|

|

Kirchhoff Does Oregon, 1871 In late September 1871 Theodor Kirchhoff traveled from Portland to San Francisco by train and stagecoach--apparently for no other reason than to write about it. The southern Oregon portion of his account, published in the German magazine Globus in 1872, is translated below. He revised and updated his account in 1875; that translation is transcribed at the bottom of this page. Forays into Oregon and California (1871).

By Theodor Kirchhoff V.

When

we left

Oakland after ingesting a by no means luxurious dinner and

drove to the

town of Roseburg,

I formed a permanent memory of

the Umpqua

mud.

The black soil had

become so greasy and sticky

after the last rain that it completely

filled the openings between

the spokes of the wagon wheels.

Every few hundred yards we

had to stop, because the six

horses

which formed the team could pull the stage no farther forward,

and clean the wheels

with fence rails,

a very tedious work, from which only the blind

music teacher was exempted by

the driver. In Western states in the

Americas it is not uncommon

when a traveler has paid

his good money to ride in

the stage to

have to walk halfway beside the crowded coach

on foot, otherwise

the horses would not be able to get

out of the place. Since I had paid

the stage company 50 dollars

in gold for a place in

the coach, such work was doubly

hard.The countryside continued to be beautiful, and seeing the same from the train or on a good road, rather than go through the Umpqua mud, would have been a capital pleasure. The small, green valleys, enclosed by wooded hills, which provided a new prospect every few miles, mostly made homes for only one farmer's family, and it was a rarity to see two or more houses in a valley. A farmer in Umpqua buys all the land in one of these little valleys from the government and then has the nearby wooded hills as excellent grazing ground for nothing, because the valley alone can find a buyer. He who, after the railroad has connected this country to the outside world, has such a little paradise as his property, is in fact a lucky person among the farmers of America! Theodor Kirchhoff, "Streifzüge in Oregon und Californien (1871)," Globus, Vol. XXII, No. 8, August 1872, page 123. Translated from the German. VI.

After

crossing the North Umpqua

by ferry,

which joins

the southern branch of the river below Roseburg, we passed the town of

Winchester and

finally arrived at about five clock in the

evening at the town of Roseburg

, the capital

of the Umpqua

,

lying in an idyllic

setting

75 miles from Eugene

City,

in which place I

stayed until the next evening.

