely paying gold quartz to be found in it, and this is sufficiently evident from the discoveries recently made." San Francisco Bulletin, November 3, 1859, page 1 JACKSON COUNTY

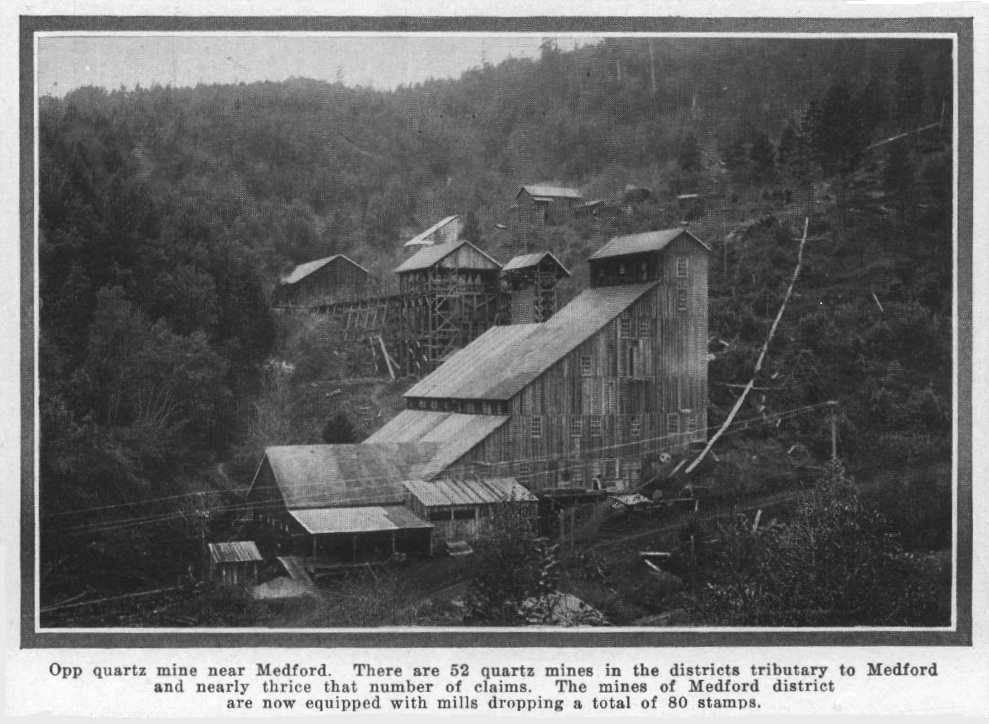

I am

indebted for much valuable

information concerning this county to Mr. Silas J. Day, of

Jacksonville, whose character and long acquaintance with the

neighborhood give ground for confidence in the correctness of his

statements, many of which are also confirmed by my personal observation.The population of the county is about six thousand six hundred, of whom six hundred are Chinese, principally engaged in mining. The number of white miners, according to the books of the county assessor, is five hundred. The latter receive, when hired, from $2.50 to $3 coin per day. The wages of a Chinese laborer are $1.25 to $1.50 per day, or $35 per month. The following is a brief account of the principal mining districts in the county: Jacksonville district, including both forks of Jackson Creek and its tributaries, was organized in 1851. The mines hitherto worked have been placers, with some coarse gold. Applegate Creek, ten miles in a southerly direction from Jacksonville, is a considerable stream, on which a sawmill has been erected. It is a tributary of Rogue River. The district of this name was organized in 1853. The mining operations on Applegate Creek have been quite extensive. The gold is found mainly on the “bars” of the creek, which for a distance of four miles were very rich. They are now principally worked by Chinese. Water is obtained from a large ditch brought from the creek four miles above the bars, and now owned by Kaspar Kubli. Sterlingville district, about eight miles due south from Jacksonville, was organized in 1851. This has been, and is still, a thriving mining camp. The gold in the placers is coarse. The supply of water, however, is limited, as there is no ditch in the district which taps any considerable stream. Bunkum district, on the other hand, a southern extension of Sterlingville district, has an abundant supply of water during most of the year, brought in three ditches from the North Fork of Applegate Creek. Foots Creek district was organized in 1853. The stream from which it takes its name is a tributary of Rogue River, situated about fifteen miles northwest from Jacksonville. The mines are coarse gold diggings. Evans Creek and Pleasant Creek districts are contiguous to each other, about ten miles north of Foots Creek. The coarse gold diggings of these districts are worked principally by the hydraulic process, for which the necessary supply of water is furnished by the streams named in abundance during the rainy season. Both these districts were organized in 1856. Forty-Nine Diggings, eight miles southeast from Jacksonville; organized in 1858. The gold is inferior in quality, and worth only about $12 per ounce. Water is supplied by a ditch from Anderson and Wagner creeks. The mining laws of all these districts are copied from those of Yreka, in California. The tax on foreign miners (by which only the Chinese are understood) is $10 annually per capita. There is also an annual poll tax of $5 on all mulattoes, Chinamen, and negroes. The first discovery of gold in Jackson County is said to have been made in the autumn of 1852, by James Clugage, on Rich Gulch, a tributary of Jackson Creek. Both in the gulch and in the creek large nuggets were, in the earlier days of the mining industry of this neighborhood, frequently found. One piece of solid gold, worth $900, was taken from the latter stream, and many were obtained ranging in value from $10 to $40, and up to $100. These discoveries led to the development of a considerable mining industry, in which, however, no great amount of capital was invested. The claims in the county are, with the exception of the bars and a few quartz claims, mentioned below, generally placer and gravel diggings. The heavy wash gravel ranges from two to twelve and even twenty feet in thickness, and contains a large amount of stones, and even rocks of considerable size. This is especially the case on Jackson Creek. The bedrock is slate or granite--the former predominating. Water is supplied principally by the rains of the wet season, which swell the local streams. There are few mining ditches in the county, and none of great magnitude, the length being generally from one to four miles, and in no case exceeding the latter figure. The mines are therefore directly dependent upon the duration of the season of rains. This lasts usually from December 15 to June 1. The mining season for the year ending June 30, 1869, was, however, here, as elsewhere, a very short one, owing to the extreme dryness of the winter. The season opened about the 10th of January, and was over by the middle of May. When I visited the county, early in August, nothing was doing except by some of the Chinese, who were painfully overhauling the dirt heaps and carrying the earth to water. The average annual product of Jackson County in gold dust for the last five years has been, according to good authority, $210,000. I estimate the product for the year ending June 30, 1868, in spite of the brevity of the season, at $200,000, since the patient labor of the Chinese, of whom there are a considerable number working for themselves, has made up the deficiency of the season. They have produced not less than $75,000 during the year referred to. The product for the calendar year 1868 is practically the same as I have given, since the period of active operations fell wholly within 1869. Some very rich quartz ledges have been discovered in this county, and I do not doubt that this, like so many other placer-mining regions, will eventually become the scene of extended deep-mining operations. No quartz veins, however, so far as I could learn, have been worked in Jackson County with capital, perseverance, and judgment adequate to fully prove their values, though in several instances large profits have been realized from operations near the surface. One of these instances is presented by the celebrated Gold Hill vein, situated ten miles northwest of Jacksonville, and discovered in January 1859. The ore is white, almost transparent quartz, and, in the pocket first exposed, was highly charged with free gold. Some rock taken from the ledge was so knit together with threads and masses of gold that when broken the pieces would not separate. The vein was worked rudely for a year, and the ore crushed principally in an arrastra. The sum of $400,000 was thus extracted, besides a large amount of extremely valuable specimens, one of which was presented by Maury and Davis, merchants of Jacksonville, to the Washington Monument, and now, I am informed, occupies a place in that structure. But the pocket became exhausted; subsequent operations failed to find paying rock, and the work has been suspended for some years. The property is now owned by a few shareholders, who intend to resume mining at some future time. The Fowler lode, at Steamboat City, twenty miles from Jacksonville, is also at present lying idle. This ledge was very rich near the surface, where the rock was considerably disintegrated. The contents of a rich chimney or pocket were extracted, and crushed in arrastras run with horse power. Major J. T. Glenn, one of the owners, says $350,000 were taken out. Arrastras were erected at a ledge on Thompson Creek, a tributary of Applegate, to work the ore extracted, but the rock did not pay, and it was finally abandoned. The Shively ledge, on a tributary of Jackson Creek, has had a similar history. At present there is but one quartz vein worked in the county. It is being developed by a few men as a prospecting scheme. They carry the quartz about a mile, to the Occidental mill, where they have already had about 100 tons treated, realizing about $1,000, or $10 per ton. There are three quartz mills in the county, all driven by steam. The Jewett mill, on the south side of Rogue River, was erected sir years ago in connection with a ledge of the same name. It had eight stamps, and 32 horsepower. The investment was not profitable, professedly because the gold was too fine to be saved, and the mill is now a steam sawmill. A mill similar to the foregoing was put up seven years ago at the forks of Jackson Creek. It cost $8,000, and was intended for custom work, but did not pay, and is now owned by Hopkins & Co. as a sawmill. The Occidental mill, on the right fork of Jackson Creek, was built four years ago by a company at a cost of $10,000. It has ten stamps, and 40 horsepower, was made at the Miner’s foundry, San Francisco, and has a daily crushing capacity of 20 tons. The machinery includes two rotary pans. The cost of mining materials in this county is not excessive. Lumber is worth at the mill from $18 to $22.50 per thousand feet, according to quality; quicksilver, $1 per pound; blasting powder, 33 cents per pound. Freight is generally shipped from San Francisco to Crescent City, California, and hauled from there in wagons to Jacksonville, at a total expense, including commissions, insurance, etc., of about 5 cents per pound. This enhances the cost of machinery and of some supplies. As a general rule, Jackson County receives no freight overland from Portland or Sacramento. There are several good salt springs in the county. One at the headwaters of Evans Creek has been worked with profit for several years past by Messrs. Brown and Fuller. The salt is said to be white and pure, and commands a good price in the local market. Two beds of mineral coal have been discovered in the county. One on Evans Creek, about ten miles from the salt- works, produces a superior coal, which is used by the blacksmiths of the county. It is comparatively free from shale, and is locally known as anthracite. The bed is owned by Mr. R. H. Dunlap, of Ashland. Large quantities of iron ore occur in many places throughout the county, on the surface of the ground. Some specimens from Big Bar, on Rogue River, were analyzed in San Francisco, and found to be quite pure. Cinnabar is reported, but not in paying quantity, from Missouri Gulch, a tributary of Jackson Creek. Rossiter W. Raymond, Mines and Mining of the Rocky Mountains, the Inland Basin and the Pacific Slope, New York 1871, page 214 AN INTERESTING REVIEW--ACTIVE PROSPECTING AND NEW DISCOVERIES IN MANY QUARTERS.

