|

|

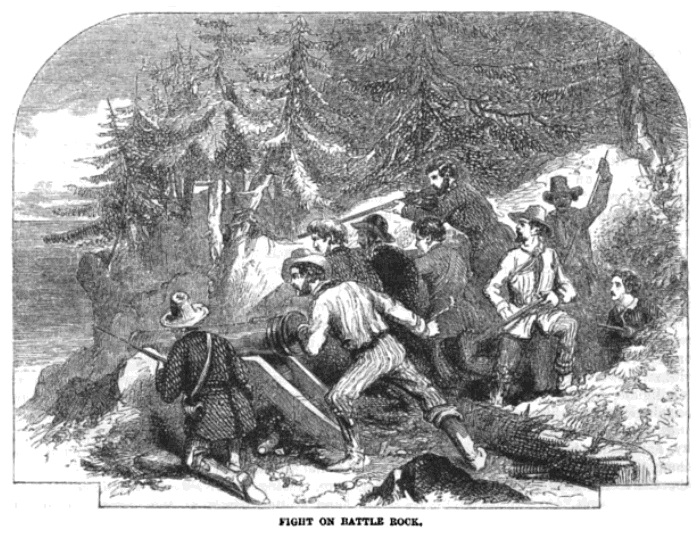

Battle Rock Note the contradictions in the eyewitnesses' accounts. Pay special attention to the Times-Picayune 1873 account. It's interesting to know that at the same instant those nine men were hunkered on the rock, eighty miles away Philip Kearny was murdering the inhabitants of the Rogue Valley and burning their villages and food. See also L. L. Williams' 1853 retelling of Cy Hedden's version and the 1880 Battle Rock account in the Marshfield Coast Mail. For Port Orford's subsequent early history, click here.  Battle Rock, 1920s

Advices from Oregon to May 24th have been received at San Francisco.

The propeller Sea Gull struck on a bar, in entering the Columbia River, injuring her screw. She had been hauled up, and was undergoing repairs. Democratic Banner, Bowling Green, Missouri, July 9, 1851, page 3 New Discoveries--A New City.

TICHENOR'S BAY.--This is a new harbor on our Pacific coast, discovered

by a former citizen of Newark, and by acclamation it has received his

name. It has also the melancholy interest of the murder of the first

nine white inhabitants who settled a promontory in

the bay, one of whom was probably our townsman, Cyrus Hedden, Jr.It is wonderful how the entire length of the Pacific coast within our lines is rapidly receiving settlements. The bay of San Francisco and the mouth of the Columbia River were the starting points, and good harbors are found where once the coast was considered iron bound, and from San Diego on the south to the Straits of Juan de Fuca on the north, we behold stretching along an almost continued line of new colonies. Their extent nearly equals our whole Atlantic coast, the Pacific coast running through 17 degrees of latitude, and the Atlantic through nearly 20. Below will be found an interesting letter to the California Courier about Tichenor's Bay: Port Orford,

Oregon, June 10th, 1851.

Editor of the California

Courier:The subject of exploration, and the announcement of new discoveries, are every day becoming more apparent upon the Pacific coast. Scarcely a year has now elapsed since the discovery of Humboldt and Trinidad bays were first made. The towns located upon these bays are interesting and flourishing, but are identified only as the trading points for the vast extent of mining district in the locality of the Klamath, and Umpqua and Rogue rivers, which are rapidly being made known to the public as being exceedingly rich, yet the extent of which is in a great measure unknown. It is a fact, however, well established, that gold abounds in considerable quantities at the celebrated "Gold Bluff," and extending up the Klamath and its tributaries, far into the interior. This fact, however, is nothing in comparison to the more recent discoveries of gold in the localities of the Umpqua and Rogue rivers, and the still more justly celebrated Shasta Valley, which is more richly impregnated with gold than any mines yet discovered in Oregon or California. The interior of the locality of these mines is about midway between Humboldt Bay and Portland, O.T., or including the towns in the vicinity of those above named, and about sixty or seventy miles from the coast, and, at the present time, some ten or twelve days are required to pack the provisions from the above-named places, at which they are purchased, to the mines, and a long, tedious and difficult trail at that. These things were well known to Captain Tichenor, the present commander of the steamer Sea Gull, who, something over one year since, while exploring the coast between the Umpqua and Klamath rivers, discovered a bay which he imagined formed a safe harbor for vessels nine-tenths of the year, and on a recent return trip of the Sea Gull from Columbia River, Captain Tichenor ventured into this bay for the purpose of making some further discoveries, and I am happy to say, to the entire satisfaction of both the captain and his passengers, and after viewing its beautiful and romantic scenery in the vicinity and making the necessary soundings, the passengers without a dissenting voice prefixed to the bay the name of our worthy captain, which is to be known hereafter as Tichenor Bay. The captain and several of the passengers landed on shore and explored the immediate vicinity, and according to the wishes and under the direction of Captain T., the necessary measures were adopted for the commencement of a city, to which was given the name of Port Orford. Messrs. J. M. Kirkpatrick, S. T. Slater, Jas. H. Hussey, Cyrus Hedden, R. H. Broadess, T. J. McKiron, G. W. Ridwert [Rideout?], P. D. Palmer and [John H.] Eagan were landed, with a sufficient amount of provisions, and the ample means for gardening, together with one cannon, a good quantity of small arms, munitions &c., which afford them sufficient equipments to resist any encroachment of the Indians residing in the vicinity. The pioneers immediately selected a high and commanding promontory, accessible only from two points, which they easily fortified, thereby giving them a position in which they can defend themselves, if necessary, against the attack of a thousand Indians, yet we anticipate no difficulty from them, and during our stay they appeared perfectly peaceable and friendly. Tichenor Bay (for such in fact we are now bound to call it) is located in Oregon Territory, ten miles north of Rogue River, and eight miles south from Cape Blanco, at a delightful point extending out into the sea, called Cape Orford, and in latitude 42 deg. 44 min. north, consequently it is 44 miles from the line of California. It has sufficient capacity to anchor the whole fleet of San Francisco harbor with as much safety as that of Valparaiso, it being similar in many respects to that place. It has a capacity four times greater than that of Trinidad, and is every way superior in the same ratio. The anchorage is good, and the depth of water ranges from three to twelve fathoms, and the harbor is entirely free from rocks underneath the surface of the water; consequently there is no obstruction in beating out of the bay against a headwind, which would be from the south and southwest, and the "southeasters," so much dreaded on this coast, could affect it but little. The surface of the soil in the vicinity of the bay is of a crescent form, and judging from the exuberant growth of wild clover, strawberries, and other vegetable matter now growing upon it, it must be a soil unsurpassed in productive qualities. There is in the vicinity, both north and south on the coast, some of the most magnificent prairies that we have yet had the pleasure of seeing, either in California or Oregon, and abound with a profusion of deer and elk. There is an excellent quality of redwood timber, sufficient for building purposes, within one mile from the bay. There are also quite a number of trees growing upon the site chosen for the new city, and the surface is beautifully decorated with flowers of every color, making it one of the most delightful and picturesque landscapes ever drawn by nature. Adieu,

J. F. C. [sic--James C.

Franklin]

Newark

Daily Advertiser, August 12, 1851, page 2

The Columbia, Capt.

LeRoy, arrived on Sunday in 56 hours from Astoria. She brings exciting

news relative to the difficulties with the Indians on Rogue River.

Several parties of whites have been attacked and a number of persons

robbed and killed. Nine men are yet missing, whose names are J.

Kirkpatrick, S. T. Slater, James H. Hussey, Cyrus Kidder, R. H.

Broadess, T. H. McKiron, T. W. Ridwort, P. D. Palmer and Sumner. These

persons were left by Capt. Tichenor at the mouth of the river on the

8th inst., on the last trip of the Sea

Gull.

J.