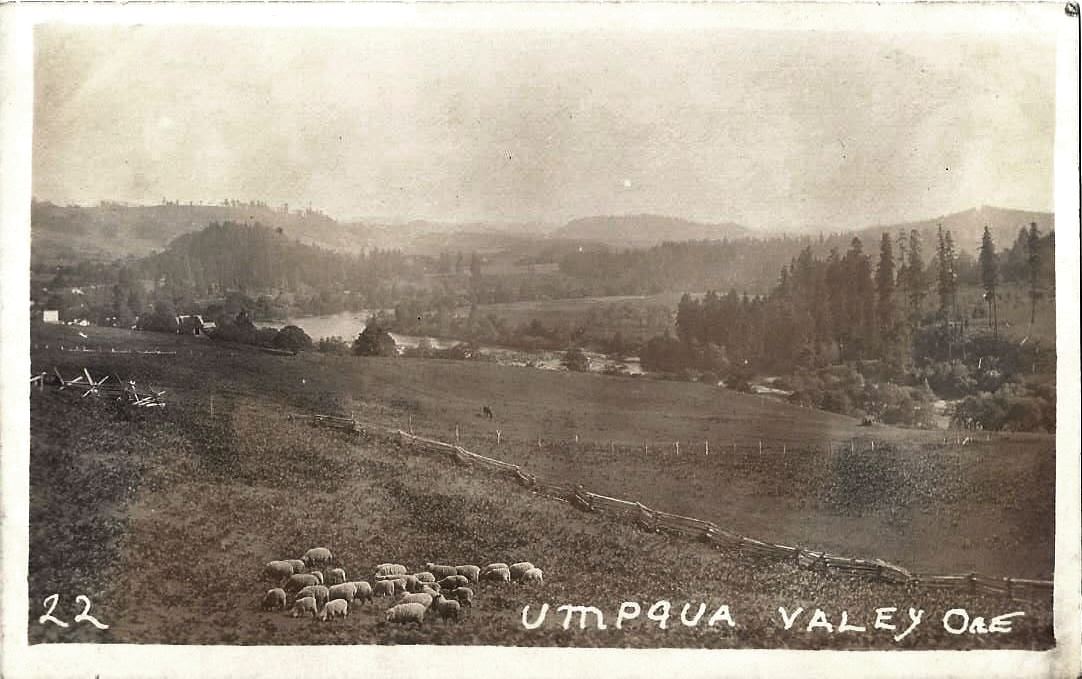

Roseburg, a friendly little town of about 500 inhabitants on the South Umpqua, pleased me very well. The unpaved streets were, however, due to the recent rains, in a deplorable condition; but the environment of the place was lovely, the green fields and gently swelling hills, the myrtle, oak and acacia trees. The city is the seat of government of Douglas County, which has an area of 5000 square miles. The sparse population of the area comes here for goods and wares of all kinds, and Roseburg merchants have in their hands the whole business of exporting products of the surrounding country. 800,000 pounds of wool, 400,000 pounds of bacon and about 4000 head of beef cattle are exported annually from Roseburg. The grain harvested in the county is consumed domestically. Sheep farming is important in this region and a major source of wealth for the population. Douglas County produces more wool than any other three counties in Oregon put together You meet few Germans in the Umpqua country, apart from some Jewish merchants and brewers, and these few are sadly Americanized. I talked in German to a German innkeeper in Roseburg in the presence of several Americans. The good man went quite red with shame when I exposed him so thoughtlessly to the Americans as a Dutchman. He answered me in English that he had long since forgotten his German. Roseburg is certainly one of the healthiest places in the world. A doctor who wanted to live on the fees paid by his patients would have to die miserably of hunger. In this area nobody is ever sick, and people all look as if any of them should live for a century. On average, one expects one death per year for each 500 inhabitants. The last fatality in Roseburg, as I was told, was in the spring of 1870. Of course, Roseburg has their local newspaper, but intellectual food seems to be not particularly relished by the sturdy population. Only a weekly newspaper, The Plaindealer, ekes out a precarious existence on the Umpqua. The editor of a second local newspaper, The Ensign, almost died of hunger a year and a half before my visit because the Roseburg people did not subscribe. He therefore came to the reasonable decision to be a sheep breeder, and now manages the wool shears instead of scissors. As might be expected, I found the citizens of the remote community in great excitement over the approach of the railroad, which was all the talk of the Umpqua. Of Mr. Holladay, who wanted to have sixty acres of valuable land donated near Roseburg in order to create a station, there was outrage because of his presumption. The railroad must come to Roseburg, they said; Roseburg would not be frightened by any millionaire! They would not--God forbid!--But here, as in all small Oregon towns, reason will prevail and they will be glad, finally, when Mr. Holladay accepts the gift by grace, rather than build his railroad many miles away from the city and create a new opposition town.  The Umpqua Valley circa 1910. On the evening of the 28th of September rainy weather delayed the departure of my stage until half past ten o'clock, six hours later than usual, to get through the Umpqua mud. Into a bright moonlit night we went out onto the high bank of the Umpqua. The broad river snaked silvery deep below us in the valley, whose otherworldly terrain rose to park-like wooded heights. But soon we were in a dark mountain. Over the next 13 miles led a terrible rough road through a canyon of the Rogue River. Dark forests covered the slopes of the mountain on both sides. In the forest a panther on the prowl screamed several times quite close to us, its peculiar sound like a crying child, so that the horses, smelling the beast of prey, could hardly be restrained, tossing the stage about as if to break it to pieces. At last we passed the small town of Canyonville [Kirchhoff is mistaken--Canyonville is at the north end of the Umpqua Canyon] and left the gloomy defile and drove in more open area about the Burnt Hills and Grave Creek Hills, which low mountain ranges form the watershed between the valleys of the Umpqua and the Rogue rivers. The Rogue River Mountains are a more difficult terrain for the railroad than the Calapooias, and although its elevation is not significant, it must make deep cuts, and trestles up to one hundred feet high will be built. The line of the railway leaves the Umpqua River 2½ miles from Canyonville and runs to the south through Cow Creek Pass. At dawn we were at the Levens stage station [Galesville], 40 miles from Roseburg, in the headwaters of Rogue River [the headwaters is actually on the slopes of Mount Mazama], which discharges into the ocean 15 miles [it's actually more than 30 miles] north of the border of California. The scenery had changed considerably. The forest was lusher than in the Umpqua Valley, but the thin, reddish clay soil appeared unsuitable for agriculture. I rarely saw farms, and those I saw were sorely neglected. Fences were dilapidated and had apparently been broken for years; it was clearly evident that the farmers considered it a waste of effort to use money and manpower to improve their properties. Fruit, which grows inexhaustibly in the northern districts of Oregon and is available at ridiculous prices, was a rarity here. Although we passengers looked for fruit trees around the humble homes sparsely located along the road, our scrutiny was almost entirely unrewarded. At a trot the stage went downhill now, over hill and dale and the infamous corduroy roads; it was enough to shake our bones loose from each other. The blind music professor and the