Gold-bearing

quartz exists in very many localities in Jackson, Josephine and Douglas

counties, and the two former have been the scene of considerable mining

operations within the last twenty-five years. The first quartz

discoveries in Oregon took place in 1859 upon Jackson Creek, when a

deposit containing one or two thousand dollars' worth of the precious

metal was unearthed by two brothers named Hicks. In the latter part of

the same year very rich quartz was found on Gold Hill, close by Table

Rock, in the Rogue River Valley, and $150,000 was taken out. This mine

as well as the first named, and in fact all those of which we have to

speak, was of the sort called a "pocket" lead, where all the gold was

found in a very small space in or on the vein, the rest of the quartz

being barren or very nearly so. This, the great characteristic of mines

of this class, was not recognized at the time of these discoveries, nor

has it been fully understood or appreciated yet. This mine, the Gold

Hill claim, was owned at first by its discoverer, Graham, with Tom

Chavner, John Long, George Ish and James

Hay. Henry Klippel and Col.

John Ross afterwards bought in. A large part of the find consisted of

"float" (loose pieces of rock), which were in a cavity right over the

ledge, or had rolled down a dry gulch. Hundreds of people prospected

here immediately, and nearly the whole population gave up every

occupation except that of watching the fortunate locators as they

picked up choice chunks of quartz with gold visible all through it. Two

arrastras were at once put up, and their output amounted for a while to

1,000 ounces of retorted gold each week. Dissatisfied with this, a mill

was projected, but it proved unsuccessful, as the pocket was nearly

exhausted before the stamps began to drop. The total amount of gold

taken out was about $150,000, which was all contained in a portion of

the vein twenty feet long, ten feet deep and two feet thick. Hence it

was a true pocket vein. All the remaining portion of the lead has been

found to be barren. However, it has not been thoroughly prospected as

yet in all its accessible parts. Work on it ceased long since.

