|

|

A Night in Chinatown

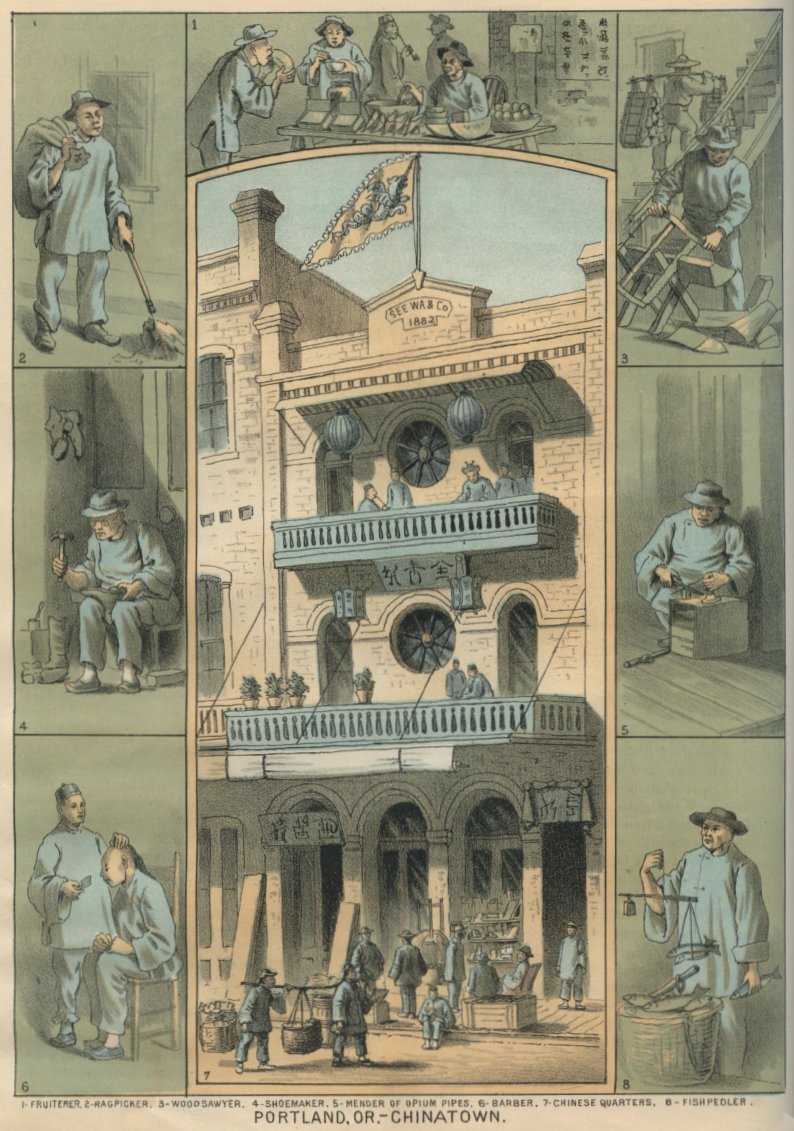

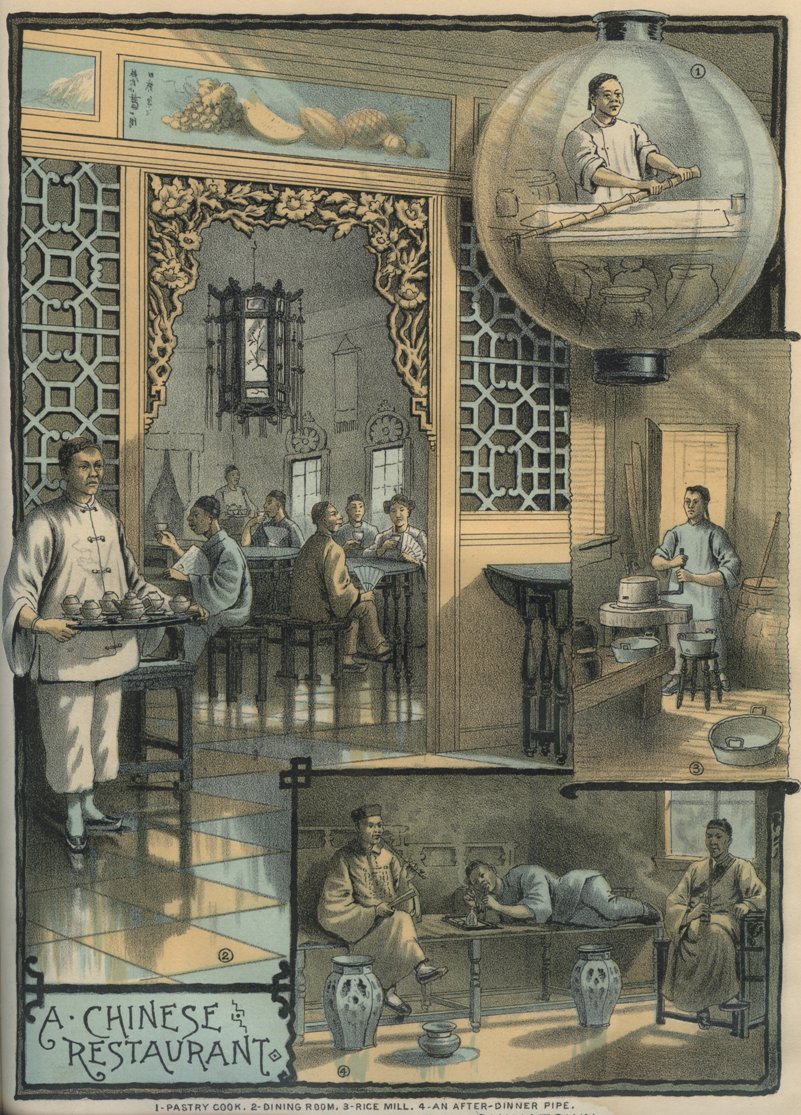

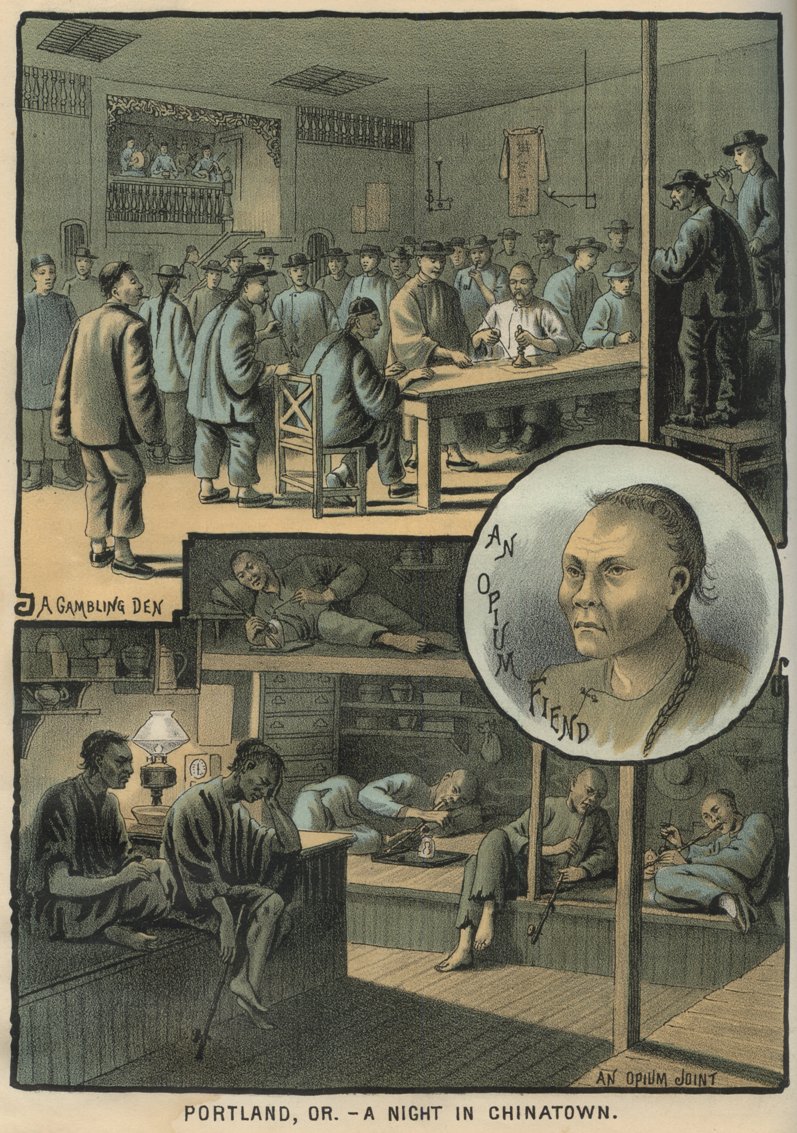

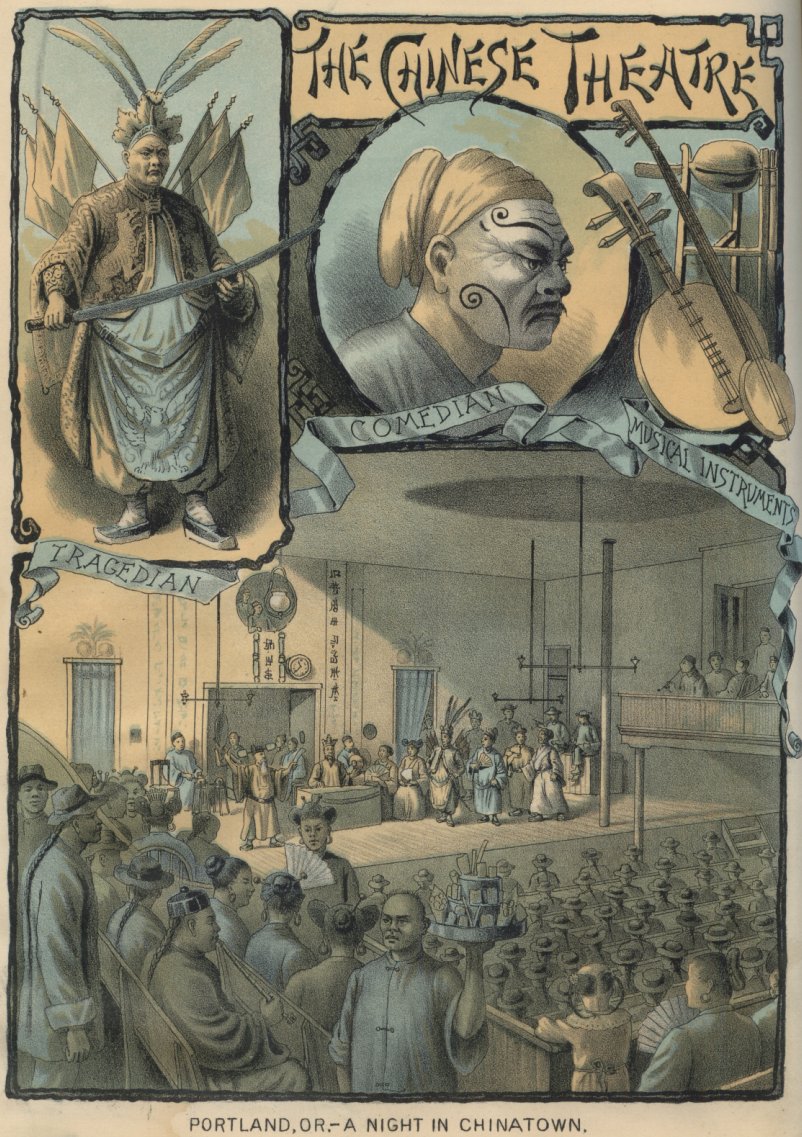

In 1886, the Oregon magazine The West Shore mounted an expedition into Portland's Chinatown and published the article below, a rare in-depth report of 19th-century urban Chinese life in the Pacific Northwest. Click on the pictures for a larger view.  A NIGHT IN CHINATOWN. The great mass of Chinese in America are of the laboring class, unmarried and irresponsible. Bound to no locality by family or property ties, they go from place to place wherever employment can be secured. They huddle together in the "Chinatown" of our various cities, from which they go out singly in search of work, or are sent out in gangs to fill contracts for labor taken by some "boss Chinaman," returning promptly to the city rendezvous whenever out of work. Only those of the better class, the merchants, bosses, etc., can afford the luxury of a wife and family. A wife represents an investment of from one hundred to five hundred dollars purchase money, and a steady outlay for current expenses. Consequently they are above the means of the ordinary coolie, and are a scarce article in America. The great majority of Chinese women brought to this country are of the disreputable class. They are not very numerous in comparison with the men, yet they amount to several thousands in the aggregate; and since they remain in the cities and are there seen in great numbers, they give the impression of being in greater force to the men than is actually the case. Every effort is made by our customs officials to exclude them under the terms of the restriction act, and of late years their numbers have not increased as rapidly as formerly. There is one class of Chinese who acquire and maintain property interests here--the merchants. They are of a higher order than the mass of their countrymen who reach our shores, and the two are as distinct socially as the same classes are among our own people. Their property consists chiefly of merchandise, and it is seldom they acquire real estate. Some of them, however, have erected buildings upon land held under a lease, while a few have even gone to the extent of purchasing the land itself. Some of these are rich, even in the American acceptation of that word, while all of them are well-to-do according to the Chinese standard. They are shrewd business men, and possess as fine a sense of commercial honor as do the white merchants occupying more imposing quarters on the adjoining street. Their dealings are principally with their own countrymen, though our wholesale and commission merchants have quite extensive transactions with them, and find them desirable customers. They have a commercial system of their own, and it is seldom our courts are troubled with their business affairs. The majority of respectable women are wives of these merchants, and generally live in apartments in the rear of, or above, their husbands' stores. They are seen but little on the street, are modest