life insurance agent, my friend the civil engineer, the lightning arithmetician [Col. Robert Cromer], the red-haired Irishman, and I implored the driver to slow down. But he laughed at us and whipped the horses, cursing the Umpqua mud that had wasted his time and put him off schedule. Beside us Cow Creek roared through the forest, as if to make fun of our suffering. We several times crossed the winding creek over the most uncivilized bridges under the sun--loose sticks laid on round cross bars side by side--driving rapidly over them they rattled and jumped high in the air, and the old gnarled oaks stretched their moss-draped branches sometimes teasingly into the car window, or rattling on the coach roof, as if delighting in our passage. We breathed easier when the log roads were behind us and we reached a smooth road in an open area. At the first stopping place I took my seat on the box beside the driver to enjoy a better look around than was possible from the interior of the coach. Narrow spruce-lined mountain ranges now followed each other in ever-changing contours and slid like a succession of dioramas past the eye. The weather, as the sun rose higher, became glorious, and a deep blue sky, clear and unclouded, arched over the romantic landscape. At the top of a rocky ridge, the driver brought my attention to an isolated, rounded boulder lying on the left near the road and told me the Umpqua Indians used to make pilgrimages to worship it. He stopped the coach for a while, and I got down for a closer inspection of the sacred stone, but noted neither incised characters nor any other thing extraordinary about it. Whether the Indians worship a deity in the rock, or whatever else was the case, I could not find out. The road now led through a forest, choked with half-burned fallen logs wildly covering the ground--the traces of a devastating forest fire. On the hills grew numerous manzanita bushes, whose gnarled and hard dark-brown wood is carved into pipe bowls and forms an export item. We met a wagon that was loaded down with this wood. At Grants Pass, 65 miles from Roseburg, a wonderful view surprised us as we entered the valley of the Rogue River. Spread in front of us to the south were the powerful dark purple mountains of the Applegate and Siskiyou mountains, the latter just 20 miles north of the border between Oregon and California, while the hilly country in between was mottled with different shades of color of the scattered deciduous and coniferous forests. From time to time we passed abandoned gold placers, peculiar deserted messes of trenches, holes, wooden flumes, turned earth, piles of washed-out loose stones, crumbling huts, etc. Soon we reached the Rogue River and traveled several miles along its rocky shore. The foaming, swirling flood of the wild mountain stream roared along magnificently wooded mountains rose up from its opposite shore. In the river miners were working diligently in the gold placers. Half a dozen large and small waterwheels, their broad blades turned by the raging flood, pumped water up to the sluice boxes, to which the Chinese miners carted the gold-bearing earth and shoveled the same into them--a colorful and lively picture! For a time now we left the Rogue River and crossed one of its tributaries, the flat and wide Evans Creek. The forest and mountain scenery here was very impressive, reminiscent of the world-famous scenery of the Sierra Nevada. The lighting of the mountains by the rays of the setting sun, which lengthened the shadows of the tall pines on the green slopes, contributed not a little to make this a painterly landscape of captivating beauty. Only the frequent abandoned mining camps tarnished this beautiful country with their reminders of a harsh civilization. An old dilapidated stockade erected by the roadside, built of huge upright tree trunks standing close together, recalled the bloody wars of the 'Fifties which raged between the Indians of Southern Oregon and the whites. Only when the Indians had realized the impossibility of further resistance to the thousands of gold-fevered whites did they bury their tomahawks and become the most peaceful creatures on God's earth. But their old warrior pride is all gone, and one encountering in this country a company of redskins in their beggar's rags can hardly imagine that these pitiful figures are the descendants of the warlike Umpqua and Pitt River Indians who fought the whites with desperate valor for many years every inch of ground. Once more we reached the rocky banks of the Rogue, the clear rushing waters ranging in width from 50 to 200 yards, and I noticed several large wheels of gold placers, which slowly turned in the fast-flowing waters. Well-ordered farms and neat houses were on both banks of the river, and the corn stood in the fields with full golden-yellow ears---sure evidence that we were rapidly approaching a civilized area. In the friendly hamlet of Rock Point, 13 miles from Jacksonville, we crossed the Rogue River on a high and long wooden bridge. The name of the place referred to its location. The bed of the river was here strewn with black rocks, which piled up at a promontory at one point on the shore. The bridge was less than ideal. A wagon driver in Germany would hardly trust himself and his team such a miserable structure over such a raging torrent as the Rogue River, staring at the rocky riverbed below. But in Oregon security is not as great a concern. Our driver cracked his whip and cheerfully drove his chariot and heavy wagon over the high bridge, which creaked and cracked and swayed in a highly dubious manner.  From