GOOD

YEAR IN MININGGreat as was the yield of the Gold Hill vein, it was thrown in the shade by the product of the Fowler mine on Steamboat Creek, a tributary of the Applegate. This vein lies near the California line. Its gold is found disseminated through a larger proportion of rock, but it still possesses the essential character of a pocket vein, although it has been worked as a milling lead. This claim was owned by W. W. Fowler, G. W. Keeler and some others, and was worked for over three years, the rock being put through arrastras. The yield per ton was as high as $2,000, and 1,400 ounces were taken out in a single week. The whole yield is thought to have been over $300,000, which makes this the most productive pocket mine on record, as far as is known. In the vicinity of Gold Hill several quartz claims have been worked with success. The principal of these were the Blackwell, the Swinden, the McDonough and the Schumpf veins. On Jackson Creek, very close to the town of Jacksonville, the Holman, the Davenport and other claims were worked, mostly in 1860, the time of the chief excitement in quartz. The Jewett mine, across the Rogue River from Grants Pass, was also worked in the same year and paid many thousand dollars. The above includes the greater number of successful quartz claims in Jackson County, and it has to be observed that the greater part of the work was done upon them in 1860. Subsequent developments have affected little. Down in Josephine County some gold quartz has been found. The Enterprise mine on Althouse Creek was worked with profit for several years, the rock yielding about $25 per ton. In 1875 the so-called Oregon Milling Company got possession of the ledge and built a mill at Browntown, near Althouse, but failed to make money. Several quartz ledges lie nearby, none of them having been worked to any extent. In the northern part of Josephine County, near the railroad line, lie several well-known quartz claims, some of them esteemed of value. The Lucky Queen is one of them, but it has thus far belied its name. It is situated on Jump-off Joe Creek, and has been extensively prospected, with great promises of richness. It has a mill of ten stamps. Upon this mine and the Esther, or Browning claim, on Grave Creek, has been done more work than has been put on any other quartz claim in southern Oregon since the exhaustion of the Fowler lead in 1864. In various other localities in Jackson and Josephine counties auriferous quartz has been found, notably on Galice Creek, Williams Creek, Foots Creek, Evans Creek, etc. There have been "rushes" to various points, notably to Galice Creek in 1874, where several hundred locations were made on some big ledges 200 or more feet wide. The real history of quartz mining, however, is confined to the years 1860 and 1863, during which time all the most important discoveries were made, and particularly the first-named year. The total gold product of southern Oregon, as far as can be ascertained, includes about $700,000, which was derived from quartz mines, and of this not less than 95 percent has been taken from pocket veins. The chief grounds for expecting other and even more extensive developments of auriferous quartz lie in the fact that at least two-thirds of the above sum was taken out of the mines in one year, since which the art of quartz mining has been suffered to languish with only an occasional small discovery to keep it from falling into oblivion. It is not possible that the extensive region could have been entirely exhausted of its mineral wealth in so short a time, and by so unskilled a generation of miners as inhabited it. Quartz mining was then a new and almost untried art, and the resources for this sort of mining were small and precarious. Pocket mining has in some sections become an art by itself, demanding knowledge, skill and care for its proper direction, and when associated with these its pursuit becomes successful in a high degree. The principles of that art are simple. They consist in following the quartz vein to its intersection by a "dike," or other interrupting cause, where generally a deposit of gold is found. So simple is the process, yet made wonderfully complex by the recurrence of numerous "elbows," "faults," "horses" and other recurring causes, that its pursuit requires profound study and attention. Whole communities in California are made up mainly of pocket miners, whose aggregate income forms a large part of the whole gold product of the state. All the foregoing is apropos of the fact that prospecting is rife in portions of southern Oregon. Several promising discoveries have been made, the most important being that on the McDonough pocket vein, where several thousand dollars in gold was taken out scarcely a week since, if we may believe newspaper accounts. Even larger discoveries are highly possible, and if prospecting be followed by determined efforts to develop--that is, to examine--the leads, the most flattering results are probable. There is a very large tract of country which deserves to be examined for valuable metals of various sorts, but if the present writer's judgment be not astray, the eastern part of Douglas County presents as good a field as any section of the country for the prospector's craft. Whoever is interested sufficiently in the matter of prospecting is invited to communicate by letter with "Assayer," care of the Oregonian office, whereby information of importance may be obtained. Democratic Times, Jacksonville, May 29, 1885, page 1. Reprinted from the Oregonian, May 21, 1885, page 8 Believing that some of the adult readers of these articles have no more than a general knowledge of the discovery of gold mines in Oregon and California and the progressive steps by which they were developed and made to revolutionize the world, socially, physically and mentally, and that but few of the youthful ones have ever read, or even been told, of the magnitude of these discoveries, the rapidity with which the mining and agricultural districts were settled by people from all parts of our globe, of the suffering endured, the dangers met and overcome, the mode of life of the miners, farmers, traders in the mines and their assistants, the packers, nor of the crudity of the land and the still more crude manner of their application to the varying emergencies of revolving chaos prevailing in the mines from their discovery early in 1848 until the territory of California was admitted into the Union in 1850, it would not be out of place to take a first glimpse of the subject in this article, which would make the subjects treated later on appear in a clearer light. By the 1st of October, 1848, thousands of emigrants, whose original destination was the territory of Oregon, turned their course, when the news of gold discoveries in California met them on their road, towards the latter country to swell the already large population. Hundreds of volunteers had been disbanded in California and had, almost to a man, remained and turned miners. The regular troops deserted from every post in the territory, while the naval vessels lost nearly all their petty officers and seamen. Merchant vessels and whalers entering San Francisco, or any other harbor on the California coast, lost their crews, who often deserted en masse and went to the mines, in many cases leaving behind them back pay and allowances, and if [they were] whalers all their share of the oil, amounting in many cases to several hundred dollars. Vessels from New South Wales brought cargoes of British convicts and turned them loose to mingle with, and affect for the worse, the young American population. These convicts were dubbed "Sydney Ducks," a title too mild for many of them. Officers of the army and navy made excursions to the mines, ostensibly on government business, but really on their own account, to spy out the rich placers and to gather a share of the tempting dust. The following extract from a letter by an army officer to the New Orleans Crescent gives a fair view of the situation: "I expect to have a strange time of it here. Forts without soldiers, ordnance without men enough to guard them, towns without men, a country without government, laws or legislators, and what's more, no one seems disposed to stop and make them." The flood of miners to the original mines on the American River swept on past that place, spreading as it advanced, penetrating all parts of the country and opening up new fields of gold and agriculture as it moved northward. Hon. Thomas O. Larkin, in dispatches to Secretary of State Buchanan, says: "The whole country is now moving to the mines. San Francisco, Sonoma, Santa Cruz and San Jose are emptied of their male population. Every bowl, tray, warming pan and piggin has gone to the mines; everything, in short, that has a scoop in it that will hold water and sand. * * * We have plenty of gold, little to eat, and much less to wear. Our supplies must come from Oregon, Chile and the United States." The Californian of San Francisco says [on July 15, 1848]: "Carpenters and other mechanics have been offered $15 per day, but it has been flatly refused. * * * The rates of transportation for merchandise now charged by wagons are $5 per 100 pounds to the lower mines, a distance of twenty miles, and $10 per 100 pounds to the upper mines, a distance of forty miles." He undoubtedly considered that an extraordinary high rate of transportation, but the writer, and doubtless many who may read this article, know that as high as $75 per 100 pounds has been charged and paid for transportation later than the foregoing date. The Journal of Commerce says: "At present the people are running over the country picking gold out of the ground here and there, just as a thousand hogs let loose in a forest would root up ground nuts. Some get eight or ten ounces per day while none get less than one or two." Again, Mr. Larkin writes: "Some forgo the use of cradle or pan as too tame an occupation, and mounted on horses half wild, dash up the mountain gorges and over the steep hills, picking the gold from the clefts of the rocks with their bowie knives." An ounce of gold usually sold at $16, but at first it sometimes sold as low as $8 or $10, but there was plenty of it, and under such circumstances everybody was happy, careless and often rude, but the rudeness was usually so good-natured that each overlooks it in the other, and fraternity, the best of human ties, bound the miners together in all the varying moods of coquettish fortune. Nicknames were of very common occurrence in the early