M. Kirkpatrick"Late and Important from Oregon," Sacramento Daily Union, July 1, 1851, page 2 PROBABLE MASSACRE.

The following account of

the probable destruction of a small party of

men who went from this place a short time since, by the Rogue River

Indians, was furnished by D. S. Roberts, purser of the steamship Columbia to the

editor of the Oregonian,

from which we copy:DEAR SIR:--The following account must prove of interest to your readers, and may serve, owing to its being the details of a sad transaction, so far as we can judge in consequence of the mystery yet surrounding it, to put the inhabitants of the Territory on their guard as to the nature and disposition of the Indians in the vicinity of Rogue River. Capt. Tichenor on his last downward voyage in the steamer Sea Gull had landed at a place which he named Port Orford, and which by reason of its being a better harbor than either Trinidad or Humboldt, and also from the nature of the land around, he judged to be a suitable place for establishing a settlement. With this view he left nine men, well armed and provisioned, under the command of Captain Kirkpatrick, and selected as a post for them the summit of a little island, from its nature almost inaccessible to an attack, there being but a narrow and steep path to it, along which two men could hardly advance abreast--and this, too, was raked by a four-pounder, which was left with the party and placed in position for that purpose. Cautioning them to deal carefully with the Indians, who at that time made their appearance in small numbers and were seemingly well disposed, he left there in the Sea Gull, promising to return by the 23rd of June, with further supplies and a larger number of men to survey and settle the place. After the arrival of the Sea Gull at San Francisco, it was found that she would not be able to return by the time appointed, and accordingly it was arranged between Capt. Tichenor and Capt. Knight, the agent of the Mail Steamship Company, that the Columbia should touch at Port Orford on her way up, and land him and two others who were with him, together with further supplies of provisions taken on board for that purpose. Having touched at Humboldt and Trinidad on our way up, we came in sight of Port Orford at 9 o'clock in the morning of the 23rd of June, that being the very day set by Capt. Tichenor for his return. At the distance of six or eight miles we could see through the glasses of the ship the smoke of a fire built at the base of the island spoken of, and from this we concluded that the men were all safe and waiting the arrival of the steamer. As we came up parallel with the shore and at a distance of somewhat more than a mile from it, we noticed three Indians running at full speed along the beach in a direction away from the island, and a canoe containing three more pulling with all speed in the same direction. This first caused us to suspect something wrong had happened, although we felt almost certain that the smoke we saw was rising from a fire kindled by the men as a sign of their presence. However, the brass six-pounder, which is used in announcing the arrival of the steamer, was fired to give notice to the men, as well as to see what effect the sound of it would produce on the Indians in the canoe, which was then about a mile distant. They all fell flat in the bottom of the canoe as if through fear, but the next moment they sprang up and pulled hurriedly for the shore, which they soon reached and hid themselves in the woods. In the meantime we were rapidly approaching the island, at which no signs of life presented themselves, except the fire before spoken of. We anchored about a mile off, and the boat containing Capt. LeRoy, Capt. Tichenor, Mr. Catherwood and six or eight others pulled for the island. We landed at the base of it, which was laid bare and in connection with the mainland, it being low tide, but no one was there to welcome us. We first noticed that a great quantity of pilot bread was scattered for several feet along the shore as though washed there by the tide; then we saw several books and broken carpenter's tools lying around still further up on the sand. We placed them in the boat, and then mounted to the top of the island; there we found nothing but signs of destruction, which seemed to tell plainly the fate of those who had been left. A great quantity of potatoes lay scattered about as if the Indians had left them not knowing their use, while fragments of other carpenter's tools together with pieces of chests strewed the ground, evidently broken to pieces for the sake of the iron contained in them. While looking about this summit which appeared to have been stockaded for defense, but within which were marks of a severe struggle, a memorandum book was found which gave some clue to what had taken place. What relates to the affair is in these words: "Camp Kirkpatrick:--We arrived at our post on the 8th of June. Our company numbered nine men. We made our post on a small island; it was accessible only at one point. The 9th the Indians commenced an attack at about ½ past 7 in the morning. The Indians numbered some 33. We first discharged our four-pounder; it made a sad havoc among them. Then we fought hand to hand; they then retreated to the hills leaving 18 or 20 dead on the field. We had three men wounded, one had an arrow in his breast, another one through his ear, myself had one through the neck. 10th. Today we have had no trouble. 11th. We are prepared to meet them; we expect to have a hard fight in a few hours. These Indians are perfect devils. Yesterday everything went off smooth; today the boys done one thing in which I did not agree, that was by leaving camp with only three men to protect the post. They were in great danger of the Indians getting between them and the camp, but by good luck they did not." The above account is supposed to have been written by Capt. Kirkpatrick. There is a further account in part like the other and word for word in many places, but containing the following new particulars; after speaking of letting off the four-pounder, it says: "In the meantime the rifles commenced playing among them; Hussey killed two with one ball. The fight lasted about three hours, when the Indians left for the hills. We are at this time making entrenchments; we expect them this night although we have just made a treaty with the chief. We cannot say how many are killed, for one of them ran half a mile with a bullet in him. Capt. Kirkpatrick is busy strengthening our post." There follows in another hand some Canadian French, also in pencil, which is impossible to decipher wholly, but which evidently alludes to the affair as these detached words show: "Le Capitaine Kirkpatrick--un sauvage--par dieu sacre!" ending with this direction, perhaps his mother's, "Madame Le Monge, Rue de Dauphin, Paris, La Belle France." We then came down from the top to the base of the island again, where we noticed that the sand was much trampled and that several large stones had been flung upon it, so as to cover a space of about five feet square. It struck us that someone was buried there, and accordingly the sailors forming the boat's crew, using oars as shovels, removed the stones and sand, and at the depth of a foot the dead body of an Indian was found, who had been shot through the head with a rifle ball. There being no other traces to guide us at that spot, Capt. Tichenor, with two others all armed (36 shooters), went up the hills spoken of in the journal to reconnoiter. No traces of Indians were seen, but a letter sheet filled on four sides was found, which gave a more detailed account of the affair, although unfortunately it breaks off in the most interesting part. It is as follows: "We landed this morning and took possession of a small island detached from the mainland by a narrow passage of about 100 yards in width. It is dry and easy of access at low tide. We took our provisions up and made our encampment on the top of the island. We entertained some fears of the Indians, who began to gather along the beach in considerable numbers, so we made preparations to defend our camp. We planted our four-pounder so as to rake the passage to the bottom of the hill, there being but one passage that a person could approach the top of the island by. It rained all day today, which rendered it very unpleasant. The Indians appeared friendly at first, and showed some disposition to trade with us; but when they saw the vessel depart, they grew saucy and ordered us off, and when they found that we would not go, they all vamoosed. We found it necessary to keep up a guard to watch their maneuvers. June 10. We were aroused from our slumbers this morning at an early hour by the guard, with the intelligence that the Indians were collecting on the beach. They came up from towards the mouth of Rogue River, and across the hills. There were about 40 of them on the ground at sunup; they appeared quite saucy. I noticed that they were all better armed than when here the day before. They struck up a fire about 100 yards from our camp; and held a kind of council of war, which consisted in counseling with each other, and frequently there would be from two to three of them dancing and whistling round at a furious rate, snapping their bowstrings at every turn they made. These maneuvers lasted about half an hour; during this time they were joined by several others. They waited a short time, when they were joined by 12 others who came up the coast in a large canoe. There were some few squaws with them, who started and ran off. The men then began to approach us. There were two or three of us went part of the way down the hill and motioned them to keep off, but they were bent for a fight. They came up threatening they would kill us. We then retired to the top of the hill, where we had our gun stationed. "They still followed us and wanted to break through into camp. One of them who appeared to be a leader among them seized hold of a gun belonging to one of our company and tried to wrest it from him; they--" Here the journal, which appears to have been regularly kept, beginning at Portland at the date of June 6th, suddenly ends; the remaining leaves having been without doubt scattered about by the Indians, being like the books regarded as worthless by them. Finding it useless to remain on shore any longer, we started for the steamer; but when about half a mile off we saw a person on shore dressed in the clothing of a white man, wearing a California hat, and having a rifle on his back. We instantly put back, supposing that it was one of the party who had chanced to survive, and had come down to the shore to be taken up by us. As soon, however, as we turned our boat towards the shore, he started for the woods. We fired a shot in that direction, and he fell on his face, just as the Indians in the canoe had done. He could not have been hit, for he was beyond the range of a rifle, and besides in a very few seconds he started up and reached the woods. The fact of his being dressed in the complete dress of a white man, together with his having a rifle, convinced us that the party must have been either wholly or partially destroyed. Capt. Tichenor, however, still has hopes of them, and thinks that having expended their ammunition, they have started for the mountains, intending to reach the white settlement of Oregon. If this is the case they have acted very foolishly and rashly for they have a post almost impregnable, either with or without ammunition; against such hostile Indians as those, their little band would not have the slightest chance of escape. It may be they have held a parley with the Indians and agreed to take a canoe and leave their territory, a proposition which the party would probably agree to, after having been harassed some days by continual fighting and watching. If so, however, they ought to have been at Trinidad at the time we touched there, for the distance is only 100 miles, and the winds and the currents, together with rowing, would take a canoe there in 24 hours. But the most probable supposition is that they have been entrapped into a treaty or truce with the Indians, and having been thrown off their guard, have been cut off. The Columbia, unless compelled by want of time (she being obliged to connect with the mail steamer of the 1st at San Francisco), will return on her way down, and a strong party will go on shore and remain some hours, when it is hoped that some other traces of the fate of the party may be obtained, or that at least some opportunity may offer for inflicting retribution on the said Indians concerned in the affair. The names of the parties so far as may be remembered are: Capt. Kirkpatrick, Messrs. Hussey, Slater, Hedden, Egan and four others. The Weekly Times, Portland, July 3, 1851, page 2 A copy of this letter, apparently revised by its author, was printed by the New York Tribune on August 7 (below). Note the revisions to distances. Local Matters.