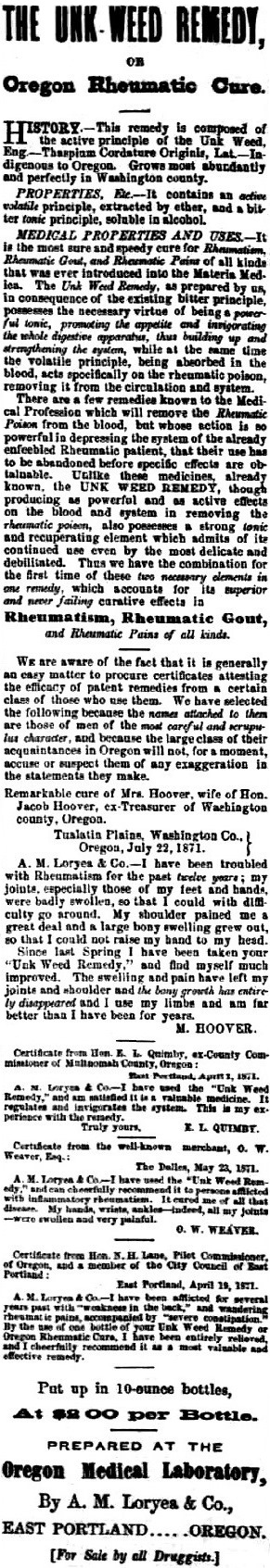

the bridge we saw the Rogue River Valley in perspective as a long

vista down the middle of the wild roaring river, with its black basalt

banks and magnificent forested mountains on both sides, and the white

buildings of Rock

Point lovely on the nearby shore--a highly romantic view. On

the railing of the bridge I read, perhaps for the thousandth time,

large white painted letters touting a patent-fever

medicine--"Unk Weed Remedy!"--I say for the

thousandth time, because since I left Portland these words seemed to

follow me

at each fence, every large tree, on any prominent rock, on swine pens,

houses, etc., everywhere were painted the same words to attract

the attention of travelers. "Buy it!--Buy it!--Unk Weed Remedy!--Oregon

Rheumatic Cure!''--These

signs, which extend as far as San

Diego, must have cost the medicine manufacturer a sizable amount, but

in America nothing is more rewarding than humbug!

From

the bridge we saw the Rogue River Valley in perspective as a long

vista down the middle of the wild roaring river, with its black basalt

banks and magnificent forested mountains on both sides, and the white

buildings of Rock

Point lovely on the nearby shore--a highly romantic view. On

the railing of the bridge I read, perhaps for the thousandth time,

large white painted letters touting a patent-fever

medicine--"Unk Weed Remedy!"--I say for the

thousandth time, because since I left Portland these words seemed to

follow me

at each fence, every large tree, on any prominent rock, on swine pens,

houses, etc., everywhere were painted the same words to attract

the attention of travelers. "Buy it!--Buy it!--Unk Weed Remedy!--Oregon

Rheumatic Cure!''--These

signs, which extend as far as San

Diego, must have cost the medicine manufacturer a sizable amount, but

in America nothing is more rewarding than humbug!A few miles further on we leave the canyon of the Rogue River, and the valley of Jacksonville opens before our view with its trees, fields and farms on the fertile plain. The eye wanders for miles about a magnificent countryside to the densely forested Siskiyou mountain range, at the foot of which lies the city of Jacksonville, the main town in southern Oregon. A little to the left and before us stands the massive 11,000-foot-high snow-covered peak of Mount McLoughlin, a neighbor of Klamath Lake 90 miles distant, reaching high into the blue-ringed ether and looks down with its silver head like a king with a cloud diadem on the green valley below. We quickly hurtle down the plain, and soon the Rogue River Mountains are far behind us. The scattered groves of wide-branched native oaks are reminiscent of nearby California, and the landscape has nothing in common with Oregon. In a delightful ride on smooth roads between well-cultivated fields and fruit-laden orchards and past inviting houses, as we approach Jacksonville we pass extensive gold placers, unworked in this season, and finally, at five o'clock in the evening, the streets of the city await, after an uninterrupted stage journey of 95 miles since I left the Umpqua last night at Roseburg. Theodor Kirchhoff, "Streifzüge in Oregon und Californien (1871)," Globus, Vol. XXII, No. 9, September 1872, pages 136-138. Translated from the German. For more on Unk Weed signs, see the Democratic Times, August 5, 1871, page 3 VII.