and retiring in their demeanor, and are usually dressed in the most expensive silk and velvet. They toil no more than the lilies that put the glory of Solomon to shame, but are considered by their husbands more as toys and ornaments than as companions and helpmeets. Their domestic duties are practically nothing, since all cooking is done by men, and they have but the care of their children to occupy their time, when, indeed, these little almond-eyed olive branches begin to spring up around them. In every city of any size on the Pacific coast there exists a miniature China, with the exception only of the pagodas and other forms of native architecture. The quarters they occupy are generally in the heart of the city, comprising brick structures formerly used by our own merchants, or others which have since been erected by themselves, of the severest plainness in their exteriors. With this exception there is little in the appearance of Chinatown to convince the stranger that he is not actually traversing the streets of Hong Kong or Peking. The interiors of the old buildings have been remodeled to meet the Chinese idea of utility. Half stories have been put in, and the whole cut up into innumerable small apartments and passageways. Everywhere there is the utmost economy of space and prodigality of smell. In their new buildings little windows reach these half stories and let in the faint rays of light and the small breath of fresh air which seems to be all that Mongolian lungs require. Half a dozen of them will remain for hours in an inside apartment so contracted that they can hardly move about, with no ventilation save what creeps in through a small door from a dark and narrow passageway, and where the atmosphere is so foul and the conglomerated odors so rank that a white man finds it unendurable. The ordinary observer beholds Chinatown only in its exterior aspects. He sees the walls plastered with red paper covered with the complicated marks which convey intelligence to the Mongolian, interspersed with the gaudy bills of some circus or dramatic troupe; he sees the stores, with their English and Chinese signs staring at each other with the appearance of hopeless estrangement; the roast pig, hanging tail upwards; the butcher clumsily cutting up pork, which seems to form almost their entire meat diet; the barber shaving the heads and braiding the queues of his customers, his paraphernalia consisting of a common chair, a bowl, a towel and a razor; the cobbler and tinker at work on the sidewalk for the purpose of saving rent; the vendors of vegetables, confections, cigars, etc., at their little stands on either side of the walk; the fish dealer, with his basket and scales, at the curbstone; the rag picker, with his gunny sack and stick, and scores shambling along at a dogtrot under the weight of loaded baskets suspended from the ends of bamboo poles. He may even enter the store and see their varied stocks of Oriental goods, where he may find in progress a game of dominoes or see a party sipping tea and cramming their mouths full of rice with chopsticks; may visit the joss house, restaurant and theater--but without a qualified guide he will fail utterly to become acquainted with the interior and less known features of Chinese America.   