California and Oregon society, among the high as well as among the low, so careless were the early settlers of their own or anybody else's reserved rights to be called by no other than their lawful names. Any peculiarity of form or feature, or characteristic trait, was sure to bring down upon the doomed subject, male or female, some ridiculous appellation. Yet little or no offense was taken at each other's good-natured failings, for they had all entered the mines for one purpose, and that was to get rich, and held all silly conventionalities in abeyance until that end should have been accomplished. A naval officer, in a letter to a friend at Baltimore, says: "I was invited to dine with a selected party of civilians who were just from the mines, bringing with them long purses filled with nuggets, and an abundance of good nature. Among them was a judge, a seven-footer, who, being called upon for a speech, said: 'Gentlemen, I'm going to give a sentiment, can't make a speech, never could, but even Dr. Leatherbelly here,' slapping another seven-footer on the shoulder, who swallowed a big mouthful and the nickname with something of a wry face 'even Dr. Leatherbelly here, with all his preaching, must acknowledge the truth of my sentiment--that we all came here to make money.' A general roar acknowledged the tall chap a good judge of other men's intentions." The only machine used for a year or so for gathering the gold was a cradle about three feet long and eighteen inches wide. The bottom was usually flat. The back rocker was from two to three inches higher than the forward one, so that the dirt and water would run out at the forward or lower end. The sides were twelve inches high for half their length, when they were sloped suddenly down to a width, at the front end, of three inches. The ends corresponded in height to the sides. On the top, where the sides were of full height, was placed a sieve, made of four boards, one inch thick and four inches wide, nailed together, making an open box or frame 18x16 inches. On the bottom of this frame was stretched a piece of rawhide--sheet iron was subsequently used--which was perforated with holes about three-fourths of an inch in diameter, and usually about two inches apart. On the side of this sieve was fastened a perpendicular handle about one foot long, to be used in rocking the cradle. This sieve was held in place by nailing cleats on the outside top of the cradle, which kept it from slipping off while in use. Under this screen was placed a cloth apron sloping toward the back end of the cradle to within an inch of the bottom. When the machine was in use a man sat down on anything which would answer the purpose, with the cradle in front of him, with the front or lower end to his left. Taking hold of the upright handle with his left hand, he rocked it back and forth, while with some sort of a dipper in the right hand he poured a continuous stream of water upon the dirt or gravel which had been placed in the sieve from some pool or stream of water, on his right hand; the dirt and water in the sieve, moved back and forth by the continuous rocking, until nothing but stones, too large to pass through the holes, remained in the sieve. The water, fine dirt and gold passed through the holes in the sieve, fell upon the apron under it, passed on down the apron towards the right hand or back end of the rocker, under which it passed, turning at the same time at an acute angle to the left, passing on down the bottom of the rocker till intercepted by a cleat at the lower end, which retained a bed of sand into which the gold, as it came on down the bottom, was held--settled under the sand by the steady rocking of the cradle. If the diggings were rich, a half-hour's washing necessitated a cleanup, when the gold and sand were scooped out with a piece of sheet iron, tin plate, spoon or any other suitable instrument and placed in a pan, which was taken to a pool of water and the sand washed out by the miner, who, squatting down at the edge of the water, pan held firmly in his hands before him, sinks the pan and dirt under the water, then raising it to just the surface, at the same time shaking it from side to side, round and round, up and down, giving it all the eccentricities known and unknown to science. Closely watching the gold to prevent its escape, he works and sifts and splashes until nothing remains but the gold, and a plentiful supply of black sand. At night, or when the day's work was over, the pan of black sand and gold was taken to the camp fire and held over it until the sand became perfectly dry. Then he takes a "blower"--a piece of tin five inches wide and eight inches long, with two sides, and one end turn up about one inch high--into which he puts a quantity of gold and sand, then blows, and shakes and puffs until nothing but pure gold remains. The rocker, as the cradle was subsequently called, was good enough at first, but as time brings experience and necessities, it also brought the curious, prying Yankee from the East, who soon improved on the rocker by ciphering out the "long tom," which was used with success for a few years, when it was displaced by the "sluice." A pine tree about twenty-four inches in diameter was cut down, a log ten or fifteen feet long cut off, and one side flattened to a width of sixteen inches; this flat surface was then dug out to a depth of twelve inches from end to end of the log. It was then turned over and the other three sides worked off until a square trough was made, with the sides and bottom about two inches thick. About thirty inches from one end a slanting cut was made, so that the trough had the appearance of two sled runners, held together by the bottom. A screen of rawhide, perforated like that forming the rocker sieve, was nailed tightly over this slanting end, from the extreme points of the runner-shaped sides, back to the remaining bottom of the tom. Thus when the tom was set for use this rawhide screen rose gradually from the bottom of the tom, along under the runners until it reached the top. Under this screen was placed a "riffle box," made of one-inch boards, about four feet long and six inches wider than the tom, the sides and back end of which were six inches high, the sides sloping gradually toward the forward end to a width at the end of two inches. When it was used the whole thing was placed on some logs to keep it above the ground, with the back end six or eight inches higher than the front end. A stream of water would be introduced into the upper end of the tom, and passing on down, would carry dirt and rock down to the screen, where a man stood with a square-pointed shovel, and rubbed and scraped the mass of dirt and stones until all had dropped through the screen into the riffle box below, except the large stones; these he threw out with his shovel. Three men were a full complement at a tom: two to shovel in dirt, one to rub and throw out the dirt. Often a large nugget would be thrown into the tom with a shovel full of dirt, which would soon wash away, leaving the big bright apple of gold to be seized upon by someone and held up in view of the others. "I tell you wha-at, that beats 'em all." "Won't we sleigh ride with the gals when we get back home?" "I'm going to give my gal a gold ring as big as an ox bow, I am." "The Digger Injuns'll git your scalp 'fore you get gold enough to make that ring." "They killed all of that crowd that went up towards the round mountain last week to prospect." "All of them?" "All but old Knock-knees, and he was so durned ugly they wouldn't kill him." "It's possible they wouldn't kill you, either, for the same reason." "We won't quarrel on that score, but I know that you'll be safe if you can get only half a chance." "What kind of a chance does he want?" "A chance to run." All chuckled and worked on. The gals, and the rings, and "Injuns" were for the moment forgotten; the picks sounded heavy and dull as they sank into the yielding ground; the shovels scraped, scraped and the water made music as it rippled down the tom--all are happy; gold in the riffle-box, gold in the tom, gold in the bedrock, gold in the big long purses, hid away somewhere. And so the miners mined, and tramped from creek to creek, from gulch to gulch, prospecting on the flat below, on the hill above, until the hardy wanderers had roamed and prospected on every creek and flat and river from the first discovery to the Oregon line. When new diggings were struck, the news would fly to the nearest camp, recruit, fly on, recruit again fivefold--but the work was done. From every camp within a hundred miles or more pour out a caravan of miners. A few pounds of flour, ditto of bacon, a little coffee or tea, some salt, a few spare shirts, tobacco, pipe and matches, all rolled up in a pair of old blankets or a tattered bed quilt. On the outside of this pack were tied a pick and shovel, frying pan and camp kettle, coffee pot and gold pan, and often, when he possessed such a luxury, an extra pair of old boots or shoes, making a pack often weighing seventy-five pounds. With such a load slung over his shoulder, with gun in hand, the miner climbed the rugged mountains, or crossed the valleys between, as he marched on to the better diggings just a little ahead, sleeping by his little camp fire under the tall pine trees, supping his black coffee from an old oyster can and bathing his soggy beard in bacon grease before taking the delectable morsel between his teeth, disturbed at night by the creeping worm or whisking lizard, a grizzly bear or jaguar, wildcat or panther, or the pelting rain from a lowering sky. Perhaps, too, as he folded his blankets around him at night to recruit his weary limbs in sleep, or at early dawn, as he opened his drowsy eyes, his ears were saluted by an Indian yell, or the whistling of a flight of arrows, embedding themselves in the ground around him, in his blankets, or darting through the quivering flesh of limbs or body. And so fared individual miners in thousands of cases as they tramped from camp to camp, or prospected alone in the wilderness for new diggings for their own. Who was left to tell the fate of that little party of prospectors? See them as they lie wrapped around with scant and soiled bedding, on the low bank of that little creek--feet to feet, and still booted, heads in opposite directions, with their old battered hats drawn over their faces, belts with knives and pistols still attached girt around their bodies, guns lying by their sides ready for use--sleeping calmly "While the sentinel