The

city of Jacksonville, which lies on Jackson Creek, a tributary of

the Rogue River, 293 miles from Portland and about 130 miles away

from the sea coast, counts around 1500 inhabitants and is the main town

in southern Oregon. The

population of this place is very mixed. Chinese

are an unusually strong presence, and almost a third of the population

consists of Germans. Irishmen,

Portuguese and Kanakas (Sandwich Islanders), the latter valued as hard

workers

in the gold mines, form major segments of the population.Jacksonville owes its origin to the discovery of rich gold deposits in southern Oregon in the year 1850. At the time of its flowering this area rivaled with the Yreka mining district in California, beyond the Siskiyou Mountains, and even still the product of its mines is significant. The place looks nothing like a mining town, where the population tends to be in a fever of excitement, but rather has the air of an ordinary, quiet American town. The lively entrepreneurial spirit of the California mining town seems to have been lost in this sleepy Oregon mine district. They complained a lot about the drought of recent years, whereby the yield of the still very rich placers has decreased from $300,000 in gold to about 35,000 dollars. However, the lack of water could be easily overcome by the creation of a large mining ditch about 92 miles long. One such plan that requires the comparatively low capital investment of only 75,000 dollars would be easy to implement and bring enormous benefits. In a California mining town such a ditch would have long since been created, but in Jacksonville the motto is--and the big ditch has here been on paper for ten years--"always go slow." The area of Jacksonville is not only rich in placer deposits of granular free gold, but also in gold- and silver-bearing quartz, and by the latest operating methods of mining, carried out in an energetic way, processing of these ores yields amazing results. In the quartz mines at Gold Hill, 7 miles north of Jacksonville, was found the richest gold ore on this coast. From a pocket of only 12 cubic feet $130,000 worth of gold was gathered. A small pile of collected pieces of metal-bearing quartz held 7000 dollars in silver. Silver ore, scattered in pieces from the size of a walnut up to 25 pounds of weight and of great wealth, are all over the area. But the yield of the gold-and silver-bearing quartz veins (ledges) is realized here in a very primitive way. The two most important of the Gold Hill mine shafts have a depth of only 150 and 80 feet, and no other in the whole neighborhood is deeper than 14 feet. The quartz amalgamation stamp mills are poorly constructed, furnaces are not available and the mines are handled very carelessly. An energetic Californian population would increase tenfold the yield of the mines in southern Oregon. Jacksonville is not merely an important mining town of importance, one of the most fertile valleys of Oregon is located in its immediate vicinity, making it the natural trading place for the Rogue River Valley with a width of 15 miles from north to south and a length of 50 miles of east to west. Wheat, oats and barley, as well as apples, pears, plums, apricots and all kinds of berries (gooseberries, raspberries, etc.) and garden produce thrive admirably. Handsome, well-cultivated farms are numerous in this valley. A brisk trade takes place with Fort Klamath, 90 miles away, where some companies of United States military are in garrison, securing all their food needs here. Outside commodities for the most part must come 120 miles to remote Jacksonville from the seaport of Crescent City, but there will soon be a radical turnaround in all trading conditions with the continued construction of the railway, which will bring the cost point of commodity transport significantly lower. [The railroad didn't reach the Rogue Valley until 1884.] Currently freighters calculate the steamboats from San Francisco to Crescent City at 5-6 dollars per ton, another 2½ dollars per ton port charges, and transport from the landings to Jacksonville an additional three cents per pound. I may mention that the session of the Oregon State Legislature in the city of Salem officially changed the name of Rogue River to the more civilized-sounding Gold River. But the residents of Southern Oregon consider the old name more appropriate, and it has become to them a reminder of the pioneer days. The new name is not recognized here, and as a "rogue" river it flows through the wild mountains to the ocean as before. On evenings during my stay in Jacksonville my traveling companion, the lightning calculator, gave the whole population of "the intelligent people of Jacksonville" a lecture on the street by torchlight on a simplified method of arithmetic. With chalk he reckoned on a blackboard the most complicated tasks fabulously quickly; adding a mile-long column of large numbers in a jiffy, multiplying trillions and quadtrillions so that it looked like a work of art, struck his head and pulled out answers as if with a corkscrew, made lightning calculations such as I had never seen and accompanied it with incredible patter, told anecdotes, etc., so that the "intelligent people of Jacksonville" stared open-mouthed and cheered delightedly at his jokes. Finally, he sold his arithmetic books that contained all his secrets--a brochure of 144 pages, three dollars the copy--as fast as hotcakes. In every little place in Oregon I had watched the same amusing spectacle during the last week, but in Jacksonville the "Yankee lightning calculator" exceeded himself. His lectures are a highlight of my memories of this trip! On the morning of October 1 [1871], in glorious weather I began the next stage of my journey, the goal being the mining town of Yreka, California, 62 miles distant from Jacksonville. Through a well-cultivated area, in which the fields were covered with picturesquely scattered oaks, we had a pleasant drive on a good road to the wooded part of the Siskiyou Mountains. The name Siskiyou is an Indian word meaning "horse with a short tail." The outer shape of the mountain is thought to be similar to such a horse, hence the name. To me it was not possible to see the vague resemblance which the vivid imagination of the redskin had concocted. [The reference is to a favorite saddle horse that died in 1829 on one of Alexander McLeod's trapping expeditions, not to the appearance of the mountains.] Fifteen miles from Jacksonville we passed to our right hot sulfur spring and bath house and soon reached Ashland, the southernmost town of Oregon, lying in a pleasant environment in the foothills of the Siskiyou Mountains. In Ashland I noticed the handsome mill of a woolen factory and a stonecutter's, and the place had a nice appearance. Here left us, to my delight, the argumentative blind music professor; a member of the Oregon Legislature, who traveled with us to Yreka, took his place. Unfortunately, the exchange was not as pleasant as I expected, because this Oregon statesman [Henry W. Corbett] by his crude manners soon made his presence completely intolerable. He revealed in the course of conversation, among others, the quaint view that children under the age of 14 should not be sent to school; it was far better, he said, that they run wild until then to develop their bodies, as opposed to sitting at a desk, where, as is known, only stupidity and profligacy are learned! Most of his colleagues in Salem, he added, had the same view as he did, and he hoped that the state of Oregon would soon adopt these healthy principles into an appropriate education law. He started school only after his fifteenth year, and yet learned enough to bring him into the House of Representatives of his enlightened state. Against such arguments, of course, we could not argue, and we fellow travelers shrank ashamed from that Oregon Solon. After we had taken our lunch at the "mountain view" stage station [presumably Barron's Mountain House], where in front of the inn across the way was attached a large sign with the misspelled words "tole road" instead of "toll road" (evoking uncharitable thoughts about the enlightened state of Oregon), we changed to a team of six horses for the mountains. The narrow road wound gradually up between slopes lined with magnificent conifers. Having reached the summit, we had a magnificent distant view of densely wooded blue mountain ranges over which to our left the snow-covered mass of 14,440-foot-high Mount Shasta (also called "Shasta Butte") rose before us--a gorgeous image! Now the stage went rapidly downhill on winding roads. Each new view of the mountain, one more beautiful than the other, delighted the eye. Here, where bright green meadows nestled between the dark fir woods, there roared a foaming brook, whose banks were charmingly framed with maple and cottonwood, white-trunked birches and a golden bower of swamp ash, while the dark purple mountain ranges lay picturesquely in the distance, and old Shasta Butte raised his silver dome high in the blue ether. At Cole's Station, 35 miles from Jacksonville, the main chain of the Siskiyou Mountains was behind us. The friendly station building with the long white picket fence spoke of summer, the air was warm and the southern landscape with the brown hills had a true Californian appearance. About 400 yards beyond Cole's Station we found the southern boundary of the state of Oregon, which has been placed at 42 degrees north latitude. On a dusty road we passed abandoned placers and crossed wide, parched riverbeds, filled in winter by roaring waters, until after a journey of 8 miles we reached the mining town of Cottonwood. After the winter rains fall the town leads a busy life, but this time of year it is vacant. The all-invigorating water is indispensable to work the mines, and the placers are very desolate there. Two and a half miles beyond Cottonwood we found the Klamath River, a rushing stream with rocky, barren shores, which we crossed by means of a ferry. The river is the natural outflow of the small and the large Klamath lakes--35 and 60 miles to the north-northeast from here--and pours westward into the ocean. On the northwest shore of the great Klamath Lake rises the 11,000-foot-high Mount McLoughlin (also called "Mount Pitt"), which I had first seen from the valley of the Rogue River but, covered by intervening heights, cannot be seen from here. Klamath River has very treacherous waters, full of eddies and rapids, which has dealt a violent death to many a daring swimmer. The ferry on the river, which is on the main road between Oregon and California, is a lucrative monopoly; ferrying a cart and two horses costs 2½ dollars. When the gold mines were first discovered in southern Oregon and miners, merchants and adventurers from California by the thousands flocked there, this ferry was a real gold mine and its owner must have averaged 300 dollars per day. Theodor Kirchhoff, "Streifzüge in Oregon und Californien (1871)," Globus, Vol. XXII, No. 12, December 1872, page 184. Translated from the German with the assistance of Google Translate and occasional reference to Frederic Trautmann's Oregon East, Oregon West, Oregon Historical Society Press, 1987, an English translation of a later edition of Kirchhoff's Oregon essays which amends and abridges the original. The text below recapitulates the material above. It was published by Frederic Trautmann in his Oregon East, Oregon West: Travels and Memoirs of Theodor Kirchhoff 1863-1872, an English edition of Kirchhoff's 1875 Reisebilder und Skizzen aus Amerika (Stories and Sketches of Travel in America). Kirchhoff's book, updates the magazine articles above to 1875, abridges the 1872 articles and adds material from his notes or memory. TO ASHLAND AND YREKA BY STAGECOACH