Our next visit was to a lodging house, which was simply a brick building cut up into innumerable small rooms, making a perfect labyrinth of passages, doors, apartments and stairways. Bunks of wood are arranged in tiers against the walls and partitions like the berths on a steamer, and upon these the lodgers stow themselves away for the night, a dozen of them occupying a room so small, so foul of atmosphere and so permeated with vile odors, that a white man would deem it an unendurable prison. When they can find such lodgings as these for ten cents a night, and can supply themselves with food during the day for ten cents more, it is no wonder they can save money on seventy-five cents a day. We saw one street merchant whose sole stock in trade consisted of a little table with folding legs, a small butcher knife and a watermelon. The latter cost him twenty cents, and was cut into ten slices and retailed at five cents a slice. If he sold it all he cleared thirty cents by the operation, giving him enough for his board and lodging, and ten cents surplus, which he could save or gamble away as he saw fit. If business was good enough to call for two melons during the day his profits were proportionately larger. While we were watching him, two young Chinamen came up, and one of them, fishing a nickel out from the depths of his raiment, purchased a slice of melon and divided it with his companion. It was evidently his treat, and showed that the reckless liberality of the American displayed in the social custom of treating has its imitators among our heathen visitors. It is by Chinamen who saw wood, pick up rags, do odd jobs of work, keep these little tinkering corners and stands, and the gangs from the country, that the lodging houses are patronized. If one has been sufficiently provident to save up ten dollars, he can subsist at least two months without employment. This question of board and lodging is one the Chinese have reduced to its finest limit, but Caucasian civilization will never be satisfied to adopt their solution of the problem. From the lodging house we were conducted to a gambling den. It was necessary first for our guides to send word to the proprietor that visitors were coming. Had the policeman undertaken to enter without giving warning that their visit was a friendly one, they would have found it a work of at least two hours to break in with sledges and axes. Opening directly from the street, and running back to the interior of a brick building, was a narrow passage, through which we went in single file. At the street entrance stood two sentinels, or lookouts. A few feet inside was another whose duty it was to adjust a set of upright bars upon receiving a signal of danger from without. Beyond these were three thick, wooden doors, each guarded by a lusty Chinaman who was alert to close it and secure it with a heavy crossbar when an alarm was given. In making a raid the police