stars keep their watch in the sky,"

and the tall pine trees, as though to warn the tired sleepers, drop

their dry, discarded slender leaves upon their prostrate forms. Happy

dreams, sent from above, of love, hover around those lowly couches, and

materialize in their slumbers, as"--fond

recollection presents them to view"

their homes beyond the snow-capped mountains. They see their

gray-haired parents, the tenderly loved sisters and the sturdy

brothers, and feel the hearty clasp of their hands as they are welcomed

home again--their wives, too, as their weary footsteps near the open

door, rush out to meet them with cries of delight, and they feel the

pressure of their faithful arms around their necks; they feel the

warmth of their welcome kisses upon their bearded lips. They see their

happy children clustered round them, and the little ones, who now can

lisp their father's name, climb upon their knees, and with clapping

hands, in childish glee, cry out: "Papa's home.""Captain Benjamin Wright," O. W. Olney, Sunday Oregonian, Portland, September 6, 1885, page 2 OREGON GOLD MINES.

Some of the Rich Mineral Deposits of the Faraway States. The Wonderful Machine with Which the Precious Metal Is Extracted from Quartz. An Interesting Account of Hydraulic and Other Processes of Mining. Special

Correspondence of the Leader.

JACKSONVILLE, SOUTHERN OREGON, March 24.--"Southern Oregon" contains three important civil centers. These are Roseburg, near the northern boundary of the region embraced in the above technical term; Ashland, about twelve miles north of the California line; and Jacksonville, the oldest, and, in a historical sense, the most important settlement of the section. Both Roseburg and Ashland have direct railway connection with other parts of the country by means of the Oregon & California Railway. Jacksonville lies to the west of this important thoroughfare a distance of five miles. Ashland is its present southern terminus. There remains to be built of the road, to complete a through line from Portland to Sacramento and San Francisco, one hundred and twenty-five miles. But this portion, being that crossing the Siskiyou Mountains, presents formidable difficulties in the way of construction. A large force is, however, at work upon the track south of this great chain, and in reasonable time it will be completed. It is not difficult to foresee that when done the flood of a new life will be propelled through every artery of business in this wonderful part of Oregon. At present a daily stage, bearing the traveler along a road from which he never loses sight of noble scenery, connects Jacksonville with the railway at the growing town of Medford. Similar to Roseburg and Ashland, Jacksonville is walled around by an amphitheater of stately hills. Shapely buttes pierce the air in every direction. Mount Pitt, a magnificent snow cone of the Cascade Range, looms up fifty miles or so to the east, and yet appears as though rising just beyond the outskirts of the city. Far away northward, peeping over the shoulder of a massive brown mountain, can be discovered a diamond-shaped snow point of exquisite beauty. This is "Diamond Peak," one hundred and forty miles distant. From these kingly summits the snow never parts. For ages it has clothed them and will for ages more. THE

SWIFT ROGUE RIVER,

tortuous,

historical, and in some localities awful in its flow and force, is the

great stream of Jackson County. From its chief tributaries minor creeks

and rivers wander off among the hills and valleys in all directions.Much of the soil of the county, like that of a large portion of the state, is a rich, black alluvium, formed by the continual wearing away of the various kinds of rock and the admixture of vegetable mold. The slopes of the hills and lower mountains, though of a gravelly character, contain nearly every element of fertility. "There exist some extensive tracts wherein deep deposits of warm loam overtop a bed of deep clay." As a whole, the cultivable parts of Jackson County are considered unrivaled for all agricultural purposes. The county embraces about four hundred thousand acres of such land. Crops are a certainty annually. "The cereals have not missed a harvest in thirty-five years," says a gentleman who has resided here longer than that. To fruit culture in the neighborhood of Jacksonville I need not allude, so much have I heretofore written on this and kindred other topics as pertaining to Oregon, but may pass it by, devoting the remainder of this communication to an entirely different subject, namely, that of gold mining, of which industry Jacksonville is the center for Southern Oregon. Viewed in any light we please the subject of gold mining is a most interesting one, on account of the facts and lessons it teaches. For the knowledge I have gained of the industry, as conducted both in Oregon and California, I am greatly indebted to a citizen of Jacksonville, whose familiarity with every phase of mining dates from early boyhood, and also to a gentleman of Ashland possessed of extensive mining intelligence. I have been very grateful to both, for and in preparing this article. That portion of Southern Oregon which is known as the "Mineral Belt" is from sixty to seventy miles long and from twenty-five to fifty miles wide. Its resources are extremely rich and varied, embracing gold, silver, lead, iron, copper, iridium, platinum, cinnabar and several other metals of greater or less value. Numerous new discoveries of gold deposits have been made the past year, more than for some time preceding, and most of them are believed to be rich and worth the working. GOLD

WAS FIRST DISCOVERED

on

the present site of Jacksonville in 1851 by parties passing through

from California to the valley of the Willamette. At that date there was

not a white man living in the territory now known as Southern Oregon. [A few settlers had located land

claims by then, as well as Indian agent A. A. Skinner.]