We publish in another column today an interesting account [the account immediately below,

transcribed from the New York Tribune] of the

supposed massacre of nine men under Capt. Kirkpatrick, at Port Orford,

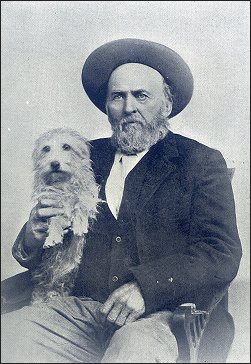

on Rogue River in Southern Oregon. Capt. Tichenor--who is a native of

this city--on his last trip up the coast, in the Sea Gull, had

landed at this place, and named it, and, with the view of forming a

settlement, on account of its appearing to him to be a better harbor

than Humboldt or Trinidad, left these men for supplies, promising to

return on the 23rd. Being unable to do so, he sent the supplies by the

steamer Columbia, which

arrived there on the 22nd, and found none of the men there, but

evidence, from fragments of diaries scattered about and trampling of

the ground, that the party had undoubtedly been murdered by the

savages, who are described as a ferocious tribe, with whom the

Oregonians are now fighting inland, Gov. Gaines and Gov. Lane both

being absent, heading expeditions against them.

There is a special interest here in this affair on account of a report being current that a former citizen of Newark, now in California, was among the massacred party, but we are glad to say that it cannot be true--although his last name is in one of the lists in the papers--as letters have been received from him dated the 1st of July, in San Francisco. A letter was also received here yesterday from a well-known former citizen of Newark--Mr. James S. Gamble--dated at San Francisco, on the afternoon of the 30th of June, announcing his intention of starting on the following Saturday with a party of 100 men, in the Sea Gull, for this very settlement, but he does not even mention the massacre, as he undoubtedly would if the individual referred to had been one of the victims, and 24 hours had then elapsed between the arrival of the Columbia and the date of his letter, a sufficient lapse of time for him to have known it, had it been the fact. Mr. G. speaks encouragingly of the prospects of the party, and we perceive by the papers that new discoveries of gold have lately been made on Rogue River, which yield remarkably well. Newark Daily Advertiser, August 8, 1851, page 2 Massacre of Capt.

Kirkpatrick's Company at Port Orford.

The purser of the steamship Columbia

gives the following account of a massacre which took

place on the Pacific Coast, north of Trinidad Bay:Capt. Tichenor, on his last downward voyage in the Sea Gull, had landed at a place named by him Port Orford, which, from the fact of its being a better harbor than either Trinidad or Humboldt, as well as owing to the nature of the land around, he judged to be a suitable place for establishing a settlement. With this view he left nine men, well armed and provisioned, under the command of Capt. Kirkpatrick, and selected as a post for them the summit of a little island, almost inaccessible to an attack, there being but a narrow and steep path to it, along which two men could not advance abreast, and this was raked by a four-pounder, left for this purpose and placed in position. Cautioning them to deal carefully with the Indians, who at that time made their appearance in small numbers and were seemingly well disposed, he left there in the Sea Gull, promising to return by the 23rd of June, with further supplies and a larger number of men to survey and settle the place. After the arrival of the Sea Gull at San Francisco, it was found that she would not be able to return by the time appointed, and accordingly it was arranged between Capt. Tichenor and Capt. Knight, the agent of the Mail Steamship Company, that the Columbia should touch at Port Orford on her way up, and land him and two others who were with him, together with further supply of provisions taken on board for that purpose. Having touched at Humboldt and Trinidad on our way up, we came in sight of Port Orford at 9 o'clock in the morning of the 22nd June, that being the very day set by Capt. Tichenor for his return. At the distance of eight miles we could see the smoke rising from the base of the little island, and from this we concluded that the party was all safe and waiting the arrival of the steamer. As soon as we came to the distance of about four miles from the island, we saw through the glasses three Indians running along the shore at full speed, in a direction away from the island, and a canoe containing three more, who were also pulling rapidly in the same direction. This first caused us to suspect that something wrong had happened, although we felt almost certain that the smoke we saw was rising from a fire kindled by the men. However, the brass six-pounder, which is used in announcing the arrival of the steamer, was fired to give notice to the men, as well as to see what effect the sound of it would produce on the Indians in the canoe, then about a mile distant. They all fell flat in the bottom of the canoe as if through fear, but in a moment they sprang up and pulling hurriedly to the shore, they soon hid themselves in the woods. In the meantime the steamer was rapidly nearing the island, at which no signs of life presented themselves, except the fire before spoken of. We anchored about a mile off, and our boat, containing Capt. LeRoy, Capt. Tichenor and six or eight others pulled for the island. We landed at the base of it, which was laid bare and connected with the mainland, it being low tide, but no one was there to welcome us. The first thing that attracted our notice was a great quantity of pilot bread, which had evidently been flung into the water, and had been broken and scattered along the beach for several yards, by the action of the waves, and on the sand, a little above, we found several broken carpenter's tools lying around. We then mounted the island, and on the top of it we found nothing but signs of destruction, which seemed to tell plainly the fate of those who had been left. All the potatoes which had been left with the party were scattered around, as if abandoned by the Indians, who were ignorant of their use, while the carpenter's tool chest, planes and other tools had been broken in pieces, evidently for the iron contained in them, for not the slightest particle of that or any other metal could be found. While looking about this summit, which appeared to have been stockaded for defense, but within which the ground was much trampled, as though a severe strife had taken place, a memorandum book was found, which gave some clue to what had occurred. What relates to the affair is in these words: "Camp

Kirkpatrick, June 8.