would have to batter down all these obstructions, only to find, upon gaining the interior, that no gambling was in progress, but that a lot of Chinamen had assembled to engage in social conversation and to enjoy the dissonant music of a native orchestra perched upon a diminutive gallery at one end of the room. Upon such circumstances it is impossible to make a successful raid, and none is attempted. The police are permitted to enter at any time when assurance is given that their visit is of a friendly nature, and this promise is never violated. This freedom of access to gambling dens, opium joints and lodging houses is of great assistance to the officers when searching for criminals, and this mutual understanding between them and the proprietors saves the officers infinite trouble and annoyance and the proprietors the expense of replacing battered doors and fastenings. Once inside, we were met by one of the managers, who courteously explained the mystery of the only game in progress. We found a long table surrounded by players and spectators, while others occupied a little gallery just above and dictated their play to friends below. Near either end of the table was marked a black square about ten inches on each side, while at one end sat the dealer. The latter took a handful of small pieces of metal and threw them into a heap in front of him, covering them with a bowl. The result of the game depended upon the number left in the pile after the others had been taken away in sets of four. The players made their bets by laying their money or checks at the corners of the squares, one corner representing one, the next two, the next three, and the last four. When all bets had been made the dealer lifted the bowl and began drawing the counters away from the pile in sets of four, using a stick and not touching them with his hand. His motions were keenly watched by the players, and as the pile diminished in size they set up a chattering like a cage of monkeys. By the time the heap was reduced to fifteen or twenty they could all tell just what the result would be. If the pile divided into even fours, those who bet on the fourth corner won and the others lost; if there was a remainder of three the third corner won; if two, the second, and if there was but one left, the first corner was the lucky one. There were complications of the game by which a bet could be divided or doubled, but in his efforts to explain these the proprietor got hopelessly astray in his English, and finally wound up by saying "you no sabbe." After watching the game for a few minutes, inspecting the barred cage in which the cashier enshrined himself before a huge iron safe, and taking up a collection to hire the orchestra to stop playing, we said good night and passed through the many guarded portals into the street. We were much interested in a pawn shop, and stopped to observe the Chinese method of "smoking" valuables. Within a wooden stall, accessibly only by a stairway in the rear, reached through a securely bolted door, stood the pawnbroker. The stall was so high that he could not see over