No sooner, however, was the discovery noised abroad than miners in

large numbers began flocking in from California and elsewhere. And in

an incredibly short time there were scattered among its hills and

gulches between six and seven thousand men, all intently engaged in

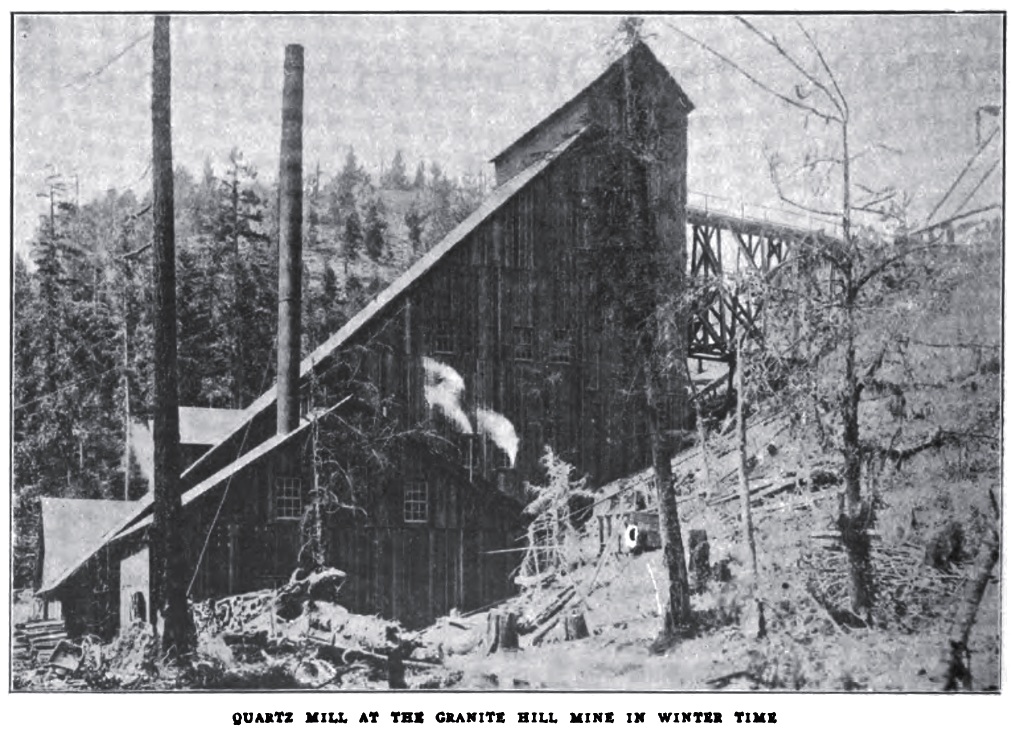

prospecting for the precious metal.From time to time men brought their families on the scene and put up rough frame tents for their shelter. Presently other temporary structures followed for the protection of supplies and stores. Thus Jacksonville sprang into being. In most instances its settlers were a fearless, energetic class of people, possessing very marked characteristics. These, as the production of light placer mines declined, finding themselves surrounded by a country whose soil was as marvelously rich as were its hills and gulches, gradually settled down to other pursuits. To even approximate the amount of gold taken from the mines of Southern Oregon, between the years 1851 and 1865, is said to be an impossibility, for during that period the metal was carried out of the country, not only on mules, in stagecoaches, on pack trains and by express companies, but in large quantities by private individuals. Nothing like an accurate record of the quantity was attempted, nor indeed could be, for the large force of men were not only scattered over a vast extent of country, but surged from point to point as new and fabulous discoveries were reported, or visions of instant fortune rose up before them. It is, however, admitted by all that the amount was very great. Not so was it during the next ten years. After the light placer mines had been worked out and the body of the mining population had drifted to other more tempting gold fields, the steady annual production is estimated to have been not far from half a million dollars. From the close of that period, 1875, down to the present winter, the yield per annum has perhaps not exceeded $100,000. This is due to the light yearly rainfall which has rendered placer mining less practicable. The present winter turns the current again. The supply of water having been abundant, it is believed the production will not fall below $500,000. Just now "quartz mining," encouraged by the aid of greatly improved machinery, is for the first time UNDERGOING