"We

arrived at our post on the

8th June--our company numbered nine men. We made our post on a

small island--it

was accessible only at one point."9th. The Indians commenced an attack at about half-past seven in the morning; the Indians numbered some thirty-eight. We first discharged our four-pounder; it made a sad havoc among them. Then we fought hand to hand; they then retreated to the hills leaving 18 or 20 dead on the field. We had three men wounded, one had an arrow in his breast, another, one through his ear, and I had one through my neck. "10th. Today we have had no trouble. "11th. We are prepared to meet them; we expect to have a hard fight in a few hours. These Indians are perfect devils. Yesterday everything went off smooth. Today the boys did one thing in which I did not agree--that is, by leaving camp with only three men to protect the post. They were in great danger of the Indians getting between them and the camp, but by good luck they did not." The above account is supposed to have been written by Capt. Kirkpatrick. There was a further account on another page, repeating the other generally, but containing the following new particulars. After speaking of letting off the four-pounder, it says: "In the meantime the rifles commenced playing among them. Hussey killed two with one ball. The fight lasted about three hours, when the Indians left for the hills. We are at this time making entrenchments; we expect them this night, although we have just made a treaty with the chief. We cannot say how many are killed, for one of them ran half a mile with a bullet in him. Capt. Kirkpatrick is busy strengthening our post." There follows, in another hand, some Canadian French, in pencil, which it is impossible to decipher, but evidently alluding to the skirmish, as these words show: "Le Capitaine Kirkpatrick * * * un sauvage * * * par dieu sacre!" Ending with this direction, probably that of the mother of the writer: "Madame Le Monge, Rue de Dauphin, Paris, La Belle France." We then came down to the foot of the island again, where we noticed that the sand had lately been trampled, and that several large stones had been flung upon a space of ground about five feet square. It struck us that someone was buried there, and accordingly the sailors forming the boat's crew, using their oars as shovels, removed the stones and sand, and at the depth of a foot the dead body of an Indian was found, who had been shot through the head with a rifle ball. There being no other traces to guide us at that spot, Capt. Tichenor, with two others, all armed with rifles (36 shooters), went up the hills spoken of in the journal to reconnoiter. No signs of Indians were seen, but a letter sheet filled on four sides was found, which gave a more detailed account of the matter, although unfortunately it breaks off in the most interesting part. It is as follows: "We landed this morning and took possession of a small island, detached from the mainland by a narrow passage of about 100 yards in width. It is dry and easy of access at low tide. We took our provisions up and made our encampment on the top of the island. We entertained some fears of the Indians, who began to gather along the beach in considerable numbers, so we made preparations to defend our camp. We planted our four-pounder so as to rake the passage to the bottom of the hill, there being but one passage that a person could approach the top of the island by. It rained all day today, which rendered it very unpleasant. The Indians appeared friendly at first, and showed some disposition to trade with us; but when they saw the vessel depart, they grew saucy and ordered us off, and when they found that we would not go, they all vamoosed. We found it necessary to keep up a guard to watch their maneuvers. "June 10. We were aroused from our slumbers this morning at an early hour by the guard, with the intelligence that the Indians were collecting on the beach. They came up from towards the mouth of Rogue River, and in across the hills. There were about forty of them on the ground at sunup; they appeared quite savage. I noticed, too, that they were all better armed than when here the day before. They struck up a fire about one hundred yards from our camp; and held a kind of council of war, which consisted in counseling with each other, and frequently there would be from two to three of them dancing and whirling round at a furious rate, snapping their bowstrings at every turn they made. "These maneuvers lasted about half an hour. During this time they were joined by several others. They waited a short time, when they were joined by twelve others, who came up the coast in a large canoe. There were some few squaws with them, who started and ran off. The men then began to approach us. There were two or three of us that went part of the way down the hill and motioned them to keep off, but they were bent for a fight. They came up, threatening they would kill us. We then retired to the top of the hill, where we had our gun stationed. They still followed us, and wanted to break through into the camp. One of them, who appeared to be a leader among them, seized hold of a gun belonging to one of our company and tried to wrest it from him; they--" Here the journal ends abruptly, having reached the bottom of the fourth sheet, and the rest could not be found--having probably been scattered about by the Indians, who regarded it as worthless. Finding it useless to remain on shore any longer, we started for the steamer, but when about half a mile from the shore we saw a person coming down to the water dressed in the clothing of a white man, wearing a California hat, and having a rifle on his shoulder. We instantly put back, supposing that it was one of the party who had survived, and had come down to the shore to be taken up by us. As soon, however, as we turned our boat toward him, he started for the woods. We fired a rifle ball in that direction, and he fell just as the Indians in the canoe had done, but he could not have been hit, for he was beyond the range of a rifle, and in a second or two he started up and reached the woods. The fact of his being dressed in the clothing of a white man, together with his having a rifle, convinced us that the party must have been either wholly or partially destroyed. The Columbia, unless compelled by want of time (she being obliged to connect with the mail steamer of the 1st at San Francisco), will stop on her way down, and a strong party will go on shore, when it is hoped that some further traces of the fate of the party may be obtained, or that at least some opportunity may offer for inflicting a severe punishment on the Indians concerned in their destruction. The names of the party left, as far as may be remembered are: Capt. Kirkpatrick, Messrs. Hussey, Slater, Hedden, Egan, Summers and three others. June 27.--The Columbia, having landed passengers and mails at Astoria, arrived today at Port Orford again. A strong party went on shore, but no Indians were seen, although they had been there since we left. The four-pounder was found partially buried in sand, having been without doubt flung over the side of the island by the Indians. About a quarter of a mile from the place where the last journal was found, and among the ruins of an old Indian ranch, a further journal was found, a part of which answers as a continuation of the unfinished one, though in a different hand. It is as follows: "When the council was ended, they drew their knives and sprung their bows and advanced to the foot of the hill and commenced coming toward us. In a moment they let go an immense number of arrows, and the fight began. They were six or seven times our number, and we let off our cannon among them, loaded with about thirty slugs. We fought nearly hand to hand for about twenty minutes, when the Indians broke and ran, leaving twelve or fourteen dead at the foot of the hill, and about double the number wounded. They fled to the high grass, about 200 yards distant, and continued to shoot their arrows until nearly sundown, when they left, leaving six more whom we had shot while they were on the hill. In a short time two of the chiefs gave us a visit, and we made them a little present of a couple of five-franc pieces, in which I made holes and put strings in and hung them around their necks--at which they seemed much satisfied--and went away again. I have seen a great many Indians in the States and crossing the plains, but I have never seen a more perfect set of savage devils than these Rogue River Indians. They will pick your pockets so quick that it would nearly throw a New York pickpocket in the shade, and will steal anything they can lay their hands on. They will stand and fight." The journal goes on, briefly stating that, during the 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th, they remained in their camp, receiving occasional visits from single Indians, expecting an attack. On the 16th they seem to have been occupied in exploring the country for some miles around, and the journal gives a very full and glowing description of it. The 17th was spent in like manner. 18th was spent in hunting. June 19th all stayed in camp, expecting an attack from the Indians. 20th very foggy; all in camp on the lookout for the steamer Sea Gull. Here the journal ends, and from the whole tone of it only one conclusion can be arrived at, and that is that between the 20th and 23rd they imprudently continued their exploring, and that the Indians, having been for some days concentrating their strength, had attacked them in the woods and cut them off to a man, and the fact that we saw the Indians on the 23rd, dressed in their clothing and having a rifle strengthens the supposition. I have further to add that the Oregonians are now fighting these same Indians further inland, and that Gov. Gaines and Gov. Lane are both absent, heading expeditions against them. Truly

yours,

New

York Daily Tribune, August

7, 1851, page 7. There

are three versions of this account transcribed on this page, containing

many variations, printed July 3, August 7 and August 9.D. S. ROBERTS. Two Weeks Later from Oregon.

The news from Oregon is almost wholly made up of Indian depredations

upon the settlers and those who wander through the wilds of the

Territory in search of places upon which to settle.

The following will be found of interest: From

the Alta California, July

1.