I took my seat at 1:00 on September 27 [1871]. The night would have

been moonlit but for black, stormy weather. Clouds chased each other

wildly across the sky. Now they obscured the moon and dumped rain that

pattered on the stagecoach, and now the moon's dim light weakly

illuminated the forested landscape. Gusts of wind whistled about us.

Five other passengers and I were bounced and jolted by the rough road.

Sleep was impossible. I rejoiced with daybreak and at least the chance

to look around, a relief from the strain of travel. We were just

entering the thickly wooded Calapooia Mountains, which run east-west

and divide the valleys of the Umpqua and the Willamette. These

mountains are 2,000 feet high, but a gap opens here, Pass Creek Canyon,

only 300 feet above sea level.

My companions were an interesting group. The life insurance agent spoke only of premiums, dividends and mortality rates. The blind music teacher, an argumentative, waspish artist, claimed he gave singing lessons to Oregon ladies and could play any instrument from the jew's harp to the Steinway grand. The civil engineer, employed by the state of Oregon, told me many worthwhile things about the countryside. The Yankee master arithmetician lectured to dear Webfeet in small towns, calling himself the lightning calculator, and in his head performed the most difficult computations with incredible speed. The hog dealer from Chicago, a red-haired Irishman inspecting Oregon's porcine resources, said he felt good only when he heard the squeal of pigs being stuck and could wade ankle-deep in the blood of a slaughterhouse. Talk never stopped in such a group, take my word for it! Crossing the mountains, we enjoyed an interesting diversion in the many camps of shacks and tents pitched by railroad workers, often in surprisingly beautiful places. Here Chinese and there whites shouted a cheery "Good morning!" to us as they boiled coffee or made morning toilets, standing in groups around tents and shacks. The railroad pays whites $60 a month and found. Of that salary, $35 a month can easily be saved. John Chinaman, however, whose needs are less, has to be satisfied with a monthly $30. Frequently I saw big signs on trees near the road: Railroad hands wanted or One thousand laborers wanted. No trouble building a railroad here. Follow Nature's way through the mountains and let adjacent forests provide inexhaustible wood for ties, bridges, etc. Three and a half miles of corduroy [road], of the most primitive construction, nearly did us in. Then, following Pass Creek, we left the canyon for open country: the romantic Umpqua Valley. We breakfasted at the Hawley stage station. A unique meal. Our hosts, two Irish bachelors in unkempt clothes, shuffled about sockless in tattered slippers. The cook was Chinese. Filth prevailed in this hole that presumed to be a hotel, and the food corresponded to the establishment and personnel. Was I happy when the driver cracked his whip to signal departure and I could escape this "hotel," hoping never to return! The rain had stopped. A splendid landscape lay before us in bright sunshine. Level, grassy meadows, hilly tracts and picturesque forests alternated. Coniferous and deciduous trees asserted all the colors of autumn. Every glance to either side took in a different hollow or another basin ringed by green hills. Sometimes farms nestled there idyllically in quiet seclusion. The forests have for the most part little undergrowth--Indians usually burn it in summer, to facilitate hunting--and the forests therefore look like parks. The soil, black and loamy, is supposed to be extraordinarily fertile. Wool and bacon are the valley's chief exports. Wheat is usually fed to hogs; the cost of transportation prohibits shipping it from this remote spot. Schooners and steamboats can navigate the main artery, the Umpqua River, only as far as the little town of Scottsburg, thirty miles from the mouth. Rocks that impede shipping are to be blasted out at federal expense but, since a sandbar will remain a peril at the mouth, the river can never be important for transportation. Obviously a railroad would have far-reaching consequences and incite a boom in this isolated, resource-rich place. Therefore everyone was talking about the railroad. How soon would they be linked to California and the Willamette Valley? What influence would the railroad have on the future of the region? In small towns, people lived partly in hope, partly in fear: in hope that the railroad would bring undreamed-of prosperity; in fear that the railroad would create competition in the form of new towns. Grass would grow in the streets of old ones, pessimists predicted, or immigrants would pour in and grab all business for themselves. An unbroken, 57-mile drive featured many charming landscapes. Noon found us at the little town of Oakland. Tucked away among mountains, it seemed to me unhappily located. Heavy rains made its streets anything but inviting. I was glad when the stage climbed the hill to the hotel. From the skewed veranda, as if from an aerie, as calm and complacent as could be, I looked down on greasy Oakland, flooded with rain. "Greasy" is the right word for the Umpqua Valley in the rain. Every Oregon traveler suffers nightmares of Umpqua mud. We ate our meal, which was far from sybaritic; left Oakland for Roseburg, and I got my bad memories of Umpqua mud. The black soil was so gooey from the last rain that it packed itself into the spaces between the spokes of the wheels, filled them, and clung there. Every few hundred paces we had to pause; the six-horse team could drag the mud-bogged stage no farther until we cleaned out the wheels with fence rails. Very tiresome work, from which the driver excused only the blind music teacher. Surroundings remained charming and would have been a scenic joy but for Umpqua mud. Low, forested hills, and larger heights, enclose many green valleys, each usually home to only one farm family: rare is the valley with two or more houses. Farmers here typically buy land in the basins and exploit the contiguous forested hills as excellent pasture, free, because nobody buys them. The farmer who can call this little paradise home, after the railroad arrives, will be among the most fortunate farmers in America. After we crossed the North Umpqua by ferry and distanced the few houses of Winchester, we came to Roseburg. I spent the next day there. I liked that friendly town of 500 on the South Umpqua. If the unpaved streets suffered from the latest rains, the environs--green fields, softly undulating hills and groves of myrtle, oak and acacia--were splendid. Except Jewish businessmen and brewers, there are few Germans in the Umpqua region, and they are sadly Americanized. In Roseburg, in the presence of Americans, I spoke German to a German innkeeper. He flushed in shame because I callously exposed him as a Dutchman to them. He answered in English that he forgot his German long ago. Roseburg is one of the world's healthiest places. The physician who thought he could live on his fees would starve. Nobody is ever ill. Everybody looks fit to live to 100. The mortality rate is 1:500. The last death occurred in the spring of 1870, or so I was told. Indeed, all Oregon is healthy: the 1870 census establishes it as the healthiest of the Union's states and territories, except Idaho. Roseburg has a newspaper, but intellectual fare seems not to the taste of the vibrantly healthy people. The weekly Plaindealer maintains a precarious existence. The publisher of a second, The Ensign, almost starved a year and a half before I was there, because Roseburgers did not subscribe. Sensibly he decided to raise sheep and now wields wool clippers rather than a paper cutter. I found that secluded community agog (as would be expected) over the coming of the railroad. As in all the Umpqua, it was every day's chief topic. Outrage flamed at Mr. Holladay's arrogance. He wanted, as a gift, sixty valuable acres on which to build a station. The railroad must come to Roseburg, people retorted, and they were not going to be perturbed by some millionaire! No, they were not, God forbid! But they will reconsider; good sense tells them, as it has told all small Oregon towns, to be happy to have Mr. Holladay take their gift rather than build a station miles away and create a new and competitive town. (Roseburg, I understand, has since become the Oregon & California's southern railhead--of no little significance to a small, inland town. Transshipment creates much business. The people of Roseburg are probably the only ones in Oregon happy with the railroad's