A PRACTICAL TEST

in

Southern Oregon, and gives promise of becoming one of the valuable

industries of the region. The entire mineral belt is almost one

continuous and compact network of quartz leads, and it is well known

that a large percentage of these carry sufficient gold to pay for

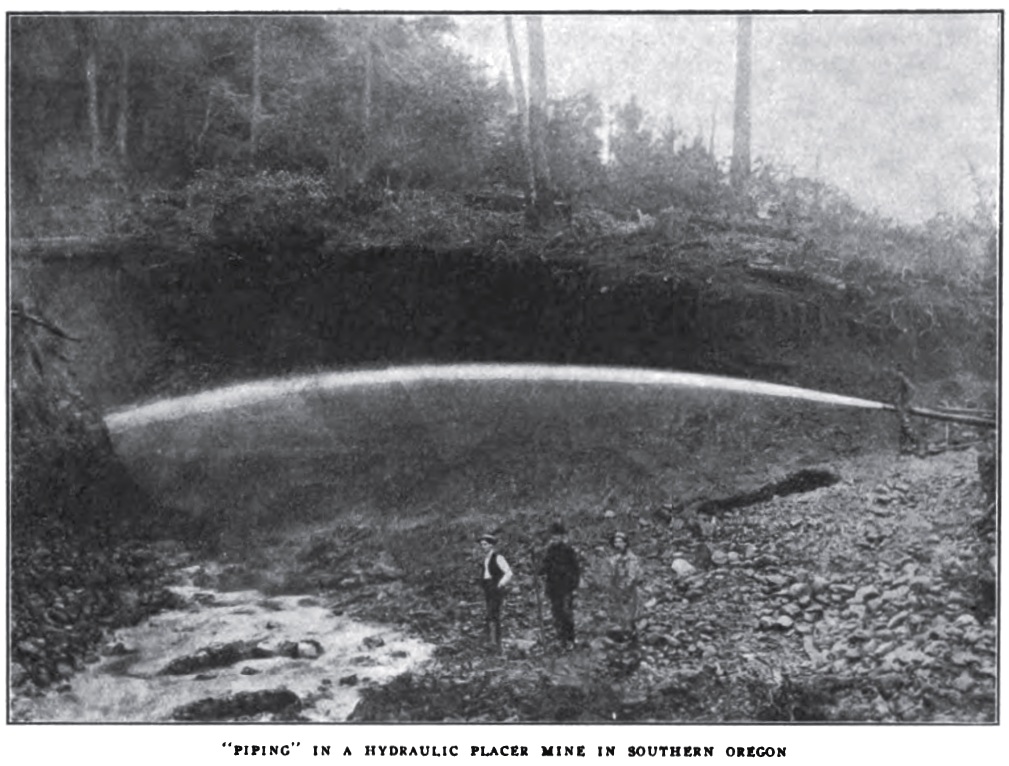

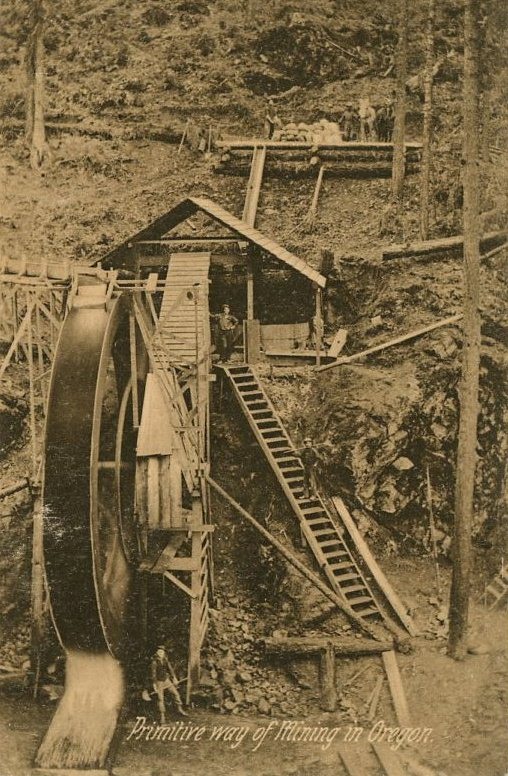

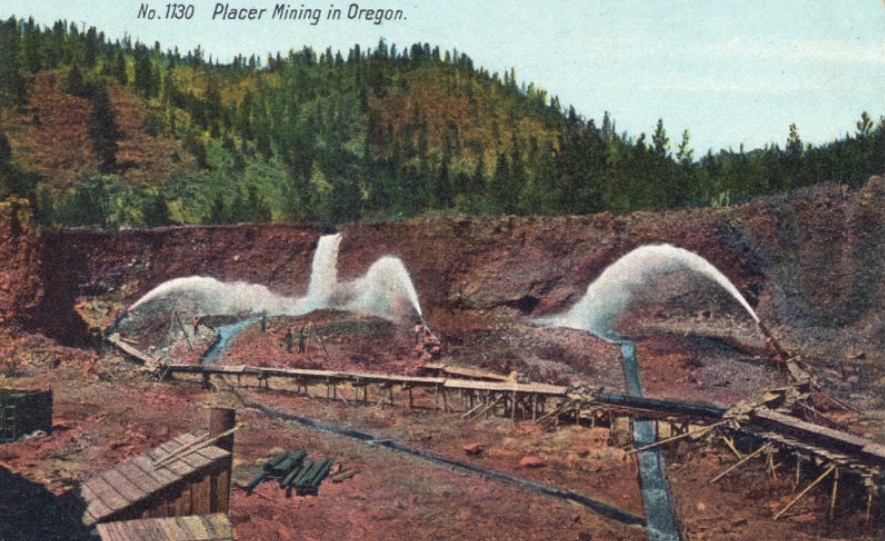

crushing.Many years ago a few of these ledges were prospected with crude machinery, but the trials were made when the gold excitement was at its height, when to secure less than half an ounce daily was considered to be putting forth efforts unworthy [of] a man's thought. Men looked with contempt upon a quartz lead in which they could not discern an abundance of face gold. But today, with marked and welcome improvements in machinery, and increased practical knowledge of quartz mining, it is thought by men who consider themselves good judges that a new and important era in the pursuit is about to dawn upon Southern Oregon, an era rivaling all the past in value to the country generally. A quartz mill, combining all the late improvements, has recently been set up, and is now in successful operation in Jacksonville. It is expected this mill will be a prime factor in introducing the promised new order of things. Among mining men the machine is known as the "Jones' Combined Crusher and Concentrator." Its chief inventor is Mr. E. W. Jones, of Cincinnati, O. The important principle involved in it is this: The handling [of] the ore with the least possible amount of labor, and the bringing [of] every particle of the pulp in contact with the quicksilver, so that not a grain of the gold is lost. Another feature of importance is the small amount of power required to run the very complex and beautiful piece of mechanism, which is that of six horses. The mills with which this class of mining has heretofore been attempted have failed to effect a thorough separation of the treasure from the baser minerals with which it is associated in the leads. In this respect the new invention is a complete success. It execution, also, in crushing the ore is something amazing. Mr. Jones himself is on the ground personally superintending its working. He is a gentleman of pleasing address, and possibly is thirty years of age. Altogether, a quartz mill in operation is a sight well worth seeing, and should the visitor be so fortunate as to be presented with a small gift of the renovated gold, the sight will prove still more interesting. In addition to the placer and quartz mining of Southern Oregon, HYDRAULIC

MINING

is

at present claiming much attention. A number of such mines are in

working order, giving employment to a large force of men, and adding

very materially to the revenue from the gold industry. Very possibly

not all the readers of the Leader

have

had an opportunity of witnessing this impressive method of taking gold

from the earth. For the benefit of such a brief description of the

manner of doing it will be appended, after some preliminary paragraphs.It may be stated in a general way that all mining countries are for the greatest part mountainous, and also that the presence here and there of scoria, trap, basalt, pumice and lava strongly indicates, if it does not conclusively prove, that intense volcanic action has taken place at some time in the past, by which the mountains were heaved up, and the deep, dark canyons were formed. In countries of this character, where the surface has undergone striking changes, new watercourses have made their appearance, flowing their way between mountains and through fair valleys. At the same time there exist ancient or "dead river" channels, which have their way through the mountains without any reference to the present streams. "Indeed," says one of the authorities above referred to, "they generally cut existing rivers at right angles, and as a rule are situated far above them, in some instances thousands of feet." Most of the dead and of the living streams of Southern Oregon contain gold. As the ancient rivers obtained their treasure from the country through which they passed, so, in many cases, have the streams of today obtained their gold by crosscutting these old channels, and they are found to be rich in the precious metals just in proportion to the wealth of the old waterways they have intersected. Into these old-time watercourses the prospector cuts his way with pick and shovel, and with a pan "prospects the dirt" as he proceeds, until satisfied of its richness. These channels and gravel deposits are frequently found high up on the sides of mountains, or on elevated benches of land. They often contain gold from the top down, which increases in amount until the bedrock is reached, and there the best pay is always expected. These deposits vary in depth from ten to one hundred feet, and many of them are much deeper. It was expressly to secure the treasure BURIED

IN THESE DEAD RIVER COURSES

and

gravel bars that the modern hydraulic was intended. In working them a

large amount of earth must necessarily be removed, and to do this

profitably by other than the most improved hydraulic machinery would

perhaps be impossible, since sometimes considerable mountains must be

washed away.We now come to the modus operandi of obtaining the gold. Suppose it is desired to work a bar, or ancient watercourse, fifty or one hundred feet above some river. The instrument by which it must be done is that powerful contrivance known among mining men as the "giant" or hydraulic. Two things then become indispensably necessary. These are an ample supply of water and a sufficient amount of pressure. How are these secured? Sometimes the water is brought from the stream near which the prospector proposes to work. When that is the case, he ascends the stream such a distance as, taking into calculation the fall of the water and the circuitous route it must traverse, will afford him the required pressure. From that point he proceeds to construct a ditch of the capacity necessary for its operations along the mountainside down to opposite the bar or gravel deposit. There he erects a watertight crib, reservoir or receptacle, called a "bulkhead," which is to receive the water from the ditch. At other times, or rather in some instances, the water is brought from a stream thirty or perhaps fifty miles distant. Into the bulkhead the prospector inserts and securely fastens a large sheet-iron pipe two feet or more in diameter, which gradually tapers to a diameter of about fifteen inches, and is of a length sufficient to convey the water from the bulkhead down the mountainside to the giant. Through this it is forced and thrown against the gravel bank from the pressure above almost with the power and speed of a cannonball, but with this decided advantage, that the blow is constant, and therefore resistless. It is now proper to describe the giant, the most powerful of any known mining invention, and yet A

SURPRISINGLY SIMPLE DEVICE.