The steamship Columbia,

Captain

Le Roy, arrived yesterday morning from Astoria, Oregon, whence she

sailed on the 26th instant, at half past 2 o'clock p.m. The news

brought by this arrival is very interesting, but deeply distressing, as

it apprises us of the destruction of Captain Kirkpatrick and his party

of nine men, who had established themselves at a place named Port

Orford, in the vicinity of Rogue's River, in the lower portion of

Oregon. We are indebted to Mr. D. E. Roberts, the purser of the Columbia, for

an extremely interesting account of the melancholy affair, which will

be found subjoined. The Indians of Rogue's River have always been

warlike and hostile in their intercourse with the whites:

The Loss of Captain

Kirkpatrick's Party.

STEAMSHIP

COLUMBIA (at sea), June 24, 1851.

The following account may prove of interest to your readers, and, owing

to its containing the details of the sad affair, so far as we can judge

from the mystery yet surrounding it, may give some idea of the nature

and disposition of the Indians in the vicinity of Rogue's River.Capt. Tichenor, on his last voyage down in the Sea Gull, had at a place named by him Port Orford, which, from the fact of its being a better harbor than either Trinidad or Humboldt, as well as owing to the nature of the land around, he judged to be a suitable point for establishing a settlement. With this view, he left nine men, well armed and provisioned, under the command of Capt. Kirkpatrick, and selected as a post for them the summit of a little island, almost inaccessible to an attack, there being but a narrow and steep path to it, along which two men could not advance abreast, and this was raked by a four-pounder left for that purpose and placed in position. Cautioning them to deal carefully with the Indians, who at that time made their appearance in small numbers, apparently well disposed, he left them in the Sea Gull, promising to return by the 23rd of June, with further supplies and a larger number of men to survey and settle the place. After the arrival of the Sea Gull at San Francisco, it was found that she would not be able to return by the appointed time; and accordingly it was arranged between Captain Tichenor and Captain Knight, the agent of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, that the Columbia should touch at Port Orford on her way up, and land him and two others who were with him, together with the further supply of provisions taken on board for that purpose. Having touched at Humboldt and Trinidad on our way up, we came in sight of Port Orford at 9 o'clock on the morning of the 23rd--that being the very day set by Capt. Tichenor for his return. At the distance of eight miles we could see the smoke rising from the base of the little island; and from this we concluded that the party were all safe, and waiting the arrival of the steamer. As soon as we came within about four miles of the island, we saw, through the glass, three Indians running along shore at full speed, away from the island, and a canoe containing three more, who were also pulling rapidly in the same direction. The first caused us to expect that something wrong had happened, although we felt almost certain that the smoke we saw was rising from a fire kindled by the men. However, the brass six-pounder, which is used in announcing the arrival of the steamer, was fired, to give notice to the men, as well as to see what effect the sound of it would produce on the Indians in the canoe, then about a mile distant. They all fell flat in the bottom of the canoe, as if through fear, but in a moment they sprang up, and, pulling hurriedly to the shore, they soon hid themselves in the woods. In the meantime, the steamer was rapidly nearing the island, on which no sign of life presented itself except the fire before spoken of. We anchored about a mile off, and our boat, containing Capt. Le Roy, Capt. Tichenor, and six or eight others pulled for the island. We landed at the base of it, which was bare and connected with the mainland, it being low tide, but no one was there to welcome us. The first thing that attracted our notice was a great quantity of pilot bread, which had evidently been flung into the water, and had been broken and scattered along the beach for several yards by the action of the waves; and on the sand, a little above, we found several broken carpenter's tools lying around. We then mounted the island, and on the top of it found nothing but signs of destruction, which seemed to tell plainly the fate of those who had been left. All the potatoes which had been left with the party were scattered around as if abandoned by the Indians, who were ignorant of their use, while the carpenter's tool chest, planes, and other tools had been broken in pieces, evidently for the iron contained in them, for not the slightest particle of that or any other metal could be found. While looking about this summit, which appeared to have been stockaded for defense, but within which the ground was much trampled, as though a severe strife had taken place, a memorandum book was found which gave some clue to what had taken place. What relates to the affair is in these words: "Camp Kirkpatrick. We arrived at our post on the 8th of June; our company numbered nine men. We made our post on a small island--it was accessible only at one point. The 9th, the Indians commenced an attack at about half past seven o'clock in the morning. The Indians numbered some thirty-eight. We first discharged our four-pounder; it made sad havoc among them. Then we fought hand to hand. They then retreated to the hills, leaving eighteen or twenty dead on the field. We had three men wounded. One had an arrow through his breast; another, one through his ear; myself had one through my neck. 10th--Today we have had no trouble. 11th--We are prepared to meet them. We expect to have a hard fight with them in a few hours. These Indians are perfect devils. Yesterday everything went off smoothly. Today the boys did one thing in which I did not agree--that was leaving the camp with only three men to protect the post. They were in great danger of the Indians getting between them and the camp; but, by good luck, they did not." The above account was supposed to have been written by Captain Kirkpatrick. There was a further account on another page respecting the others generally, but containing the following new particulars. After speaking of letting off the four-pounder, it says: "In the meantime, the rifles commenced playing among them. Hussey killed two with one ball. The fight lasted about three hours, when the Indians left for the hills. We are at this time making entrenchments. We expect them this night, although we have just made a treaty with the chief. We cannot say how many we killed, for some of them ran half a mile after being shot. Captain Kirkpatrick is busy strengthening our post." Then follows in another hand some Canadian French which it is impossible to decipher, but evidently alluding to the skirmish, as these words show: "Le Capitaine Kirkpatrick--un sauvage--pardieu sacre!" ending with this direction [address], probably to the mother of the writer: "Madame Le Monge, rue de Dauphin, Paris, La Belle France." We then came down to the foot of the island again, where we noticed that the sand had lately been trampled, and that several large stones had been flung upon a space of ground five feet square. It struck us that someone was buried there, and accordingly the sailors forming the boat's crew, using their oars as shovels, removed the stones and sand, and at the depth of one foot the dead body of an Indian was found, who had been shot through the head with a rifle ball. There being no further traces to guide us at that spot, Captain Tichenor, with two others, all armed with rifles (36 shooters), went up the hills, spoken of in the journal, to reconnoiter. No signs of Indians were seen, but a letter sheet, filled on four sides, was found, which gave a more detailed account of the matter, although, unfortunately, it breaks off in the most interesting part. It is as follows: "We landed this morning and took possession of a small island, detached from the mainland by a narrow passage of about 100 [sic] yards in width. It is dry and easy of access at low tide. We took our provisions up, and made our encampment on top of the island. We entertained some fears of the Indians, who began to gather along the beach in considerable numbers; so we made preparations to defend our camp. We planted our four-pounder so as to rake the passage to the bottom of the hill, there being but one passage that a person could approach the top of the island by. It rained all day today, which rendered it very unpleasant. The Indians appeared friendly at first, and showed some disposition to trade with us; but when they saw the vessel depart, they grew saucy, and ordered us off; and when they found we would not go, they all vamoosed. We found it necessary to keep a guard to watch their maneuvers. "June 10.--We were aroused from our slumbers this morning at an early hour, by the guard, with the intelligence that the Indians were collecting on the beach. They came up from towards the mouth of Rogue's River, and in across the hills. There were about forty of them on the ground at sunup; they appeared quite saucy; I noticed, too, that they were all better armed than when here the day before. They struck up a fire about one hundred yards from our camp, and held a kind of council of war, which consisted in counseling with each other, and frequently there would be from two to three of them dancing and whirling round at a furious rate, snapping their bowstrings at every turn they made. "These maneuvers lasted for about half an hour. During this time they were joined by several others. They waited a short time, when they were joined by twelve others, who came up the coast in a large canoe. There were some few squaws with them, who started and ran off. They now began to approach us. There were two or three of us that went part of the way down the hill and motioned them to keep off, but they were bent for fight. They came up threatening they would kill us. We then retired to the top of the hill, where we had our gun stationed. They followed us, and wanted to break into the camp. One of them, who appeared to be a leader among them, seized hold of a gun belonging to one of our company, and tried to wrench it from him; they"---- Here the journal ends abruptly, having reached the bottom of the fourth sheet, and the rest could not be found, having probably been scattered about by the Indians, who regarded it as worthless. Finding it useless to remain on shore any longer, we started for the steamer; but when about half a mile from the shore we saw a person coming down to the water, dressed in the clothing of a white man, wearing a California hat, and having a rifle on his shoulder. We instantly put back, supposing it was one of the party who had survived, and had come down to the shore to be taken off by us. As soon, however, as we turned our boat towards him, he started for the woods. We fired a rifle ball in that direction, and he fell, just as the Indians in the canoe had done, but he could not have been hurt, for he was beyond the range of a rifle; and in a second or two he started up and reached the woods. The fact of his being dressed in the clothing of a white man, together with his having a rifle, convinced us that the party had been either wholly or partially destroyed. The names of the party left, as far as remembered, are Captain Kirkpatrick, Messrs. Hussey, Slater, Hedden, Egan, Summers, and three others. The Columbia, having landed passengers and mails at Astoria, arrived at Port Orford again June 27. A strong party went on shore, but no Indians were seen, although they had been there since we left. The four-pounder was found partly buried in the sand, having been, without doubt, flung over by the Indians. A quarter of a mile from the place where the last journal was found, and among the ruins of a small Indian rancho, a further journal was found, a part of which answers as a continuation of the unfinished one, though in a different hand. It is as follows: "When the council was ended, they drew their knives and sprung their bows, and advanced to the foot of the hill, and commenced coming towards us. In a moment they let go an immense number of arrows, and the fight began. They were six or seven times our number, and we let off our cannon among them, loaded with about thirty slugs. We fought for about twenty minutes, when the Indians broke and run, leaving twelve or fourteen dead at the foot of the hill, and about double that number wounded. They fled to the high grass, about two hundred yards distant, and continued to shoot their arrows until nearly sundown, when they left, leaving six more that we had shot while they were on the hill. In a short time two of the chiefs gave us a visit, and we made them a little present of a couple of five-franc pieces, which I made holes in and put strings in, and hung them around their necks, at which they seemed much satisfied, and went away again. I have seen a great many Indians in the States, and crossing the plains, but I have never seen a more perfect set of savage devils than these Rogue River Indians. They will pick your pockets so quick that it will nearly throw a New York pickpocket in the shade, and will steal anything they can lay their hands on. They will stand and fight." The journal then goes on briefly stating that during the 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, and 15th, they remained in their camp, receiving occasional visits from single Indians, and expecting an attack. On the 16th they seemed to have been occupied in exploring the country for some miles around, and the journal gives a very full and glowing description of it. The 17th was spent in like manner. The 18th was spent in hunting. "June 19.--All stayed in camp, expecting an attack from the Indians. 20th.--Very foggy; all in camp, on the lookout for the steamer Sea Gull." There the journal ends; and from the whole tone of it only one conclusion can be arrived at; and that is that, between the 20th and 22nd, they imprudently continued their exploring, and that the Indians, having been for some days concentrating their strength, had attacked them in the woods, and cut them off to a man; and the fact that we saw the Indian on the 23rd dressed in their clothing and having a rifle strengthens the supposition. I have further to add that the Oregonians are now fighting these same Indians further inland, and that Governor Gaines and Governor Lane are both absent, heading expeditions against them. [At the same moment the nine men were besieged on Battle Rock, Philip Kearny was attacking the natives in the Rogue Valley.] Washington Union, Washington, D.C., August 9, 1851, page 2 There are three versions of this account transcribed on this page, containing many variations, printed July 3, August 7 and August 9. Local Matters.