financial troubles.) [Construction of the railroad southward didn't resume until 1883.] I left Roseburg at 10:30 p.m. on September 28, six hours late because the rain delayed the stage: it had to flounder through the Umpqua mud. The canyon pass of Umpqua is the only link between the Umpqua and Rogue River valleys. Some twenty years ago, before this road was built, travel via the pass was the terror of emigrants headed from California to the Willamette. They often needed five or six weeks to struggle through the thick forests. [After the route's first year, 1846, the Umpqua Canyon was typically traversed in one day.] Traces of the old trail were visible yet: I noticed several jumbled heaps of logs where emigrants had cut their way in virgin timber. Dark forests still blanketed the slopes on both sides of the narrow pass. Several times near us a prowling panther screamed its characteristic scream, like that of a child. The horses, scenting the panther, were scarcely to be restrained. The stage jolted along as if about to break to bits. One bright day, seven riders entered this pass--to a most interesting encounter with a panther. They rode at ease, smoking pipes, guns on their shoulders, talking eagerly, suspecting nothing amiss. A huge panther sprang out of a tree and onto the rump of a mule on which a rider was sitting comfortably. The situation suddenly changed, as you can imagine. Nobody thought of shooting; they clubbed at the beast with their guns, shrieking, while the mounts pranced and reared, kicked in all directions, snorted, and tried to bolt. The clubbing drove off the panther. In a leap it disappeared into a thicket. Now the riders remembered their guns as guns and fired a volley into the thicket. The volley obviously never touched the panther; it was seen moments later on the mountainside, bounding across a clearing and making good its escape. It must have been starved to have launched that attack, the like of which has never occurred hereabouts. While the civil engineer was telling that story, we emerged from the shadowy pass, happy to have encountered in its confines no such adventure with the panther we heard scream. We were at Canyonville. [Kirchhoff is mistaken--Canyonville is at the north end of the Umpqua Canyon.] At daybreak was pulled into the stage station called Levens, forty miles from Roseburg, amid the headwaters of the Rogue River [the headwaters are actually on the slopes of Mount Mazama] and a complete change in landscape: more forests than in the Umpqua Valley, a reddish-loam soil that seemed cold and unreceptive to agriculture, and a few neglected farms. Fences in bad repair, and fields idle for years, testified that the farmers thought improvement a waste of time and effort. Fruit, prodigally abundant in northern Oregon and to be bought for almost nothing there, was rare here. We looked for fruit trees around scattered houses along the road but saw very few. The stage hastened downhill at a trot on the worst of corduroy [road] and over rough terrain. We passengers, bouncing like dice, implored the driver to slow down. He laughed and whipped up the horses, saying he would regain time lost in Umpqua mud. Cow Creek gushed beside us through the forest--as if, with its loud rush, it wanted to make fun of our troubles. It twisted and turned, and we crossed it several times on the most hellishly inadequate bridges under the sun. Their surfaces were of poles laid side by side across round stringers. The poles, being loose, sprang high with a clatter, as if leaping for joy, when a vehicle passed rapidly over them. Meanwhile, now and then old gnarled oaks poked a limb and its tresses of moss into our windows archly; or scraped branches with a rattle across the roof, as if to delight in our grand passage. We breathed easier when those pole contraptions lay behind us and we reached a smooth road in open countryside. At the next stop I took a seat on the box, better to see the sights. The weather became superb as the sun climbed higher. A clear, deep-blue sky arched over a ruggedly romantic landscape. Atop a stony ridge the driver pointed out to me a solitary round boulder on the left near the road. The Umpqua Indians used to make pilgrimages to it, to worship it, he told me. "Stop," I said. I dismounted for a closer look but saw neither marks on it nor anything unusual about it. Did the Indians respect it as a god? What was their relationship to it? I could not answer. The road went next through big timber. In it a confusion of half-burned tree trunks remained of a forest fire. The hillsides abounded in the reddish-brown manzanita shrub. We met a wagon heavily loaded with its wood, an article of export. Grants Pass, sixty-five miles from Roseburg, surprised us with a splendid long-range view into the Rogue River Valley. Here and there we passed abandoned placer mines. Later, however, miners were busy when we reached the foaming Rogue. A half-dozen large and small water wheels dipped broad scoops into racing currents and sent water to where miners (Chinese) rolled up the gold-bearing earth [in carts or wheelbarrows] and shoveled it into sluices. A lively and colorful picture! We left the Rogue for a while and crossed a tributary, Evans Creek, broad and shallow. The panorama of forest and mountains was sublime, reminiscent of the world-famous scenery of the Sierra Nevada. Rays of the setting sun illuminated the mountains so as to define vividly the tall spruces on green slopes. Indeed, the sun worked wonders to set before the eyes a landscape of captivating charm. Only the frequent remains of abandoned mining camps sullied spectacular nature with monuments to vulgar civilization. An old stockade [likely Fort Birdseye] near the road recalled bloody wars with Indians that raged in southern Oregon as late as the 1850s. Once the Indians realized the hopelessness of further resisting thousands of gold-feverish whites pouring into the area, they buried the hatchet and became the most peaceable creatures on God's earth. Gone is their old, heroic pride. Meet a group now, in their beggars' rags, and be at a loss to imagine them the offspring of martial Umpqua and Pit River tribes who for many long years contested with desperate bravery every foot of land gained by whites. We returned to the Rogue. Clear currents swept toward us between rocky banks that varied from 50 to 200 feet apart. I saw several large wheels turning slowly in fast water: placer mines in operation. Pretty houses and well-situated farms graced both banks. Thick in the fields stood corn heavy with golden-yellow ears--proof we were rapidly nearing an area of considerable settlement. At the friendly hamlet of Rocky Point, thirteen miles from Jacksonville, we crossed the Rogue on a long, high, wooden bridge. Rocky Point's name tells the story: the riverbed is full of black rocks, and in one place they form a mound on the bank. The bridge was anything but a model of perfection. A German teamster would have thought twice before entrusting himself, his vehicle and his animals to that rickety affair over that rambunctious river with those rocks bristling below. But safety is not so great a concern to Oregonians. Our driver proceeded slowly with the four horses and the heavy stage while the bridge groaned at every inch and creaked in each joint--enough to give a cautious person pause. On the railing a patent medicine ad in big, white letters announced "Unk Weed Remedy" for fever. This may have been the thousandth time I read one of those ads. "The thousandth" because the ads seemed to have dogged me from Portland. On every fence, every large tree, every prominent boulder, on pigstys, on houses, and on and on were painted the same words to catch the traveler's attention: "Buy it! Buy it! Unk Weed Remedy! Oregon Rheumatic Cure!" These ads, said to occur as far away as San Diego, must have cost the medicine's manufacturer a pretty penny. But, in America, humbug earns the fattest profits. A few miles more and we left the Rogue's canyons for fertile, level valleys and the fields, forests and farms around Jacksonville, most important city in southern Oregon. At 5:00 p.m. we rattled through its streets. We had covered ninety-five uninterrupted miles since we left Roseburg the night before. Jacksonville's population, about 1,500, is heterogeneous: Chinese well represented; Germans around one-third of the total. Irish, Portuguese and Kanakas also numerous. Kanakas win esteem as energetic workers in the gold mines. Jacksonville owes its existence to the discovery of gold in southern Oregon in 1850. In its heyday, Jacksonville rivaled Yreka, California, and the output of its placers remains significant. Jacksonville is nothing like a mining town, where the people rush around in a feverish passion. Jacksonville suggests an ordinary, quiet American country town. Complaints mushroom about the recent years' drought. Though the placers are still rich, output has dropped from $300,000 to $35,000 a year, due to lack of water. In the evening the town turned out to hear the lightning calculator address "the intelligent people of Jacksonville" by torchlight. He lectured on arithmetic and expounded a simplified method of reckoning. Using blackboard and chalk, solving the most complicated problems with amazing swiftness, he totted up a yard-long column of large numbers in a flash and multiplied billions and quadrillions like a master magician at a simple trick. Abandoning the blackboard for his head, he answered questions from the audience rapid-fire and figured interest at a speed the likes of which I never saw. He talked big with incredible grace the whole time and told anecdotes until "the intelligent people of Jacksonville" stared open-mouthed and cheered with rapture his every witticism. At the end he offered his book ($3.00 a copy, soft cover), saying it revealed all his numerical wizardry in 144 pages. It sold like hotcakes. I had watched the delightful performance in several towns each evening for a week; here in Jacksonville the lightning calculator outdid himself. During my final journey from Oregon to California, in October and November of 1875, I was in Jacksonville again. The roads were dreadful; a rain worthy of the Flood imprisoned me for two days. The hotel had burned down, so I lodged with a French woman [Madame Jeanne DeRoboam Holt] who spoke broken English and looked more like an Irish washerwoman than a midwife [sic]. To stimulate appetites, her dainty little daughter played heart-rending fantasies on an out-of-tune piano while almost unpalatable meals were served. Unique music for the table, it always had an admiring audience. My stage was stuck in a swamp near Cow Creek. At midnight, tossing and turning on a hard bed, trying to find a spot softer than a broken spring, I heard suddenly, above the storm and rain that raged around the house, a clatter I took to be the stage from Cow Creek. My traveling companion thought likewise. Not to miss it, we dressed hastily and rushed into the hall. The stout French woman, in the most alluring of negligees, met us and shouted: "Only di dog, schentlemen! Only di dog!" Nero had broken loose and was dragging his heavy chain about the house. We mistook that dragging for the rumble of a stagecoach's wheels. The scene, so comical we forgot our troubles for a while, still competes with the lightning calculator's lecture during my earlier visit for my most prized remembrance of Jacksonville. I continued my journey in the morning, October 1. In splendid weather we went merrily along a good road through a well-cultivated region and past fields picturesquely dotted with broad-branched oaks. Ahead: the Siskiyou Mountains. Siskiyou, an Indian word, means "bobtailed horse." According to the lively Indian imagination, the mountains are supposed to look like such a horse. I could not puzzle out the faintest resemblance to a horse, bobtailed or any other shape. [The reference is to a favorite saddle horse that died in 1829 on one of Alexander McLeod's trapping expeditions, not to the appearance of the mountains.] Fifteen miles beyond Jacksonville we passed to our right a hot sulfur spring and its bath house. Soon we were in Ashland, an attractive place, the southernmost town in Oregon. Here the Siskiyous begin. I observed the sizable buildings of a woolen mill and a stonecutting works. Here to my joy, the blind and contentious music teacher left us. A member of the Oregon legislature replaced him and stayed until Yreka. Unfortunately the exchange was less happy than I expected. The statesman's crudeness quickly made him insufferable. He asserted the quaint notion that children should not be in school before age eleven. Let them run free until then and develop their bodies, he said. Far better than languishing in school, where, as everyone knows, they learn nothing but inadvertence and foolishness! Most of his colleagues in Salem felt the same way, he continued. He hoped the state would quickly translate this salutary principle into law. Indeed, he boasted, he didn't start school until he was fifteen, yet he learned enough to sit in the assembly of his enlightened state. Of course the rest of us held our tongues and hung our heads before this Solon of Oregon. How could we argue against proofs like this? We had the noon meal at Mountain View Station [most likely the Mountain House]. In front of the inn a large sign stretched across the way. "Tole road," a misspelling of "toll road," glared at me and evoked unkind thoughts about the enlightened state of Oregon. Then we headed into the mountains behind a team of six horses. The well-built road wound gradually up slopes and among handsome stands of evergreens. At the top we enjoyed a magnificent, long-distance view of blue, thickly forested chains of mountains. Above all, to our left, towered 14,440-foot Mount Shasta, also called Shasta Butte. What a grand panorama! The road twisted rapidly downward. On the left rose an isolated, conical rock formation, Pilot Rock. Frémont used it when surveying as a landmark. New prospects of mountains, each more beautiful than the last, delighted the eye. Now an idyllic meadow nestled bright green among the dark firs; now a brook rushed foaming down the mountainside, its banks charmingly lined with maple, cottonwood, white-trunked birch, and golden-yellow-leaved swamp ash; and always the dark-violet mountain ranges swept graphically to the horizon, while old Shasta's silver dome reached into the ether. At Cole's Station, thirty-five miles beyond Jacksonville, the principal chain of the Siskiyous lay behind us. The friendly building with the long, white picket fence looked very summery; the air had a southerly warmth; and the landscape of brown hills began to appear truly Californian. Our way intersected Oregon's southern border 400 yards beyond Cole's Station, at 42° north latitude. Dusty roads beside abandoned placers led to the California mining town of Yreka, not far off. My journey across Oregon was over. Frederic Trautmann, translator, Oregon East, Oregon West: Travels and Memoirs of Theodor Kirchhoff 1863-1872, pages 137-149 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Senator H. W. Corbett was in town during Sunday last [October 1]. He informs us that he will use every effort to enable us to obtain proper mail facilities during the next Congress. "Mails," Democratic Times, Jacksonville, October 7, 1871, page 4 LIGHTNING CALCULATOR.--Saturday night a Mr. Cromer assembled the citizens by torchlight on the corner of California and Third streets, and proceeded to address them on his new system of notation. He made a very interesting address, illustrated by numerous practical examples. Democratic Times, Jacksonville, October 7, 1871, page 3 Senator Corbett gave us a call as he passed through en route for Washington. "Personal," Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, October 7, 1871, page 3 THE LIGHTNING CALCULATOR.--We were edified as well as happily amused on last Saturday evening by Mr. Cromer, one of the authors of Haworth & Cromer's Lightning Calculator, who stopped overnight at this place and delivered a short but novel and interesting little speech. His apparent object is to introduce a better and more rapid system of mathematics, or a faster way of calculating numbers than we have ever been taught heretofore. We think the system that he is trying to inaugurate, a good one, or perhaps had better say, we are so impressed, for really he went through the examples that were given him with such swiftness that our thinking propensities were lost in utter amazement. For us to retain enough of what he said, to think about it is about like taking the accurate length of a flash of lightning. We hope, however, that our thoughts on the question will come to us after [a] while, and when they do, we will try and investigate the matter. He has our best wishes, and we hope that he may give us another call--another shock of his lightning may electricity us [sic] so that we can have clearer ideas of what he is trying to teach. But we must confess that our brains are somewhat addled on the subject at present. Oregon Sentinel, Jacksonville, October 7, 1871, page 3 Last revised December 31, 2013 |

|