It

consists of a heavy sheet-iron pipe about ten feet in length, strongly

banded, and tapering gradually from its coupling with the main pipe

bringing the water from the bulkhead down to the nozzle. The size of

the nozzle depends upon the amount of water controlled and the height

of the supply ditch above the mine. The greater the fall of the water

the greater is its power to force a given quantity through a nozzle of

given size. Perhaps the most effective size is one six inches in

diameter.The coupling is a very important part of the giant, or hydraulic, and consists of a combined oval and circular knuckle or joint, having a complete pivotal and circular center, so adjusted as not to leak, and yet so perfect in its action as to be entirely under the control of the piper, who may raise or depress it, or turn it to either side at will. Sometimes there is attached to the nozzle an ingenious little contrivance termed a "deflector." Its purpose is to give direction to the flow of the water without moving the hydraulic. But many miners consider it unsafe, because it turns the powerful stream of water at so short an angle that the piper, unless constantly on his guard, is in danger of letting the instrument get the advantage of him, in which case he is liable to be seriously hurt. The stream of water from the giant is applied at the base of the bank, next [to] the bedrock, thus undermining it and causing it to fall by its own weight. At the same time water is kept flowing upon the top of the bank, whence it percolates downward, softening and adding to the weight of the mass, until finally down it comes, "thousands of tons in amount, and attended with a roar like that of some demon issuing from the realms of Pluto," and dashing a confused mass of earth, rock and trees at the feet of the operator, whose life is thus oftentimes placed at great peril, and is saved only by the closest vigilance, and sometimes by hasty flight. The mass thus laid low is now ready for the ax, sledge and nozzle. Staunch and well-aimed blows from the two former soon dislodge the rocks and trees, while THE

MIGHTY STREAM OF WATER

speedily

dissolves and drives away, through a conduit or canal, styled a

"tailrace," the mass of mingled earth, sand and gravel, with their

accompanying wealth of gold.The "tailrace" is either cut in the solid rock or is made of heavy timber.In the latter case it is called a "flume." It may vary in width from two to eight feet, but must be of ample depth to allow the coarse debris to float away. If built of timber there are placed crosswise in the bottom one, or several, series of iron bars securely fastened. These bars are termed "riffles." Their purpose is to catch the gold, which otherwise would be borne away by the strong current of water now kept flowing through the race. When the race is cut in the bedrock the natural unevenness of the stone secures the same result as the riffles. Furthermore, at convenient points along the conduit, "undercurrents" are constructed to further aid in securing the gold. These are located wherever the descent will admit of their introduction beneath the flume. Here an aperture is cut in the flume over the "undercurrent," and spanned by strong iron bars. "Over these bars the water conducts all the coarser matter, while the finer material, with any gold that may have escaped the upper riffles," drops into the secondary race. Thus but a very small percentage of the treasure eludes the alert miner. Of course great skill is needful in manipulating the water that the baser matter may be carried off not too hastily to give the treasure ample time to find the bottom of the race. This it is not tardy in doing, their own weight soon bearing the particles down unless too small to resist the force of the water. Sometimes, however, the gold is not in "nuggets," but in the form of precious sand. In such case quicksilver comes to the rescue, as it always does in the quartz mill. To this end, a quantity of the cinnabar is placed in a buckskin bag and sifted to and fro in the flume. The metal breaks through the skin in tiny globules, falls down among the worthless gravel and sand, seeks out the gold, forms an amalgam with it, holds it secure until "cleaning up time," when the weeded-out particles are collected and the metals disunited by a process we have not space to describe. After the hydraulic has been at work, say, from three weeks to six months, throwing against the bank of gravel a powerful stream of one thousand or fifteen hundred inches of water, THE

SUPPLY OF THE FLUID

probably

fails. The "dry season" has arrived. Then this branch of the business

ceases until the next "rainy season," and the process known as

"cleaning up" begins. All hands set to work to collect the gold. Some

carefully wash and search the bedrock uncovered. Others cautiously

remove from the race the accumulated rock and gravel. The task may be

accomplished in a few days. It may consume the remainder of the year.

It depends upon the amount of bank washed away. Until the foreign

matter is cleared from the race the water is kept flowing gently

through it from the giant, minus the nozzle. But that done, the water

is partially turned off, the riffles are removed, and the common sand

lightly washed away. The gold is now disclosed to view, is gathered up

with knives and spoons, carefully rinsed, weighed and sent to the mint,

where the government places upon it the "stars and eagle," and sends it

forth to swell the circulating medium of the country.It would be well if the making of gold eagles plentiful were the only result of hydraulic pressure. A more bitter fruit is the overspreading of fertile plains, valleys and hillsides with the destructive debris which the giant produces in vast quantities. In Southern Oregon the devastation has as yet proceeded to no great extent. But in California, where hydraulic mining continued for years, some of the fairest portions of the state were actually desolated by thick deposits of broken rock and gravel that were conveyed to them from the mines. So long as the mining interests of the state were regarded as paramount to those of agriculture the havoc went on. But when mining suffered some decline, and as a consequence agriculture assumed more importance, it was discovered that the covering up of land so valuable would prove an irreparable loss. The farming community, therefore, became aroused, and exercising superior wisdom, pluck and forethought, went to work and secured a perpetual injunction against that class of mining, in any locality where waste of productive lands could follow. Wholly aside from its mineral resources a mining country contains valuable sources of information. Its topographical and geographical features embrace topics of unusual interest. A chapter on facts and theories connected with these subjects may someday follow this article. Emma

H. Adams.

Cleveland Leader, April

12, 1886, page 3GOLD MINING IN SOUTHERN OREGON.

While in Western Oregon gold has been found in profitable measure all

the way from the California line to the Santiam River, mining has so

far attained its greatest development in Josephine, Jackson and Douglas

counties. From these three counties the gold output for the year 1899

is computed at about $2,400,000.Yet the industry may be said to be only in its first stage. There has been a scratching of the surface in spots, but the deep work is, so far, comparatively limited, and far less than would be justified by legitimate exploitation of the leads which have been uncovered. For this tardy development, some explanation is found in the early history of the section. Many millions in gold were taken from Southern Oregon in the fifties; but the adventurer of those pioneer days sought only quick returns with no expenditure. To him mining was neither art nor science, and grim necessity kept him moving strictly along the lines of least resistance. His labors were confined to creek beds, low bars and such free-milling ledges as were found easy of access. He was no stayer, and was easily stampeded away by the later discoveries on the Fraser River, in British Columbia, and the Salmon River, in Idaho. The abandoned claims were then raked clean with the Chinese fine-tooth comb; gold mining relapsed, and the industry long remained as dormant as though the pioneer had left it untouched. Unfortunately, also, in the upheaval and erosion of the great mountains of Southern Oregon, pockets and chimneys were detached from the main bodies of ore. These coming in the path of the carpet-bag prospector were essayed with great gusto, and served to attract only a more worthless class of gamblers, who, lacking the experience and grit of the true miner, and failing to find a nugget under every wayside bush, cursed the country and passed on. This unmerited fame led practical investors to list Oregon claims among the extra hazardous ventures. Moreover, the public has been loath to believe that valuable mines could exist in a region so accessible, so fertile, so climate-favored, as is this same Southern Oregon. But for these very reasons does Southern Oregon today offer a most inviting field to either prospector or investor. Enough has been accomplished to dissipate past error and misconception, and the present returns are quite ample to indicate the direction and value of the mining industry when prosecuted under correct methods. And here exists, if anywhere, the poor man's chance. Given experience and perseverance, his capital need not be extensive, and he can pretty nearly step off the Shasta train and go to work. Good water and fuel is in plenty, fish and game for the taking; heat will not enervate, cold benumb or snow impede. Flour and bacon, health, plenty and civilization are not left behind. For several years placer mining, in Josephine and Jackson counties, has been prosecuted with vigor and capital, yielding rich returns, but it is only of recent date that quartz has received much meed of attention, and that there has been more than a desultory overturning of the surface. Since tunnels and shafts have been pierced to the granite and slate, the results have surprised the talent, and now quartz developments have assumed such magnitude in several widely separated districts, from Bohemia to the Siskiyous, as to attract the pronounced interest of investors from all sections of the country. J. B. Kirkland.