it, and was surmounted by an iron railing extending to the roof, but pierced in the center by an aperture about two feet square. The needy Mongolian advanced with a pipe and holding it up, thrust it through the hole above his head, the broker taking it from his hand. In a minute a slip of paper was passed back on which was written the amount the broker would advance on the pipe. This was apparently not sufficient, for the paper was returned and the pipe handed back to the customer, who took his departure. Neither party to this transaction saw the other. By pursuing this course the broker never knows who are the owners of the articles in his possession. Across the hall from the pawnbroker's stand was a counter where lottery tickets were being sold. Chinese lottery is indulged in extensively, not only by the Mongols, but by many whites, some of the latter developing into regular "lottery fiends." For twenty-five cents one can purchase a ticket upon which are printed about forty characters. He marks a certain number of these with ink, taking one ticket himself and leaving a duplicate with the seller. Every night there is a drawing,and if he has marked a sufficient number of the winning characters he is paid a sum of money in proportion to his success in guessing. For a larger sum he can mark a greater number of characters with the possibility of his winnings being proportionately increased. It sometimes happens that a small investment brings large returns; but like every other lottery game, where one wins a multitude lose, and the persistent player is certain to drop a great many quarters into the money box. In the basement below a popular beer hall we found a saloon devoted exclusively to the Chinese. It contained a bar, seats, and an old pool table, and it was comical to see the awkward handling of the cues by these imitators of the gilded youth of America. In their potations they by no means confined themselves to beer, but indulged in mixed drinks as well. The favorite seemed to be a cocktail, which the bibulous Chinaman considers the very acme of liquids. They rested their elbows against the bar, spat upon the floor, tilted their hats upon the backs of their heads, and in other ways conducted themselves in the most regulation style. In this particular, at least, they are becoming Americanized, but the direction their education has taken is not encouraging.  At the head of the stairs we observed two door keepers, a white man and a Chinaman, a peculiarity our escort endeavored to explain by saying, "One man come, Chinaman sabbe; nodder man come, Chinaman no sabbe, Melican man heap sabbe. You sabbe me?" He was assured that his explanation was remarkably lucid and conveyed in the choicest English, whereat he smiled with pleasure. We found the interior to be somewhat similar to that of the ordinary small American theater, consisting of an auditorium surrounded by a gallery, the sides of which were divided into apartments open to the front and partially to the side, the seats being innocent of any upholstering whatever. We mounted to the gallery to obtain