|

|

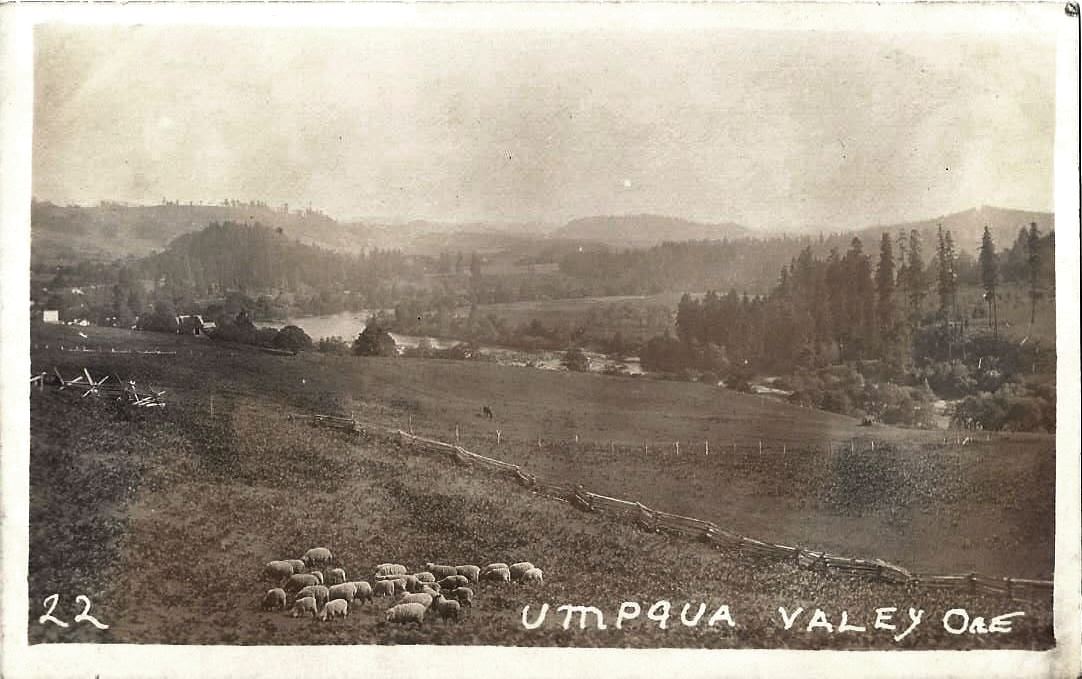

Jackson County 1874  The Umpqua Valley circa 1910. What a struggle nature keeps up to bring us to the needed rest of sleep, and how successfully the stagecoach combats and battles all such efforts. Just as this strife is rendering us quite desperate there is a rattle of wheels between buildings, the road for one instant seems smoother, and the coach strikes a livelier pace as it rounds to at the low porch of a wayside country tavern. And here, it seems, we are to breakfast. Breakfast in the darkness of night, and before we have enjoyed the first sweet nap, is mere irony and bitter mockery. The meal that is set before us too would be but mockery under the brightest of circumstances. Soggy are the biscuits; muddy is the coffee; most forbidding the pork swimming before us in a lake of its own fat; our breakfast room was but a few minutes before a bedroom, and the change is too recent to admit of any attempts at concealment or evasion of this unpleasant fact; the one lamp sputters odorously and sheds a dubious glow on the inexcusable foulness of the tablecloth; bah! let us out! Oh, incense-breathing morn, what a profanation of thy cheery meal is this! and why are we made to stand and deliver "six bits" in good solid coin for merely snuffing the combined odors of that banqueting hall? The stage is at the door with fresh horses and a fresh driver. We embark once more, now thoroughly awakened and indeed refreshed by the half hour's stretch of legs, if not by the breakfast. It is still black night, but we light cigars confidently and feel that we have begun a new day. The day is not long in reddening the eastern sky, and we watch joyfully the sunrise, from its first flush to full effulgence. And when by and by the warm glow cheers us into an appreciative sense of our surroundings, we find ourselves in a wild mountain region. Rugged and grand, fir-clad and rocky, they tower about us with no longer any semblance of sequence or continuous range. There are here and there farms and settlements along watercourses and in the small valleys--beautiful spots, too, looking rich in fruits and golden flowers. The stage road generally, however, led among the greater hills, under the lee of frowning rocks and through pine woods. It was certainly grand and beautiful, and with rather more of California than Oregon in its flora. The wayside was full of the orange-colored blossoms of the eschscholzia that so brilliantly gild all the green places of California, and the manzanita and madrona were becoming frequent. Both of these last-named are semi-tropical-looking shrubs or trees, the madrona having a bright-red trunk and limbs that contrast finely with its dark and glossy green foliage. When we next changed horses I got a chance to walk on ahead, and I could note the roadside flowers more pleasantly while resting from the weariness of sitting. And when the stage overtook me I climbed to the unoccupied seat beside the driver, and found it by far the most comfortable place on board. It was certainly exposed to the full fury of the summer sun, but then the breezes were fresher than on the inside, and the clouds of dust blew aft, or settled on the insiders; and I could see the road far ahead, and get glimpses down ravines, or of distant snow-peaks, hidden from my companions. I have heard it said that the roads on the Pacific Coast were generally good, where you might reasonably expect poor ones, and bad where they might easily be made good. This is certainly the case in the Oregon stage routes. On the plains, where nature has made things smooth, man has been neglectful, but when forced to cross mountain ranges he has done it excellently well. These roads wind from the low valley places to mountaintops, clinging to the sides of ravines, hanging over precipices, turning very short angles, but always built firmly and smoothly, and supported by log and rock walls. In some places you could almost reach from the stage to another and higher part of the same road, that it would take perhaps half an hour of travel to reach. Thus, winding and turning and climbing, looking off at the great ravines yawning below us, or up at the pines above us, or at the beautiful and sweetly odorous flowers of manzanita or azalea bushes, we climbed up to considerable heights. Then, with a loud crack of the driver's whip, we went whirling down the mountainsides at a furious rate. It seems to be customary here to drive horses at a gallop down the hills. On we go, clouds of dust rolling behind us, and the coach spinning over the smooth roadway. Where the road makes a complete double, we check speed a little at the angle and let the horses take breath, and also shout a warning to possible teams coming in the opposite direction. When we meet teams the difficulty of passing on the narrow road is considerable, though we can usually either see or hear far enough in advance to select the best ground. But the roads, good as they are, are very narrow. Now, as near noon, we find ourselves descending, I descry below us on the right a river--a river bright with foam and its crystal waters transparent and green. The driver says this is the "Rogue," so I know we have crossed the barrier and are now in the southern division of Oregon, viz, the Rogue River Valley. Pretty soon we are down on the river bank with the mountain wall crowding us close to the water. But soon the valley expands slightly, and a little town or group of houses stands at the head. Here we find a small neat tavern where we