FURTHER FROM THE OREGON

MASSACRE.--We have been favored this

afternoon

with the following extract from a private letter from Capt. Wm.

Tichenor, received by the last California steamer, to his brother in

this city. We are further informed that Capt. T. has been for some

months past engaged in exploring the coast and country, with a view of

forming a settlement and taking advantage of the act of Congress

appropriating land to settlers, and that he had thoroughly performed

it. During one of his voyages he had discovered a new harbor, of

uncommon advantages, into which Rogue River empties, which he named

"Tichenor's Bay," and, inland, on exploration, found a bed of

anthracite coal of extraordinary richness within 50 yards of the bay.

We are also informed that the country around proved to be valuable,

both in agricultural capacity and gold mining.

It was this that induced him to leave the men on the island in the bay, who have probably fallen victims to their imprudence. Capt. T., as will be seen below, gives the melancholy information that a son of Mr. Cyrus Hedden, of this city, is without doubt one of the party murdered. This is not the individual referred to yesterday, although of the same name: "I am sorry to state to you that it is my belief that Cyrus Hedden is murdered by those savages, as he was of the party. I will make a thorough examination as I go up this time. All the Indians in that vicinity will now be exterminated immediately. I shall take a company of picked men, as I did before, but more of them. It is the finest climate, country and harbor I ever saw." Newark Daily Advertiser, August 9, 1851, page 2 More

Indian Outrages.

Capt. Tichenor, master of the steamer Sea Gull, on his

last trip down the coast, we learn from the Oregonian, landed

some nine men on a little island in the Rogue River country. Captain

Tichenor proceeded down the coast to California for the purpose of

increasing the number of his party, to procure provisions, etc.,

intending to return immediately and form a settlement here, which he

named Port Orford. The Capt. had set the time for returning on the 23rd

of June. The Sea Gull being

detained, Captain Tichenor boarded the Columbia and

returned to Port Orford at the expected time--the 23rd ult.

On nearing the point, no certain visible sign of the whites' safety could be discerned. Captain Le Roy, of the steamer Columbia, and Captain Tichenor, accompanied by six or eight other persons, went in search of the men. The party landed at the head of the island--no men were to be found; the pilot bread, potatoes and some of the carpenter's tools left in possession of the men were found strewed upon the ground. The conclusion by this time was irresistible that the men had been murdered by the Indians. In looking around, a memorandum book was found, from which they received some clue to what had taken place. What relates to the affair is in these words: "Camp Kirkpatrick:--We arrived at our post on the 8th of June. Our party numbered 9 men. We made our post on a small island; it was accessible only at one point. The 9th the Indians commenced an attack at about 7¼ in the morning. The Indians numbered some 33. We first discharged our four-pounder; it made a sad havoc among them. Then we fought hand to hand; they then retreated to the hills, leaving 18 or 20 dead on the field. We had three men wounded; one had an arrow in his breast, another one through his ear, myself had one through the neck. 10th. Today we have had no trouble. 11th. We are prepared to meet them; we expect to have a hard fight in a few hours. These Indians are perfect devils. Yesterday everything went off smooth; today the boys done one thing in which I did not agree--that was by leaving camp with only three men to protect the post. They were in great danger of the Indians getting between them and the camp, but by good luck they did not." The above account is supposed to have been written by Capt. Kirkpatrick. There is a further account in part like the other and word for word in many places, but containing the following new particulars: after speaking of letting off the 4-pounder, it says: "In the meantime the rifles commenced playing among them; Hussey killed two with one ball. The fight lasted about three hours, when the Indians left for the hills. We are at this time making entrenchments; we expect them this night although we have just made a treaty with the chief. We cannot say how many are killed, for one of them ran half a mile with a bullet in him. Capt. Kirkpatrick is busy strengthening our post." We then came down from the top to the base of the island again, where we noticed that the sand was much trampled and that several large stones had been flung upon it, so as to cover a space of about five feet square. It struck us that someone was buried there, and accordingly the sailors forming the boat's crew, using their oars as shovels, removed the stones and sand, and at the depth of a foot the dead body of an Indian was found, who had been shot through the head with a rifle ball. There being no further traces to guide us at that spot, Capt. Tichenor, with two others, all armed with rifles (36 shooters), went up the hills spoken of in the journal to reconnoiter. No traces of Indians were seen, but a letter sheet about filled on four sides was found, which gave a more detailed account of the affair, although unfortunately it breaks off in the most interesting part. It is as follows: "We landed this morning and took possession of a small island detached from the mainland by a narrow passage of about 100 yards in width. It is dry and easy of access at low tide. We took our provisions up and made our encampment on the top of the island. We entertained some fears of the Indians, who began to gather along the beach in considerable numbers, so we made preparations to defend our camp. We planted our four-pounder so as to rake the passage to the bottom of the hill, there being but one passage that a person could approach the top of the island by. It rained all day today, which rendered it very unpleasant. The Indians appeared friendly at first, and showed some disposition to trade with us; but when they saw the vessel depart, they grew saucy and ordered us off, and when they found that we would not go, they all vamoosed. We found it necessary to keep up a guard to watch their maneuvers. "June 10. We were aroused from our slumbers this morning at an early hour by the guard, with the intelligence that the Indians were collecting on the beach. They came up from towards the mouth of Rogue River, and across the hills. There were about 40 of them on the ground at sunup; they appeared quite saucy. I noticed that they were all better armed than when here the day before. They struck up a fire about 100 yards from our camp and held a kind of council of war, which consisted in counseling with each other, and frequently there would be from two to three of them dancing and whistling round at a furious rate, snapping their bowstrings at every turn they made. These maneuvers lasted about half an hour; during this time they were joined by several others. They waited a short time, when they were joined by 12 others who came up the coast in a large canoe. There were some few squaws with them, who started and ran off. The men then began to approach us. There were two or three of us went part of the way down the hill and motioned them to keep off, but they were bent for a fight. They came up threatening they would kill us. We then retired to the top of the hill, where we had our gun stationed. "They still followed us and wanted to break through into camp. One of them who appeared to be a leader among them seized hold of a gun belonging to one of our company and tried to wrest it from him; they--" Here the journal, which appears to have been regularly kept--beginning at Portland at the date of June 6th, suddenly ends. The party of nine, supposed to have been murdered, are from Oregon, most of them from about Portland. Oregon Spectator, Oregon City, July 3, 1851, page 2 There are three versions of this account transcribed on this page, containing many variations, printed July 3, August 7 and August 9. (Correspondence