a better view, and gazed down upon the audience. They were packed in rows upon long wooden benches, each with his soft black hat resting squarely upon his head and his pigtail hanging straight down the middle of his back, the whole presenting the lifeless uniformity of a group of tin soldiers in a Christmas box. In several of the gallery stalls were seated a number of gaily dressed and gaudily painted ladies, evidently of the better class, dividing their attention between the performance and a package of confections. The stage consisted of a raised platform at one end of the room, devoid of curtain, flies, scenery or stage settings of any kind, even being used for seats by a portion of the audience. At the rear were two doors, the one used for an entrance and the other for an exit. Between these was stationed the orchestra, whose perpetual muscularity found vent in agonizing solos, discordant duets and the deafening din of a general engagement. The stage properties used were few and simple and were brought on and handed to the actors in full view of the audience. In the paucity of accessories, the actors resorted to pantomime to supply the deficiency, and a lively imagination only enabled us to understand whether an actor working his arms vigorously was rowing a boat or putting out a week's washing. The costumes of some of them were of the finest silk, velvet and broadcloth, but the colors were wonderfully and fearfully mixed. As we turned our attention to the stage, it was occupied by a coy maiden who was singing or reciting in an expressionless falsetto voice something which seemed to be highly pleasing to the audience. A man with a flowing robe of blue silk flapping about his limbs, and a long beard of yellow horsehair depending from his chin, entered with a stately stride and began making love to the maiden, apparently without making a favorable impression upon her. They soon retired, and a lusty fellow with his whitened face seamed and crossed with streaks of black bounded in and pranced across the stage as though his shoes were swarming with red ants. Hew as evidently the "bad man" of the play. He disappeared, and the coy maiden again glided into view, this time accompanied by a comely youth whose amatory advances were evidently more pleasing than those of her more aged lover. Matters apparently soon came to a focus, for immediately after making their exit, they rushed upon the stage again, hotly pursued by the rejected suitor and the "bad man," the latter waving aloft a long paper sword whose flimsy blade flapped from side to side as it clove the air. Both parties disappeared and soon the fugitives made a breathless entrance at the other door, having apparently gained half a mile in the twenty seconds of their absence. In the center of the stage they stopped suddenly and started back with horror, having evidently almost fallen over the brink of a chasm which was visible only to the eye of the imagination. They began to construct a bridge, and with the aid of some assistants, two tables were placed about four feet apart, cross which a plank was