dine. There are no traces of French cookery about the dinner, but still the neatness and cleanness of the plain fare, after the breakfast failure, are very pleasant and dispose us to think well of the little village of Rocky Point. We cross the Rogue River on a bridge, and then our afternoon's drive is down the expanding and fertile valley. This Rogue Valley is narrow, but quite level and a prairie. It is but newly open to settlers, and by no means full yet, but it has been occupied long enough to manifest practically its excellence as a peach and grape district. Jacksonville, which we pass later, is a mining town, and nearby are the gravel heaps and dull yellow banks which indicate placer mining. These are generally deserted, though I saw one or two Chinamen, armed with the gold-digger's professional pan. Now Mount Pitt, magnificent and conical, its eternal snows dazzling with sunshine, looks down upon the valley, and seems hardly a dozen miles off. Yet at its feet lie Klamath Lake, and the Lava Beds of the gallant Captain Jack, eighty miles distant from Jacksonville. As the twilight approaches, we edge toward the right side of the valley, or climb the lesser foothills of the Siskiyou Mountains. A wayside supper, fresh horses, and a long, steep climb in the first darkness of the night, and we are fairly in for the night ride over the mountains. I climb to my outside perch, in spite of intense and persistent drowsiness. The great rocks and the pine trees grow spectral and dim; the creaking of the coach and the clash of waterfalls become first monotonous, then faint; the rising morn casts a ghastly light through the foliage, which flickers strangely. I fairly lose consciousness and show evident signs of lurching overboard, so that the driver stops for me to climb inside. My companions do not welcome me very hospitably, as I oblige them to take a pile of assorted boots and shoes out of my seat and to curl up into narrower quarters. But why recount the tortures of the night? Rendered desperate for want of sleep we do doze at intervals, though every such respite is followed by the loss of one's seat or a bruised and battered head in contact with strap buckles or the iron curtain button. Still the aggregate of sleep is something no doubt, and when we stop at the little town of Yreka, for for the usual change of horses at 3:30 a.m., I find a wooden office chair, in the warm and comfortable hotel office, the softest, sweetest quietest resting place imaginable. "From the Pacific Ocean," Burlington Weekly Hawk-Eye, Burlington, Iowa, February 26, 1874, page 6 The country lying between the sea coast and the Cascade Mountains, known as Western Oregon, has a coastline of 300 miles long, running north and south. It extends inland with an average width of about 150 miles to the mountains, which are lofty and rugged, and lift their many peaks into the region of perpetual snow. They form a great physical and climatic barrier, and to them Western Oregon owes its soft climate, its winter rains, forests, and verdure. From the Cascade Range also Oregon derives its supply of water, in rivers and streams which, fed from the mountain snows, are always pure, cold, and full of the finer kinds of fish. These streams afford an extensive water power, and their banks provide admirable facilities for mill sites. The face of the country is mountainous and largely covered with heavy forests. The western slopes and foothills of the Cascades extend far down towards the Willamette, where they finally disappear in the level meadows and prairie lands that border the river. The Willamette River flows due north to the Columbia, the northern boundary of Oregon. Its valley proper is from 40 to 75 miles wide and about 200 miles in length. This region is nearly all prairie, quite level, and exceedingly rich in soil. It is the principal part of Oregon, and contains four-fifths of its population, towns, and land under cultivation. Between the Willamette Valley and the ocean lies the Coast Range of mountains, which, though not half the altitude of the Cascades, is still rugged and grand, and covered with a dense forest of firs, pines, cedars, and other coniferous trees peculiar to the Coast. Below the Willamette Valley the Cascade and Coast ranges are united by a spur known as the Calapooia Mountains, which is similar in character to the Coast Range. South of this barrier lies the Umpqua River, which can scarcely be said to have a valley. It is a rapid brawling stream of bright, clear water, which forces its way through the mountain gorges and Coast Range into the sea. These hills and mountains, however, are unlike the rough and forest-clad Cascade and Coast ranges, as they are characterized by gently swelling and grassy slopes, where scattered oaks make pleasant dots of shade, and the natural pasturage is abundant. Between the hills are small valleys of great richness. Here and there the tops of the mountains run up into rocky pinnacles, which are surmounted with bunches and groves of fir and pine. South of the Umpqua again is another rough and rugged mountain range, beyond which lies the valley of the Rogue River. This stream rises near the snowy volcanic cone of Mount Pitt, and flows directly west to the ocean. East of Mount Pitt, and at its foot, lies the lake and lava country, famous as the resort of the Modocs, under the leadership of Captain Jack. The Rogue Valley is narrow, but level and meadowy, like the Willamette, with a climate more adapted for the growth of peaches, grapes, and the more southern fruits. There is here less rain than in the more northerly part of Oregon, and the climate partakes of the dry character of the California summer. Between the Rogue Valley and California lie the Siskiyou Mountains, which form the southern boundary of Oregon. An Act of Congress in 1850 granted lands to settlers in Oregon without price, or only at the cost of occupancy--640 acres to married men, and 320 acres to single men. Prior to this date there had been some desultory trading, and a few missionary settlements had been established. The Act of 1850 appears to have had a diplomatic object in view, which was to secure American ascendancy, as the old claim of the Hudson's Bay Company covered all the country to the California (once the Mexican) line. This Act, of course, stimulated immigration, and retained the former settlers, who were being strongly tempted to leave the country by the discovery of gold in California. Then came the immense demands from the diggings for farm produce, with its attendant extravagant prices. The Willamette Valley speedily filled up with rather a rude class of farmers, disappointed gold-seekers, and "Pikes" from Missouri and the further slave states. Of course, labor was scarce, and no settler could hire farm hands, while the government was giving everybody land for the tillage. Each one cultivated as much of his 640 acres as he could, and the rest of the land was left unoccupied and unused. With the fall in prices and the growth of agriculture in California, and the expiration of the Donation Act, Oregon colonization slackened and fell off materially. The "Pike" had few tastes and aspirations; the redundant soil and almost winterless climate enabled him to live with the minimum of labor, while his flocks and herds multiplied and sustained themselves without cost, as pasturage was free and perennial. This is pretty much the old story of the settlement of Oregon; the subsequent immigration has never been large, though the aggregate amount has told upon the population and productions of the state. The whole of the open lands of the Willamette Valley proper may now be said to be in the hands of private citizens and small farmers; but of the acreage so held not much more than one-tenth is cultivated. The rest is generally for sale at reasonable figures. Even "improved" lands--that is, lands fenced, broken, and cultivated, together with barns, houses, &c., may be had at $15 per acre and upwards, according to the value of the improvements. The government land comprises the small valleys, the foothills, the pine and timber lands, and the mountains. The railroad and internal improvement lands--i.e., the land granted by Acts of Congress to joint stock companies for such purposes--are precisely like the government land, and alternate with it by sections or square-mile blocks for 30 miles on either side of the line of railroad, beyond which all is government land. The government price for land varies. A citizen who occupies a tract of not over 160 acres for a continuous term of five years may receive the title to his land in fee-simple without any payment under the Homestead Act; otherwise he may buy at any time for $1.25 per acre, or if within six miles of the railroad at $2.50 per acre. The railroad and corporation land is for sale at prices but little, if any, higher than government rates, but with a long term of years granted for payment. Considering climate, fertility, and the future promise of Oregon, land is cheaper here than in any other part the United States, and it is likely to continue so until the state has a railroad connection with the outer world. What has been said of the population of the Willamette Valley is applicable to that of the Rogue River and the valleys in the neighborhood of the Umpqua, except that they are more sparsely populated. The country about the Umpqua is not so well adapted for raising grain as the others, but it is more suitable for grazing purposes. Its narrow, yet rich and sheltered valleys are admirably adapted for the production of all kinds of fruit. It is worthy of remark that freight from Portland to Liverpool is about the same as from Chicago to the same port; and, as Liverpool grain quotations govern prices to the remotest grain patch, prices in the vicinity of Portland are the same as those that rule near Chicago, except that the superior quality of Oregon grain usually gives the producer an advantage. The tourist who visits the Pacific Coast should by no means omit visiting Oregon if he wishes to gratify a taste for the sublime and beautiful. The Oregon and California Railroad runs through the whole length of the Willamette Valley then, crossing the Calapooia Mountains, penetrates well into the Umpqua Valley and terminates at Roseburg. Nearly 300 miles of road remain unfinished between this terminus and the California lines. A trip over this road takes one through wheat fields, orchards, and rich farms, through towns where there are lumber, flour and woolen mills. Shaded streets, church spires, and modern French-roofed buildings give evidence of wealth and comfort, while the snowy cones of Mount Hood, Mount Jefferson, the Three Sisters, and the wooded sides of the Cascade and Coast ranges impart an air of grandeur to the scenery. But this is far excelled by the glorious views to be obtained on the Columbia, where the scenery surpasses in magnificence anything of the kind in California or, it is said, in any part of the United States. "California," The Times, London, September 23, 1874, page 8 FROM SOUTHERN OREGON.

TO THE STATESMAN:--Talk

of webfoot mists and Willamette mud or Umpqua

"doby" as much as you like, and then come to this valley and see

heavier rains, deeper and thicker "cleman illahe" (mud) [klimmin illahie by Gibbs'

spelling--"soft earth"] than ever you saw in that

region yet. It is said, however, to be an unusual thing here

and perhaps it is; but the manner in which all classes rush out into

the falling waters and plod and drive and haul through the slush and

mud gives to the observing stranger an impression that such things are

common here, or else the inhabitants were all formerly from your valley

or that of the Umpqua, and accustomed to it.A Rogue River Rain Storm--The Miners in Glee--The Business, the Wants and the Prospects of Southern Oregon. The heart of the miner has been made glad for the last three days, as the "miner's delight" has been pouring down on the mountains and over the valleys round about here much after the style of a "States rain," but now, this morning, the "pouring act" has ceased and the clouds are breaking away here and there and the evergreen manzanitas that adorn the mountain and hillsides look only the more beautiful for the drenching storm they have withstood. Notwithstanding the cry of hard times and the great scarcity of money in this portion of the State, the sounds of industry are heard upon every hand and a number of buildings are going up here now, seven of which are brick buildings, being erected for business houses. Trade is fair, and take it all in all, the people of this county seem to be enjoying themselves well. The great want of this part of the state is railroad communication, either coastward or also to connect with the California and Oregon lines, to enable them to ship to market the product of their farms. The soil is rich and very productive, but at this time it is impossible to get the surplus crops into market. The Grangers of this valley are surveying a route for a wagon road to the coast, expecting to secure a good route thereto with a terminus not more than one hundred miles from here. When this is done, and it will be soon--perhaps times will be easier than now. I leave for Klamath on the stage this evening, going by the way of that thriving little town of Ashland, on the Bear Creek arm of the Rogue River Valley--a beautiful place, full of life and energy, and bidding fair to become a formidable rival of this place one of these days in the near future. In haste etc. W. R. DUNBAR.

Oregon

Statesman, Salem, December 5, 1874, page 1JACKSONVILLE, Nov. 25. Last revised September 22, 2024 |

|