of the Statesman.)

P.M.S.S. Columbia, June 25,

1851.

Editor of the Statesman:

We have just touched at Port Orford with the view of leaving two surveyors who came prepared to lay out a new town at that place, but to our great surprise, the nine men left there by the steamer Sea Gull on her return from the Columbia River were missing; and from the appearance of the Indians, who immediately fled on our approach, we are forced to believe that all is not right. We found upon the ground an imperfect memorandum of an attack, in which some forty Indians were engaged in the contest, and some eighteen paid the forfeit, and three of the men were wounded, and whether mortally or not is impossible to determine. The memorandum also states that they expect a severe attack in a short time, the Indians having retreated after the first engagement. We also found a sheet of paper containing a journal of one of the individuals from the time he left Portland up to the time of the attack, in which he describes the war dance, and some other preliminaries prior to the engagement. We found no dead bodies upon the ground, with the exception of one Indian, who was buried in the sand nearby, yet the Indians whom we saw making their escape as we approached, seemed to be dressed in apparel not in accordance with their customs--yet proving almost beyond a doubt the certainty of a crime which they had perpetrated. The tools and provisions belonging to the pioneers were missing, with very few exceptions, in which articles were destroyed upon the ground. The first efforts, therefore, to commence a settlement have proved unsuccessful, but it will soon be renewed with much more effectual means, and in a manner too that will not admit of a single doubt as to its completion. The men who are engaged in this enterprise will not falter nor look back. They are men who are determined, and will certainly persevere in an undertaking so laudable, and one so well calculated to promote the commercial interests of the Pacific Coast. Yours, &c. J.C.F. Oregon Statesman, Oregon City, July 4, 1851, page 2 "J.C.F." is James C. Franklin. PORT ORFORD.--This new city which is being laid out on Tichenor Bay, in Oregon, is destined to become a place of much importance. Its location is about midway between Humboldt Bay and the mouth of Columbia River, and being much the nearest point to the mines of Shasta Valley, and to Umpqua and Rogues' rivers, with every facility for making a good trail, it will become the depot on the coast for those mining regions. The settlers there have sent down here to make all necessary purchases and supplies for substantial and permanent improvements with a view to settlement. The agricultural qualities of the surrounding country are unsurpassed, and in that point of view is most valuable. We shall expect to have regular correspondence from Port Orford, giving an account of the progress of improvements there, as the steamer Sea Gull will run in regularly on her trips to and from Oregon. It is intended to open a trail to the mining regions from that place immediately. [Cal. Cour. New York Daily Tribune, July 19, 1851, page 7 STEAMER SEA GULL.--This splendid steamer arrived at our levee on Monday morning. She, however, brought no later dates than we received by the Columbia; having sailed on the same day, stopping at Humboldt, Trinidad, Port Orford, &c. The Sea Gull remained at Port Orford four days. She landed sixty-four men with a large amount of stores, and implements of defense from the Indians, and agriculture, oxen, horses, &c. There appears, therefore, to be a determination on the part of Capt. Tichenor and others to possess themselves of this important point, which is said to possess advantages second to no place between the mouth of the Columbia River and San Francisco. The Sea Gull is to run hereafter as a regular steam packet between this place and San Francisco. Oregonian, Portland, July 26, 1851, page 2 Port Orford Correspondence.

The annexed interesting letter from Port

Orford, Oregon, is from the pen ol a former resident of this city,

whose attention, with that of others, has been directed to this new

point of attraction. He has promised to keep us informed of all matters

of interest in that section, which, from present indications, is likely

to become a position of considerable importance. His statements may be

relied upon with the utmost fidelity. It will be recollected that it

was at that place where Capt. Fitzpatrick and party were so nearly

sacrificed by the Indians, and as the present occupants of the place

are an equally adventurous band of pioneers, it is not at all unlikely

that their explorations in those wilds will prove to be of a character

well worthy of record. We commend the letter to perusal:PORT ORFORD,

O.T., July 26, 1851.

Messrs.