laid, and a chair set at either end for steps. While the bridge was being constructed the chasm obligingly disappeared so they could cross back and forth freely; but when all was ready the chasm was again in full force and effect. The fugitives then crept cautiously across the impromptu bridge and ran joyfully away. Then appeared in hot haste the "long beard" and "bad man," who also "viewed with alarm" the imaginary chasm and seemed greatly perplexed by the situation until they espied the bridge, against which they had been leaning while discussing the problem. They also crossed timorously and rushed away. As the plot thickened and the face of the moon was more and more tinged with gore, the writer became deeply interested. He suggested the propriety of remaining to see the end, and was plunged into confusion by the scornful laugh which broke from the lips of the entire party. The manager then explained that a Chinese play is built on the broad-gauge plan, like a continued story, running day and night for many days, and that the one we were now looking at began the week before and might possibly be concluded in another fortnight. The obliging manager then conducted us through the audience and across the stage to the room in the rear, passing unscathed through a bloodless conflict between a parcel of gorgeously appareled gods and a batch of hideously painted devils, who were hacking each other with paper swords to the merciless clash of the orchestra. The one long room at the rear of the stage served for dressing, property and waiting room, and was crowded with actors and assistants. The first thing we noticed was that the coy maiden was no coy maiden at all, but only a horrid man, as were several other supposititious [sic] females, and we were informed that there are no women actors among the Chinese, all female characters being taken by men, who are considered the leaders of the "profesh." We found the actors to be socially inclined, especially the "bad man," who shook hands all round, and smiled as benignly as his black streaks would permit. After watching for a time their entrances and exits, and after examining and duly admiring their multitude of costumes and trappings, we descended a ladder into the dark space beneath the stage, which is not devoted to the purposes of the play, as in other theaters, but is cut up into numerous small apartments where the actors sleep. Between the stage and the ground we found three separate floors, none with the ceilings more than seven feet high, and one of them so low that we had to stoop in going from one side to the other. We glanced at the kitchen, which was an apartment against the interior brick wall, about ten feet long and four feet wide, and filled with a smell ample for a large hotel. Declining an invitation to partake of something the exact nature of which was involved in mystery, we murmured our thanks and groped our way along a narrow passage leading to a side door, issuing out upon the street, glad to fill our lungs with the fresh night air and give our olfactories a well-earned vacation. HARRY L. WELLS

The West Shore, Portland,

Oregon, October 1886, page 295

A CHINESE FUNERAL.

As an overwhelming exhibition of grotesque ceremonies and imposing

awkwardness, the Chinese funeral stands unrivaled. However impressive

it may be upon the minds of the followers of Joss, to the unregenerate

heathen of this country the spectacle is supremely ludicrous. Neither

pen or pencil can convey to one who has never witnessed the scene an

adequate idea of the manner in which the numerous ceremonies are

performed. Neither grace nor dignity is exhibited in any portion of the

service; unless striding jerkily about in a long flapping robe of white

cotton, with the head bandaged with a piece of the same material, may

be considered dignified. Grace, there is none to be found in any mode

of Chinese locomotion; in the ordinary shamble of the lounger, the jog

trot of the coolie between his burdens, or the supposed stately stride

of the dignitary; and when all these are combined in a funeral

procession, the effect upon the Caucasian observer is far from

impressive.

The ordinary Mongolian, when he departs this life, is enclosed in a pine coffin and carried to his temporary resting place with but little ceremony. The procession generally consists of the hearse, a hack containing two or three musicians, and an express wagon bearing the blankets and other worldly effects of the deceased, and an array of roast pig, rice and other edibles in quantity and quality such as he had probably never been able to enjoy while living. It is only when a man of wealth or position dies that the genuine funeral service is performed making it an event sufficiently rare to be always novel. Not long since one of them became weary of the follies and vanities of the world, and severed the slender cord of his life with a butcher knife within the sacred precincts of the joss house. Whether the place of his death entitled him to special distinction in his funeral, or whether he had friends or relatives sufficiently wealthy to pay the expenses of such an event, cannot be stated; at any rate he was buried with much ado and ceremony. A temporary canopy and three tables were constructed in the street in front of the joss house, where the body lay in state. Upon the tables were placed a whole roast pig, bowls of rice, confections and a mass of eatables and drinkables that would have been a banquet for a score of men. Burning punk, paper prayers, fluttering banners and numerous odd and fantastically colored devices completed the scene. About these was gathered a motley crowd of spectators of both races, within whose enclosing circle white-robed priests performed the various ceremonies of the occasion. They bowed themselves successively upon mats, sometimes singly, sometimes in pairs and at times three together, repeating the performance at both sides of each table, reciting some form of supplication as they touched their foreheads to the ground. For nearly an hour this performance was carried on, a constant clatter being maintained by two Chinese bands occupying hacks stationed near the tables. The spectacle culminated in a procession, which was intended to be imposing but was simply ludicrous. After much running backward and forward, wrangling and chattering, the different elements of the pageant were properly placed and the line of march was taken up. The most difficulty was had in placing two white-robed musicians, who were evidently an important factor in the display. Each bore across his left shoulder a long pole, from the rear of which fluttered a banner, while a gong depended from the end held in front. Upon these gongs they beat at irregular intervals. They first took the head of the procession, then were moved to the rear, then given a place in the center, and, finally, after a start had been made came trotting to the front and stationed themselves immediately behind the hearse. At this point a Chinaman ran towards them excitedly for the fifth time and snatched form their heads the dirty black hats they had forgotten to remove, revealing two red turbans that made quite a transformation in their appearance. When fully in motion the cortege consisted of two couriers on horseback, who could neither keep abreast of each other nor in the middle of the street, a carriage with a band, the hearse, the two red-turbaned gong beaters, a standard bearer with the gorgeous three-sided ensign of China, an array of white-robed priests, an express wagon with the trunk, blankets and other personal belongings of the deceased, another discordant band, and sixteen hacks. In marching they neither kept step nor aligned themselves to the right and left or front and rear, but each man made progression as seemed to him the most convenient and, apparently, the most awkward. It was a spectacle that must be seen to be appreciated, but the artist has represented on page three hundred and six as near a representation of the scene as possible, for the benefit of those to whom a sign of the original is denied. The West Shore, Portland,

Oregon, October 1886, page 307

Last revised July 24, 2009 |

|