Editors:--I deem it necessary, in the commencement of my

correspondence, to inform the reader where Port Orford is located, and

then the subject contained in the correspondence will be much more

interesting, not only to the citizens of California, but more

particularly those of the Atlantic States; for when an individual reads

of a place in a distant part of the dominion in which he resides, he is

anxious to know the identical place where it is located; so also is it

the case with a person who resides in a foreign country.This place is easily identified, and by a chart of the Pacific coast Cape Blanco can easily be ascertained; then follow the coast southward until you reach latitude 42° 42-30", and by so doing the very identical point at which Point Orford is located will be determined. It is beautifully situated upon Tichenor Bay, and has a commanding view of the harbor, and the Pacific, far to the southward. The western view is obstructed by a high range of woody land, which not only intercepts the view, but the cold and unpleasant breezes from the west and northwest, which prevail during the summer season. The bay is considered by seamen a safe place of anchorage for vessels at least nine months of the year, and the remainder equally as sale as that of Valparaiso. The harbor is much larger than the first appearance would represent it, and by a recent survey it is ascertained that it contains an area of between five and six square miles; therefore it is sufficient to anchor the whole of the fleet now lying in the harbor of San Francisco. The only gales that could be considered dangerous would be from the south and southwest; and during a storm from either of these points there would be no difficulty in beating out of the bay, as there is sufficient capacity, and no rocks underneath the surface of the water that could be considered an impediment to a vessel's progress; consequently, there would be no obstructions arising from anything of that character. On the east and south sides of the harbor there is a high ridge of land, forming a branch of the Coast Range. This would prove an ample protection against the southeast winds which prevail during the winter season. The harbor can easily be identified in approaching it from the sea by a high, round mountain on the south, and a high, rocky point extending out on the north. It will be remembered by the readers of the Alta that some time since an account was published concerning the supposed massacre of nine men, who were left here in June last by the steamer Sea Gull, for the purpose of commencing a permanent settlement. This statement we are now prepared to amend in a great measure, and strong hopes are now entertained of their safety, and we have no doubt but that the steamer Sea Gull will bring tidings of their safe arrival at Portland. On the day of our arrival here, with our present expedition, another letter w»s found, written by Capt. Kirkpatrick himself, saying that they considered their case hopeless, and that they had resolved upon leaving their position that evening, and make their escape to the settlements in Oregon. The soil is exceedingly fertile in the vicinity of the bay. and beautifully located, and adorned with wild flowers of every form and color. Wild berries, of several different varieties, are growing abundantly; among them is one resembling very much the whortleberry of the Atlantic States, which is rapidly becoming a great favorite among the present dwellers of Port Orford. In the immediate vicinity of the bay there is a great variety of timber growing, among which there are some of the most beautiful specimens of forest grandeur that the eye ever beheld, and 1 will venture to say that no country can produce a more available article for building purposes. It is straight, uniform, and easily manufactured, and not unfrequeutiy have I noticed trees, free from limbs, at a distance from the surface of the soil upwards not less than one hundred and fifty feet, and measuring from six to eight feet in diameter. Having given a short description of the place, its locality, and some of the available interest connected with it, I will now proceed with the more interesting portion of my communication. I have just been interrupted by the arrival of the Sea Gull from Oregon, bringing the intelligence of the safety of the pioneers above spoken of, and I also learn that the Columbia has taken papers to San Francisco, containing the news of their arrival at Portland. The supposed massacre of the company here spoken of was the cause of the organization of the present expedition, which numbers sixty-five men, including projectors of the enterprise, their representatives, and the volunteers. Immediately on our arrival we selected a position easily fortified, and as soon as our stores. tents, &c., were secured, commenced the erection of two forts on commanding points, and at the same time secured the exposed avenues leading to [the] position with palisades. Our fortifications are now nearly completed, and we now consider ourselves ready for an attack by the Indians at any hour, yet we have had no reason to anticipate any such unpleasant transaction, for such, in fact, it would be to the Indians if they should commence hostilities. Our appointments are all complete, in the way of arms and ammunition, and in our present position we can resist successfully the attack of the combined force of all the Indians in the vicinity, particularly with their present arms of offense, namely, bows and arrows. The Indians have frequently been in camp, and exhibited every sign of peace and submission; yet we place but little reliance in their manifestations of friendship, but, on the contrary, we are at all times prepared to meet them. I have but one moment more to write, and I will occupy that in giving an account of the discovery of gold in the vicinity of this place, but in what quantity I am unable to say: yet we anticipate giving some good report in a future communication of the gold in this region. It is acrertained that gold in considerable quantities has been found within twenty-five miles of this place, and considerable excitement prevails in our camp concerning the diggings here spoken of. They were discovered by our own company, and by men in whom the utmost reliance can be placed; and a large number of the present population of this place will repair thither as soon as mining implements can be obtained from San Francisco. Adieu. CLINTON.

Daily

Alta California, San Francisco, August 1, 1851, page

2Oregon and California.

Very recent dates were received by the Prometheus, from

the Rev. Mr. Roberts, of this city. The following extract of one of his

letters will be perused with general interest.

"San

Francisco, July 30th, 1851.

"On Friday, the 18th inst., I left my family in usual health at Salem,

and spending the Sabbath at Oregon City, embarked on board the Sea Gull, at

Portland, the following Wednesday, bound for this place. We arrived in

the harbor last night, after dark, with no accident save the carrying

away of our main topmast, smoke pipe &c., by running afoul of

the Columbia mail

steamer, which was anchored directly in our road. Nobody was hurt on

either vessel, and the damage can easily be repaired. I have seldom

seen the hand of God more manifest than on this short voyage."The season has arrived for heavy weather all along the coast, and it is often difficult to see two ships' lengths through the fog. We are desired to stop at three places--Port Orford, Trinidad and Humboldt. The first of these places is an open roadstead, well protected except on the west and south, about ten miles below Cape Blanco, and nearly twenty north of the mouth of Rogue River. We approached the place on Saturday evening, but a fearful reef of rocks, extending from Cape Blanco, some eight miles into the Pacific, made our approach in the fog perilous. After groping about in the darkness until night, we stood out to sea again. Just at daylight, the fog lifted a few moments, and although it shut in thick, shortly after[wards] we reached the anchoring ground without damage. Several times we were within fifty feet of the rocks, and ascertained, when the fog lifted, at noon, that we had been within thirty yards of the shore, without the least damage whatever. A little over a month ago, nine men were left at this place to explore the adjacent country for coal and gold. They were attacked by the Indians, and after several days' fighting, during which time a number of Indians were killed, and two of the company wounded, they found their ammunition nearly gone, and made their way to the Willamette Valley, overland. "A reinforcement of seventy-five persons had arrived, and a kind of stockade fort was constructed, for protection, and arrangements are in progress to dig coal and gold, and sell town lots. "As we proceeded down the coast, little columns of smoke were to be seen rising at suitable distances far in advance of us, intended as signals to telegraph the approach of hostile enemies. The condition of these Rogue River Indians is deplorable. There exists a deadly feud between them and the whites, and as their land has gold in it, and must be explored, contest is inevitable. Not long since, Genl. Lane made a treaty with them. That treaty was broken by the whites. Gov. Gaines is now in that country, and the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Dr. Dart, will shortly proceed there to settle the difficulty. The weather continuing thick and hazy, we were unable to get into Trinidad or Humboldt, and after several ineffectual attempts to do so made the best of our way to Point Reyes, off the harbor of San Francisco. On ascertaining our true position on Tuesday evening, we were some forty miles to the westward of our course. This, as we had seen the land at Humboldt, created some alarm, and on examination a hatchet was found in the binnacle attracting the needle from its true position. Had the attraction been eastward instead of westward, such was the state of the weather, shipwreck was inevitable. Thanks be to God for his goodness! "On Wednesday morning we slowly made our way to the wharf, amid forests of masts and shipping, where, four and a half years ago, the approach of a single vessel was an important event. The two fire which raged so fearfully in this city have not altered the face of things so materially as I had expected. Quite a portion of it is rebuilt, and although business is said to be dull just now, there are unmistakable evidences of greatness about San Francisco." It will be understood that Mr. Roberts' visit to California was an official one required by his office of Missionary Superintendent. Rev. Mr. Owen, Presiding Elder of California, would return with him to the conference to be held in Oregon the present month. Newark Daily Advertiser, September 12, 1851, page 2 All Safe!

THE GALLANT

NINE.--We were not a little gratified last evening to learn of the safe

arrival in the settlements of the nine persons supposed to have been

murdered by the Rogue River Indians, who had been left at Port Orford

by Captain Tichenor, an account of which we gave in our last paper. A

gentleman who traveled in company with one of the nine--the only one

who has reached this part of the valley--informed us that the gallant

little party stationed at Port Orford maintained their ground manfully,

killing, in their encounter with the Indians, some 20 of their number.

Seven are said to have been killed by a single fire of the 4-pounder.

They are said to have kept possession of their camp up to the day

Captain Tichenor had set for returning, but thinking that he might

possibly be detained longer than he expected, and having only about

nine rounds each in their "lockers," they concluded they had little

enough to take them through the forests to the settlements. They

accordingly set out, the Indians keeping a close manage

on them all the while. They, however, "out-generaled" the Indians, and

all of them succeeded in gaining the settlements in safety. They think

the Indians very large in size, and a desperate set of fellows, and in

a perfect state of nudity. The whites took to the thickets of briars

and thorns, the Indians, sparing their garments, gave up

the chase; by this means, doubtless, they saved their lives.

Oregon Spectator, Oregon City, July 10, 1851, page 3 (Correspondence

of the Statesman.)

Portland, O.T., July

10, 1851.

Editor of the Oregon Statesman: